The Effect of Neptune's Accretion on Pluto and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

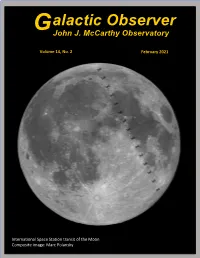

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Distant Ekos: 2012 BX85 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG

Issue No. 79 February 2012 r ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 8 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Newsletter Information .............................. .....9 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There was 1 new TNO discovery announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2012 BX85 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG Objects recently assigned numbers: 2010 EP65 = (312645) 2008 QD4 = (315898) 2010 EN65 = (316179) 2008 AP129 = (315530) Objects recently assigned names: 1997 CS29 = Sila-Nunam Current number of TNOs: 1249 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 337 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 8 Out of a total of 1594 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 624 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 316 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS The Dynamical Evolution of Dwarf Planet (136108) Haumea’s Collisional Family: General Properties and Implications for the Trans-Neptunian Belt Patryk Sofia Lykawka1, Jonathan Horner2, Tadashi Mukai3 and Akiko M. Nakamura3 1 Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Japan 2 Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Australia 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kobe University, Japan Recently, the first collisional family was identified in the trans-Neptunian belt (otherwise known as the Edgeworth-Kuiper belt), providing direct evidence of the importance of collisions between trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). -

1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects - a Review Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract Our understanding of the history of the solar system has undergone a revolution in recent years, owing to new theoretical insights into the origin of Pluto and the discovery of the Kuiper belt and its rich dynamical structure. The emerging picture of dramatic orbital migration of the planets driven by interaction with the primordial Kuiper belt is thought to have produced the final solar system architecture that we live in today. This paper gives a brief summary of this new view of our solar system's history, and reviews the astronomical evidence in the resonant populations of the Kuiper belt. Introduction Lying at the edge of the visible solar system, observational confirmation of the existence of the Kuiper belt came approximately a quarter-century ago with the discovery of the distant minor planet (15760) Albion (formerly 1992 QB1, Jewitt & Luu 1993). With the clarity of hindsight, we now recognize that Pluto was the first discovered member of the Kuiper belt. The current census of the Kuiper belt includes more than 2000 minor planets at heliocentric distances between ~30 au and ~50 au. Their orbital distribution reveals a rich dynamical structure shaped by the gravitational perturbations of the giant planets, particularly Neptune. Theoretical analysis of these structures has revealed a remarkable dynamic history of the solar system. The story is as follows (see Fernandez & Ip 1984, Malhotra 1993, Malhotra 1995, Fernandez & Ip 1996, and many subsequent works). -

1950 Da, 205, 269 1979 Va, 230 1991 Ry16, 183 1992 Kd, 61 1992

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. Burbine Index More Information 356 Index 1950 DA, 205, 269 single scattering, 142, 143, 144, 145 1979 VA, 230 visual Bond, 7 1991 RY16, 183 visual geometric, 7, 27, 28, 163, 185, 189, 190, 1992 KD, 61 191, 192, 192, 253 1992 QB1, 233, 234 Alexandra, 59 1993 FW, 234 altitude, 49 1994 JR1, 239, 275 Alvarez, Luis, 258 1999 JU3, 61 Alvarez, Walter, 258 1999 RL95, 183 amino acid, 81 1999 RQ36, 61 ammonia, 223, 301 2000 DP107, 274, 304 amoeboid olivine aggregate, 83 2000 GD65, 205 Amor, 251 2001 QR322, 232 Amor group, 251 2003 EH1, 107 Anacostia, 179 2007 PA8, 207 Anand, Viswanathan, 62 2008 TC3, 264, 265 Angelina, 175 2010 JL88, 205 angrite, 87, 101, 110, 126, 168 2010 TK7, 231 Annefrank, 274, 275, 289 2011 QF99, 232 Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET), 71 2012 DA14, 108 Antarctica, 69–71 2012 VP113, 233, 244 aphelion, 30, 251 2013 TX68, 64 APL, 275, 292 2014 AA, 264, 265 Apohele group, 251 2014 RC, 205 Apollo, 179, 180, 251 Apollo group, 230, 251 absorption band, 135–6, 137–40, 145–50, Apollo mission, 129, 262, 299 163, 184 Apophis, 20, 269, 270 acapulcoite/ lodranite, 87, 90, 103, 110, 168, 285 Aquitania, 179 Achilles, 232 Arecibo Observatory, 206 achondrite, 84, 86, 116, 187 Aristarchus, 29 primitive, 84, 86, 103–4, 287 Asporina, 177 Adamcarolla, 62 asteroid chronology function, 262 Adeona family, 198 Asteroid Zoo, 54 Aeternitas, 177 Astraea, 53 Agnia family, 170, 198 Astronautica, 61 AKARI satellite, 192 Aten, 251 alabandite, 76, 101 Aten group, 251 Alauda family, 198 Atira, 251 albedo, 7, 21, 27, 185–6 Atira group, 251 Bond, 7, 8, 9, 28, 189 atmosphere, 1, 3, 8, 43, 66, 68, 265 geometric, 7 A- type, 163, 165, 167, 169, 170, 177–8, 192 356 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. -

Atmospheres and Surfaces of Small Bodies and Dwarf Planets in the Kuiper Belt

EPJ Web of Conferences 9, 267–276 (2010) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201009021 c Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2010 Atmospheres and surfaces of small bodies and dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt E.L. Schallera Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Abstract. Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) are icy relics orbiting the sun beyond Neptune left over from the planetary accretion disk. These bodies act as unique tracers of the chemical, thermal, and dynamical history of our solar system. Over 1000 Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) and centaurs (objects with perihelia between the giant planets) have been discovered over the past two decades. While the vast majority of these objects are small (< 500 km in diameter), there are now many objects known that are massive enough to attain hydrostatic equilibrium (and are therefore considered dwarf planets) including Pluto, Eris, MakeMake, and Haumea. The discoveries of these large objects, along with the advent of large (> 6-meter) telescopes, have allowed for the first detailed studies of their surfaces and atmospheres. Visible and near-infrared spectroscopy of KBOs and centaurs has revealed a great diversity of surface compositions. Only the largest and coldest objects are capable of retaining volatile ices and atmospheres. Knowledge of the dynamics, physical properties, and collisional history of objects in the Kuiper belt is important for understanding solar system formation and evolution. 1 Introduction The existence of a belt of debris beyond Neptune left over from planetary accretion was proposed by Kuiper in 1951 [1]. Though Pluto was discovered in 1930, it took over sixty years for other Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) to be detected [2] and for Pluto to be recognized as the first known member of a larger population now known to consist of over 1000 objects (Fig. -

Colours of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System II - a Statistical Analysis, Revisited

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. MBOSS2 c ESO 2012 April 26, 2012 Colours of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System II - A Statistical Analysis, Revisited O. R. Hainaut1, H. Boehnhardt2, and S. Protopapa3 1 European Southern Observatory (ESO), Karl Schwarzschild Straße, 85 748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Sonnensystemforschung, Max-Planck Straße 2, 37 191 Katlenburg- Lindau, Germany 3 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20 742-2421, USA Received —; accepted — ABSTRACT We present an update of the visible and near-infrared colour database of Minor Bodies in the outer Solar System (MBOSSes), now including over 2000 measurement epochs of 555 objects, extracted from 100 articles. The list is fairly complete as of December 2011. The database is now large enough that dataset with a high dispersion can be safely identified and rejected from the analysis. The method used is safe for individual outliers. Most of the rejected papers were from the early days of MBOSS photometry. The individual measurements were combined so not to include possible rotational artefacts. The spectral gradient over the visible range is derived from the colours, as well as the R absolute magnitude M(1, 1). The average colours, absolute magnitude, spectral gradient are listed for each object, as well as their physico-dynamical classes using a classification adapted from Gladman et al., 2008. Colour-colour diagrams, histograms and various other plots are presented to illustrate and in- vestigate class characteristics and trends with other parameters, whose significance are evaluated using standard statistical tests. -

The Kuiper Belt and the Primordial Evolution of the Solar System

Morbidelli and Brown: Kuiper Belt and Evolution of Solar System 175 The Kuiper Belt and the Primordial Evolution of the Solar System A. Morbidelli Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur M. E. Brown California Institute of Technology We discuss the structure of the Kuiper belt as it can be inferred from the first decade of observations. In particular, we focus on its most intriguing properties — the mass deficit, the inclination distribution, and the apparent existence of an outer edge and a correlation among inclinations, colors, and sizes — which clearly show that the belt has lost the pristine structure of a dynamically cold protoplanetary disk. Understanding how the Kuiper belt acquired its present structure will provide insight into the formation of the outer planetary system and its early evolution. We critically review the scenarios that have been proposed so far for the pri- mordial sculpting of the belt. None of them can explain in a single model all the observed properties; the real history of the Kuiper belt probably requires a combination of some of the proposed mechanisms. 1. INTRODUCTION A primary goal of this chapter is to present the orbital structure of the Kuiper belt as it stands based on the current When Edgeworth and Kuiper conjectured the existence observations. We start in section 2 by presenting the various of a belt of small bodies beyond Neptune — now known subclasses that constitute the transneptunian population. as the Kuiper belt — they certainly were imagining a disk Then in section 3 we describe some striking properties of of planetesimals that preserved the pristine conditions of the the population, such as its mass deficit, inclination excita- protoplanetary disk. -

Destination Dwarf Planets: a Panel Discussion

Destination Dwarf Planets: A Panel Discussion OPAG, August 2019 Convened: Orkan Umurhan (SETI/NASA-ARC) Co-Panelists: Walt Harris (LPL, UA) Kathleen Mandt (JHUAPL) Alan Stern (SWRI) Dwarf Planets/KBO: a rogues gallery Triton Unifying Story for these bodies awaits Perihelio n/ Diamet Aphelion DocumentGoals 09.2018) from OPAG (Taken Name Surface characteristics Other observations/ hypotheses Moons er (km) /Current Distance (AU) Eris ~2326 P=38 Appears almost white, albedo of 0.96, higher Largest KBO by mass second Dysnomia A=98 than any other large Solar System body except by size. Models of internal C=96 Enceledus. Methane ice appears to be quite radioactive decay indicate evenly spread over the surface that a subsurface water ocean may be stable Haumea ~1600 P=35 Displays a white surface with an albedo of 0.6- Is a triaxial ellipsoid, with its Hi’iaka and A=51 0.8 , and a large, dark red area . Surface shows major axis twice as long as Namaka C=51 the presence of crystalline water ice (66%-80%) , the minor. Rapid rotation (~4 but no methane, and may have undergone hrs), high density, and high resurfacing in the last 10 Myr. Hydrogen cyanide, albedo may be the result of a phyllosilicate clays, and inorganic cyanide salts giant collision. Has the only may be present , but organics are no more than ring system known for a TNO. 8% 2007 OR10 ~1535 P=33 Amongst the reddest objects known, perhaps due May retain a thin methane S/(225088) A=101 to the abundant presence of methane frosts atmosphere 1 C=87 (tholins?) across the surface.Surface also show the presence of water ice. -

The Color Distribution of the Plutinos: Size and Inclination Dependent

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 13, EPSC-DPS2019-1260-2, 2019 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. The color distribution of the Plutinos: size and inclination dependent Mike Alexandersen (1), Rosemary Pike (1), Yeeun Hyun (1, 2), and Ashwani Rajan (1, 3) (1) Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Taiwan ([email protected]), (2) Kyung Hee University, Korea, (3) Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, India Abstract The color distribution of medium and small trans- Neptunian objects (TNOs) in the outer Solar System is complex, with three major surface types [3], rang- ing in color from 0.4 g r 1.1. The Kuiper ≤ − ≤ belt includes a component of low-inclination and low- eccentricity objects between 40 48 AU referred to as ∼ the cold classicals, which are thought to be primordial and have formed roughly in place. These cold clas- sicals have almost exclusively red in g r and have − unique r z colors [3]. Are other TNO populations Figure 2: Inclination versus g r color for our 15 − − are dynamically excited and thought to have formed Plutino sample. The dotted line corresponds to the elsewhere and been scattered by planetary migration. typical division between dynamically ‘hot’ and ‘cold’. The color distribution above and below the dotted line are different at 95% confidence. the larger Plutinos (5.5 < Hr <8.4) at 95% confidence (see distributions in Figure 1). This suggests that the small objects have a different formation mechanism than the large objects, possibly being primarily col- lisional fragments. This transition magnitude corre- sponds to the transition point in the magnitude distri- bution seen for many populations ([1] for plutinos). -

Jjmonl 1612.Pmd

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 9, No. 12 December 2016 Water - the elusive elixir of life in the cosmos - Is it even closer than we thought? The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 www.mccarthyobservatory.org Allan Ostergren Website Development JJMO Staff Marc Polansky It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory Technical Support has established itself as a significant educational and Bob Lambert recreational resource within the western Connecticut Dr. Parker Moreland community. Steve Allison Tom Heydenburg Steve Barone Jim Johnstone Colin Campbell Carly KleinStern Dennis Cartolano Bob Lambert Route Mike Chiarella Roger Moore Jeff Chodak Parker Moreland, PhD Bill Cloutier Allan Ostergren Doug Delisle Marc Polansky Cecilia Detrich Joe Privitera Dirk Feather Monty Robson Randy Fender Don Ross Randy Finden Gene Schilling John Gebauer Katie Shusdock Elaine Green Paul Woodell Tina Hartzell Amy Ziffer In This Issue "OUT THE WINDOW ON YOUR LEFT"............................... 3 COMMONLY USED TERMS .............................................. 17 TAURUS-LITTROW .......................................................... 3 EARTH-SUN LAGRANGE POINTS & JAMES WEBB TELESCOPE 17 OVER THE TOP ............................................................... 4 REFERENCES ON DISTANCES ........................................