HAWTHORNE-THESIS-2014.Pdf (14.05Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Late Afternoon Last June, A

FAST FOOD BY scott korb PHOTOGRAPHS BY liz barclay ne late afternoon last June, a few hands, mouth, nose, face, arms, hair, ears, and weeks before the start of Rama- feet. The clothes you wear are supposed to be dan, with an hour remaining before clean, too. The stain on his shirt was a problem. Asr, Islam’s afternoon prayer, Imam The imam had begun the day with a prayer O Khalid Latif became suddenly aware at sunrise. Soon after, accompanied by a of blood on his shirt. Even though he was friend, he’d left New York City in a van headed on the road, he knew he would have to pray for a halal meat-processing facility in western soon but was not sure that he could. Maryland known as Simply Natural, about 250 Five daily prayers constitute a pillar of miles away. By one o’clock that afternoon, the Islam, and these prayers are to be done in a men had packed the vehicle with three hand- state of ritual purity. To this end, Muslims slaughtered steers and were headed back. wash before they pray, a preparation known as “Let’s not stop,” the imam had said some- wudhu that includes careful attention to the where along the way. Latif had no change of clothes. Anticipating the logjam on the New Jersey side of the Holland Tunnel, he started calling sheikhs for advice. After two or three calls, he reached Dawood Yasin, an imam from Berke- ley, California, and an avid bow hunter familiar with the mess involved in breaking down animals. -

Broiler Chickens

The Life of: Broiler Chickens Chickens reared for meat are called broilers or broiler chickens. They originate from the jungle fowl of the Indian Subcontinent. The broiler industry has grown due to consumer demand for affordable poultry meat. Breeding for production traits and improved nutrition have been used to increase the weight of the breast muscle. Commercial broiler chickens are bred to be very fast growing in order to gain weight quickly. In their natural environment, chickens spend much of their time foraging for food. This means that they are highly motivated to perform species specific behaviours that are typical for chickens (natural behaviours), such as foraging, pecking, scratching and feather maintenance behaviours like preening and dust-bathing. Trees are used for perching at night to avoid predators. The life of chickens destined for meat production consists of two distinct phases. They are born in a hatchery and moved to a grow-out farm at 1 day-old. They remain here until they are heavy enough to be slaughtered. This document gives an overview of a typical broiler chicken’s life. The Hatchery The parent birds (breeder birds - see section at the end) used to produce meat chickens have their eggs removed and placed in an incubator. In the incubator, the eggs are kept under optimum atmosphere conditions and highly regulated temperatures. At 21 days, the chicks are ready to hatch, using their egg tooth to break out of their shell (in a natural situation, the mother would help with this). Chicks are precocial, meaning that immediately after hatching they are relatively mature and can walk around. -

Indonesian Muslim

MAJELIS ULAMA INDONESIA LEMBAGA PEMULIAAN LINGKUNGAN HIDUP DAN SUMBER DAYA ALAM WADAH MUSYAWARAH PARA ULAMA ZU’AMA DAN CENDEKIAWAN MUSLIM Jalan Dempo 19, Pegangsaan, Jakarta Pusat 10320. Telp./Fax. 021-31908367 Website : www.mui-lplhsda.org Email: [email protected] MUSLIM STATEMENT ON WILDLIFE AND ANIMAL WELFARE Hayu Prabowo Chairman of Environmental and Natural Resources Board The Indonesian Council of Ulema Allah has made known through the Qur’an and via the Prophet Mohammed (pbuh) in the Hadith that He is the creator of all life on Earth and indeed in the Universe (Qur’an 6:12; 21:19). We also know from the Qur’an that Allah has placed humanity in the role of Khalifa - Vice Regent on Earth (Qur’an 2:30; 38:26). We know that on the Day of Judgement we will have to answer before Allah as to how well we conducted ourselves as Khalifas for life on Earth (Qur’an 6:165). We know also from the Qur’an that all creatures live in community (Qur’an 6:38) and we know from the Hadith, where the Prophet Mohammed (pbuh) stopped people tormenting a mother bird by taking her young that Allah forbids the infliction of unnecessary pain and suffering on other living creatures. As Khalifas we have the right to use nature but not to abuse it. Unfortunately many animal and wildlife species are threatened with extinction. Other animals stray abandoned and hungry in the streets. On the whole, it cannot be said that we treat animals as well as we should, or carry out our responsibilities towards them. -

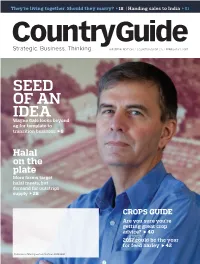

Seed of an Idea Wayne Gale Looks Beyond Ag for Template to Transition Business 8

They’re living together. Should they marry? 18 | Handing sales to India 51 western eDItIOn / COUntrY-GUIDe.CA / febrUArY 1, 2017 Seed of An IdeA Wayne Gale looks beyond ag for template to transition business 8 Halal on the plate More farms target halal meats, but demand far outstrips supply 28 CROPS GUIDE Are you sure you’re getting great crop advice? 40 2017 could be the year for feed barley 42 Publications Mail Agreement number 40069240 B:8.625” T:8.125” S:7” HATES WEEDS AS MUCH AS YOU DO. There’s nothing quite like knowing the toughest B:11.25” T:10.75” weeds in your wheat fields have met with a S:10” fitting end. Following an application of Luxxur™ herbicide, you can have peace of mind that your wild oats and toughest broadleaf perennials have gotten exactly what they deserve and will no longer be robbing your crop of its yield potential. SPRAY WITH CONFIDENCE. cropscience.bayer.ca/Luxxur 1 888-283-6847 @Bayer4CropsCA Always read and follow label directions. Luxxur™ is a trademark of the Bayer Group. R-66-01/17-10686443-E Bayer CropScience Inc. is a member of CropLife Canada. BCS10686443_Luxxur_102.indd 10686443 Insert Feb 1, 2017 Lynn.Skinner 8.125” x 10.75” Alex.Van Der Breggen 1 8.125” x 10.75” Noel.Blix -- 7” x 10” -- 100% 8.625” x 11.25” 2 Monica Van Engelen Production:Studio:Bayer:10...ls:BCS10686443_Luxxur_102.indd Bayer None Helvetica Neue LT Std, Gotham Country Guide 12-23-2016 1:18 PM None 12-23-2016 1:18 PM -- Henderson, Shane (CAL-MWG) -- Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black -- -- 6 MACHINERY Fastrac evolution Redesign keeps these tractors roadable at 70 km/h, while boosting their competitive in-field performance. -

Basic Manual for the Operation of Halal Slaughterhouse

1 2011 Muslim Mindanao Halal Certification Board,Inc. (MMHCBI) Dr. Norodin A. Kuit Halal Lead Auditor [email protected] 09263431362-tm 09296802052-sm BASIC MANUAL FOR THE OPERATION OF HALAL SLAUGHTERHOUSE 2 HALAL slaughterhouse 3 ِ ِ ِ ِ َوَََِم َن اْﻵنْ َعام ُح ُمْولَةً َوفُ ُر ًشاُكلُْوا مَّماَرَزقْ نَ ُك ُم اهللُ َوﻻَ تَ تَّبعُْوا ُخطَُوات ِ ِ 241 ال َّشْيطَان إنَّهُ لَ ُك ْم َع ُدٌّو ُمبْي ن . ) اﻵنعام- ( The Holy Qur’an Surah Al-An nam:142 says; “ And of the Cattle , are produced some are for burden(workmate, draft) and some are for food(beef, chevon, and mutton), Eat of what Allah has provided for you, and follow not the footsteps of Shaitan (Satan). Surely, he is to you an open enemy “ The Holy Bible Deuteronomy 14:3 says; “ Do not eat anything that the LORD declared unclean, you may eat these animals cattle,sheep,goat, deer, wild sheep, wild goat and antelopes- any animals have devided hooves and also chew the cud (ruminate)” 4 DEDICATION This manual is dedicated to my family ,all halal advocates who continuously strive on research, seek knowledge on halal to serve mankind and the creator Allah Subhana o wa ta ala. “And if all the trees on earth were pens and the sea(were ink where with to write ) with seven seas add to its supply, yet the Words of Allah(knowledge) would not be exhausted….” (Surah Luqman 31 : Verse 27) The Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) said: “The one who would have the worst position in Allah's sight on the Day of Resurrection would be a learned man whom people did not profit from his learning”.(Darimi). -

A Study of Problematisations in the Live Export Policy Debates

ANIMAL CRUELTY, DISCOURSE, AND POWER: A STUDY OF PROBLEMATISATIONS IN THE LIVE EXPORT POLICY DEBATES Brodie Lee Evans Bachelor of Arts (Politics, Economy, and Society; Literary Studies) Bachelor of Justice (First Class Honours) Graduate Certificate in Business (Accounting) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Queensland University of Technology 2018 School of Justice | Faculty of Law This page intentionally left blank Statement of Originality Under the Copyright Act 1968, this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing. In particular, no results or conclusions should be extracted from it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Brodie Evans QUT Verified Signature ……………………………………………………………………….. Signature October 2018 ……………………………………………………………………….. Date i Dedication For Scottie. ii Abstract Since the release of video footage exposing the treatment of animals in the live export industry in 2011, ‘animal cruelty’ has increasingly been a major concern in mainstream Australian discourse. Critiques over the inadequacy of current legal protections afforded to animals have had a significant impact on how we debate animal welfare issues and the solutions to them. -

Animal Advocacy in a Pluralist Society Submitted September 2015

Ian Starbuck School of Politics and Law PhD Thesis Title: Animal Advocacy in a Pluralist Society Submitted September 2015 Contents Introduction………………………………...………..…...…..…..1 Chapter One: Utilitarianism and Animal Advocacy…..………..13 Chapter Two: Moral Rights and Animal Advocacy….….……..36 Chapter Three: Contractarianism and Animal Advocacy…........73 Chapter Four: Animals and the Ethic of Care……...….…..……93 Chapter Five: Capabilities and Animals…………….….…...…112 Chapter Six: Animal Citizenship………………………...…….137 Chapter Seven: Multiculturalism and Animals………....……..168 Chapter Eight: Animal Advocacy and Liberalism……….……192 Conclusion……………………………………….…...…..……219 Bibliography and References………………………....………..231 Introduction Human concern with the moral status of non-human animals can be seen to stretch quite some way back into human history. In ancient Greece such concerns were considered to be very much a part of the ethical agenda, with thinkers on the issue being divided into four main schools of thought: animism; vitalism; mechanism; and anthropocentrism (Ryder 1989, chapter two). The leading light of the animist school was the renowned mathematician Pythagoras (circa 530 BC), who asserted the view that animals, like humans, were in possession of immaterial souls which, upon death, would be reincarnated in another human or animal body. In accordance with his beliefs, Pythagoras practiced kindness to animals and adhered to a vegetarian diet. Vitalism, of which perhaps the most famous exponent was Aristotle (384-322 BC), held to a belief in the interdependence of soul and body. Aristotle accepted the idea that human beings were animals, but he considered them to be at the apex of a chain of being in which the less rational existed only to serve the needs of the more rational. -

THIRD PARTY CERTIFICATION of FOOD CONTENTS 1 Introduction P1 2 Item A

24 June 2015, on behalf of Richard Sibthorpe, submission to the Senate Economics References Committee for THIRD PARTY CERTIFICATION OF FOOD CONTENTS 1 Introduction p1 2 Item a. submission p2 3 Item b. submission P3 4 Item c. submission P4 5 Item d. submission P4 6 Item e. Submission P5 7 Item f. Submission p6 8 Item g. Submission p7 9 Islam’s Jizya p8 10 My Recommendation p10 11 Conclusion p11 12 Footnotes p12 1 Introduction While this submission is formulated in accordance with the seven line items of enquiry a. to g. which is laid out by the Senate Committee, it specifically relates to the HALAL component referred to in item a. as it is associated with the Islamic religion. In Islam, halal means permitted, licit. My area of major concern is that while this halal matter is an Islamic religious and Sharia Law parameter, nevertheless it has drawn in and thereby directly effects the wider non Islamic community about Australia – yet this vast majority of Australian citizens have not been asked to participate in this Islamic religious exercise, nor do they have any say in this. In its enquiry into this subject area, it is essential that the Senate Committee does recognise and understand the direct connection between the Islamic religion with its divinely specified halal food requirement, and how this requirement directly feeds through to increased food prices for each and every non Muslim citizen in modern Australia. This is the case even though this latter majority has, as I believe, no desirability to understand or adhere to these particular requirements of the Islamic religion. -

On Shechita By: Rabbi Jeremy Rosen

More on Shechita by: Rabbi Jeremy Rosen It comes as no surprise to me that more European countries are trying to make life difficult for Jews in various ways. But how should we react? Is it worth fighting prejudice? Should this be an issue of freedom of religious practice? But then what are the boundaries? The increasing attempts to restrict Shechita (Jewish ritual slaughter) and ban circumcision are creating such a negative climate for Jews that they reinforce the strong arguments for having a homeland where we can practice our religion unimpeded. However, as with many issues of religious practice, it is not that simple, because sometimes they appear to conflict with other moral and ethical imperatives. There are those who think this is a matter for no compromise. Belgium is a strange little country where rival parties scrap over meagre rewards. It has three separate regions, five provinces, and three official languages. The parliament of French-speaking Wallonia has voted to ban ritual slaughter. Of all the major issues it has to deal with—economic, social and safety—this seems to be its priority. Now we know it is not really about cruelty to animals. Because if it were, then they would ban animal slaughter altogether (which, as my readers know, I am all in favor of, though it’s not going to happen in my lifetime). Look at the countries who have banned Shechita: Switzerland in 1893, Norway in 1930, Nazi Germany in 1933, and Sweden in 1937. None known for their love of Jews. The EU is now preparing to ban Shechita across the board unless animals are stunned, and it will require that kosher slaughtered meat be labelled as such when passed on to the wider market. -

Halal Certification in Australia and the Western World

HALAL CERTIFICATION IN AUSTRALIA AND THE WESTERN WORLD Whilst it appears that halal certication has been around for a number of years its existance was not known the majority of Australians, and possibly still is not, until towards the end of 2014 when some publicity appeared regarding it. As at the least it can have some financial impact on all Australians and as much misinformation appears on the internet about it this document has been prepared in the hope that it will help clarify the matter as seen from the perspective of one Australian. In this perspective no advantage in having halal certification can be found for the general Australian population but various disadvantages can be found, five of these disadvantages are set out below, these adverse effects are most likely to exist in the western world as well as Australia. 1. The methods used in the halal slaughter of require the cutting of the throats of animals whilst they are still living, this killing to be performed by a member of the Islam religion. In Australia it is a legal requirement that the animals be temporally stunned before their throat is cut, they can however recover from the temporary stunning before dying; such stunning does not take place in many countries. This method is distinct from that previously used in Australia where the animal was killed before being cut, and is now understood to be becoming prevelent. 2. Halal certification is different from the religious requirement which is that animals be killed in a certain fashion and that blood and certain varieties of animals not be eaten. -

(2016). Halal Stunning and Slaughter: Criteria for the Assessment of Dead Animals

Fuseini, A. , Knowles, T. G., Hadley, P. J., & Wotton, S. (2016). Halal stunning and slaughter: Criteria for the assessment of dead animals. Meat Science, 119, 132-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.04.033 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.04.033 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Elsevier at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0309174016301267. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Halal stunning and slaughter: Criteria for the assessment of dead animals. Awal Fuseinia, Toby G Knowlesa, Phil J Hadleyb, Steve B Wottona aUniversity of Bristol, School of Veterinary Science, Langford, Bristol. BS40 5DU. UK bAHDB, Creech Castle, Taunton , Somerset. TA1 2DX. UK Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract The debate surrounding the acceptability of stunning for Halal slaughter is one that is likely to linger. Compared to a couple of decades or so ago, one may argue that pre- slaughter stunning is becoming a popular practice during Halal slaughter due to the increasing number of Muslim-majority countries who continue to issue religious rulings (Fatwa) to approve the practice. -

The Debate Over Regulation of Ritual Slaughter in the Western World

Rovinsky: The Cutting Edge: The Debate Over Regulation of Ritual Slaughter +(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: 45 Cal. W. Int'l L.J. 79 2014 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Wed Jun 10 14:22:02 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0886-3210 Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2014 1 California Western International Law Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 [2014], Art. 3 THE CUTTING EDGE: THE DEBATE OVER REGULATION OF RITUAL SLAUGHTER IN THE WESTERN WORLD JEREMY A. ROVINSKY* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. ........80 II. BACKGROUND OF RITUAL SLAUGHTER ..................... 82 A. Religious Origins and Requirements of Ritual Slaughter .................................. 82 B. Underlying Philosophical Justifications for Kosher Slaughter .................................. 84 1. The Rationalefor Eating Meat in Jewish Thought........84 2. Human Responsibilities to Animals.................. 86 3. Judaism and Vegetarianism...................87 C. Arguments againstRitual Slaughter................ 88 III. LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS IN THE WESTERN WORLD RELATING TO RITUAL SLAUGHTER REGULATION ...................... 91 A. Early CulturalHostility toward Ritual Slaughter...........91 1. Switzerland ....................... 91 2. Norway and Sweden ................... 91 B. General Acceptance ofRitual Slaughter.............92 1. Germany and Poland .......................... 92 2. The United States ..................... ..... 94 * Dean, National Juris University & General Counsel, National Paralegal College. BA, American University, JD, The George Washington University.