Internationalization of Indian Enterprises: Patterns, Determinants and Policy Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is the Vice Chairman and Managing

Mr Jayadev Galla Vice-Chairman Amara Raja Group Mr Jayadev Galla (Jay) is the Vice Chairman and Managing Director of Amara Raja Batteries Limited (ARBL), a leading manufacturer of Advanced Lead Acid batteries for Industrial and Automotive applications. ARBL is a joint venture between Amara Raja group and US based Johnson Controls Inc. (JCI). JCI is a USD 35 billion conglomerate and the global leader in building efficiency, automotive interior experience and automotive power solutions. The company owns the brand name “Amaron” which is the second largest selling automotive battery brand in India today. ARBL is a widely held public limited company listed on the National Stock Exchange of India Limited and the Bombay Stock Exchange Limited. The gross revenue for the year ending March 31, 2012 is more than USD 450 mn. Achievements Spearheading ARBL’s automotive batteries (Amaron) venture Striking a partnership with JCI, U.S.A. for the automotive battery business Winning the prestigious Ford World Excellence Award in 2004 achieved by meeting global delivery standards. ARBL is the 3rd supplier from India to be given this award. Posts and Responsibilities Confederation of Indian Industry Young Indians National Branding Chair Young Indian’s National Immediate Past Chairman Young Indians Immediate Past Chairman - District Chapter Initiatives Amara Raja Group of Companies Vice Chairman, Amara Raja Power Systems Limited Vice Chairman and Managing Director, Amara Raja Electronics Limited Vice Chairman, Mangal Industries Limited Director, Amara Raja Infra Private Limited Director, Amaron Batteries (P) Ltd. Director, Amara Raja Industrial Services (P) Ltd. Permanent Trustee of the Rajanna Trust The Trust was established in 1999 and is dedicated to rural development and to improve the economic conditions of the farmers in Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh. -

Pitchbook US Template

Investor Presentation Business Overview October 2019 0 DISCLAIMER All statements, graphics, data, tables, charts, logos, names, figures and all other statements relating to future results of operation, financial condition, business information (“Contents”) contained in this document (“Material”) is prepared by GMR prospects, plans and objectives, are based on the current beliefs, assumptions, Infrastructure Limited (“Company”) soley for the purpose of this Material and not expectations, estimates, and projections of the directors and management of the otherwise. This Material is prepared as on the date mentioned herein which is solely Company about the business, industry and markets in which the Company and the intended for reporting the developments of the Company to the investors of equity GMR Group operates and such statements are not guarantees of future shares in the Company as on such date, the Contents of which are subject to performance, and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other change without any prior notice. The Material is based upon information that we factors, some of which are beyond the Company’s or the GMR Group’s control and consider reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete. difficult to predict, that could cause actual results, performance or achievements to differ materially from those in the forward looking statements. Such statements are Neither the Company, its subsidiaries and associate companies (“GMR Group”), nor not, and should not be construed, as a representation as to future performance or any director, member, manager, officer, advisor, auditor and other persons achievements of the Company or the GMR Group. -

GM R Infrastructure Limited Corporate Office: New Udaan Bhawan, Ground Floor Opp

GM R Infrastructure Limited Corporate Office: New Udaan Bhawan, Ground Floor Opp. Terminal 3, IGI Airport New Delhi 110037, India CIN L45203MH1996PLC281138 T +911147197001 F +911147197181 w www.gmrgroup.in November 15, 2018 To, BSE Limited, National Stock Exchange of India Limited, Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Dalal Street, Plot no. C/1, G Block, Mumbai- 400 001 Bandra-Kurla Complex Bandra (E), Mumbai - 400 051 Dear Sir/ Madam, Sub: Investor Presentation Ref: Our letter dated November 14, 2018 regarding schedule of conference call with investors I analysts With reference to above , we enclose herewith investor presentation for the Q2 FY 2019 Results. This is for your information and records. Thanking you, for GMR Infrastructure Limited I I {ry .~.--r~ •/ .; T. Ven <at amana Compan Secretary & Compliance Officer Registered Office: Naman Centre, 7th Floor Opp. Dena Bank, Plot No. C-31 G Block, Bandra Kurla Complex Bandra (East), Mumbai Airports 1 Energy 1 Transportation 1 Urban Infrastructure 1 Foundation Maharashtra, India- 400051 Investor Presentation Q2FY2019 0 DISCLAIMER All statements, graphics, data, tables, charts, logos, names, figures and all other statements relating to future results of operation, financial condition, business information (“Contents”) contained in this document (“Material”) is prepared by GMR prospects, plans and objectives, are based on the current beliefs, assumptions, Infrastructure Limited (“Company”) soley for the purpose of this Material and not expectations, estimates, and projections of the directors and management of the otherwise. This Material is prepared as on the date mentioned herein which is solely Company about the business, industry and markets in which the Company and the intended for reporting the developments of the Company to the investors of equity GMR Group operates and such statements are not guarantees of future shares in the Company as on such date, the Contents of which are subject to performance, and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other change without any prior notice. -

Download This Publication

b685_Chapter-06.qxd 12/30/2008 2:21 PM Page 135 Published in Indian Economic Superpower: Fiction or Future? Edited by Jayashankar M. Swaminathan World Scientific Publishing Company: 2009 CHAPTER 6 INDIA’S AVIATION SECTOR: DYNAMIC TRANSFORMATION John Kasarda* and Rambabu Vankayalapati† Introduction India is no longer a country of promise — it has arrived, and in a big way. Not long ago regarded as a relatively closed and staid demographic giant, the nation has emerged over the past decade as “open for business,” quickly joining global leaders in everything from IT and BPO to financial services and medical tourism. As India’s integration into the global economy accelerated, so did its annual GDP growth rate, averaging over 8% since 2003. In the fiscal year 2007, its GDP expanded by 9.4% and was forecasted to remain above 9% for the next three years.40 Foreign investment concurrently mushroomed, posi- tioning India as number two in the world (behind China) as the preferred location for FDI. Net capital inflows (FDI plus long-term commercial debt) exceeded USD24 billion. The country’s explosive economic growth has yielded a burgeoning middle class in which higher incomes have led to sharp rises in purchases of automobiles, motorbikes, computers, mobile phones, TVs, refrigerators, and branded con- sumer goods of all types. Rapidly rising household incomes have also generated a burst in air travel, both domestic and international. In just three years from 2003–2004 to 2006–2007, commercial aircraft enplanements in India rose from 48.8 million to nearly 90 million, a growth rate of almost 25% annually. -

Accelerating Infrastructure Investment Facility in India–GMR Hyderabad

Environment and Social Due Diligence Report January 2014 IND: Accelerating Infrastructure Investment Facility in India –GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited Prepared by India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited for the Asian Development Bank This report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environment and Social Due Diligence Report GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited IIFCL Due diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Sub Project: Development, design, construction, operation and maintenance of Greenfield international airport at Shamshabad, near Hyderabad in Andhra Pradesh Sub-Project Developer: GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited January 2014 1 Environment and Social Due Diligence Report GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited Sub Project: Development, design, construction, operation and maintenance of Greenfield international airport at Shamshabad, near Hyderabad in Andhra Pradesh Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards 2 Environment and Social Due Diligence Report GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited CONTENTS PROJECT BACKGROUND: ..................................................................................................... -

PHDCCI MANAGING COMMITTEE for 2019-20 LEADERSHIP 1. Dr

PHDCCI MANAGING COMMITTEE FOR 2019-20 LEADERSHIP 1. Dr. D K Aggarwal : President 2. Shri Sanjay Aggarwal : Senior Vice President 3. Shri Pradeep Multani : Vice President 4. Shri Rajeev Talwar : Immediate Former President PATRON MEMBERS 1. Shri Vikram Agarwal : Prakash Industries Ltd. 2. Shri Ramesh Kumar Agarwal : Agarwal Packers and Movers Limited 3. Shri Shekhar Agarwal : Maral Overseas Ltd. 4. Shri Himanshu Agarwal : Zydex Industries Pvt. Ltd. 5. Shri Sanjay Aggarwal : Paramount Communications Ltd. 6. Shri Govind Aggarwal : Basant Projects Limited (Unity Group) 7. Ms. Nidhi Ahuja : Ahujasons Shawlwale Pvt. Ltd. 8. Shri Sandeep Arya : Amtrak Technologies Private Limited 9. Shri Akhil Bansal : KPMG India 10. Shri Gautam Bali : Vestige Marketing Pvt. Ltd. 11. Shri Manoj Barthwal : Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd. 12. Shri Nishant V. Berlia : Apeejay Stya & Svran Group (Martin & Harris Laboratories Ltd.) 13. Shri Uma Shankar Bhartia : India Glycols Limited 14. Shri Sudhangshu S. Biswal : Omaxe Limited 15. Shri Anil Kumar Chopra : Dewan P. N. Chopra & Co. 16. Shri Vishal Sharma : Dalmia Cement (Bharat) Limited 17. Shri Rajesh Kumar Gupta : Dharampal Satyapal Limited 18. Shri Rajesh Gupta : Multicolor Steels (India) Pvt. Ltd. 19. Shri Sudhir Hoshing : IRB Infrastructure Developers Ltd. 20. Shri Subodh Kumar Jain : South Asia Gas Enterprise Pvt. Ltd. 21. Ms. Pooja Jain Gupta : Luxor Writing Instruments Pvt. Ltd. 22. Shri Pradeep Kumar Jain : Parsvnath Developers Limited 23. Shri Kamlesh Kumar Jain : Varun Beverages Limited 24. Shri Saumya Vardhan Kanoria : Kanoria Chemicals & Industries Limited 25. Dr. S. C. Kansal : SMPP Private Limited 26. Shri Vikram Kapur : The Atlas Cycle (Haryana) Limited 27. Shri Vivek Katoch : Oriflame India Private Limited 28. -

Pitchbook US Template

Investor Presentation Business Overview July 2020 0 DISCLAIMER All statements, graphics, data, tables, charts, logos, names, figures and all other statements relating to future results of operation, financial condition, business information (“Contents”) contained in this document (“Material”) is prepared by GMR prospects, plans and objectives, are based on the current beliefs, assumptions, Infrastructure Limited (“Company”) soley for the purpose of this Material and not expectations, estimates, and projections of the directors and management of the otherwise. This Material is prepared as on the date mentioned herein which is solely Company about the business, industry and markets in which the Company and the intended for reporting the developments of the Company to the investors of equity GMR Group operates and such statements are not guarantees of future shares in the Company as on such date, the Contents of which are subject to performance, and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other change without any prior notice. The Material is based upon information that we factors, some of which are beyond the Company’s or the GMR Group’s control and consider reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete. difficult to predict, that could cause actual results, performance or achievements to differ materially from those in the forward looking statements. Such statements are Neither the Company, its subsidiaries and associate companies (“GMR Group”), nor not, and should not be construed, as a representation as to future performance or any director, member, manager, officer, advisor, auditor and other persons achievements of the Company or the GMR Group. -

Guiding You Through*

Guiding you through* Services for Special Economic Zones PricewaterhouseCoopers has worked closely with the Government of India during the evolution of SEZ Policy and continues to work with the Government and private sector to enable flow of resources to achieve the policy objectives. PricewaterhouseCoopers strong relationship with the Our Services specialists provide industry Central and State Tax & Regulatory Services focused tax & regulatory and Governments and have been l Structuring advisory services to help clients instrumental in bringing about l Approvals evolve a tax efficient, regulatory several significant policy l Operationalization compliant business model initiative and changes in SEZ l Compliance while managing risk and regime. maximizing shareholder value. We constantly share Advisory services Our team of professionals with knowledge with players in the l Strategy and strategic modelling diverse background and SEZ sector and the l Feasibility studies experience have worked in the Government. We also l Location & State profiling SEZ sector since the conduct research, arrange l Transaction support emergence of the omnibus work-shops and conferences l Fund raising regime in the form of SEZ Act. to deliberate upon important l Business restructuring This group is integrated across issues for the development of all our lines of services and is the industry. one-stop shop to clients for all their needs. The sharing of best practices and the transfer of knowledge is one of the greatest strengths of our firm. In order to provide best possible level of service, we invest the time of our consultants and partners in the development of our industry expertise. Our team maintains Value propositions Your requirements Our service offerings Conceptualization • Undertaking pre-feasibility study, location analysis, state profiling, costing, etc. -

Aban Offshore ABG Shipyard ACC Limited Adani Group Aditya Birla

A . Aban Offshore . Amul[8] . ABG Shipyard . Andhra Bank . ACC Limited . Apollo Hospitals[9] . Adani Group . Apollo Tyres[10] . Aditya Birla Group.[2] . Archies Greetings & Gifts Ltd[11] . Ador Powertron Limited[3] . Aptech . Aftek . Arvind Mills . Air India[4] and subsidiary Air-India Express[5] . Ashok Leyland[12] . Air Sahara[6] . Asia Motor Works . Ajanta Group . Asian Paints[13][14] . Alang Ship Recycling Yard[7] . Axis Bank . Allahabad Bank . Ambuja Cements . Amrutanjan Healthcare [edit]B . Bajaj Auto[15] . Bhushan Steel . Balaji Telefilms[16] . Biocon . Bank of India[15] . BMR Advisors[21] . Bank of Baroda[17] . Bombay Dyeing[22] . Bharat Aluminium Company[18] . BPL group[23] . Bharat Electronics Limited[19] . Ballarpur Industries Limited[24] . Bharat Forge[20] . Bharat Earth Movers Limited . Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited[15] . Britannia Industries[25] . Bharat Petroleum[15] . BirlaSoft . Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited . Bharati Shipyard . Bharti Airtel [edit]C . Camlin Ltd. Coal India Limited[31] . CMC Limited[26] . Container Corporation of India . Canara Bank[15] . Crest Animation Studios[32] . Cellebrum Technologies Limited[27] . Crompton Greaves . Central Bank of India . Cadila Healthcare[33] . CESC . Coromandel International[34] . CPCL . Catholic Syrian Bank . Cipla[28] . Cosmic Circuits . Club Mahindra Holidays[29] . Covansys India Limited[30] [edit]D . Dabur India Limited[35] . Dr. Reddy's . Damodar Valley Corporation[36] Laboratories[40] . Deccan Aviation Pvt. Ltd.[37][38] is an aviation company that operates Air . DLF Universal Limited Deccan . Directi . Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Limited[39] [edit]E . Educomp Solutions . Essar Group[44] . Eicher Motors[41] . Eureka Forbes . Engineers India Limited[42] . EID Parry . English Indian Clays Limited[43] . Evalueserve[45] . Escorts Group . -

Top 50 Family Business Leaders

Saad Abdullah Al-Khorayef Erramon Aboitiz Johan Andresen Gianluigi Aponte Simone Bagel-Trah Marcelo Bahia Odebrecht Anthony Bamford Mauro Gilberto Bellini Alessandro Benetton Jean Burelle Anand Burman Marilyn Carlson Nelson Adriana Cisneros Marie-Christine Coisne-Roquette Tim Cooper Jean-Charles & Jean-François Decaux Axel Dumas Richard Eu Ferruccio Ferragamo Antoine Fiévet Bill Ford Wolfram Freudenberg Adi Godrej Nick Hayek Abigail Johnson Lim Kok Thay William Lauder Nicola Leibinger-Kammüller Isolde & Willi Liebherr Jean Mane Antonio & Emma Marcegaglia José Mas Eliodoro Matte Larraín Liz Mohn Pawan Munjal Hans Georg Näder Rajan Nanda Abdallah Obeikan Enrique Pescarmona Grandhi Mallikarjuna Rao Güler Sabanci Lino Saputo Jr Oliver Scholz Atul Shah Steve Sheetz Luiza Helena Trajano Inácio Rodrigues Arunachalam Vellayan Mikkel Vestergaard Frandsen Manfred Wittenstein Francis Yeoh Saad Abdullah Al-Khorayef Erramon Aboitiz Johan Andresen Gianluigi Aponte Simone Bagel-Trah Marcelo Bahia Odebrecht Anthony Bamford Mauro Gilberto Bellini Alessandro Benetton Jean Burelle Anand Burman Marilyn Carlson Nelson Adriana Cisneros Marie-Christine Coisne-Roquette Tim Cooper Jean-Charles & Jean-François Decaux Axel Dumas Richard Eu Ferruccio Ferragamo Antoine Fiévet Bill Ford Wolfram Freudenberg Adi Godrej Nick Hayek Abigail Johnson Lim Kok Thay William Lauder Nicola Leibinger-Kammüller Isolde & Willi Liebherr Jean Mane Antonio & Emma Marcegaglia José Mas Eliodoro Matte Larraín Liz Mohn Pawan Munjal Hans Georg Näder Rajan Nanda Abdallah Obeikan Enrique Pescarmona -

Delhi Airport

Investor Presentation FY2018 0 DISCLAIMER All statements, graphics, data, tables, charts, logos, names, figures and all other statements relating to future results of operation, financial condition, business information (“Contents”) contained in this document (“Material”) is prepared by GMR prospects, plans and objectives, are based on the current beliefs, assumptions, Infrastructure Limited (“Company”) soley for the purpose of this Material and not expectations, estimates, and projections of the directors and management of the otherwise. This Material is prepared as on the date mentioned herein which is solely Company about the business, industry and markets in which the Company and the intended for reporting the developments of the Company to the investors of equity GMR Group operates and such statements are not guarantees of future shares in the Company as on such date, the Contents of which are subject to performance, and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other change without any prior notice. The Material is based upon information that we factors, some of which are beyond the Company’s or the GMR Group’s control and consider reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete. difficult to predict, that could cause actual results, performance or achievements to differ materially from those in the forward looking statements. Such statements are Neither the Company, its subsidiaries and associate companies (“GMR Group”), nor not, and should not be construed, as a representation as to future performance or any director, member, manager, officer, advisor, auditor and other persons achievements of the Company or the GMR Group. In particular, such statements (“Representatives”) of the Company or the GMR Group provide any representation should not be regarded as a projection of future performance of the Company or the or warranties as to the correctness, accuracy or completeness of the Contents and GMR Group. -

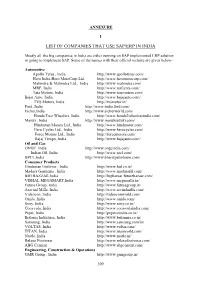

List of Companies That Use Sap/Erp in India

ANNEXURE I LIST OF COMPANIES THAT USE SAP/ERP IN INDIA Mostly all the big companies in India are either running on SAP implemented ERP solution or going to implement SAP. Some of the names with their official website are given below- Automotive Apollo Tyres , India http://www.apollotyres.com/ Hero India-Hero MotoCorp Ltd. http://www.heromotocorp.com/ Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd., India http://www.mahindra.com/ MRF, India http://www.mrftyres.com/ Tata Motors, India http://www.tatamotors.com/ Bajat Auto, India http://www.bajajauto.com/ TVS Motors, India http://tvsmotor.in/ Ford ,India http://www.india.ford.com/ Eicher,India http://www.eicherworld.com/ Honda Two Wheelers, India http://www.honda2wheelersindia.com/ Maruti , India http://www.marutisuzuki.com/ Hindustan Motors Ltd., India http://www.hindmotor.com/ Hero Cycles Ltd., India http://www.herocycles.com/ Force Motors Ltd., India http://forcemotors.com/ Bajaj Tempo, India http://www.bajajauto.com/ Oil and Gas ONGC India http://www.ongcindia.com/ Indian Oil, India http://www.iocl.com/ BPCL,India http://www.bharatpetroleum.com/ Consumer Products Hindustan Unilever , India http://www.hul.co.in/ Madura Garments , India http://www.madurafnl.com/ BIG BAZZAR,India http://bigbazaar.futurebazaar.com/ VISHAL MEGAMART,India http://www.megamalls.in/ Future Group, India http://www.futuregroup.in/ Aravind Mills, India http://www.arvindmills.com/ Videocon, India http://videoconworld.com/ Onida, India http://www.onida.com/ Sony, India http://www.sony.co.in/ Coca cola, India http://www.coca-colaindia.com/