How Future-Focused Elementary School Cultures Influence the Future Aspirations of Low-Income Students: a Comparative Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): an Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2003 The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Terrance Gerard Galvin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, European History Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Galvin, Terrance Gerard, "The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment" (2003). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 996. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Abstract In examining select works of English architects Joseph Michael Gandy and Sir John Soane, this dissertation is intended to bring to light several important parallels between architectural theory and freemasonry during the late Enlightenment. Both architects developed architectural theories regarding the universal origins of architecture in an attempt to establish order as well as transcend the emerging historicism of the early nineteenth century. There are strong parallels between Soane's use of architectural narrative and his discussion of architectural 'model' in relation to Gandy's understanding of 'trans-historical' architecture. The primary textual sources discussed in this thesis include Soane's Lectures on Architecture, delivered at the Royal Academy from 1809 to 1836, and Gandy's unpublished treatise entitled the Art, Philosophy, and Science of Architecture, circa 1826. -

2Bbb2c8a13987b0491d70b96f7

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS’ FORBES PIGMENT COLLECTION Yoko Ono “If people want to make war they should make a colour war, and paint each others’ cities up in the night in pinks and greens.” Foreword p.6 Introduction p.12 Red p.28 Orange p.54 Yellow p.70 Green p.86 Blue p.108 Purple p.132 Brown p.150 Black p.162 White p.178 Metallic p.190 Appendix p.204 8 AN ATLAS OF RARE & FAMILIAR COLOUR FOREWORD 9 You can see Harvard University’s Forbes Pigment Collection from far below. It shimmers like an art display in its own right, facing in towards Foreword the glass central courtyard in Renzo Piano’s wonderful 2014 extension to the Harvard Art Museums. The collection seems, somehow, suspended within the sky. From the public galleries it is tantalising, almost intoxicating, to see the glass-fronted cases full of their bright bottles up there in the administra- tive area of the museum. The shelves are arranged mostly by hue; the blues are graded in ombre effect from deepest midnight to the fading in- digo of favourite jeans, with startling, pleasing juxtapositions of turquoise (flasks of lightest green malachite; summer sky-coloured copper carbon- ate and swimming pool verdigris) next to navy, next to something that was once blue and is now simply, chalk. A few feet along, the bright alizarin crimsons slake to brownish brazil wood upon one side, and blush to madder pink the other. This curious chromatic ordering makes the whole collection look like an installation exploring the very nature of painting. -

The Great Practice Master

The Great Practice Whit Griffin 1 The Great Practice Whit Griffin Table Of Contents The Great Practice 3 The Poetics Of Reincarnation 166 A Selected / Suggested Bibliography 182 Acknowledgments 187 2 The Great Practice Whit Griffin The ferocious alligator pisses the tobacco plant. The crying baboons who piss each hour during the equinoxes. Urinating on cereal grains to test for pregnancy. The birth of the divine child, whether he bears the name Horus, Osiris, Helios, Dionysus, or Aeon, was celebrated in the Koreion in Alexandria, in the temple dedicated to Kore, on the day of the winter solstice, when the new divine light is born. The Great Central Sun of Sacred Power. I am perception and Knowledge, uttering a Voice by means of Thought. I am the real Voice. The voice of the sun. The ring of deliverance. The silver apples of wisdom. A wisdom of loving participation. The tortoise stands in opposition to the sun. In the mythology of the oldest known Semitic-Babylonian calendar, the moon signifies life; the sun signifies death. 3 The Great Practice Whit Griffin Some say poets invented the gods, the Trojan War was directed by hallucinations. Was the Israelite exodus from Egypt contemporaneous with the Trojan War? * The lotus blossom of psychic flowering. Energy with the quality of mind. The blond moon. The soul is hundreds of thousands of times finer and more powerful than intelligence. A stream of wind is blowing through the tube of the sun. As the Gorgon is the night sun. As the moon is the night snake that walks in the water. -

Acacia Fall 2020 Rights List

Acacia Acacia House House Catalogue Summer Fall - 2020Fall 2019 Catalogue 1 Dear Reader, We invite you to look at our Fall 2020 International Rights Catalogue, a list that includes works by adult authors represented by Acacia House, but also recent and forthcoming titles from: Douglas & McIntyre; Fifth House; Fitzhenry & Whiteside; Harbour Publishing; Lilygrove; NeWest Press; New Star Books; Shillingstone: Véhicule; West End Books; Whitecap Books and Words Indeed whom we represent for rights sales. We hope you enjoy reading through our catalogue. If you would like further information on any title(s),we can be reached by phone at (519) 752-0978 or by e-mail: [email protected] — or you can contact our co-agents who handle rights for us in the following languages and countries: Bill Hanna Photo© Frank Olenski Brazilian: Dominique Makins, DMM Literary Management Chinese: Wendy King, Big AppleTuttle-Mori Agency Serbo Croatian: Reka Bartha Katai & Bolza Literary Agency Dutch: Linda Kohn, Internationaal Literatuur Bureau German: Peter Fritz, Christian Dittus, Antonia Fritz, Paul & Peter Fritz Agency Greek: Nike Davarinou, Read ’n Right Agency Hungarian: Lekli Mikii, Katai & Bolza Literary Agency Indonesia: Santo Manurung, Maxima Creative Agency Israel: Geula Guerts, The Deborah Harris Agency Italian: Daniela Micura, Daniela Micura Literary Agency Japanese: Miko Yamanouchi, Japan UNI Agency Korean: Duran Kim, Duran Kim Literary Agency Malaysia: Wendy King, Big AppleTuttle-Mori Agency Polish: Maria Strarz-Kanska, Graal Ltd. Portugal: Anna Bofill, Carmen Balcells S.A Kathy Olenski Photo☺ Frank Olenski Romanian: Simona Kessler, Simona Kessler Agency Russian: Alexander Korzhenevsky, Alexander Korzhenevski Table of Contents Agency Fiction 3 South Africa: TerryTemple, International Press Agency Historical Fiction 21 Scandinavia: Anette Nicolaissen, A. -

The Expression of Sacred Space in Temple Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository EXPRESSONS OF SACRED SPACE: TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST by Martin J Palmer submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in the subject Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promoter: Prof. P S Vermaak February 2012 ii ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to identify, isolate, and expound the concepts of sacred space and its ancillary doctrines and to show how they were expressed in ancient temple architecture and ritual. The fundamental concept of sacred space defined the nature of the holiness that pervaded the temple. The idea of sacred space included the ancient view of the temple as a mountain. Other subsets of the basic notion of sacred space include the role of the creation story in temple ritual, its status as an image of a heavenly temple and its location on the axis mundi, the temple as the site of the hieros gamos, the substantial role of the temple regarding kingship and coronation rites, the temple as a symbol of the Tree of Life, and the role played by water as a symbol of physical and spiritual blessings streaming forth from the temple. Temple ritual, architecture, and construction techniques expressed these concepts in various ways. These expressions, identified in the literary and archaeological records, were surprisingly consistent throughout the ancient Near East across large expanses of space and time. Under the general heading of Techniques of Construction and Decoration, this thesis examines the concept of the primordial mound and its application in temple architecture, the practice of foundation deposits, the purposes and functions of enclosure walls, principles of orientation, alignment, and measurement, and interior decorations. -

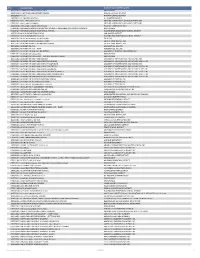

List of Schools and CTDS

CTDS SCHOOL NAME DISTRICT OR CHARTER HOLDER 108731101 A CHILD'S VIEW SCHOOL-CLOSED UNAVAILABLE 120201114 A J MITCHELL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL NOGALES UNIFIED DISTRICT 100206038 A. C. E. MARANA UNIFIED DISTRICT 118720001 A+ CHARTER SCHOOLS A+ CHARTER SCHOOLS 078707202 AAEC - PARADISE VALLEY ARIZONA AGRIBUSINESS & EQUINE CENTER, INC. 078993201 AAEC - SMCC CAMPUS ARIZONA AGRIBUSINESS & EQUINE CENTER, INC. 130201016 ABIA JUDD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PRESCOTT UNIFIED DISTRICT 078689101 ABRAHAM LINCOLN PREPARATORY SCHOOL: A CHALLENGE FOUNDATION ACADEMY UNAVAILABLE 070406167 ABRAHAM LINCOLN TRADITIONAL SCHOOL WASHINGTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DISTRICT 100220119 ACACIA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL VAIL UNIFIED DISTRICT 070406114 ACACIA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL WASHINGTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DISTRICT 108506101 ACADEMY ADVENTURES MIDTOWN ED AHEAD 108717103 ACADEMY ADVENTURES MID-TOWN EDUCATIONAL IMPACT, INC. 108717101 ACADEMY ADVENTURES PRIMARY SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL IMPACT, INC. 108734001 ACADEMY DEL SOL ACADEMY DEL SOL, INC. 108734002 ACADEMY DEL SOL - HOPE ACADEMY DEL SOL, INC. 088704201 ACADEMY OF BUILDING INDUSTRIES ACADEMY OF BUILDING INDUSTRIES, INC. 078604101 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE UNAVAILABLE 078604004 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE - CENTRAL ARIZONA-CLOSED UNAVAILABLE 108713101 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE, INC. 078242005 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE AVONDALE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078270001 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE CAMELBACK ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE, INC. 078242002 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE DESERT SKY ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242004 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE GLENDALE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242003 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE PEORIA ADVANCED ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242006 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE SOUTH MOUNTAIN ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242001 ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. -

The Only Universal Monarchy F Reemasonry, Ritual, and Gender in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 1749-1803

The Only Universal Monarchy F reemasonry, Ritual, and Gender in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 1749-1803 Samuel Biagetti Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 ! ! © 2015 Samuel Biagetti all rights reserved ! ! Abstract The Only Universal Monarchy: F reemasonry, Ritual and Gender in Revolutionary Rhode Island, 1749-1803 Samuel Biagetti Historians, in considering Freemasonry in the eighteenth century, have tended to define it in political terms, as an expression of enlightened sociability and of the secular public sphere that supposedly paved the way for modern democracy. A close examination of the lodges in Newport and Providence, Rhode Island, between 1749 and 1804, disproves these received notions. It finds that, contrary to scholarly perception, Freemasonry was deeply religious and fervently committed to myth and ritual. Freemasonry in this period was not tied to any one social class, but rather the Fraternity attracted a wide array of mobile, deracinated young men, such as mariners, merchants, soldiers, and actors, and while it was religiously heterogeneous, the Fraternity maintained a close relationship with the Anglican Church. The appeal of Masonry to young men in Atlantic port towns was primarily emotional, offering lasting social bonds amidst the constant upheaval of the eighteenth century, as well as a ritually demarcated refuge from the patriarchal responsibilities of the male gender. Masonry celebrated the -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Ucicago.Edu

oi.ucicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.ucicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.ucicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.ucicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.ucicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Australia: Sydney and the Great Barrier Reef

Australia: Sydney and the Great Barrier Reef Whitman-Hanson Global Awareness Program School Trip - February 2020 Table of Contents Map of Australia ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Why travel? And, why travel to Australia? ............................................................................................... 5 Days 1-2: We’re airborne .............................................................................................................................. 8 Day 3: Welcome to Australia! ...................................................................................................................... 8 Sydney ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Day 4: National Opal Collection ................................................................................................................. 10 Land and Water ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Opals ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 Australian History .................................................................................................................................. -

Buddhist-Parables.Pdf

Buddhist Parables Translated from the original Pāli by Eugene Watson Burlingame Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Lecturer in Pāli (1917-1918) at Yale University A parable, O monks, I here give unto you, that ye may understand the meaning of the matter. Majjhima Nikāya, i. 117, 155. To my Grandmother who when I was a boy taught me letters and told me stories many and various 2 Table of Contents Preface Acknowledgments Introductory Note Note on Pronunciation of Pāli Names Bibliographical Note Chapter I: Parables from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences on The Gratefulness of Animals and the Ungratefulness of Man Chapter II: Parables from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences and from the Book of Discipline on Unity and Discord Chapter III: Parables from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences on Divers Subjects Chapter IV: Parables from the Book of the Buddha’s Previous Existences in Early and Late Forms Chapter V: Parables from Early Sources on Divers Subjects Chapter VI: Humorous Parables from Early and Late Sources Chapter VII: Parables from Various Sources on Death 3 Chapter VIII: Parables from the Long Discourses on the Subject: “Is there a Life after Death?” Chapter IX: Parables from Buddhaghosa’s Legends of the Saints Chapter X: Parables from Early Sources on the Doctrine Chapter XI: Similes and Short Parables from the Questions of Milinda Chapter XII: Parables from the Long Discourses on the Fruits of the Religious Life Chapter XIII: Parables from the Medium-Length Discourses on Two Kinds -

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING the GRADUATING CLASS So Enter That Daily Thou Mayest Grow in Knowledge Wisdom and Love

FALL COMMENCEMENT 2020 CELEBRATING THE GRADUATING CLASS So enter that daily thou mayest grow in knowledge wisdom and love. So enter that daily thou mayest grow in knowledge wisdom and love. To the Class of 2020, Congratulations on your graduation from Ohio University! You are one of the fortunate who has experienced the nation’s best transformative learning experience. This year has not been what any of us had planned, as the COVID-19 global pandemic changed all of our lives. I want to thank you for boldly responding to these historic changes by continuing to learn together, work together and support one another. You have shown great resilience as you navigated the many challenges of 2020 and I am very proud of you. Your class is truly special and will always be remembered at Ohio University for your spirit and fortitude. Your time at Ohio University prepared you for your future, and now you and your classmates are beginning your careers, advancing in new academic programs or taking on other challenges. I want you to know, though, that your transformation is not yet complete. For a true education does not stop with a diploma; it continues throughout every day of your life. I encourage you to take the lessons you have learned at Ohio University and expand upon them in the years to come. As you have already learned, the OHIO alumni network is a vast enterprise – accomplished in their respectable professions, loyal to their alma mater, and always willing to help a fellow Bobcat land that next job or find an apartment/realtor in a new city. -

Padre Agostino Gemelli and the Crusade to Rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part One

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2010 Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one J. Casey Hammond Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hammond, J. Casey, "Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3684. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3684 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3684 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Padre Agostino Gemelli and the crusade to rechristianize Italy, 1878–1959: Part one Abstract Padre Agostino Gemelli (1878-1959) was an outstanding figure in Catholic culture and a shrewd operator on many levels in Italy, especially during the Fascist period. Yet he remains little examined or understood. Scholars tend to judge him solely in light of the Fascist regime and mark him as the archetypical clerical fascist. Gemelli founded the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan in 1921, the year before Mussolini came to power, in order to form a new leadership class for a future Catholic state. This religiously motivated political goal was intended to supersede the anticlerical Liberal state established by the unifiers of modern Italy in 1860. After Mussolini signed the Lateran Pacts with the Vatican in 1929, Catholicism became the officialeligion r of Italy and Gemelli’s university, under the patronage of Pope Pius XI (1922-1939), became a laboratory for Catholic social policies by means of which the church might bring the Fascist state in line with canon law and papal teachings.