Lucio A. Carbone Fernando Sor and the Panormos: an Overview of the Development of the Guitar in the 19Th Century Introduction Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Mark Hilliard Wilson St

X ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL X SEATTLE X 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 X 6:30 PM X MUSICAL PRAYER mark hilliard wilson St. James Cathedral Guitarist “Méditation” from Thaïs Jules Massenet 1842–1912 Etude No. 10 from 12 Etudes, Op. 6 Fernando Sor c. 1778–1839 Ave Maria Franz Schubert 1797–1828 Simple Gifts Joseph Brackett 1797–1882 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750 Gymnopédie No. 1 from Trois Gymnopédies Erik Satie 1866–1925 Nigbati Iya Mi Ba Reriin Taiwo Adegoke “When my mother laughs” birth year unknown Theme from second movement ofNew World Symphony Antonín Dvořák 1841–1904 Prelude No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846 J. S. Bach Woven World Andrew York b. 1958 Classical guitarist Mark Hilliard Wilson curates programs that explore the experiences of the heart through the ages, hoping to share some insight and reflection on our common humanity. He brings joy and technical finesse to the listener while integrating music from diverse backgrounds and different ages with a compelling story and a wry sense of humor. Performing regularly at festivals and concert series, Wilson has distinguished himself as a unique voice with programs that feature his own transcriptions of both the well-known and the obscure. Wilson’s compositions for the guitar have been appearing on stages throughout the Northwest US and Canada for over 15 years. He works in is the relatively unexplored genre of an ensemble of multiple guitars as the conductor, composer, arranger, and music director to the Guitar Orchestra of Seattle. Wilson has taught at Whatcom Community College and Bellevue College. -

Soundboardindexnames.Txt

SoundboardIndexNames.txt Soundboard Index - List of names 03-20-2018 15:59:13 Version v3.0.45 Provided by Jan de Kloe - For details see www.dekloe.be Occurrences Name 3 A & R (pub) 3 A-R Editions (pub) 2 A.B.C. TV 1 A.G.I.F.C. 3 Aamer, Meysam 7 Aandahl, Vaughan 2 Aarestrup, Emil 2 Aaron Shearer Foundation 1 Aaron, Bernard A. 2 Aaron, Wylie 1 Abaca String Band 1 Abadía, Conchita 1 Abarca Sanchis, Juan 2 Abarca, Atilio 1 Abarca, Fernando 1 Abat, Joan 1 Abate, Sylvie 1 ABBA 1 Abbado, Claudio 1 Abbado, Marcello 3 Abbatessa, Giovanni Battista 1 Abbey Gate College (edu) 1 Abbey, Henry 2 Abbonizio, Isabella 1 Abbott & Costello 1 Abbott, Katy 5 ABC (mag) 1 Abd ar-Rahman II 3 Abdalla, Thiago 5 Abdihodzic, Armin 1 Abdu-r-rahman 1 Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Sayyd 1 Abdula, Konstantin 3 Abe, Yasuo 2 Abe, Yasushi 1 Abel, Carl Friedrich 1 Abelard 1 Abelardo, Nicanor 1 Aber, A. L. 4 Abercrombie, John 1 Aberle, Dennis 1 Abernathy, Mark 1 Abisheganaden, Alex 11 Abiton, Gérard 1 Åbjörnsson, Johan 1 Abken, Peter 1 Ablan, Matthew 1 Ablan, Rosilia 1 Ablinger, Peter 44 Ablóniz, Miguel 1 Abondance, Florence & Pierre 2 Abondance, Pierre 1 Abraham Goodman Auditorium 7 Abraham Goodman House 1 Abraham, Daniel 1 Abraham, Jim 1 Abrahamsen, Hans Page 1 SoundboardIndexNames.txt 1 Abrams (pub) 1 Abrams, M. H. 1 Abrams, Richard 1 Abrams, Roy 2 Abramson, Robert 3 Abreu 19 Abreu brothers 3 Abreu, Antonio 3 Abreu, Eduardo 1 Abreu, Gabriel 1 Abreu, J. -

Download Download

МUSIC SUMMER FESTIVALS AS PROMOTERS OF THE SPA CULTURAL TOURISM: FESTIVAL OF CLASSICAL MUSIC VRNJCI Smiljka Isaković1, Jelena Borović-Dimić2 Abstract This paper is dedicated to the music summer festivals, a hallmark of the local community and the holder of the economic development of the region and the society, from ancient times to the present day. Special emphasis is placed on the International Festival of classical music "Vrnjci", held in Belimarković mansion in July, organized by the Homeland Мuseum – Castle of Culture of Vrnjaĉka Banja. A dramatic development of high technologies brought forth a new era based on conceptual creativity. Leisure time is prolonged, while tourism as one of the activities of spending leisure time is changing from passive to active. The cultural sector is becoming an important partner in the economic development of countries and cultural tourism is gaining in importance. Festival tourism in this country must be supported by the wider community and the state because the quality of cultural events makes us an equal competitor on the global tourism market. Keywords: cultural tourism, festivals, art, music, local self governments. Cultural Tourism The middle of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries can be called the period of tourism, since Stendhal popularized this term in France with his book "Memoirs of a tourist" (1838) and Englishman Thomas Cook opened his travel agency in 1841. Modern tourism experienced its first expansion between 1850 and 1870, enabled by the major railways networking in Europe -

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents Grußwort / Greeting........................................... 7 II - Psalmvertonungen und Gebete / Vorwort / Preface................................................ 9 Psalm Settings and Prayers.............. 49 Ganz Europa im Fokus • Die Auswahl als repräsentativer Zeitspiegel und abgestimmt auf die heutige Praxis • Dominus regit m e.................................................. 50 Zur Gliederung der Chorstücke - Ein reichhaltiges Chorreper Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) toire • A cappella oder mit Begleitung? • Zur Interpretation - W ie der Hirsch schreiet / As the Hart Panteth.......... 58 Geistliche Chormusik im „langen 19. Jahrhundert" • Zur Heinrich Bellermann (1832-1903) Verwendung des Romantik-Begriffs im Titel des Chorbuchs • Editorische Anmerkungen - Zu den verwendeten Bibel Sicut cervus........................................................... 64 versionen • Hilfestellungen für die Probenarbeit Charles Gounod (1818-1893) All of Europe in the limelight • The selection as a represen Kot po mrzli studencini / As the Thirsting Hart Pants.. 67 tative reflection of the times, yet in tune with modern Hugolin Sattner (1851-1934) practice - The organisation of the choral pieces • A rich Sende dein Licht (Kanon) / and extensive choral repertoire • A cappella or with accom Send Out Thy Light (Canon)............................... 68 paniment? • Concerning performance • Sacred choral music Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853) in the "long nineteenth century" • On the use of the term "Romantik" in the title of this choir -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

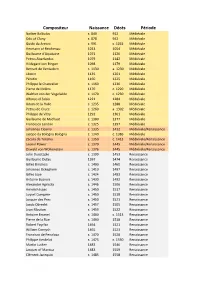

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

37563/Clasical Guitar/229-249

229 Classical Guitar 230 Solo Guitar Literature by Composer 242 Guitar Collections 245 Guitar Duos 246 Guitar Ensembles 247 Guitar with Various Instruments 249 Voice and Guitar 249 Mandolin 230 SOLO GUITAR LITERATURE J.S. BACH ______00006366 Bach Again for Guitar (Block) SOLO GUITAR Contents: Minuet In G; Gavotte; Minuet; Bouree In Em; Little Prelude; Gavotte In D; Short Prelude; Menuet; LITERATURE Fantasia In C Minor; Bouree. Marks M834.....................................................................$4.95 ______00006329 Bach for Guitar (Block) ANONYMOUS Contents: Minuet; Jesu, Joy Of Man’s Desiring; Rondo- ______50562985 Dindandon et tambourin joli (Pujol 2001) Gavotte; Awake, Awake, A Voice Is Calling; Gavotte; Minuet Eschig ME0784300........................................................$12.95 In G Minor; Sarabande; Polonaise; Concerto In The Italian Style ______00663025 Malagueña (Paul Henry) Marks M366.....................................................................$4.95 Hal Leonard .....................................................................$3.95 ______50250440 Bach For My Guitar ______50560305 Scottisch Madrilene (Pujol 1088) Ricordi R132592............................................................$12.00 Eschig ME0729700..........................................................$6.95 ______50560002 Canon (Pujol 2006) DIONISIO AGUADO Eschig ME0788100..........................................................$6.95 ______50015050 50 Studies (Gonzales) ______00315184 Classical Guitar of Bach Ricordi RLD546 ............................................................$10.95 -

2017 Winter Classical Update

HAL LEONARD WIN T ER 2017 UPDATE Within this newsletter you will find PIANO a recap of recent classical releases. The following classical catalogs are BRUCE ADOLPHE: BÉLA BARTÓK: distributed by Hal Leonard: SEVEN THOUGHTS THE FIRST TERM AT CONSIDERED AS MUSIC THE PIANO Amadeus Press Lauren Keiser Music Publishing 18 ELEMENTARY PIECES Associated Music This set of virtuosic pieces, ed. Monika Twelsiek Publishers commissioned by Italian pianist Schott Boosey & Hawkes Carlo Grante, is inspired by A collection of beginning piano Bosworth Music philosophical statements from pieces based on folk songs and seven historical figures: Heraclitus, dances. A perfect introduction to Bote & Bock Rainer Maria Rilke, Franz Kafka, Bartók’s Mikrokosmos Book 1. CD Sheet Music Ralph Waldo Emerson, Novalis, Chester Music Chief Seattle, and Shankara. DSCH 00217195 Piano Solo ...................................................... $19.95 49031519 Piano Solo .......................................................$11.99 Editio Musica Budapest Editions Durand Edition Egtved JOHANN SEBASTIAN BÉLA BARTÓK: SONATINE Editions Max Eschig BACH: CHORALE ed. László Somfai Editions Musicales PRELUDES Henle Urtext Editions Transatlantique ARRANGEMENT FOR PIANO BY Bartók used different melodies Editions Salabert FERRUCCIO BUSONI taken from Romanian Bartók Ediciones ed. Christian Schaper, Ullrich based this piece on a series Joaquín Rodrigo Scheideler of piano transcriptions of Edward B. Marks Henle Urtext Editions Romanian folk melodies. This Music Company Busoni transcribed these chorale Urtext edition is extracted preludes in ‘chamber music from the new Complete Eulenburg style,’ suitable for advanced Edition and includes an Forberg pianists. The appendix includes explanation of how to play G. Henle Verlag an eleventh chorale prelude published for the first time: Busoni’s the very complex piano notation by Bartók himself and G. -

A Schubertiade for Biedermeier Flute & Guitar

Gotham Early Music Scene (GEMS) presents Thursday, March 11, 2021 1:15 pm Streamed to midtownconcerts.org, YouTube, and Facebook Taya König-Tarasevich ~ Romantic flute Daniel Swenberg ~ Romantic guitar A Midday Nocturne: A Schubertiade for Biedermeier Flute & Guitar Abendlied Robert Schumann (1810–1856) [arr. J.K. Mertz] An Die Sonne Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Romanze from Rosamunde Franz Schubert Am Fenster Franz Schubert Mouvement de prière religieuse Fernando Sor (1778–1839) Nocturne Friedrich Burgmüller (1806–1874) Nacht und Träume Franz Schubert [arr. Diabelli] 9 Waltzes from D. 365 original Dances Franz Schubert [arr. Diabelli] Mondnacht Robert Schumann Taya König-Tarasevich: Romantic flute by Stefan Koch 1830 (restored M. Wenner 2019) Daniel Swenberg: 8-string guitar after Ries (Kresse 2012) Midtown Concerts are produced by Gotham Early Music Scene, Inc., and are made possible with support from St. Bartholomew’s Church, The Church of the Transfiguration, The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural affairs in partnership with the City Council; the Howard Gilman Foundation; and by generous donations from audience members. Gotham Early Music Scene, 340 Riverside Drive, Suite 1A, New York, NY 10025 (212) 866-0468 Joanne Floyd, Midtown Concerts Manager Paul Arents, House Manager Toby Tadman-Little, Program Editor Live stream staff: Paul Ross, Dennis Cembalo, Adolfo Mena Cejas, Howard Heller Christina Britton Conroy, Make-up Artist Gene Murrow, Executive Director www.gemsny.org Notes on the Program, Instruments, Editions, and Arrangements by Daniel Swenberg I suppose this program gradually formed over the years I got to know Taya and we shared our love of German Romantic poetry, particularly the song or Lied repertoire of Schubert and Schumann. -

A Historical and Critical Analysis of 36 Valses Di Difficolta Progressiva, Op

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 A Historical and Critical Analysis of 36 Valses di Difficolta Progressiva, Op. 63, by Luigi Legnani Adam Kossler Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A HISTORICAL AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF 36 VALSES DI DIFFICOLTA PROGRESSIVA, OP. 63, BY LUIGI LEGNANI By ADAM KOSSLER A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Adam Kossler defended this treatise on January 9, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bruce Holzman Professor Directing Treatise Leo Welch University Representative Pamela Ryan Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my guitar teachers, Bill Kossler, Dr. Elliot Frank, Dr. Douglas James and Bruce Holzman for their continued instruction and support. I would also like to thank Dr. Leo Welch for his academic guidance and encouragement. Acknowledgments must also be given to those who assisted in the editing process of this treatise. To Ruth Bass, Dr. Leo Welch, Bill Kossler, Lauren Kossler and Jamie Parks, I am forever thankful for your contributions. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical -

La Correspondencia Entre Louis Viardot Y Santiago De Masarnau (1832-1838)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Revistas Científicas Complutenses MARÍA NAGORE FERRER Universidad Complutense de Madrid La correspondencia entre Louis Viardot y Santiago de Masarnau (1832-1838). Nuevos datos sobre José Melchor Gomis Se presentan en este artículo las cartas y notas manuscritas dirigidas por el escritor e hispanista francés Louis Viardot al compositor Santiago de Masarnau conservadas en el Archivo Histórico Nacional. Pese a constituir un corpus pequeño, se trata de una correspondencia inédita que aporta datos de interés relacionados especialmente con los últimos años y el fallecimiento del compositor José Melchor Gomis, amigo común de ambos. Esta documentación se completa con los artículos necrológicos escritos por Viardot en el periódico francés Le Siècle y por Masarnau en El Español tras el fallecimiento de Gomis. Palabras clave: Louis Viardot, Santiago de Masarnau, José Melchor Gomis, música siglo XIX. This article presents the manuscript letters and notes the French hispanist Louis Viardot sent the compos- er Santiago de Masarnau held at the Archivo Histórico Nacional. Despite forming a small collection of writ- ings, this unpublished correspondence provides interesting information especially regarding the late years and death of their common friend, the composer José Melchor Gomis.This documentation is completed with the obit- uaries Viardot published in French periodical Le Siècle and Masarnau in El Español following Gomis’s death. Keywords: Louis Viardot, Santiago de Masarnau, José Melchor Gomis, nineteenth-century music. Presentamos en este artículo las cartas y notas manuscritas dirigidas por el escritor e hispanista francés Louis Viardot (1800-1883) al compositor Santiago de Masarnau (1805-1882) conservadas en el Archivo Histórico Nacional1.