Abraham Flexner Andthe Black Medical Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950

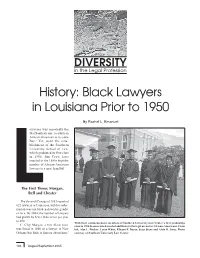

DIVERSITY in the Legal Profession History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950 By Rachel L. Emanuel ouisiana was reportedly the first Southern state to admit an African-American to its state Bar.1 Yet, until the esta- blishment of the Southern University School of Law, which graduated its first class in 1950, Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s kept the number of African-American lawyers to a mere handful. The First Three: Morgan, LBell and Chester The Seventh Census of 1853 reported 622 lawyers in Louisiana, but this infor- mation was not broken down by gender or race. By 1864, the number of lawyers had grown by fewer than seven per year to 698. With their commencement, members of Southern University Law Center’s first graduating C. Clay Morgan, a free black man, class in 1950 became much-needed additions to the legal arena for African-Americans. From was listed in 1860 as a lawyer in New left, Alex L. Pitcher, Leroy White, Ellyson F. Dyson, Jesse Stone and Alvin B. Jones. Photo Orleans but little is known about him.2 courtesy of Southern University Law Center. 104 August/September 2005 There were only four states reported to have admitted black lawyers to the bar prior to that time, none of them in the South. The states included Indiana (1860s), Maine (1844), Massachusetts (1845), New York (1848) and Ohio (1854). If, as is believed, Morgan was Louisiana’s first black lawyer,3 he would have been admitted to the Bar almost 10 years earlier than the average date for the other Southern states (Arkansas, 1866; Tennessee, 1868; Florida and Missis- sippi, 1869; Alabama, Georgia, Ken- tucky, South Carolina and Virginia, 1871; and Texas, 1873). -

Dillard University, Which Has Its Roots in Reconstruction, Has Outlasted Segregation, Discrimination and Hurricane Katrina

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Dillard 1718 ~ 2018 University was chartered on 300 June 6, 1930. TRICENTENNIAL THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION PHOTOS THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A group portrait of graduating nurses in front of Flint-Goodrich Hospital of Dillard University in 1932 Straight University in 1908, on Canal and Tonti streets Class President Nicole Tinson takes a selfie with then frst lady Michelle Obama during Dillard’s 2014 graduation. Dillard President Walter M.Kimbrough stands behind Obama. THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION New Orleans University in 1908, on St. Charles Avenue, was razed to make way for De La Salle High School. Dillard University, which has its roots in Reconstruction, has outlasted segregation, discrimination and Hurricane Katrina. THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE The university was created in 1930 from the opposition of the neighborhood. The first two historically black colleges — Straight president of the university, Will W. Alexander, University and Union Normal School — later was a white man because there were concerns named New Orleans University. that a white faculty wouldn’t want to answer The two schools were both created in 1868 to a black president. When Dillard opened its to educate newly freed African-Americans. new campus in 1935, it featured prominent fac- The schools offered professional training, in- ulty including Horace Mann Bond in psychol- The library of the new cluding in law, medicine and nursing. New ogy and education; Frederick Douglass Hall in Dillard University in 1935 Orleans University opened the Flint-Go- music; Lawrence D. -

The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central YAlE JOuRNAl OF BiOlOGY AND MEDiCiNE 84 (2011), pp.269-276. Copyright © 2011. HiSTORiCAl PERSPECTivES iN MEDiCAl EDuCATiON The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later Thomas P. Duffy, MD Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut The Flexner Report of 1910 transformed the nature and process of medical education in America with a resulting elimination of proprietary schools and the establishment of the bio - medical model as the gold standard of medical training. This transformation occurred in the aftermath of the report, which embraced scientific knowledge and its advancement as the defining ethos of a modern physician. Such an orientation had its origins in the enchant - ment with German medical education that was spurred by the exposure of American edu - cators and physicians at the turn of the century to the university medical schools of Europe. American medicine profited immeasurably from the scientific advances that this system al - lowed, but the hyper-rational system of German science created an imbalance in the art and science of medicine. A catching-up is under way to realign the professional commit - ment of the physician with a revision of medical education to achieve that purpose. In the middle of the 17th century, an cathedrals resonated with Willis’s delin - extraordinary group of scientists and natu - eation of the structure and function of the ral philosophers coalesced as the Oxford brain [1]. Circle and created a scientific revolution in the study and understanding of the brain THE HOPKINS CIRCLE and consciousness. -

THE AURORA "Let There Be Light"

KNOXVILLE COLLEGE FOUNDED 1875 THE AURORA "Let there Be Light" PUBLISHED Six TIMES A YEAR BY KNOXVILLE COLLEGE Vol. 72 KNOXVILLE COLLEGE, KNOXVILLE, TENN., DECEMBER, 1958 No,'2 ^i tm*iMMMjii*i*wti#i»wtiii#]jitii«i«nt# BULLETIN A fire which originated in a trash chute routed the residents of Wallace Hall, a dormitory for junior and senior women, ••••• Monday, December 8, shortly after nine o'clock. Damage was ••••• extensive enough to cause the removal of the group to the al ••••• ready crowded Elnathan Hall until > plans can he made con cerning the handling of the Mrs. Colston Dr. Colston 4*- growing problems of space. .o ••••• Dormitories for both wo ••••• ••••• men and men are presently ••••• ••••• under construction and are Wmti % £jririt of % (Elrmt Glpli scheduled to be ready for oc ••••• ••••• cupancy by early spring. ••••4&• 4S* 1 * I ?-fF k -Jr •**- ••••• K. C.'s Choice—First Row: Jackie Roberts, Rosemary Martin, Elaine ••••• '58 Grad Given tk Wood. Second Row: Jamesena Boyd, Shirley Lewis, Ann Vinson, Jeff ••••• N. Y. C. Post Owens; and third row: Garmon Moore, Richard Jackson, and Anthony 48* Blackburn. —Photo by Walls ••••• 48* 48* • ••«• ••••• Knoxville College Chooses Ten ••••48*• ••••• 43* 4••••»• Representatives For Who's Who ®l|e (ttdfefam*, karoos, pitlfydhttma, Heart fS- BY DESSA BLAIR Knoxville College chose ten outstanding personalities for the list ••••• 48* of who's who among students in American universities and colleges. 4* attfr |Happg ••••• The five students renamed for the school year 1958-1959 were: 48* Richard Jackson, Anthony Blackburn, Rosemary Martin, Jamesena Boyd and Elaine Wood. Richard Jackson, a senior, is member of the concert choir, NEA, endowed with great leadership Panhellenic Council, the Council qualities. -

Newsletteralumni News of the Newyork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009

NEWSLETTERAlumni News of the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009 Virginia Kneeland Frantz and 20th Century Surgical Pathology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons and the Presbyterian Hospital in the City of New York Marianne Wolff and James G. Chandler Virginia Kneeland was born on November 13, 1896 into a at the North East corner of East 70th Street and Madison Avenue. family residing in the Murray Hill district of Manhattan who also Miss Kneeland would receive her primary and secondary education owned and operated a dairy farm in Vermont.1 Her father, Yale at private schools on Manhattan’s East Side and enter Bryn Mawr Kneeland, was very successful in the grain business. Her mother, College in 1914, just 3 months after the Serbian assassination of Aus- Anna Ball Kneeland, would one day become a member of the Board tro-Hungarian, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which ignited the Great of Managers of the Presbyterian Hospital, which, at the time of her War in Europe. daughter’s birth, had been caring for the sick and injured for 24 years In November of 1896, the College of Physicians and Surgeons graduated second in their class behind Marjorie F. Murray who was (P&S) was well settled on West 59th Street, between 9th and 10th destined to become Pediatrician-in-Chief at Mary Imogene Bassett (Amsterdam) Avenues, flush with new assets and 5 years into a long- Hospital in 1928. sought affiliation with Columbia College.2 In the late 1880s, Vander- Virginia Frantz became the first woman ever to be accepted bilt family munificence had provided P&S with a new classrooms into Presbyterian Hospital’s two year surgical internship. -

2019-2021 CATALOG Knoxville College

Knoxville College 2019-2021 CATALOG KNOXVILLE COLLEGE CATALOG 2019-2021 “LET THERE BE LIGHT” Knoxville College is authorized by the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. This authorization must be renewed every year and is based on an evaluation by minimum standards concerning the quality of education, ethical business practices, health and safety, and fiscal responsibility. General Information Authorization Knoxville College is authorized by the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. This authorization must be renewed every year and is based on an evaluation by minimum standards concerning the quality of education, ethical business practices, health and safety, and fiscal responsibility. Policy Revisions Knoxville College reserves the right to make changes relating to the Catalog. A summary of any changes, including fees and other charges,course changes, and academic requirements for graduation, shall be published cumulatively in the Catalog Supplement. Said publication of changes shall be considered adequate and effective notice for all students. Detailed information on changes will be maintained in the Registrar’s Office. Each student is responsible for keeping informed of current graduation requirements in the appropriate degree program. Equal Opportunity Commitment Knoxville College is committed to providing equal opportunity for all qualifi ed persons. It does not discriminate on the basis of race,color, national or ethnic origin, gender, marital status, or handicap in the administration of its educational and admissions policies, financial affairs, employment policies and programs, student life and services, or any other collegeadministered program. Address: Knoxville College P.O. Box 52648 Knoxville, TN 37950-2648 Telephone: (865) 521-8064 Fax: (865) 521-8068 Website: www.knoxvillecollege.edu Table of Contents A Message From The Interim President ............................................................. -

Ed 316 156 Author Title Institution Pub Date

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 316 156 HE 023 281 AUTHOR Fordyce, Hugh R.; Kirschner, Alan H. TITLE 1989 Statistical Report. INSTITUTION United Negro College Fund, Inc., New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 85p. AVAILABLE FROM United Negro College Fund, 500 East 62nd St., New York, NY 10021. PUB TYPE Statistical Data (110) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Black Colleges; Black Education; College Admission; College Faculty; Degrees (Academic); *Educational Finance; Endowment Funds; *Enrollment Trends; Higher Education; Minority Groups; Student Characteristics IDENTIFIERS *United Negro College Fund ABSTRACT The report is an annual update of statistical information about the 42 member institutions of the United Negro College Fund, Inc. (UNCF). Information is provided on enrollment, admissions, faculty, degrees, financial aid, college costs, institutional finances, and endowment. Highlights identified include: the fall 1989 total enrollment was a 10% rise over 1987 and 13% over 1986; 42% of the total enrollment was male; 42% of the enrollment was classified as freshman; Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina were the leading states in regard to the home residence of UNCF students; 45% of the freshmen applicants admitted to UNCF colleges become enrolled students; almost 50% of full-time faculty possessed a doctoral degree; the average full professor at a UNCF college earned $28,443; the total number of degrees awarded (5,728) was 2% more than in the previous year; and the value of endowment funds in June 1988 ($13 million) more than doubled in the past 6 years. Thirteen tables or figures provide detailed statistics. Sample topics of the 29 appendices include full-time and part-time enrollment, enrollment by sex, faculty by race and degrees, faculty turnover and tenure, degrees conferred by major, institutional costs, revenues and expenditures, total endowment, and UNCF member colleges. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

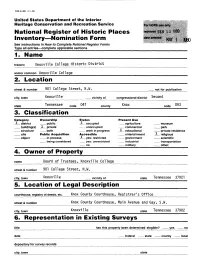

FHR-&-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________________ 1. Name__________________ historic Knoxville College Historic District___________ and/or common Knoxville College__________________ 2. Location______________ street & number 901 College Street, N.W, not for publication city, town Knoxville vicinity of congressional district Second state Tennessee code 047 county Knox code 093 3. Classification Cat.egory Ownership Status Present Use X district public A occuoied agriculture museum building(s) X private _ unoccupied commercial park structure both work in oroaress X educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object in process X ves: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Board of Trustees, Knoxville College street & number 901 College Street, N.W. city, town Knoxville vicinity of state Tennessee 37921 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Knox County Courthouse, Registrar's Office street & number Knox County Courthouse, Main Avenue and Gay, S.W. city, town Knoxville state Tennessee 37902 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title has this property been determined elegible? __ yes no date federal __ state __ county __ local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date X fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Knoxville College Historic District is located on the Knoxville, Tennessee hilltop campus of Knoxville College, two miles northwest of the Knox County Courthouse. -

Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?

Washington University Law Review Volume 59 Issue 3 Legal Education January 1981 Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education? Robert M. Hardaway University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Robert M. Hardaway, Legal and Medical Education Compared: Is It Time for a Flexner Report on Legal Education?, 59 WASH. U. L. Q. 687 (1981). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol59/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEGAL AND MEDICAL EDUCATION COMPARED: IS IT TIME FOR A FLEXNER REPORT ON LEGAL EDUCATION? ROBERT M. HARDAWAY* I. INTRODUCTION In 1907, medical education in the United States was faced with many of the problems' that critics feel are confronting legal education today:3 an over-production of practitioners, 2 high student-faculty ratios, proliferation of professional schools, insufficient financing,4 and inade- * Assistant Professor, University of Denver College of Law. B.A., 1966, Amherst College; J.D., 1971, New York University. The author wishes to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Heather Stengel, a third year student at the University of Denver College of Law, in the prepara- tion of this article and the tabulation of statistical data. -

Medical School Expansion in the 21St Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine

Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. September 2015 Cover: University of New England campus Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. FOREWORD The Macy Foundation has recently documented the motivating factors, major challenges, and planning strategies for the fifteen new allopathic medical schools (leading to the M.D. degree) that enrolled their charter classes between 2009 and 2014.1,2 A parallel trend in the opening of new osteopathic medical schools (leading to the D.O. degree) began in 2003. This expansion will result in a greater proportional increase in the D.O. workforce than will occur in the M.D. workforce as a result of the allopathic expansion. With eleven new osteopathic schools and nine new sites or branches for existing osteopathic schools, there will be more than a doubling of the D.O. graduates in the U.S. by the end of this decade. Douglas Wood, D.O., Ph.D., and Michael Whitcomb, M.D., bring their broad experiences in D.O. and M.D. education to this report of the osteopathic school expansion. They identify ways in which the new schools are similar to and different from the existing osteopathic schools, and they identify differences in the rationale and characteristics of the new osteopathic schools, compared with those of the new allopathic schools that Dr. Whitcomb has previously chronicled. 1 Whitcomb ME. -

US Medical Education Reformers Abraham Flexner (1866-1959) and Simon Flexner (1863-1946)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 443 765 SO 031 860 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE U.S. Medical Education Reformers Abraham Flexner (1866-1959) and Simon Flexner (1863-1946). PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 12p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; *Educational Change; *Educational History; Higher Education; *Medical Education; *Professional Recognition; *Social History IDENTIFIERS *Flexner (Abraham); Johns Hopkins University MD; Reform Efforts ABSTRACT This paper (in the form of a dialogue) tells the stories of two members of a remarkable family of nine children, the Flexners of Louisville, Kentucky. The paper focuses on Abraham and Simon, who were reformers in the field of medical education in the United States. The dialogue takes Abraham Flexner through his undergraduate education at Johns Hopkins University, his founding of a school that specialized in educating wealthy (but underachieving) boys, and his marriage to Anne Laziere Crawford. Abraham and his colleague, Henry S. Pritchett, traveled around the country assessing 155 medical schools in hopes of professionalizing medical education. The travels culminated in a report on "Medical Education in the United States and Canada" (1910). Abraham capped his career by creating the first significant "think tank," the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. The paper also profiles Simon Flexner, a pharmacist whose dream was to become a pathologist. Simon, too, gravitated to Johns Hopkins University where he became chief pathologist and wrote over 200 pathology and bacteriology reports between 1890-1909. He also helped organize the Peking Union Medical College in Peking, China, and was appointed Eastman Professor at Oxford University.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

The Flexner Report: 100 Years Later

International Journal of Medical Education. 2010; 1:74-75 Letter ISSN: 2042-6372 DOI: 10.5116/ijme.4cb4.85c8 The Flexner report: 100 years later Douglas Page, Adrian Baranchuk Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Correspondence: Adrian Baranchuk, Department of Cardiology, Kingston General Hospital, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, Email: [email protected] Accepted: October 12, 2010 One hundred years ago, medical education in the US and Following Flexner’s recommendations, accreditation Canada was very different than it is today. There was little programs and a shift in resources led to the closure of standardization regulating how medical education was many of the medical schools in existence at that time. delivered, and there was wide variation in the aptitude of Medical training became much more centralized, with practicing physicians. Though some medical education was smaller rural schools closing down as resources were delivered by the universities, many non-university affiliated concentrated in larger Universities that had better training schools still existed. Besides scientific medicine, homeo- facilities. Proprietary schools were terminated, and medi- pathic, osteopathic, chiropractic, botanical, eclectic, and cal education was delivered with the philosophy that basic physiomedical medicine were all taught and practiced by sciences and clinical experience were paramount to pro- different medical doctors at that time. In addition, there ducing effective physicians.2