Race and Education: Another Look at the Missionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950

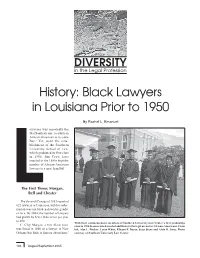

DIVERSITY in the Legal Profession History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950 By Rachel L. Emanuel ouisiana was reportedly the first Southern state to admit an African-American to its state Bar.1 Yet, until the esta- blishment of the Southern University School of Law, which graduated its first class in 1950, Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s kept the number of African-American lawyers to a mere handful. The First Three: Morgan, LBell and Chester The Seventh Census of 1853 reported 622 lawyers in Louisiana, but this infor- mation was not broken down by gender or race. By 1864, the number of lawyers had grown by fewer than seven per year to 698. With their commencement, members of Southern University Law Center’s first graduating C. Clay Morgan, a free black man, class in 1950 became much-needed additions to the legal arena for African-Americans. From was listed in 1860 as a lawyer in New left, Alex L. Pitcher, Leroy White, Ellyson F. Dyson, Jesse Stone and Alvin B. Jones. Photo Orleans but little is known about him.2 courtesy of Southern University Law Center. 104 August/September 2005 There were only four states reported to have admitted black lawyers to the bar prior to that time, none of them in the South. The states included Indiana (1860s), Maine (1844), Massachusetts (1845), New York (1848) and Ohio (1854). If, as is believed, Morgan was Louisiana’s first black lawyer,3 he would have been admitted to the Bar almost 10 years earlier than the average date for the other Southern states (Arkansas, 1866; Tennessee, 1868; Florida and Missis- sippi, 1869; Alabama, Georgia, Ken- tucky, South Carolina and Virginia, 1871; and Texas, 1873). -

Dillard University, Which Has Its Roots in Reconstruction, Has Outlasted Segregation, Discrimination and Hurricane Katrina

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Dillard 1718 ~ 2018 University was chartered on 300 June 6, 1930. TRICENTENNIAL THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION PHOTOS THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A group portrait of graduating nurses in front of Flint-Goodrich Hospital of Dillard University in 1932 Straight University in 1908, on Canal and Tonti streets Class President Nicole Tinson takes a selfie with then frst lady Michelle Obama during Dillard’s 2014 graduation. Dillard President Walter M.Kimbrough stands behind Obama. THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION New Orleans University in 1908, on St. Charles Avenue, was razed to make way for De La Salle High School. Dillard University, which has its roots in Reconstruction, has outlasted segregation, discrimination and Hurricane Katrina. THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE The university was created in 1930 from the opposition of the neighborhood. The first two historically black colleges — Straight president of the university, Will W. Alexander, University and Union Normal School — later was a white man because there were concerns named New Orleans University. that a white faculty wouldn’t want to answer The two schools were both created in 1868 to a black president. When Dillard opened its to educate newly freed African-Americans. new campus in 1935, it featured prominent fac- The schools offered professional training, in- ulty including Horace Mann Bond in psychol- The library of the new cluding in law, medicine and nursing. New ogy and education; Frederick Douglass Hall in Dillard University in 1935 Orleans University opened the Flint-Go- music; Lawrence D. -

A Study of Title Iii, Higher Education Act of 1965, and an Evaluation of Its Impact at Selected Predominantly Black Colleges

A STUDY OF TITLE III, HIGHER EDUCATION ACT OF 1965, AND AN EVALUATION OF ITS IMPACT AT SELECTED PREDOMINANTLY BLACK COLLEGES APPROVED: Graduate Committee: Dean of the]Graduate" School Gupta, Bhagwan S., A Study of Title III, Higher Educa- tion Act of 1965, and. an Evaluation of Xts Impact at Selected Predominantly Black Colleges. Doctor of Philosophy (Higher Education), December, 1971, 136 pp., 4 tables, bibliography, 66 titles. In the past half-century, comprehensive studies have been made by individuals and agencies to determine the future role of black institutions in American higher education. Early studies concerning black higher education suggested ways to improve and strengthen the black colleges; however, it was not until the year 1964 that major legislation, in the form of the Civil Rights Act, was passed. The purpose of this study was to describe the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, and to evaluate faculty development programs at selected black institutions in light of the objectives and guidelines established for the use of Title III funds. To carry out the purpose of this study, six questions were formulated. These questions dealt with (1) the eligibility requirements for colleges and univer- sities, (2) the Title III programs related to faculty development, (3) criteria to be used by institutions for selection of faculty members, (4) enhancing the chances for black institutions to compete with predominantly white institutions, (5) the effects of the programs in terms of short-term gains versus long-term gains, and (6) the insti- tutions ' ability or inability to take full advantage of opportunities provided under Title III. -

Tougaloo During the Presidency of Dr. Adam Daniel Beittel (1960-1964)

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2014 A Beacon of Light: Tougaloo During the Presidency of Dr. Adam Daniel Beittel (1960-1964) John Gregory Speed University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Other History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speed, John Gregory, "A Beacon of Light: Tougaloo During the Presidency of Dr. Adam Daniel Beittel (1960-1964)" (2014). Dissertations. 244. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/244 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi A BEACON OF LIGHT: TOUGALOO DURING THE PRESIDENCY OF DR. ADAM DANIEL BEITTEL (1960-1964) by John Gregory Speed Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 ABSTRACT A BEACON OF LIGHT: TOUGALOO DURING THE PRESIDENCY OF DR. ADAM DANIEL BEITTEL (1960-1964) by John Gregory Speed May 2014 This study examines leadership efforts that supported the civil rights movements that came from administrators and professors, students and staff at Tougaloo College between 1960 and 1964. A review of literature reveals that little has been written about the college‘s role in the Civil Rights Movement during this time. -

The Junior College

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1919, No. 35 - . THE JUNIOR COLLEGE By , F. M. McDOWELL GRACUAND COLLEGF- LAWN!. IOWA . - . Asetlit...4 -- .11443 ' . _ . - WASHINGTON comma:tn.PRINTING (*TICE . , 1919 ADDITIONAL COPIES 'WMB PUBLICATION NAT DB PROCURED PROM THE SUPERINTENDIENT OP DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OMCZ 'ASHINGTON, D. C. AT 32 CENTS PER COPY ---,A-Elf 2 4 0 1 2 7 OrC -.9 922 .o:p4=8 /9/ 9 CONTENTS. Page. Chapter I. Introduction 5 Purpose of the investigation 5 Method of and sources of data 7 Chapter II. The o'n and early development of the junior college 10 European suggestions 10 University of Michigan 11 University of Chicago. 11 University of California a 14 Chapter III. Influences tending to further the development of the junior college 16 Influences coming froni within the university 16 Influences coming from within the normal school.. 20 The demand for an extended high school. 22 The problem of the small college 28 Chapter Iy. Present status of the junior college 40 Recent growth of the junior college 40 Various types of junior colleges 42 Sources of support. 48 Courses of study 50 Training, experience, and work of teachers.. 53. Enrollment , 68 Graduates 68 Chapter V. Accrediting of junior colleges 71 ArizonaArkansas--California 71 GeorgiaIdahoIllinois 74 Indiana 76 Iowa--Kansas 77 Kentucky 80 MichiganMinnesota 81 MississippiMissouri MontanaNorth CarolinaNorth Dakota Nebraska 85 OhioOklahomaSouth DakotaTew 86 Utah "89 VirginiaWashington 90 West Virginia 91 Wisconsin 92 Summary of present standards. Chapter VI. *Summary and conclupion. 98 Appendixes . - A. Questionnaire to juniorcolleges, with list of institutions 108 B. -

The Sociopolitical Vessel of Black Student Life an Examination of How Context Influenced the Emergence of the Extracurriculum

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 9 March 2016 The oS ciopolitical Vessel of Black Student Life: An Examination of How Context Influenced the Emergence of the Extracurriculum Andre Perry Rashida Govan Christine Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Perry, A., Govan, R., & Clark, C. (2017). The ocS iopolitical Vessel of Black Student Life: An Examination of How Context Influenced the Emergence of the Extracurriculum. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.31390/taboo.15.1.09 Andre Perry, RashidaTaboo, SpringGovan, 2016 & Christine Clark 93 The Sociopolitical Vessel of Black Student Life An Examination of How Context Influenced the Emergence of the Extracurriculum Andre Perry, Rashida Govan, & Christine Clark The commercial success of the Denzel Washington-directed film, The Great Debaters (2007) [produced by Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Films], should inspire ad- ditional historical examinations of co-curricular or extracurricular activities in the first Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).1 While scholars in higher education who pay particular attention to HBCUs have responded mightily to issues involving curriculum (Anderson, 1988; Dunn, 1993; Jarmon, 2003), Little (2002) posited that the scant scholarly attention paid to America’s first black collegians’ extracurricular experiences ultimately limits our understanding of black education. The dominant framework for studying the emergence of extracurricular activities suggests that literary societies and fraternities leaked out of extremely tight curricula, which were bound by rigid religious protocols and parochial ideas of what made a “man of letters” (Church & Sedlak, 1976). -

3. Classification

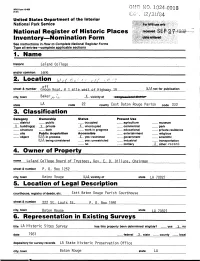

NPS Form 10-900 0MB NO, 1024-0018 (7-81) EXr. I2/3S/84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Lei and College and/or common same 2. Location $.-, r-/./* -i street & number Groom Road, (a 1 mile west, of Highway 19 N/A not for publication city, town Baker A vicinity of state LA code 22 county East Baton Rouge Parish code 033 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum _1_ building(s) X private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process X yes: restricted government scientific N/A being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military _X_ other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Leland College Board of Trustees, Rev. E. D. Billuos, Chairman street & number P. 0. Box 1252 city, town Baton Rouae M/A. vicinity of state LA 70821 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. East Baton Rouge Parish Courthouse street & number £22 St. Louis St. P. 0. Rnx 1QQ1 city, town Baton Rouqe state .A 70821 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title LA Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes X date 1981 federal X state county local depository for survey records LA State Historic Preservation Office city, town Baton Rouge state LA 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated unaltered X original sit e good ruins J(_altered moved date N/A . -

Black Expressions of Dillard University: How One Historically Black College Pioneered African American Arts

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 Black Expressions of Dillard University: How One Historically Black College Pioneered African American Arts Makenzee Brown University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Acting Commons, African American Studies Commons, Education Commons, Music Education Commons, Playwriting Commons, Public History Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Makenzee, "Black Expressions of Dillard University: How One Historically Black College Pioneered African American Arts" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2731. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2731 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Expressions of Dillard University How One Historically Black College Pioneered African American Arts A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Public History by Makenzee M. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Shawn C. Comminey, Ph.D. Professor Office Address: Department of History Southern University and A & M College Baton Rouge, LA 70813 (225) 771-4732 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Name of Institution Location Dates Attended Degree/Major -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- • Florida State University Tallahassee, FL 08/92-05/03 Ph.D. History Dissertation: “A History of Straight College, 1869-1932” • Southern University Baton Rouge, LA 08/88-07/90 M.A. Social Science (History) Thesis: “A History of Creoles and Mulattoes of African Ancestry in New Orleans, Louisiana” • Southern University Baton Rouge, LA 06/84-05/88 B.A. History PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCES • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Full Professor, 08/15 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Program Director/Associate Chair, 08/13-Present • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Chairman, 09/10-08/13 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Interim Chairman, 08/10-09/10 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Associate Professor, 08/10-07/15 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Assistant Professor, 08/95-07/10 • Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL, Adjunct Instructor, 01/95-04/95 • Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, Graduate Assistant, 08/93-04/94 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Adjunct Instructor, 08/90-05/92 • Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA, Graduate Assistant, 08/88-05/90 PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS/ORGANIZATIONS • Life Member, Southern Conference on African-American -

Horace Mann Bond Papers, 1830-1979 Finding Aid : Special

Special Collections and University Archives : University Libraries Horace Mann Bond Papers 1830-1979 (Bulk: 1926-1972) 169 boxes (84.5 linear ft.) Call no.: MS 411 Collection overview Educator, sociologist, scholar, and author. Includes personal and professional correspondence; administrative and teaching records; research data; manuscripts of published and unpublished speeches, articles and books; photographs; and Bond family papers, especially those of Horace Bond's father, James Bond. Fully represented are Bond's two major interests: black education, especially its history and sociological aspects, and Africa, particularly as related to educational and political conditions. Correspondents include many notable African American educators, Africanists, activists, authors and others, such as Albert C. Barnes, Claude A. Barnett, Mary McLeod Bethune, Arna Bontemps, Ralph Bunch, Rufus Clement, J.G. St. Clair Drake, W.E.B. Du Bois, Edwin Embree, John Hope Franklin, E. Franklin Frazier, W.C. Handy, Thurgood Marshall, Benjamin E. Mays, Kwame Nkrumah, Robert Ezra Park, A. Phillip Randolph, Lawrence P. Reddick, A.A. Schomburg, George Shepperson, Carter Woodson and Monroe Work. See similar SCUA collections: Africa African American Antiracism Civil rights Du Bois, W.E.B. Education Social change Social justice Background on Horace Mann Bond Horace Mann Bond was born on November 8, 1904 in Nashville, Tennessee. He was the son of James and Jane Alice Browne Bond, the fifth of their six children. His mother was a graduate of Oberlin College, and his father, a minister, held degrees from Berea College and Oberlin Seminary. James Bond's career included such positions as financial agent for Lincoln Institute in Kentucky, college pastor at Talladega College in Alabama, minister of an Atlanta church and director of the Kentucky Commission on Interracial Cooperation. -

Records of the National Negro Business League

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Black Studies Research Sources Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections Records of the National Negro Business League Part 1: Annual Conference Proceedings and Organizational Records, 1900-1919 Part 2: Correspondence and Business Records, 1900-1923 University Publications of America A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier RECORDS OF THE NATIONAL NEGRO BUSINESS LEAGUE Part 1: Annual Conference Proceedings and Organizational Records, 1900-1919 Part 2: Correspondence and Business Records, 1900-1923 Edited by Kenneth Hamilton Guide compiled by Robert E. Lester A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the National Negro Business League [microform] / editorial advisor, Kenneth M. Hamilton. microfilm reels — (Black studies research sources) Pt. 1 filmed from the archives of Tuskegee University; pt. 2 from a supplement to the papers of Booker T. Washington in the Library of Congress. Accompanied by a 1-volume printed reel guide compiled by Robert E. Lester, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Records of the National Negro Business League. Contents: pt. 1. Annual conference proceedings and organizational records, 1900-1924 — pt. 2. Correspondence and business records, 1900-1923. ISBN 1-55655-507-5 (microfilm : pt. 1) — ISBN 1-55655-508-3 (microfilm: pt. 2) 1. National Negro Business League (U.S.)—Archives. 2. Afro- Americans—Economic conditions—Sources. 3. Afro-Americans in business—History—Sources. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with the Honorable Wilhelmina Delco

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with The Honorable Wilhelmina Delco Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Delco, Wilhelmina R. (Wilhelmina Ruth), 1929- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with The Honorable Wilhelmina Delco, Dates: May 4, 2006 Bulk Dates: 2006 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:16:09). Description: Abstract: State representative The Honorable Wilhelmina Delco (1929 - ) served ten terms in the Texas Legislature and served on more than twenty different committees. In 1991 she was appointed speaker pro tempore, the first woman and the second African American to hold the second highest position in the Texas House of Representatives. Delco was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on May 4, 2006, in Austin, Texas. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2006_090 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® On July 16, 1929, Wilhelmina R. Delco was born to Juanita and William P. Fitzgerald in Chicago, Illinois. She attended Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago where she served as president of the student body and was a member of the National Honor Society. Delco received her B.A. degree in sociology from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1950. In 1952, Delco married, had four children and relocated to Texas. As a concerned parent, Delco became an active leader in the Parent Teacher Association of her children’s school. Delco ran and was elected to the Austin Independent School District Board of Trustees in 1968, three days after the death of Dr.