Minority Ethnic Groups : a Nutrition Resource for Dietitians & Health Professionals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Knowledge on Selection, Sustainable

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE ON SELECTION, SUSTAINABLE UTILIZATION OF LOCAL FLORA AND FAUNA FOR FOOD BY TRIBES (PTG) OF ODISHA: A POTENTIAL RESOURCE FOR FOOD AND ENVIRONMENTAL SECURITY Prepared by SCSTRTI, Bhubaneswar, Government of Odisha Research Study on “Indigenous knowledge on selection, sustainable utilization of local flora and fauna for food by tribes I (PTG) of Odisha: A potential resource for food and environmental security” ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Research and Training Institute, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar commissioned a study, titled“Indigenous Knowledge on Selection & Sustainable Utilization of Local Flora and Fauna for Food by Tribes (PTGs) of Odisha: A Potential Resource for Food and Environmental Security”,to understand traditional knowledge system on local flora and fauna among the tribal communities of Odisha. This study tries to collect information on the preservation and consumption of different flora and fauna available in their areas during different seasons of the year for different socio-cultural and economic purposes that play important roles in their way of life. During the itinerary of the study, inclusive of other indegenious knowledge system, attempt was also made to understand the calorie intake of different PVTGs of Odisha through anthropometric measurements (height and weight).Including dietary measurement. Resource/Research persons fromCTRAN Consulting, A1-A2, 3rd Floor, Lewis Plaza, Lewis Road, BJB Nagar, Bhubaneswar-14, Odisha extended their technical support for data collection, analysis and report drafting with research inputs and guidance from Internal Research Experts of Directorate of SCSTRTI, Bhubaneswar. CTRAN Consulting and its Resource/Research personsdeserve thanks and complements. Also, thanks are due to all the Internal Experts and Researchers of SCSTRTI, especially Mrs. -

One Late Afternoon Last June, A

FAST FOOD BY scott korb PHOTOGRAPHS BY liz barclay ne late afternoon last June, a few hands, mouth, nose, face, arms, hair, ears, and weeks before the start of Rama- feet. The clothes you wear are supposed to be dan, with an hour remaining before clean, too. The stain on his shirt was a problem. Asr, Islam’s afternoon prayer, Imam The imam had begun the day with a prayer O Khalid Latif became suddenly aware at sunrise. Soon after, accompanied by a of blood on his shirt. Even though he was friend, he’d left New York City in a van headed on the road, he knew he would have to pray for a halal meat-processing facility in western soon but was not sure that he could. Maryland known as Simply Natural, about 250 Five daily prayers constitute a pillar of miles away. By one o’clock that afternoon, the Islam, and these prayers are to be done in a men had packed the vehicle with three hand- state of ritual purity. To this end, Muslims slaughtered steers and were headed back. wash before they pray, a preparation known as “Let’s not stop,” the imam had said some- wudhu that includes careful attention to the where along the way. Latif had no change of clothes. Anticipating the logjam on the New Jersey side of the Holland Tunnel, he started calling sheikhs for advice. After two or three calls, he reached Dawood Yasin, an imam from Berke- ley, California, and an avid bow hunter familiar with the mess involved in breaking down animals. -

Guidance Note on Safety and Quality of Traditional Milk Products

Guidance Note No. 14/2020 Guidance Note on Safety and Quality of Traditional Milk Products Summary This Document intends to help Food Businesses ensure hygiene and sanitation in manufacturing and sale of milk products particularly sweets. It focuses on enhanced declaration by sellers [Shelf Life, made of ghee/vanaspati], guide test for detection of adulteration, quality assessment by observation of flavours, body texture, colour and appearance etc. It also contains suggestions for addressing adulteration and ensuring effective regulatory compliance. This document is also expected to enhance consumer awareness about safety related aspects of traditional sweets, quick home tests and grievance redressal. Key Takeaways a. Ensure hygiene and sanitation in preparation and sale of sweets as well as other regulatory compliances including display of shelf life of pre-packaged as well as non-packaged milk products for consumer information. b. Ascertain the freshness and probability of adulteration by observing the colour, texture and flavour of milk products. There are simple tests to identify adulteration in milk products. c. Regular surveillance and enforcement activities on sweets by regulatory authorities. This Guidance Note has been prepared by Mr Parveen Jargar, Joint Director at FSSAI based on FSSAI resources including Regulations, Standards and DART Book. This note contains information collected and compiled by the author from various sources and does not have any force of law. Errors and omissions, if any can be kindly brought to our notice. Guidance Note on Milk Products Introduction India has a rich tradition of sweets with a variety of taste, texture and ingredients. Traditional milk-based sweets are generally prepared from khoya, chhena, sugar and other ingredients such as maida, flavours and colours e.g. -

Broiler Chickens

The Life of: Broiler Chickens Chickens reared for meat are called broilers or broiler chickens. They originate from the jungle fowl of the Indian Subcontinent. The broiler industry has grown due to consumer demand for affordable poultry meat. Breeding for production traits and improved nutrition have been used to increase the weight of the breast muscle. Commercial broiler chickens are bred to be very fast growing in order to gain weight quickly. In their natural environment, chickens spend much of their time foraging for food. This means that they are highly motivated to perform species specific behaviours that are typical for chickens (natural behaviours), such as foraging, pecking, scratching and feather maintenance behaviours like preening and dust-bathing. Trees are used for perching at night to avoid predators. The life of chickens destined for meat production consists of two distinct phases. They are born in a hatchery and moved to a grow-out farm at 1 day-old. They remain here until they are heavy enough to be slaughtered. This document gives an overview of a typical broiler chicken’s life. The Hatchery The parent birds (breeder birds - see section at the end) used to produce meat chickens have their eggs removed and placed in an incubator. In the incubator, the eggs are kept under optimum atmosphere conditions and highly regulated temperatures. At 21 days, the chicks are ready to hatch, using their egg tooth to break out of their shell (in a natural situation, the mother would help with this). Chicks are precocial, meaning that immediately after hatching they are relatively mature and can walk around. -

Indonesian Muslim

MAJELIS ULAMA INDONESIA LEMBAGA PEMULIAAN LINGKUNGAN HIDUP DAN SUMBER DAYA ALAM WADAH MUSYAWARAH PARA ULAMA ZU’AMA DAN CENDEKIAWAN MUSLIM Jalan Dempo 19, Pegangsaan, Jakarta Pusat 10320. Telp./Fax. 021-31908367 Website : www.mui-lplhsda.org Email: [email protected] MUSLIM STATEMENT ON WILDLIFE AND ANIMAL WELFARE Hayu Prabowo Chairman of Environmental and Natural Resources Board The Indonesian Council of Ulema Allah has made known through the Qur’an and via the Prophet Mohammed (pbuh) in the Hadith that He is the creator of all life on Earth and indeed in the Universe (Qur’an 6:12; 21:19). We also know from the Qur’an that Allah has placed humanity in the role of Khalifa - Vice Regent on Earth (Qur’an 2:30; 38:26). We know that on the Day of Judgement we will have to answer before Allah as to how well we conducted ourselves as Khalifas for life on Earth (Qur’an 6:165). We know also from the Qur’an that all creatures live in community (Qur’an 6:38) and we know from the Hadith, where the Prophet Mohammed (pbuh) stopped people tormenting a mother bird by taking her young that Allah forbids the infliction of unnecessary pain and suffering on other living creatures. As Khalifas we have the right to use nature but not to abuse it. Unfortunately many animal and wildlife species are threatened with extinction. Other animals stray abandoned and hungry in the streets. On the whole, it cannot be said that we treat animals as well as we should, or carry out our responsibilities towards them. -

The Best 25 the Best of the Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 Years in Each Category for Each Country

1995-2020 The Best 25 The Best of The Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 years in each category for each country It includes a selection of the Best from two previous anniversary events - 12 years at Frankfurt Old Opera House - 20 years at Frankfurt Book Fair Theater - 25 years will be celebrated in Paris June 3-7 and China November 1-4 ALL past Best in the World are welcome at our events. The list below is a shortlist with a limited selection of excellent books mostly still available. Some have updated new editions. There is only one book per country in each category Countries Total = 106 Algeria to Zimbabwe 96 UN members, 6 Regions, 4 International organizations = Total 106 TRENDS THE CONTINENTS SHIFT The Best in the World By continents 1995-2019 1995-2009 France ........................11% .............. 13% ........... -2 Other Europe ..............38% ............. 44% ..........- 6 China .........................8% ............... 3% .......... + 5 Other Asia Pacific .......20% ............. 15% ......... + 5 Latin America .............11% ............... 5% .......... + 6 Anglo America ..............9% ............... 18% ...........- 9 Africa .......................... 3 ...................2 ........... + 1 Total _______________ 100% _______100% ______ The shift 2009-2019 in the Best in the World is clear, from the West to the East, from the North to the South. It reflects the investments in quality for the new middle class that buys cookbooks. The middle class is stagnating at best in the West and North, while rising fast in the East and South. Today 85% of the world middleclass is in Asia. Do read Factfulness by Hans Rosling, “a hopeful book about the potential for human progress” says President Barack Obama. -

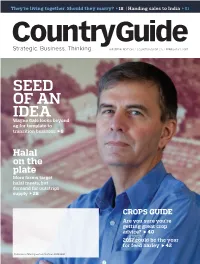

Seed of an Idea Wayne Gale Looks Beyond Ag for Template to Transition Business 8

They’re living together. Should they marry? 18 | Handing sales to India 51 western eDItIOn / COUntrY-GUIDe.CA / febrUArY 1, 2017 Seed of An IdeA Wayne Gale looks beyond ag for template to transition business 8 Halal on the plate More farms target halal meats, but demand far outstrips supply 28 CROPS GUIDE Are you sure you’re getting great crop advice? 40 2017 could be the year for feed barley 42 Publications Mail Agreement number 40069240 B:8.625” T:8.125” S:7” HATES WEEDS AS MUCH AS YOU DO. There’s nothing quite like knowing the toughest B:11.25” T:10.75” weeds in your wheat fields have met with a S:10” fitting end. Following an application of Luxxur™ herbicide, you can have peace of mind that your wild oats and toughest broadleaf perennials have gotten exactly what they deserve and will no longer be robbing your crop of its yield potential. SPRAY WITH CONFIDENCE. cropscience.bayer.ca/Luxxur 1 888-283-6847 @Bayer4CropsCA Always read and follow label directions. Luxxur™ is a trademark of the Bayer Group. R-66-01/17-10686443-E Bayer CropScience Inc. is a member of CropLife Canada. BCS10686443_Luxxur_102.indd 10686443 Insert Feb 1, 2017 Lynn.Skinner 8.125” x 10.75” Alex.Van Der Breggen 1 8.125” x 10.75” Noel.Blix -- 7” x 10” -- 100% 8.625” x 11.25” 2 Monica Van Engelen Production:Studio:Bayer:10...ls:BCS10686443_Luxxur_102.indd Bayer None Helvetica Neue LT Std, Gotham Country Guide 12-23-2016 1:18 PM None 12-23-2016 1:18 PM -- Henderson, Shane (CAL-MWG) -- Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black -- -- 6 MACHINERY Fastrac evolution Redesign keeps these tractors roadable at 70 km/h, while boosting their competitive in-field performance. -

Unit: 01 Basic Ingredients

Bakery Management BHM –704DT UNIT: 01 BASIC INGREDIENTS STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Sugar 1.4 Shortenings 1.5 Eggs 1.6 Wheat and flours 1.7 Milk and milk products 1.8 Yeast 1.9 Chemical leavening agents 1.10 Salt 1.11 Spices 1.12 Flavorings 1.13 Cocoa and Chocolate 1.14 Fruits and Nuts 1.15 Professional bakery equipment and tools 1.16 Production Factors 1.17 Staling and Spoilage 1.18 Summary 1.19 Glossary 1.20 Reference/Bibliography 1.21 Suggested Readings 1.22 Terminal Questions 1.1 INTRODUCTION Bakery ingredients have been used since ancient times and are of utmost importance these days as perhaps nothing can be baked without them. They are available in wide varieties and their preferences may vary according to the regional demands. Easy access of global information and exposure of various bakery products has increased the demand for bakery ingredients. Baking ingredients offer several advantages such as reduced costs, volume enhancement, better texture, colour, and flavour enhancement. For example, ingredients such enzymes improve protein solubility and reduce bitterness in end products, making enzymes one of the most preferred ingredients in the baking industry. Every ingredient in a recipe has a specific purpose. It's also important to know how to mix or combine the ingredients properly, which is why baking is sometimes referred to as a science. There are reactions in baking that are critical to a recipe turning out correctly. Even some small amount of variation can dramatically change the result. Whether its breads or cake, each ingredient plays a part. -

Microwave Oven

RECIPE MANUAL MICROWAVE OVEN MC3286BPUM P/NO : MFL67281868 (00) Various Cook Functions............................................................................... 3 301 Recipes List ........................................................................................... 4 Diet Fry/Low Calorie .................................................................................... 8 Tandoor se/ Kids’ Delight ............................................................................ 40 Indian Roti Basket ........................................................................................ 59 Indian Cuisine ............................................................................................... 71 Pasterurize Milk/Tea/Dairy Delight .............................................................. 101 Cooking Aid/Steam Clean/Dosa/Ghee ........................................................ 107 Usage of Accessories/Utensils ................................................................... 116 2 Various Cook Functions Please follow the given steps to operate cook functions (Diet Fry/Low Calorie, Tandoor Se/Kids’ Delight, Indian Roti Basket, Indian Cuisine, Pasteurize Milk/Tea/Dairy Delight, Cooking Aid/Steam Clean/Dosa/Ghee) in your Microwave. Cook Diet Fry/ Tandoor Indian Indian Pasteurize Cooking Functions Low Se/Kids’ Roti Cuisine Milk/Tea Aid/Steam Calorie Delight Basket /Dairy Clean/ Delight Dosa/Ghee STEP-1 Press Press Press Press Press Press STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STEP-2 Press -

'The Most Cosmopolitan Island Under the Sun'

‘The Most Cosmopolitan Island under the Sun’? Negotiating Ethnicity and Nationhood in Everyday Mauritius Reena Jane Dobson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney December 2009 The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Reena Dobson Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my grandmother, my Nani, whose life could not have been more different from my own. I will always be grateful that I was able to grow up knowing her. I also dedicate this thesis to my parents, whose interest, support and encouragement never wavered, and who were always there to share stories and memories and to help make the roots clearer. Acknowledgements At the tail end of a thesis journey which has involved entangled routes and roots, I would like to express my deepest and most heartfelt thanks to my wonderful partner, Simon White, who has been living the journey with me. His passionate approach to life has been a constant inspiration. He introduced me to good music, he reminded me to breathe, he tiptoed tactfully around as I sat in writing mode, he made me laugh when I wanted to cry, and he celebrated every writing victory – large and small – with me. I am deeply indebted to my brilliant supervisors, Associate Professor Greg Noble, Dr Zoë Sofoulis and Associate Professor Brett Neilson, who have always been ready with intellectual encouragement and inspiring advice. -

Basic Manual for the Operation of Halal Slaughterhouse

1 2011 Muslim Mindanao Halal Certification Board,Inc. (MMHCBI) Dr. Norodin A. Kuit Halal Lead Auditor [email protected] 09263431362-tm 09296802052-sm BASIC MANUAL FOR THE OPERATION OF HALAL SLAUGHTERHOUSE 2 HALAL slaughterhouse 3 ِ ِ ِ ِ َوَََِم َن اْﻵنْ َعام ُح ُمْولَةً َوفُ ُر ًشاُكلُْوا مَّماَرَزقْ نَ ُك ُم اهللُ َوﻻَ تَ تَّبعُْوا ُخطَُوات ِ ِ 241 ال َّشْيطَان إنَّهُ لَ ُك ْم َع ُدٌّو ُمبْي ن . ) اﻵنعام- ( The Holy Qur’an Surah Al-An nam:142 says; “ And of the Cattle , are produced some are for burden(workmate, draft) and some are for food(beef, chevon, and mutton), Eat of what Allah has provided for you, and follow not the footsteps of Shaitan (Satan). Surely, he is to you an open enemy “ The Holy Bible Deuteronomy 14:3 says; “ Do not eat anything that the LORD declared unclean, you may eat these animals cattle,sheep,goat, deer, wild sheep, wild goat and antelopes- any animals have devided hooves and also chew the cud (ruminate)” 4 DEDICATION This manual is dedicated to my family ,all halal advocates who continuously strive on research, seek knowledge on halal to serve mankind and the creator Allah Subhana o wa ta ala. “And if all the trees on earth were pens and the sea(were ink where with to write ) with seven seas add to its supply, yet the Words of Allah(knowledge) would not be exhausted….” (Surah Luqman 31 : Verse 27) The Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) said: “The one who would have the worst position in Allah's sight on the Day of Resurrection would be a learned man whom people did not profit from his learning”.(Darimi). -

Hot Pot Taste Test Paul French Vancouver Nocturnes

HOT POT TASTE TEST PAUL FRENCH VANCOUVER NOCTURNES 2018/03- 04 1 MAR/APR 2018 为您打造 A Publication of HOT POT TASTE TEST PAUL FRENCH VANCOUVER NOCTURNES 出版发行: 云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 地址: 云南省昆明市环城西路609号, 云南新闻出版大楼2306室 责任编辑: 欧阳鹏, 张磊 书号: 978-7-900747-63-1 Since 2001 | 2001年创始 thebeijinger.com A Publication of 广告代理: 北京爱见达广告有限公司 地址: 北京市朝阳区关东店北街核桃园30号 孚兴写字楼C座5层, 100020 Advertising Hotline/广告热线: 5941 0368, [email protected] Since 2006 | 2006年创始 Beijing-kids.com Managing Editor Tom Arnstein Editors Kyle Mullin, Tracy Wang Contributors Jeremiah Jenne, Andrew Killeen, Robynne Tindall, Will Griffith, Tautvile Daugelaite, Andrew Little 国际教育 · 家庭生活 · 社区活动 True Run Media Founder & CEO Michael Wester 国际学校如何帮助 有特殊需要的儿童 How MSB and BSB Shunyi Owner & Co-Founder Toni Ma Give Extra Help to Their Students Art Director Susu Luo 为什么我们很少听说 “学习障碍”? Designer Vila Wu Learning Difficulties: The Elephant in Production Manager Joey Guo Chinese Classrooms Content Marketing Manager Robynne Tindall Marketing Director Lareina Yang Events & Brand Manager Mu Yu Marketing Team Helen Liu, Cindy Zhang, Echo Wang 封面故事 HR Manager Tobal Loyola 我们其实都一样 We Are Different, We Are the Same 2016年11月刊 1 HR & Admin Officer Cao Zheng Finance & Admin Manager Judy Zhao Since 2012 | 2012年创始 Jingkids.com Accountants Vicky Cui, Susan Zhou Digital Development Director Alexandre Froger IT Support Specialist Yan Wen Photographer Uni You Sales Director Sheena Hu Account Managers Winter Liu, Wilson Barrie, Olesya Sedysheva, 国际教育·家庭生活·都市资讯 2018.04 Veronica Wu, Sharon Shang, Fangfang Wang Sales Supporting