1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

1 Trajectory Design for the Transiting Exoplanet

TRAJECTORY DESIGN FOR THE TRANSITING EXOPLANET SURVEY SATELLITE Donald J. Dichmann(1), Joel J.K. Parker(2), Trevor W. Williams(3), Chad R. Mendelsohn(4) (1,2,3,4)Code 595.0, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Greenbelt MD 20771. 301-286-6621. [email protected] Abstract: The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) mission, scheduled to be launched in 2017. TESS will travel in a highly eccentric orbit around Earth, with initial perigee radius near 17 Earth radii (Re) and apogee radius near 59 Re. The orbit period is near 2:1 resonance with the Moon, with apogee nearly 90 degrees out-of-phase with the Moon, in a configuration that has been shown to be operationally stable. TESS will execute phasing loops followed by a lunar flyby, with a final maneuver to achieve 2:1 resonance with the Moon. The goals of a resonant orbit with long-term stability, short eclipses and limited oscillations of perigee present significant challenges to the trajectory design. To rapidly assess launch opportunities, we adapted the Schematics Window Methodology (SWM76) launch window analysis tool to assess the TESS mission constraints. To understand the long-term dynamics of such a resonant orbit in the Earth-Moon system we employed Dynamical Systems Theory in the Circular Restricted 3-Body Problem (CR3BP). For precise trajectory analysis we use a high-fidelity model and multiple shooting in the General Mission Analysis Tool (GMAT) to optimize the maneuver delta-V and meet mission constraints. Finally we describe how the techniques we have developed can be applied to missions with similar requirements. -

Secular Chaos and Its Application to Mercury, Hot Jupiters, and The

Secular chaos and its application to Mercury, hot SPECIAL FEATURE Jupiters, and the organization of planetary systems Yoram Lithwicka,b,1 and Yanqin Wuc aDepartment of Physics and Astronomy and bCenter for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208; and cDepartment of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada M5S 3H4 Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board October 31, 2013 (received for review May 2, 2013) In the inner solar system, the planets’ orbits evolve chaotically, by including the most important MMRs (11).] It is the cause, for driven primarily by secular chaos. Mercury has a particularly cha- example, of Earth’s eccentricity-driven Milankovitch cycle. How- otic orbit and is in danger of being lost within a few billion years. ever, on timescales ≳107 years, the evolution is chaotic (e.g., Fig. Just as secular chaos is reorganizing the solar system today, so it 1), in sharp contrast to the prediction of linear secular theory. has likely helped organize it in the past. We suggest that extra- That appears to be puzzling, given the small eccentricities and solar planetary systems are also organized to a large extent by inclinations in the solar system. secular chaos. A hot Jupiter could be the end state of a secularly However, despite its importance, there has been little theo- chaotic planetary system reminiscent of the solar system. How- retical understanding of how secular chaos works. Conversely, ever, in the case of the hot Jupiter, the innermost planet was chaos driven by MMRs is much better understood. -

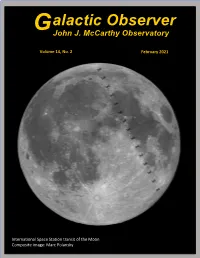

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds

Jonathan Powell Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds The Patrick Moore The Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/3192 Rare Astronomical Sights and Sounds Jonathan Powell Jonathan Powell Ebbw Vale, United Kingdom ISSN 1431-9756 ISSN 2197-6562 (electronic) The Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series ISBN 978-3-319-97700-3 ISBN 978-3-319-97701-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97701-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953700 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Unseen 'Planetary Mass Object' Signalled by Warped Kuiper Belt 22 June 2017, by Daniel Stolte

Unseen 'planetary mass object' signalled by warped Kuiper Belt 22 June 2017, by Daniel Stolte orbital tilts (inclinations) that average out to what planetary scientists call the invariable plane of the solar system, the most distant of the Kuiper Belt's objects do not. Their average plane, Volk and Malhotra discovered, is tilted away from the invariable plane by about eight degrees. In other words, something unknown is warping the average orbital plane of the outer solar system. "The most likely explanation for our results is that there is some unseen mass," says Volk, a postdoctoral fellow at LPL and the lead author of the study. "According to our calculations, something A yet to be discovered, unseen "planetary mass object" as massive as Mars would be needed to cause the makes its existence known by ruffling the orbital plane of warp that we measured." distant Kuiper Belt objects, according to research by Kat Volk and Renu Malhotra of the UA's Lunar and Planetary The Kuiper Belt lies beyond the orbit of Neptune Laboratory. The object is pictured on a wide orbit far and extends to a few hundred Astronomical Units, beyond Pluto in this artist's illustration. Credit: Heather or AU, with one AU representing the distance Roper/LPL between Earth and the sun. Like its inner solar system cousin, the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the Kuiper Belt hosts a vast number of minor planets, mostly small icy bodies (the An unknown, unseen "planetary mass object" may precursors of comets), and a few dwarf planets. lurk in the outer reaches of our solar system, according to new research on the orbits of minor For the study, Volk and Malhotra analyzed the tilt planets to be published in the Astronomical angles of the orbital planes of more than 600 Journal. -

Distant Ekos: 2012 BX85 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG

Issue No. 79 February 2012 r ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 8 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Newsletter Information .............................. .....9 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There was 1 new TNO discovery announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2012 BX85 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG Objects recently assigned numbers: 2010 EP65 = (312645) 2008 QD4 = (315898) 2010 EN65 = (316179) 2008 AP129 = (315530) Objects recently assigned names: 1997 CS29 = Sila-Nunam Current number of TNOs: 1249 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 337 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 8 Out of a total of 1594 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 624 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 316 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS The Dynamical Evolution of Dwarf Planet (136108) Haumea’s Collisional Family: General Properties and Implications for the Trans-Neptunian Belt Patryk Sofia Lykawka1, Jonathan Horner2, Tadashi Mukai3 and Akiko M. Nakamura3 1 Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Japan 2 Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Australia 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kobe University, Japan Recently, the first collisional family was identified in the trans-Neptunian belt (otherwise known as the Edgeworth-Kuiper belt), providing direct evidence of the importance of collisions between trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). -

Guide to the Extended Versions of MPC Data Files Based on the MPCORB Format

Guide to the Extended Versions of MPC Data Files Based on the MPCORB Format Last updated: 2016/04/19 by J.L. Galache Introduction The Minor Planet Center (MPC) has been providing the orbits of minor planets in the form of a file, MPCORB.DAT, since the mid '90s (1990s, not 1890s). Back then there were only a few thousand known asteroids, compared to the several hundred thousand of today, so a flat text file was the appropriate way to circulate these data. It was also a time when most orbit computations were programmed in Fortran, which ingested data no other way. MPCORB.DAT has therefore always been, and continues to be, a fixed-width file (see Table 1 for the current format description1). In fact, all original data files available on the MPC website are flat text files (even the orbits files provided for planetarium-type/sky simulation software packages are simply text files of varying format2). In the early years of the 2010s, possibly due to the rising popularity of the scripting language Python amongst astronomers, and an increased interest from developers wanting to write asteroid-themed tools, requests were received to provide data in other, easier to parse formats, e.g., JSON, CSV, SQL, etc. At the same time, astronomers and developers alike wanted more information than was currently been provided in MPCORB.DAT; information that did exist on the MPC website in other, often hard to find, files. Here was an opportunity to add some new data to existing files, while also making them available in other formats. -

Estabilidade De Veículos Espaciais Em Ressonância

sid.inpe.br/mtc-m21c/2018/03.12.13.05-TDI ESTABILIDADE DE VEÍCULOS ESPACIAIS EM RESSONÂNCIA Rubens Antonio Condeles Júnior Tese de Doutorado do Curso de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia e Tecnologia Espaciais/Mecânica Espacial e Controle, orientada pelos Drs. Antonio Fernando Bertachini de Almeida Prado, e Tadashi Yokoyama, aprovada em 06 de abril de 2018. URL do documento original: <http://urlib.net/8JMKD3MGP3W34R/3QMPS3E> INPE São José dos Campos 2018 PUBLICADO POR: Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais - INPE Gabinete do Diretor (GBDIR) Serviço de Informação e Documentação (SESID) Caixa Postal 515 - CEP 12.245-970 São José dos Campos - SP - Brasil Tel.:(012) 3208-6923/6921 E-mail: [email protected] COMISSÃO DO CONSELHO DE EDITORAÇÃO E PRESERVAÇÃO DA PRODUÇÃO INTELECTUAL DO INPE (DE/DIR-544): Presidente: Maria do Carmo de Andrade Nono - Conselho de Pós-Graduação (CPG) Membros: Dr. Plínio Carlos Alvalá - Centro de Ciência do Sistema Terrestre (COCST) Dr. André de Castro Milone - Coordenação-Geral de Ciências Espaciais e Atmosféricas (CGCEA) Dra. Carina de Barros Melo - Coordenação de Laboratórios Associados (COCTE) Dr. Evandro Marconi Rocco - Coordenação-Geral de Engenharia e Tecnologia Espacial (CGETE) Dr. Hermann Johann Heinrich Kux - Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra (CGOBT) Dr. Marley Cavalcante de Lima Moscati - Centro de Previsão de Tempo e Estudos Climáticos (CGCPT) Silvia Castro Marcelino - Serviço de Informação e Documentação (SESID) BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL: Dr. Gerald Jean Francis Banon Clayton Martins Pereira - Serviço de Informação -

The Minor Planets

The Minor Planets Swinburne Astronomy Online 3D PDF c SAO 2012 The Minor Planets c Swinburne Astronomy Online 2012 1 Description 1.1 Minor planets Our view of the Solar System has changed dramatically over the past 15 years with the discovery of new classes of small bodies. Mi- nor planets are another name for asteroids, or celestial bodies that orbit the Sun that are not otherwise classed as planets or comets. Generally, minor planets are relatively small rocky bodies, while comets are icy bodies that become active when their orbits carry them close to the Sun. (An \active" comet exhibits a large coma and a long tail.) The minor planets can be classified by their orbital characteristics. In this 3D PDF, we have included 5 classes of minor planets: (1) the Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs), (2) the main belt asteroids, (3) the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter, (4) the Centaurs, and (5) the Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). The dataset used comes from the Minor Planets Centre. As of 19 November 2012, there were 9,346 NEAs (comprising 732 Atens, 4686 Apollos and 3928 Amors); 581,613 main belt asteroids; 5,407 jovian Trojans; 330 Centaurs; and 1,150 TNOs. (Note than in this 3D PDF, we have only included 11,678 main belt asteroids.) • The Near Earth Asteroids have perihelion distances of less than 1.3 AU, and include the following sub-classes: { Atens have aphelion distances greater than 0.983 AU, and semi-major axes less than 1 AU { Apollos have perihelion distances less than 1.017 AU, and semi-major axes greater than 1 AU { Amors have perihelion distances between 1.017 and 1.3 AU and semi-major axes greater than 1 AU • The main belt asteroids reside between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, with most of the asteroids orbiting between about 2.1 AU and 3.3 AU. -

Orbital Resonances and Chaos in the Solar System

Solar system Formation and Evolution ASP Conference Series, Vol. 149, 1998 D. Lazzaro et al., eds. ORBITAL RESONANCES AND CHAOS IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Blvd, Houston, TX 77058, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Long term solar system dynamics is a tale of orbital resonance phe- nomena. Orbital resonances can be the source of both instability and long term stability. This lecture provides an overview, with simple models that elucidate our understanding of orbital resonance phenomena. 1. INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of resonance is a familiar one to everybody from childhood. A very young child is delighted in a playground swing when an older companion drives the swing at its natural frequency and rapidly increases the swing amplitude; the older child accomplishes the same on her own without outside assistance by driving the swing at a frequency twice that of its natural frequency. Resonance phenomena in the Solar system are essentially similar – the driving of a dynamical system by a periodic force at a frequency which is a rational multiple of the natural frequency. In fact, there are many mathematical similarities with the playground analogy, including the fact of nonlinearity of the oscillations, which plays a fundamental role in the long term evolution of orbits in the planetary system. But there is also an important difference: in the playground, the child adjusts her driving frequency to remain in tune – hence in resonance – with the natural frequency which changes with the amplitude of the swing. Such self-tuning is sometimes realized in the Solar system; but it is more often and more generally the case that resonances come-and-go.