Krzyzsztof Kieslowski, BLIND CHANCE/PRZPADEK, 1981, (122 Min.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{ Inspirations }

{ inspirations } BraBraammS Stoktookoker’err ssD Dracrraa ulal , dirir.r. F.F F.F CCooppola TThTheh NiN nththh GaG tee, dir.ir RR.. Poolaańskiskkki © Agencja MJS © Agencja MJS In his career, Wojciech Kilar strictly debuting at the ‘Warsaw Autumn’ festival. piece”2. In another interview he bluntly de- observes two basic rules: firstly – He was keenly interested in all theoretical as- scribed the problem with a comparison: “An autonomous music for the concert hall is pects of film music. If the film (and of course autonomous composition is a house, and the in every respect more important than film the director) allowed it, Kilar eagerly experi- composer is the architect. In film, the director music, and secondly – silly movies that do mented with the music, with various ways of is the architect, and I’m just the decorator”3. not convey any deeper content are not juxtaposing it with the image and with the Despite this dependency, and the prob- worth writing music for; that time should function of music within the context of the lem of ‘ragged’ form, Wojciech Kilar has man- be spent writing concert music. Despite, film (K. Kutz Nikt nie woła, 1960, Milczenie, aged over the years to create countless mas- and because of this, Kilar has written music 1963, K. Zanussi Struktura kryształu, 1969). terpieces of film music, drawing on a wide for so many outstanding art films, which He quickly established himself as a composer variety of conventions, styles and techniques have passed into the history of Polish and who ‘felt’ the image and was able to illustrate associated with chamber and orchestral mu- international cinema. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

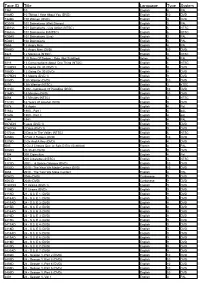

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Download Download

Polish Feature Film after 1989 By Tadeusz Miczka Spring 2008 Issue of KINEMA CINEMA IN THE LABYRINTH OF FREEDOM: POLISH FEATURE FILM AFTER 1989 “Freedom does not exist. We should aim towards it but the hope that we will be free is ridiculous.” Krzysztof Kieślowski1 This essay is the continuation of my previous deliberations on the evolution of the Polish feature film during socialist realism, which summarized its output and pondered its future after the victory of the Solidarity movement. In the paper “Cinema Under Political Pressure…” (1993), I wrote inter alia: “Those serving the Tenth Muse did not notice that martial law was over; they failed to record on film the takeover of the government by the political opposition in Poland. […] In the new political situation, the society has been trying to create a true democratic order; most of the filmmakers’ strategies appeared to be useless. Incipit vita nova! Will the filmmakers know how to use the freedom of speech now? It is still too early toanswer this question clearly, but undoubtedly there are several dangers which they face.”2 Since then, a dozen years have passed and over four hundred new feature films have appeared on Polish cinema screens, it isnow possible to write a sequel to these reflections. First of all it should be noted that a main feature of Polish cinema has always been its reluctance towards genre purity and display of the filmmaker’s individuality. That is what I addressed in my earlier article by pointing out the “authorial strategies.” It is still possible to do it right now – by treating the authorial strategy as a research construct to be understood quite widely: both as the “sphere of the director” or the subjective choice of “authorial role,”3 a kind of social strategy or social contract.4 Closest to my approach is Tadeusz Lubelski who claims: “[…] The practical application of authorial strategies must be related to the range of social roles functioning in the culture of a given country and time. -

Richard Haag Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ RICHARD HAAG ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Charles Anderson Lucia Pirzio-Biroli/ Michele Marquardi Luca Maria Francesco Fabris Falken Forshaw Gary R. Hilderbrand Jeffrey Hou Linda Jewell Grant Jones Douglas Kelbaugh Reuben Rainey Nancy D. Rottle Allan W. Shearer Peter Steinbrueck Michael Van Valkenburgh Thaisa Way © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Reflections of Richard Haag by Charles Anderson May 2014 I first worked with Rich in the 1990's. I heard a ton of amazing stories during that time and we worked on several great projects but he didn't see the need for me to use a computer. That was the reason I left his office. Years later he invited me to work with him on the 2008 Beijing Olympic competition. In the design charrettes he and I did numerous drawings but I did much of my work on a tablet computer. In consequent years we met for lunch and I showed him my projects on an iPad. For the first time I saw a glint in his eye towards that profane technology. I arranged for an iPad to arrive in his office on Christmas Eve in 2012. Cheryl, his wife, made sure Rich was in the office that day to receive it. His name was engraved on it along with the quote, "The cosmos is an experiment", a phrase he authored while I worked for him. He called © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. -

By Stanislaw Mucha

BY HOPE STANISLAW MUCHA HOPE SYNOPSIS HOPE BY STANISLAW MUCHA When a deeply moral and well-respected art historian steals an invaluable painting from a church, righteous and fanatic Francis records the crime on video to blackmail the perpetrator. Much to the thief’s bafflement, the young man is not interested in money but demands that the piece of art be returned to its original place. The borders between idealism and madness blur when it is revealed that Francis’ brother is in jail and his girlfriend has to tolerate Francis’ bizarre self-afflicted tests of courage … STANISLAW MUCHA DIRECTOR Born in 1970 in Nowy Targ, Poland, Stanislaw Mucha studied acting at the Federal Theater Academy “Ludwik Solski” in Krakow´ . After initial successes as an actor, Mucha left Poland to study directing at the The Film & Television Academy (HFF) “Konrad Wolf” in Potsdam-Babelsberg. He became well-known for his quirky documentary ABSOLUT WARHOLA (2001) tracing the origins of the US pop artist Andy Warhol to Poland, Slovakia and the Ukraine. HOPE is Mucha’s first feature film. DIRECTOR’S COMMENTS CAST DIRECTOR’S HOPE Franciszek/Francis HOPE is the story of extortion. An acclaimed art historian and moral authority steals a RAFAL FUDALEJ precious painting from a church… and is caught by a young fanatical do-gooder. Klara/Clare KAMILLA BAAR Hope. You know: “the mother of the stupid”, “hope springs eternal”, etc. I think that Benedykt/Benedict hope is an indispensable element of life. In every life; in my life too. While observing WOJCIECH PSZONIAK reality I feel as if there is no hope, as if it should be invented as fast as you can. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

El Valor Expresivo Del Color En El Cine De Kieslowski E Idziak

ISSN 2173-5123 El valor expresivo del color en el cine de Kieslowski e Idziak The Expressive Value of Color in the Cinema of Kieslowski and Idziak Iñaki LAZKANO ARRILLAGA Universidad del País Vasco [email protected] Recibido: 22 de octubre de 2013 Aceptado: 13 de marzo de 2014 Resumen La inmensa mayoría de las películas otorgan una función meramente formal al color. Aún así, los cineastas y teóricos más inquietos han reivindicado siempre el valor expresivo del color en el cine, puesto que consideran que la expresión cromática debe tener un fiel reflejo en el contenido del filme. La obra conjunta de Krzysztof Kieslowski y Slawomir Idziak, su director de fotografía predilecto, es un claro exponente de dicha corriente. No solo porque el tándem polaco dota de significado al color y contribuye con ello a revelar el mundo interior de los protagonistas de sus películas, sino, sobre todo, por la diversidad y originalidad de su estrategia cromática. Palabras clave Kieslowski, Idziak, color, memoria, esperanza. Abstract The immense majority of films give a merely formal function to color. Even so, the most enterprising filmmakers and theoreticians have always defended the expressive value of color in cinema, as they consider that chromatic expression should find a faithful reflection in the film’s content. The joint work of Krzysztof Kieslowski and Slawomir Idziak, his favourite director of photography, is a clear example of this current. Not only because the Polish duo endows color with meaning and contributes in this way to revealing the inner word of their films’ protagonists, but, above all, because of the diversity and originality of their chromatic strategy. -

Henryk Górecki's Spiritual Awakening and Its Socio

DARKNESS AND LIGHT: HENRYK GÓRECKI’S SPIRITUAL AWAKENING AND ITS SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT By CHRISTOPHER W. CARY A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Christopher W. Cary ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Christopher Caes, who provided me with a greater understanding of Polish people and their experiences. He made the topic of Poland’s social, political, and cultural history come alive. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Paul Richards and Dr. Arthur Jennings for their scholarly ideas, critical assessments, and kindness. I would like to thank my family for their enduring support. Most importantly, this paper would not have been possible without Dr. David Kushner, my mentor, friend, and committee chair. I thank him for his confidence, guidance, insights, and patience. He was an inspiration for me every step of the way. Finally, I would like to thank Dilek, my light in all moments of darkness. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Study.....................................................................................................1 -

ASO Program Notes

ASO Program Notes Orawa Wojciech Kilar (1932 - 2013) While Chopin is usually the first name to come to mind when speaking of Polish composers, there are a number of contemporary Polish figures who have distinguished themselves by incorporating Poland’s indigenous culture and landscape into their music. One of these is Wojciech Kilar, now recognized as Poland’s leading composer of symphony, oratorio and chamber music, as well as numerous sound tracks. He was trained in Krakow, then in Paris, studying under some of the greatest modern tutors of the 20th century and perfecting and adopting his distinctive neo-classical style. He performed regularly in concert halls and also accepted a number of commissions from film directors. Commissions included The Truman Show, Dracula, Portrait of A Lady, and The Pianist, among many others. After a period of particularly avant-garde productions, he settled into a strongly nationalistic style, showing elements of his country’s folk and religious music. His composition Orawa , completed in 1986, takes it’s title from the Carpathian region of the Polish-Slovak border. It also refers to mountainous terrain and grass-covered mountain pastures with rivers running through. It is the final work in Kilar’s “Tatra Mountain works” for string orchestra and has been suggested to depict the potent forces of nature and an exuberant folk festival at harvest time. Orawa is characterized by use of repeated figures played off against one another, with its texture varying in dynamics and rhythms for dramatic effect. It is the most popular of Kilar’s works, and has lent itself to a variety of arrangements, including, at various times, for string quartet, for twelve saxophones, accordion trio and eight cellos! In an interview in Krakow in 1997, Kilar said of his most famous work, “Orawa is the only piece in which I wouldn’t change a single note, though I have looked at it many times… What is achieved in it is what I strive for - to be the best possible Kilar.” Beryl McHenry .