William Reeves Bishop, Scholar, Antiquary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

Fleming-The-Book-Of-Armagh.Pdf

THE BOOK OF ARMAGH BY THE REV. CANON W.E.C. FLEMING, M.A. SOMETIME INCUMBENT OF TARTARAGHAN AND DIAMOND AND CHANCELLOR OF ARMAGH CATHEDRAL 2013 The eighth and ninth centuries A.D. were an unsettled period in Irish history, the situation being exacerbated by the arrival of the Vikings1 on these shores in 795, only to return again in increasing numbers to plunder and wreak havoc upon many of the church settlements, carrying off and destroying their treasured possessions. Prior to these incursions the country had been subject to a long series of disputes and battles, involving local kings and chieftains, as a result of which they were weakened and unable to present a united front against the foreigners. According to The Annals of the Four Masters2, under the year 800 we find, “Ard-Macha was plundered thrice in one month by the foreigners, and it had never been plundered by strangers before.” Further raids took place on at least seven occasions, and in 941 they record, “Ard-Macha was plundered by the same foreigners ...” It is, therefore, rather surprising that in spite of so much disruption in various parts of the country, there remained for many people a degree of normality and resilience in daily life, which enabled 1 The Vikings, also referred to as Norsemen or Danes, were Scandinavian seafarers who travelled overseas in their distinctive longships, earning for themselves the reputation of being fierce warriors. In Ireland their main targets were the rich monasteries, to which they returned and plundered again and again, carrying off church treasures and other items of value. -

D 1KB LI 1^1

.« p..^—»«=.».^»,— » ~-pppf^l^J^P^ :d 1KB LI 1^1 c?-/? mlTeraiiir Cakntrar, /(,'/; uiB y:i:Ai!. 19 06-19 7 Vol. II m. :i,(Mjin:«, FJOiAis, and co,, i,n:,, i;i;Ai' L0>'1>0X. XEW YUEK, AN D 1' • - 1907, ^-'V?^'c«-a?or. vw. ~jun^>c<x-.oiEMMueHlBCdaB9 tiB I tyjwmmwpp Large 8vo, C/ofh. pp. xxvi + 606. Price 70/6 net CATALOGUE MANUSCRIPTS Hibrarp of €rinitp College, SDublin TO WHICH IS ADOKD A LIST OF THE FAGEL COLLECTION OF MAPS IN THE SAME LIBRARY COMPILKD BY T. K. ABBOTT, B.D., D.Litt. (librarian) DUBLIN: HODGES, FIGGIS, AND CO., Limited. LONDON : LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO. ['] THE BOOK OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, 1591—1891- Descriptive and Historical Account of the College from its Foundation, with 22 Full-page Plates, and 50 Illustra- tions in the Text, consisting of Views, Plans, and Portraits of Famous Members. CONTENTS. CHAPS. i.-iv. —From the Foundation to the close of the Eighteenth Century. By the Eev. J. P. Mahaffy, d.d. v.— During the Nineteenth Century. By the Eev. J. W. Stubbs, d.d. VI. —The Observatory, Dunsink. By Sir Eobeut Ball, ll.d. VII. —The Library. By the Eev. T. K.Abbott, b.d., litt.d.. Librarian, VIII. —The Early Buildings. By Ulick E. Burke, m.a. IX.—Distinguished Graduates. By "W. M'Neile Dixon, ll.r. X.— The College Plate. By the Eev. J. P. Mahaffy, d.d. XI. —The Botanical Gardens and Herbarium. By E. Perceval Wbioht, M.D. XII. —The University and College Officers, 1892. Ode for the Tercentenary Festival. -

List of Manuscript and Printed Sources Current Marks and Abreviations

1 1 LIST OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINTED SOURCES CURRENT MARKS AND ABREVIATIONS * * surrounds insertions by me * * variant forms of the lemmata for finding ** (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted by me + + surrounds insertion from the addenda ++ (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted from addenda † † marks what is (I believe) certainly wrong !? marks an unidentified source reference [ro] Hogan’s Ro [=reference omitted] {1} etc. different places but within a single entry are thus marked Identical lemmata are numbered. This is merely to separate the lemmata for reference and cross- reference. It does not imply that the lemmata always refer to separate names SOURCES Unidentified sources are listed here and marked in the text (!?). Most are not important but they are nuisance. Identifications please. 23 N 10 Dublin, RIA, 967 olim 23 N 10, antea Betham, 145; vellum and paper; s. xvi (AD 1575); see now R. I. Best (ed), MS. 23 N 10 (formerly Betham 145) in the Library of the RIA, Facsimiles in Collotype of Irish Manuscript, 6 (Dublin 1954) 23 P 3 Dublin, RIA, 1242 olim 23 P 3; s. xv [little excerption] AASS Acta Sanctorum … a Sociis Bollandianis (Antwerp, Paris, & Brussels, 1643—) [Onomasticon volume numbers belong uniquely to the binding of the Jesuits’ copy of AASS in their house in Leeson St, Dublin, and do not appear in the series]; see introduction Ac. unidentified source Acallam (ed. Stokes) Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), Acallam na senórach, in Whitley Stokes & Ernst Windisch (ed), Irische Texte, 4th ser., 1 (Leipzig, 1900) [index]; see also Standish H. -

The Political Journal of Sir George Fottrell

THE POLITICAL JOURNAL OF SIR GEORGE FOTTRELL 13 Jany. 1885 I think it may perhaps at some future stage of Irish politics prove useful to have from an eye witness some notes of the events now passing in Ireland or rather some notes of the inner working of the Government and of the Irish party.I have rather exceptional opportunities of noting their working. I have since I attained manhood been a consistent Nationalist and I believe that the leading men on the national side have confidence in my honour and consistency. On the other hand I am a Crown official & I am an intimate personal friend of Sir Robert Hamilton,1 the Under Secretary for Ireland. My first introduction to him took place about 18 months ago. I was introduced to him by Robert Holmes,2 the Treasury Remembrancer. At that time Sir Robert was Mr.Hamilton & his private secretary was Mr.Clarke Hall who had come over temporarily from the Admiralty. Mr. Hamilton was himself at that time only a temporary official. Shortly afterwards he was induced to accept the permanent appointment as Under Secretary. From the date of my first introduction to him up to the present our acquaintance has steadily developed into a warm friendship and I think that Sir Robert Hamilton now probably speaks to me on Irish matters more freely than to anyone else. I have always spoken to him with similar freedom and whether my views were shared by him or were at total variance with his I have never concealed my opinion from him. -

Smythe-Wood Series B

Mainly Ulster families – “B” series – Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Ulster ‘SERIES B’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ACR: Acadian Recorder LON The London Magazine ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard BAA Ballina Advertiser LUR Lurgan Times BAI Ballina Impartial MAC Mayo Constitution BAU Banner of Ulster NAT The Nation BCC Belfast Commercial Chronicle NCT -

Hazlett-Campbell-Est

Series Description St. Louis Circuit Court Records Hazlett Kyle Campbell Case St. Louis Union Trust Company, et al. v Clarke, Charles H., et al – 23694-C Abstract: The Hazlett Kyle Campbell Case consists of 17 cubic feet of court papers, transcripts, and exhibits ranging in date from 1938 through 1944. The documents in this collection offer a wealth of information on social, cultural, and economic history as it relates to one of St. Louis’s preeminent nineteenth-century families. Provenance: Office of the Circuit Clerk, City of St. Louis. This case originated with the death of Hazlett Kyle Campbell in March 1938. He left behind an estate valued at approximately $1,850,000. More than 1,000 people eventually came forward claiming to be heirs of this estate. The documents included in this finding aid were filed in the St. Louis Circuit Court between 1938 and 1944. Missouri State Archives staff processed and prepared the materials for microfilm in 2006-2007. Series Title: St. Louis Union Trust Company, et al. v Clarke, Charles H., et al - 23694-C Series Inclusive Dates: 1938-1944 Volume: 17 cubic feet (16 cubic feet of legal size file folders and 3 oversized boxes) Physical Description: The series consists of court papers, transcripts and exhibits (photographs, birth and death records, lineage charts, diaries, wills, bibles, etc.). The majority of these documents are original, however, there exists a considerable number of photostat copies as well. All documents have been flattened and cleaned of dirt and dust that accumulated through the years. Items used to attach documents, such as grommets, straight pins, ribbons, paper clips, and staples have been removed to allow for filming and scanning. -

Lviemoirs of JOHN KNOX

GENEALOGICAL lVIEMOIRS OF JOHN KNOX AXIJ OF THE FAMILY OF KNOX BY THE REV. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D. fF'.LLOW OF THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAXD, FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF XORTHER-N A:NTIQ:;ARIES, COPENHAGEN; FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW SOCTH WALES, ASSOCIATE OF THE IMPRRIAL ARCIIAWLOGICAL SOCIETY OF Rl'SSIA, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF QL'EBEC, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA, A!'i'D CORRESPOXDING MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLA:ND PREF ACE. ALL who love liberty and value Protestantism venerate the character of John Knox; no British Reformer is more entitled to the designation of illustrious. By three centuries he anticipated that parochial system of education which has lately become the law of England; by nearly half that period he set forth those principles of civil and religious liberty which culminated in a system of constitutional government. To him Englishmen are indebted for the Protestant character of their "Book of Common Prayer;" Scotsmen for a Reforma tion so thorough as permanently to resist the encroachments of an ever aggressive sacerdotalism. Knox belonged to a House ancient and respectable; but those bearing his name derive their chiefest lustre from 1eing connected with a race of which he was a member. The family annals presented in these pages reveal not a few of the members exhibiting vast intellectual capacity and moral worth. \Vhat follows is the result of wide research and a very extensive correspondence. So many have helped that a catalogue of them ,...-ould be cumbrous. -

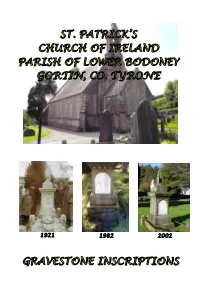

St. Patrick's C of I, Gortin

1921 1982 2002 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN Thanks to Hazel Robinson for patiently helping to decipher and make the gravestone recordings on our many journeys to this peaceful graveyard of our ancestors. Colour photographs by Ann Robinson. Black & White photograph courtesy of Ann Dark. © 2017 A.K. ROBINSON 2 ST. PATRICK’S PARISH CHURCH, LOWER BADONEY, GORTIN ST. PATRICK’S CHURCH OF IRELAND, PARISH OF LOWER BODONEY (BADONEY), GORTIN, CO. TYRONE. The Parish of Badoney was originally a very large parish, stretching up the Glenelly Valley, with the oldest church site in the townland of Glenroan. This church is also called St. Patrick and this part of the parish eventually became Upper Badoney. The parish of Badoney was separated into two parts in 1730 and the first church of Lower Badoney, St. Patrick’s, was built in the village of Gortin. It was not until 1774 that the parish of Lower Badoney was constituted. The two parts were reunited again in 1924. In 1856 a new church was built in Lower Badoney at a cost of £1,921-15-00. This is the current church and is on a slightly different site to the older one. For many years parts of the old church, and the school, could be seen in the graveyard. In 1939 the graveyard was measured by J.C.M. Knox, Londonderry. In the 1980s all signs of the old church were removed when the graveyard was “tidied up.” From the First edition of the Ordnance Survey Maps (1832-1846) the position of the first church can be seen, along with the school. -

St. Grellan, Patron of Hy-Maine, Counties of Galway and Roscommon. John O'hanlon Introduction—Hy-Maine, Its Boundaries and O

St.Grellan,PatronofHy-Maine, counties of Galway and Roscommon. John O’Hanlon [Fifth or Sixth centuries.] CHAPTER I. Introduction—Hy-Maine, its boundaries and original inhabitants—The Firbolgs—Maine Mor succeeds and gives name to the territory—Afterwards occupied by the O’Kellys— Authorities for the acts of St. Grellan—His descent and birth—Said to have been a disciple of St. Patrick—A great miracle wrought by St. Grellan at Achadh Fionnabrach. OF this holy man Lives have been written ; while one of them is to be found in a Manu- script of the Royal Irish Academy, [1] and another among the Irish Manuscripts, in the Royal Library of Bruxelles. Extracts containing biographical memoranda relating to him are given by Colgan, [2] and in a much fuller form by Dr. John O’Donovan, as taken from the Book of Lecan. [3] There is also a notice of him, in the “ Dictionary of Christian Biography.” [4] Colgan promised to present his Life in full, at the 10th of November ; but he did not live to fulfil such promise. Besides the universal reverence and love, with which Ireland regards the memory of her great Apostle, St. Patrick, most of our provincial districts and their families of distinction have patron saints, for whom a special veneration is entertained. Among the latter, St. Grellan’s name is connected with his favoured locality. The extensive territory of Hy-Many is fairly defined, [5] by describing the northern line as running from Ballymoe, County of Galway, to Lanesborough, at the head of Lough Ree, on the River Shannon, and in the County of Roscommon. -

The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, C. 1800-1837

The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, c. 1800-1837 Nicholas Andrew Dixon Pembroke College, Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. November 2018 Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. Nicholas Dixon November 2018 ii Thesis Summary The Activity and Influence of the Established Church in England, c. 1800-1837 Nicholas Andrew Dixon Pembroke College, Cambridge This thesis examines the various ways in which the Church of England engaged with English politics and society from c. 1800 to 1837. Assessments of the early nineteenth-century Church of England remain coloured by a critique originating in radical anti-clerical polemics of the period and reinforced by the writings of the Tractarians and Élie Halévy. It is often assumed that, in consequence of social and political change, the influence of a complacent and reactionary church was irreparably eroded by 1830. -

Church Records

CHURCH RECORDS WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH COMPILED AND EDITED BY REV. NORMAN CARLYSLE YOUNG, M.Div.; M.Ed. AND NAOMI KATHLEEN IVEY HORNER UPDATED June 30, 2021 AN HISTORICAL RECORDS VOLUME PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE ARCHIVES & HISTORY MINISTRY TEAM Printed by McElvany & Company Printing and Publishing 1 Copyright © 2021 by The Western Pennsylvania Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church All Rights Reserved 2 PREFACE The Historical Volume Church Records Western Pennsylvania Conference of The United Methodist Church was last printed in 2003. In order to keep the Church Records current, Janet & Norman C. Young were retained to update the more recent appointments and make necessary corrections as new information became available. Since their death, Naomi Horner has graciously volunteered to continue updating the volume. New information comes from the readers making corrections and suggestions. New information also comes from Naomi’s continued research on the companion volume Pastoral Records. The Western Pennsylvania Commission on Archives & History decided to make this revision and update available on these webpages www.wpaumc.org0H so that the most current information remains accessible and for corrections to continue to refine the document. This volume has had long history of Revision. Described by Herbert E. Boyd in his 1957 volume on the Erie Methodist Preface as a “compendium…intended primarily as an administrative tool.” He then credits forerunners back to 1898. At that time, this primarily contained Pastoral Records. Grafton T. Reynolds edited for the Pittsburgh Methodist Episcopal Church a similar volume through 1927. W. Guy Smeltzer divided his 1969 revision between chapters on Pastoral Records and Church Records.