The Kuiper Belt Hu- Now Known As the Kuiper Belt Have Been Discoveredin the As Lying Beyond the Orbit of Neptune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

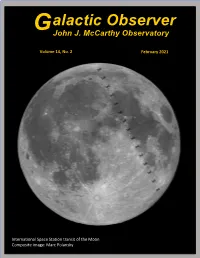

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Mass of the Kuiper Belt · 9Th Planet PACS 95.10.Ce · 96.12.De · 96.12.Fe · 96.20.-N · 96.30.-T

Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Mass of the Kuiper Belt E. V. Pitjeva · N. P. Pitjev Received: 13 December 2017 / Accepted: 24 August 2018 The final publication ia available at Springer via http://doi.org/10.1007/s10569-018-9853-5 Abstract The Kuiper belt includes tens of thousands of large bodies and millions of smaller objects. The main part of the belt objects is located in the annular zone between 39.4 au and 47.8 au from the Sun, the boundaries correspond to the average distances for orbital resonances 3:2 and 2:1 with the motion of Neptune. One-dimensional, two-dimensional, and discrete rings to model the total gravitational attraction of numerous belt objects are consid- ered. The discrete rotating model most correctly reflects the real interaction of bodies in the Solar system. The masses of the model rings were determined within EPM2017—the new version of ephemerides of planets and the Moon at IAA RAS—by fitting spacecraft ranging observations. The total mass of the Kuiper belt was calculated as the sum of the masses of the 31 largest trans-neptunian objects directly included in the simultaneous integration and the estimated mass of the model of the discrete ring of TNO. The total mass −2 is (1.97 ± 0.30) · 10 m⊕. The gravitational influence of the Kuiper belt on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune exceeds at times the attraction of the hypothetical 9th planet with a mass of ∼ 10 m⊕ at the distances assumed for it. -

Distant Ekos: 2012 BX85 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG

Issue No. 79 February 2012 r ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 8 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Newsletter Information .............................. .....9 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There was 1 new TNO discovery announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2012 BX85 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG Objects recently assigned numbers: 2010 EP65 = (312645) 2008 QD4 = (315898) 2010 EN65 = (316179) 2008 AP129 = (315530) Objects recently assigned names: 1997 CS29 = Sila-Nunam Current number of TNOs: 1249 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 337 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 8 Out of a total of 1594 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 624 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 316 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS The Dynamical Evolution of Dwarf Planet (136108) Haumea’s Collisional Family: General Properties and Implications for the Trans-Neptunian Belt Patryk Sofia Lykawka1, Jonathan Horner2, Tadashi Mukai3 and Akiko M. Nakamura3 1 Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Japan 2 Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Australia 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kobe University, Japan Recently, the first collisional family was identified in the trans-Neptunian belt (otherwise known as the Edgeworth-Kuiper belt), providing direct evidence of the importance of collisions between trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). -

1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects - a Review Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract Our understanding of the history of the solar system has undergone a revolution in recent years, owing to new theoretical insights into the origin of Pluto and the discovery of the Kuiper belt and its rich dynamical structure. The emerging picture of dramatic orbital migration of the planets driven by interaction with the primordial Kuiper belt is thought to have produced the final solar system architecture that we live in today. This paper gives a brief summary of this new view of our solar system's history, and reviews the astronomical evidence in the resonant populations of the Kuiper belt. Introduction Lying at the edge of the visible solar system, observational confirmation of the existence of the Kuiper belt came approximately a quarter-century ago with the discovery of the distant minor planet (15760) Albion (formerly 1992 QB1, Jewitt & Luu 1993). With the clarity of hindsight, we now recognize that Pluto was the first discovered member of the Kuiper belt. The current census of the Kuiper belt includes more than 2000 minor planets at heliocentric distances between ~30 au and ~50 au. Their orbital distribution reveals a rich dynamical structure shaped by the gravitational perturbations of the giant planets, particularly Neptune. Theoretical analysis of these structures has revealed a remarkable dynamic history of the solar system. The story is as follows (see Fernandez & Ip 1984, Malhotra 1993, Malhotra 1995, Fernandez & Ip 1996, and many subsequent works). -

Distant Ekos

Issue No. 51 March 2007 s DISTANT EKO di The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter r Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 6 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Titles of 2 Submitted Papers ........................... 6 Title of 1 Other Paper of Interest ....................... 7 Title of 1 Conference Contribution ..................... 7 Abstracts of 3 Book Chapters ........................... 8 Newsletter Information .............................. 10 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS More binaries...lots more... In IAUC 8811, 8814, 8815, and 8816, Noll et al. report satellites of five TNOs from HST observations: • (123509) 2000 WK183, separation = 0.080 arcsec, magnitude difference = 0.4 mag • 2002 WC19, separation = 0.090 arcsec, magnitude difference = 2.5 mag • 2002 GZ31, separation = 0.070 arcsec, magnitude difference = 1.0 mag • 2004 PB108, separation = 0.172 arcsec, magnitude difference = 1.2 mag • (60621) 2000 FE8, separation = 0.044 arcsec, magnitude difference = 0.6 mag In IAUC 8812, Brown and Suer report satellites of four TNOs from HST observations: • (50000) Quaoar, separation = 0.35 arcsec, magnitude difference = 5.6 mag • (55637) 2002 UX25, separation = 0.164 arcsec, magnitude difference = 2.5 mag • (90482) Orcus, separation = 0.25 arcsec, magnitude difference = 2.7 mag • 2003 AZ84, separation = 0.22 arcsec, magnitude difference = 5.0 mag ................................................... ................................................ -

Solar System Planet and Dwarf Planet Fact Sheet

Solar System Planet and Dwarf Planet Fact Sheet The planets and dwarf planets are listed in their order from the Sun. Mercury The smallest planet in the Solar System. The closest planet to the Sun. Revolves the fastest around the Sun. It is 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit hotter on its daytime side than on its night time side. Venus The hottest planet. Average temperature: 864 F. Hotter than your oven at home. It is covered in clouds of sulfuric acid. It rains sulfuric acid on Venus which comes down as virga and does not reach the surface of the planet. Its atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide (CO2). It has thousands of volcanoes. Most are dormant. But some might be active. Scientists are not sure. It rotates around its axis slower than it revolves around the Sun. That means that its day is longer than its year! This rotation is the slowest in the Solar System. Earth Lots of water! Mountains! Active volcanoes! Hurricanes! Earthquakes! Life! Us! Mars It is sometimes called the "red planet" because it is covered in iron oxide -- a substance that is the same as rust on our planet. It has the highest volcano -- Olympus Mons -- in the Solar System. It is not an active volcano. It has a canyon -- Valles Marineris -- that is as wide as the United States. It once had rivers, lakes and oceans of water. Scientists are trying to find out what happened to all this water and if there ever was (or still is!) life on Mars. It sometimes has dust storms that cover the entire planet. -

1950 Da, 205, 269 1979 Va, 230 1991 Ry16, 183 1992 Kd, 61 1992

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. Burbine Index More Information 356 Index 1950 DA, 205, 269 single scattering, 142, 143, 144, 145 1979 VA, 230 visual Bond, 7 1991 RY16, 183 visual geometric, 7, 27, 28, 163, 185, 189, 190, 1992 KD, 61 191, 192, 192, 253 1992 QB1, 233, 234 Alexandra, 59 1993 FW, 234 altitude, 49 1994 JR1, 239, 275 Alvarez, Luis, 258 1999 JU3, 61 Alvarez, Walter, 258 1999 RL95, 183 amino acid, 81 1999 RQ36, 61 ammonia, 223, 301 2000 DP107, 274, 304 amoeboid olivine aggregate, 83 2000 GD65, 205 Amor, 251 2001 QR322, 232 Amor group, 251 2003 EH1, 107 Anacostia, 179 2007 PA8, 207 Anand, Viswanathan, 62 2008 TC3, 264, 265 Angelina, 175 2010 JL88, 205 angrite, 87, 101, 110, 126, 168 2010 TK7, 231 Annefrank, 274, 275, 289 2011 QF99, 232 Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET), 71 2012 DA14, 108 Antarctica, 69–71 2012 VP113, 233, 244 aphelion, 30, 251 2013 TX68, 64 APL, 275, 292 2014 AA, 264, 265 Apohele group, 251 2014 RC, 205 Apollo, 179, 180, 251 Apollo group, 230, 251 absorption band, 135–6, 137–40, 145–50, Apollo mission, 129, 262, 299 163, 184 Apophis, 20, 269, 270 acapulcoite/ lodranite, 87, 90, 103, 110, 168, 285 Aquitania, 179 Achilles, 232 Arecibo Observatory, 206 achondrite, 84, 86, 116, 187 Aristarchus, 29 primitive, 84, 86, 103–4, 287 Asporina, 177 Adamcarolla, 62 asteroid chronology function, 262 Adeona family, 198 Asteroid Zoo, 54 Aeternitas, 177 Astraea, 53 Agnia family, 170, 198 Astronautica, 61 AKARI satellite, 192 Aten, 251 alabandite, 76, 101 Aten group, 251 Alauda family, 198 Atira, 251 albedo, 7, 21, 27, 185–6 Atira group, 251 Bond, 7, 8, 9, 28, 189 atmosphere, 1, 3, 8, 43, 66, 68, 265 geometric, 7 A- type, 163, 165, 167, 169, 170, 177–8, 192 356 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. -

Taxonomy of Trans-Neptunian Objects and Centaurs As Seen from Spectroscopy? F

A&A 604, A86 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201730933 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Taxonomy of trans-Neptunian objects and Centaurs as seen from spectroscopy? F. Merlin1, T. Hromakina2, D. Perna1, M. J. Hong1, and A. Alvarez-Candal3 1 LESIA – Observatoire de Paris, PSL Research University, CNRS, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Astronomy, Kharkiv V. N. Karin National University, Sumska Str. 35, 61022 Kharkiv, Ukraine 3 Observatorio Nacional, R. Gal. Jose Cristino 77, 20921-400 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Received 4 April 2017 / Accepted 19 May 2017 ABSTRACT Context. Taxonomy of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs has been made in previous works using broadband filters in the visible and near infrared ranges. This initial investigation led to the establishment of four groups with the aim to provide the mean colors of the different classes with possible links with any physical or chemical properties. However, this taxonomy was only made with the Johnson-Cousins filter system and the ESO J, H, Ks filters combination, and any association with other filter system is not yet available. Aims. We aim to edit complete visible to near infrared taxonomy and extend this work to any possible filters system. To do this, we generate mean spectra for each individual group, from a data set of 43 spectra. This work also presents new spectra of the TNO (38628) Huya, on which aqueous alteration has been suspected, and the Centaur 2007 VH305. -

The Kuiper Belt: What We Know and What We Don’T

The Kuiper Belt: What We Know and What We Don’t David Jewitt, UCLA, September 2012 The best indication of the significance of the Kuiper belt lies in its multiple connections to other aspects of the Solar system. The dust in the Zodiacal cloud, the rocks in the meteor streams, the nuclei of comets, the Centaurs, perhaps also the irregular moons of the planets and the Trojans that lead and trail planets in their orbits, are all related to the parent population in the Kuiper belt. Further afield, the dusty debris disks of other stars are likely produced by collisional shattering of parent bodies in unseen Kuiper belts about them. Because of these many connections, Kuiper belt science has already had significant impact on the study of the contents, origin and evolution of the Solar system, and on understanding the Solar system in the context set by other stars. While we know much more than we used to, we still don’t know many things about the Kuiper belt. The Solar system formed from a flattened, rotating disk of gas and dust, itself produced by gravitational collapse from the interstellar medium. The explosion of a nearby massive star, a “supernova”, may have provided the initial compression causing the cloud to collapse, as suggested by the products of decay of short-lived radioactive elements (esp. 26Al) embedded in meteorites (Lee et al. 1977, Dauphas and Chaussidon 2011). Planets formed quickly in the dense inner portions of this disk but the process of growth in the rarefied outer regions was very slow. -

Atmospheres and Surfaces of Small Bodies and Dwarf Planets in the Kuiper Belt

EPJ Web of Conferences 9, 267–276 (2010) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201009021 c Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2010 Atmospheres and surfaces of small bodies and dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt E.L. Schallera Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Abstract. Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) are icy relics orbiting the sun beyond Neptune left over from the planetary accretion disk. These bodies act as unique tracers of the chemical, thermal, and dynamical history of our solar system. Over 1000 Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) and centaurs (objects with perihelia between the giant planets) have been discovered over the past two decades. While the vast majority of these objects are small (< 500 km in diameter), there are now many objects known that are massive enough to attain hydrostatic equilibrium (and are therefore considered dwarf planets) including Pluto, Eris, MakeMake, and Haumea. The discoveries of these large objects, along with the advent of large (> 6-meter) telescopes, have allowed for the first detailed studies of their surfaces and atmospheres. Visible and near-infrared spectroscopy of KBOs and centaurs has revealed a great diversity of surface compositions. Only the largest and coldest objects are capable of retaining volatile ices and atmospheres. Knowledge of the dynamics, physical properties, and collisional history of objects in the Kuiper belt is important for understanding solar system formation and evolution. 1 Introduction The existence of a belt of debris beyond Neptune left over from planetary accretion was proposed by Kuiper in 1951 [1]. Though Pluto was discovered in 1930, it took over sixty years for other Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) to be detected [2] and for Pluto to be recognized as the first known member of a larger population now known to consist of over 1000 objects (Fig.