China-Russia Relations and Regional Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orbital Debris: a Chronology

NASA/TP-1999-208856 January 1999 Orbital Debris: A Chronology David S. F. Portree Houston, Texas Joseph P. Loftus, Jr Lwldon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas David S. F. Portree is a freelance writer working in Houston_ Texas Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ iv Preface ........................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... vii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ ix The Chronology ............................................................................................................. 1 1961 ......................................................................................................................... 4 1962 ......................................................................................................................... 5 963 ......................................................................................................................... 5 964 ......................................................................................................................... 6 965 ......................................................................................................................... 6 966 ........................................................................................................................ -

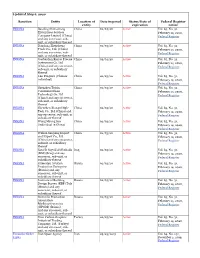

Sanction Entity Location of Date Imposed Status/Date of Federal Register Entity Expiration Notice INKSNA Baoding Shimaotong China 02/03/20 Active Vol

Updated May 6, 2020 Sanction Entity Location of Date imposed Status/Date of Federal Register entity expiration notice INKSNA Baoding Shimaotong China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Enterprises Services February 14, 2020, Company Limited (China) Federal Register and any successor, sub- unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Dandong Zhensheng China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Trade Co., Ltd. (China) February 14, 2020, and any successor, sub- Federal Register unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Gaobeidian Kaituo Precise China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Instrument Co. Ltd February 14, 2020, (China) and any successor, Federal Register sub-unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Luo Dingwen (Chinese China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, individual) February 14, 2020, Federal Register INKSNA Shenzhen Tojoin China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Communications February 14, 2020, Technology Co. Ltd Federal Register (China) and any successor, sub-unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Shenzhen Xiangu High- China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Tech Co., Ltd (China) and February 14, 2020, any successor, sub-unit, or Federal Register subsidiary thereof INKSNA Wong Myong Son China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, (individual in China) February 14, 2020, Federal Register INKSNA Wuhan Sanjiang Import China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, and Export Co., Ltd February 14, 2020, (China) and any successor, Federal Register subunit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada Iraq 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, (KSS) (Iraq) and any February 14, 2020, successor, sub-unit, or Federal Register subsidiary thereof INKSNA Kumertau Aviation Russia 02/03/20 Active Vol. -

1.Russian Information Weapons; 2.Baltic Department of Defense, Or the US Defenses (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) Against Government

Sponsor: USEUCOM Contract No.: W56KGU-17-C-0010 Project No.: 0719S120 The views expressed in this document are those of the author Three Discussions of Russian Concepts: and do not reflect the official policy or position of MITRE, the 1.Russian Information Weapons; 2.Baltic Department of Defense, or the US Defenses (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) against government. Russian Propaganda; and 3.Russia’s Development of Non-Lethal Weapons Author: Timothy Thomas March 2020 Approved for Public Release: Distribution Unlimited. Case Numbers 20-0235; 20-0050; 20-0051; 19-3194; and 20-0145. ©2020 The MITRE Corporation. All rights reserved. McClean, VA 1 FOREWORD Russia has long been captivated by the power of information as a weapon, most notably in a historical sense using propaganda to influence and persuade audiences. With the onset of the information age, the concept’s development and application increased dramatically. The power of information-technologies when applied to weaponry increased the latter’s capabilities due to increased reconnaissance and precision applications. The power of social media was used to influence populations both at home and abroad. Both developments fit perfectly into Russia’s information warfare concept, whose two aspects are information-technical and information-psychological capabilities. Information’s universality, covertness, variety of software and hardware forms and implementation, efficiency of use when choosing a time and place of employment, and, finally, cost effectiveness make it a formidable commodity when assessed as weaponry. Russian efforts to define and use IWes are well documented. In the 1990s there were efforts to define information weapons (IWes) at the United Nations, efforts that failed. -

China Dream, Space Dream: China's Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States

China Dream, Space Dream 中国梦,航天梦China’s Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States A report prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Kevin Pollpeter Eric Anderson Jordan Wilson Fan Yang Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dr. Patrick Besha and Dr. Scott Pace for reviewing a previous draft of this report. They would also like to thank Lynne Bush and Bret Silvis for their master editing skills. Of course, any errors or omissions are the fault of authors. Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. CONTENTS Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 -

The 2019 Joint Agency Commercial Imagery Evaluation—Land Remote

2019 Joint Agency Commercial Imagery Evaluation— Land Remote Sensing Satellite Compendium Joint Agency Commercial Imagery Evaluation NASA • NGA • NOAA • USDA • USGS Circular 1455 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Image of Landsat 8 satellite over North America. Source: AGI’s System Tool Kit. Facing page. In shallow waters surrounding the Tyuleniy Archipelago in the Caspian Sea, chunks of ice were the artists. The 3-meter-deep water makes the dark green vegetation on the sea bottom visible. The lines scratched in that vegetation were caused by ice chunks, pushed upward and downward by wind and currents, scouring the sea floor. 2019 Joint Agency Commercial Imagery Evaluation—Land Remote Sensing Satellite Compendium By Jon B. Christopherson, Shankar N. Ramaseri Chandra, and Joel Q. Quanbeck Circular 1455 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials JACIE as noted in the text. -

Assessing the Impact of US Air Force National Security Space Launch Acquisition Decisions

C O R P O R A T I O N BONNIE L. TRIEZENBERG, COLBY PEYTON STEINER, GRANT JOHNSON, JONATHAN CHAM, EDER SOUSA, MOON KIM, MARY KATE ADGIE Assessing the Impact of U.S. Air Force National Security Space Launch Acquisition Decisions An Independent Analysis of the Global Heavy Lift Launch Market For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR4251 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0399-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Courtesy photo by United Launch Alliance. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The U.S. -

Commercial Space Transportation: 2011 Year in Review

Commercial Space Transportation: 2011 Year in Review COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION: 2011 YEAR IN REVIEW January 2012 HQ-121525.INDD 2011 Year in Review About the Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA/AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 51 United States Code, Subtitle V, Chapter 509 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA/AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA/ AST is directed to encourage, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA/AST’s web site at http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/. Cover: Art by John Sloan (2012) NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. • i • Federal Aviation Administration / Commercial Space Transportation CONTENTS Introduction . .1 Executive Summary . .2 2011 Launch Activity . .3 WORLDWIDE ORBITAL LAUNCH ACTIVITY . 3 Worldwide Launch Revenues . 5 Worldwide Orbital Payload Summary . 5 Commercial Launch Payload Summaries . 6 Non-Commercial Launch Payload Summaries . 7 U .S . AND FAA-LICENSED ORBITAL LAUNCH ACTIVITY . 9 FAA-Licensed Orbital Launch Summary . 9 U .S . and FAA-Licensed Orbital Launch Activity in Detail . -

Assessing Russia's Space Cooperation with China And

ASSESSING RUSSIA’S SPACE COOPERATION WITH CHINA AND INDIA Opportunities and Challenges for Europe Report 12, June 2008 Charlotte MATHIEU, ESPI DISCLAIMER This Report has been prepared for the client in accordance with the associated contract and ESPI will accept no liability for any losses or damages arising out of the provision of the report to third parties. Short Title: ESPI Report 12, June 2008 Editor, Publisher: ESPI European Space Policy Institute A-1030 Vienna, Schwarzenbergplatz 6 Austria http://www.espi.or.at Tel.: +43 1 718 11 18 - 0 Fax - 99 Copyright: © ESPI, June 2008 Rights reserved - No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without permission from ESPI. Citations and extracts to be published by other means are subject to mentioning “source: © ESPI Report 12, June 2008. All rights reserved” and sample transmission to ESPI before publishing. Price: 11,00 EUR Printed by ESA/ESTEC Layout and Design: M. A. Jakob/ESPI and Panthera.cc Ref.: C/20490-003-P13 Report 12, June 2008 2 Russia’s Space Cooperation with China and India Assessing Russia’s Space Cooperation with China and India – Opportunities and Challenges for Europe Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………….... 8 1. Russia in 2008.................................................................................................... 9 1.1. A stronger economy……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 10 1.2. An economy very dependent on the energy sector…………………………………………………… 10 1.3. Political stability…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 1.4. A new posture and the evolution towards a more balanced foreign policy……………… 12 2. Russia and Space……………………………………………………………………………………… 14 2.1. Space as a strategic asset…………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 2.2. -

Updated Version

Updated version HIGHLIGHTS IN SPACE TECHNOLOGY AND APPLICATIONS 2011 A REPORT COMPILED BY THE INTERNATIONAL ASTRONAUTICAL FEDERATION (IAF) IN COOPERATION WITH THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE PEACEFUL USES OF OUTER SPACE, UNITED NATIONS. 28 March 2012 Highlights in Space 2011 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 I. OVERVIEW 5 II. SPACE TRANSPORTATION 10 A. CURRENT LAUNCH ACTIVITIES 10 B. DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES 14 C. LAUNCH FAILURES AND INVESTIGATIONS 26 III. ROBOTIC EARTH ORBITAL ACTIVITIES 29 A. REMOTE SENSING 29 B. GLOBAL NAVIGATION SYSTEMS 33 C. NANOSATELLITES 35 D. SPACE DEBRIS 36 IV. HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT 38 A. INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION DEPLOYMENT AND OPERATIONS 38 2011 INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION OPERATIONS IN DETAIL 38 B. OTHER FLIGHT OPERATIONS 46 C. MEDICAL ISSUES 47 D. SPACE TOURISM 48 V. SPACE STUDIES AND EXPLORATION 50 A. ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS 50 B. PLASMA AND ATMOSPHERIC PHYSICS 56 C. SPACE EXPLORATION 57 D. SPACE OPERATIONS 60 VI. TECHNOLOGY - IMPLEMENTATION AND ADVANCES 65 A. PROPULSION 65 B. POWER 66 C. DESIGN, TECHNOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT 67 D. MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES 69 E. INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND DATASETS 69 F. AUTOMATION AND ROBOTICS 72 G. SPACE RESEARCH FACILITIES AND GROUND STATIONS 72 H. SPACE ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS & MEDICAL ADVANCES 74 VII. SPACE AND SOCIETY 75 A. EDUCATION 75 B. PUBLIC AWARENESS 79 C. CULTURAL ASPECTS 82 Page 3 Highlights in Space 2011 VIII. GLOBAL SPACE DEVELOPMENTS 83 A. GOVERNMENT PROGRAMMES 83 B. COMMERCIAL ENTERPRISES 84 IX. INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 92 A. GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTS AND ORGANISATIONS 92 B. EUROPE 94 C. AFRICA 101 D. ASIA 105 E. THE AMERICAS 110 F. -

HOW CHINA HAS INTEGRATED ITS SPACE PROGRAM INTO ITS BROADER FOREIGN POLICY Dean Cheng

HOW CHINA HAS INTEGRATED ITS SPACE PROGRAM INTO ITS BROADER FOREIGN POLICY Dean Cheng INTRODUCTION: CHINA AS A SPACE POWER Because of the way the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is governed, it is able to pursue a more holistic approach to policy. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) not only controls the government, but has a presence in every major organization, including economic, technical, and academic entities. Consequently, China is able to pursue not only a “whole of government” approach to policy, but a “whole of society” approach, incorporating elements that are often beyond the reach of other nations. This has meant that China has been able to use its space program to promote various aspects of its foreign policy, integrating it not only into traditional diplomatic and security efforts, but also trade and even industrial elements. Indeed, the incorporation of space elements into Chinese foreign policy thinking has been characteristic of China’s aerospace efforts from its earliest days. Where both Washington and Moscow’s space efforts were initially motivated in part by the desire to undertake surveillance missions, prestige played a much greater role in motivating the early phases of China’s space program. The senior Chinese leadership saw the development of space capabilities as reflecting on China’s place in the international order. Thus, in the wake of Sputnik, Chairman Mao Zedong advocated the creation of a Chinese space program. As he stated in May 1958, at the Second Plenum of the Eighth Party Congress, “we should also manufacture satellites.”1 The Chinese leadership, even in 1958, saw the ability to compete in aerospace as reflecting their broader place in the international environment. -

A SPACE EXPLORATION INDUSTRY AGENDA for INDIA Chaitanya Giri

A SPACE EXPLORATION INDUSTRY AGENDA FOR INDIA Chaitanya Giri, Fellow, Space & Oceans Studies Programme Paper No. 23 | May 2020 Executive Executive Director: Manjeet Kripalani Director: Neelam Deo Publication Editor: Christopher Conte & Manjeet Kripalani Copy Editor: Nandini Bhaskaran Website and Publications Associate: Sukhmani Sharma Designer: Debarpan Das Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations @GatewayHouseIND @GatewayHouse.in For more information on how to participate in Gateway House’s outreach initiatives, please email [email protected] © Copyright 2020, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in India by Airolite Printers TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...............................................................................................................................................08 1. An Opportune Moment for Global Industry 4.0 in Space.................................................................10 2. New Spacefaring Nations Focus on Integrating Industry 4.0 and Space Exploration....................12 2.1 United Arab Emirates – Building a Martian City with 3D-Printing Technology..........................14 2.2 Luxembourg – Enabling Asteroid Mining with Blockchain Technology.....................................15 -

Historical (1750–2014) Anthropogenic Emissions of Reactive Gases and Aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS)

Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 369–408, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-369-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) Rachel M. Hoesly1, Steven J. Smith1,2, Leyang Feng1, Zbigniew Klimont3, Greet Janssens-Maenhout4, Tyler Pitkanen1, Jonathan J. Seibert1, Linh Vu1, Robert J. Andres5, Ryan M. Bolt1, Tami C. Bond6, Laura Dawidowski7, Nazar Kholod1, June-ichi Kurokawa8, Meng Li9, Liang Liu6, Zifeng Lu10, Maria Cecilia P. Moura1, Patrick R. O’Rourke1, and Qiang Zhang9 1Joint Global Change Research Institute, Pacific Northwest National Lab, College Park, MD, USA 2Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA 3International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria 4European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Directorate Energy, Transport & Climate, Via Fermi 2749, 21027 Ispra, Italy 5Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, USA 6Dept. of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA 7Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica, Buenos Aires, Argentina 8Japan Environmental Sanitation Center, Asia Center for Air Pollution Research, Atmospheric Research Department, Niigata, Niigata, Japan 9Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 10Energy Systems Division, Argonne National Laboratory,