Do Blue Crab Spawning Sanctuaries in North Carolina Protect the Spawning Stock?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

Manteo Harbor Report

A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION OF SUBMERGED LANDS AFFECTED BY THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Manteo, North Carolina Conducted By Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Richard W. Lawrence, Head Leslie S. Bright Mark Wilde-Ramsing Report Prepared by Mark Wilde-Ramsing November, 1983 Abstract Field investigations of the submerged bottom lands at Manteo, North Carolina were carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources. The purpose of these investigations was to identify historically and/or archaeologically significant cultural materials lying within the area to be affected by construction of a bridge and canal system and berthing area proposed for the 400th Anniversary Celebration (1984 to 1987) on Roanoke Island. Initially, a systematic survey of the project area was performed using a proton precession magnetometer to isolate magnetic disturbances, any of which might be generated by cultural material. Following this, a diving and probing search was conducted on isolated magnetic targets to determine the source. With the exception of the remains of a sunken vessel, Underwater Site #0001ROS, all magnetic disturbances were attributed to cultural debris of recent origin (twentieth century) and were determined historically and archaeologically insignificant. Recommendations for the sunken vessel located on the south side of the proposed berthing area are (1) complete avoidance of the site during construction activities, or (2) further -

The Carolina

The Carolina RealEstateView A quarterly service for buyers and owners of Outer Banks real estate Winter 2012 OBX Bridges Update IN THIS ISSUE: With so much water in our area, bridges have an added OBX Bridges importance to the OBX. Just three months are needed to complete the Big Bluefin Tuna! new bridge over a canal in Southern OBX Market Update Shores. This new bridge will allow Listings larger boats through while saving Chicahauk residents time on their Smart Phone Searches trips to goods and services. Work was well underway in mid- Neighborhood Values January on the Chicahauk Bridge. The mid-Currituck Bridge is one step Coastal Studies Leader closer to reality! According to the NC Transportation Authority the Calendar of Events Final Environmental Impact Study was completed early this year and they hope to start construction before the end of this year. When or if this bridge is completed, it will save everyone hours of time! Big bluefin are here! Local fishermen know fishing for different Corolla species is cyclical (kind of like the real estate Ocean Front business). Right now there is a tremendous Bargain! boom in blue fin tuna! According to Captain David Daniels of the Seaducer the largest biomass of bluefin he’s ever seen is off Capt. Dave with a bluefin! Oregon Inlet right now. He recently said, “Anglers in the waters off Virginia Beach to Hatteras are hooking these fish ranging in size from 200 lbs. to 350 lbs. with a few giants mixed in.” For more information on catching one of these fish, contact David at [email protected] This beautiful property is OBX Real Estate Market Update the best priced ocean The good news for sellers is there are buyers looking for OBX front home in Corolla. -

Charles Creek Flooding Mitigation Plan Waterfront

QUALIFICATIONS TO PROVIDE CHARLES CREEK FLOODING MITIGATION PLAN AND AUGUST 17, 2017 WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Section I – Cover/Introductory Letter 17 August 2017 Mr. Matthew Schelly, AICP, CZO Director of Community Development, Community Development Department 306 E. Colonial Avenue Elizabeth City, NC 27909 Reference: Request for Qualifications – Charles Creek Flooding Mitigation Plan and Waterfront Master Plan Dear Mr. Schelly: Elizabeth City’s waterfront is one of its most important assets, helping to drive your economy with marine‐ related activities and provide tourists with the amenities that keep them coming back. As such, it is important to develop the right plan to maximize the waterfront’s value to the City and its citizens. To best meet your goals, it is important to select a consultant with the experience and expertise you can trust to deliver a project that meets your needs, on your schedule, and within your budget. As one of the largest waterfront‐focused firms in the county, Moffatt & Nichol, Inc. stands ready to complete this important project and implement your vision for your waterfront’s future. Moffatt & Nichol brings you: Local Waterfront Knowledge and Focus. Operating in Raleigh since 1981, Moffatt & Nichol is a leading provider of waterfront planning and design. Project Manager Scott Lagueux joined the firm in 2016, and brings 23 years of experience in urban and commercial waterfront projects, having completed them in more than 70 countries worldwide. High‐quality Floodplain Services: We also offer the stormwater resources you need in our Raleigh office to complete Charles Creek Flooding Mitigation Plan, enabling us to meet both of your core project needs with predominantly North Carolina‐based resources. -

Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place

ABSTRACT LEE, GABRIEL FRANCIS. Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place. (Under the direction of Matthew Morse Booker.) This thesis is an environmental history of the North Carolina Outer Banks that combines cultural history, political economy, and conservation science and policy to explain the entanglement of constructions, uses, and claims over the land that created by the late 20th century a complex, contested, and national place. It is in many ways a synthesis of the multiple disparate stories that have been told about the Outer Banks—narratives of triumph or of decline, vast potential or strict limitations—and how those stories led to certain relationships with the landscape. At the center of this history is a declension narrative that conservation managers developed in the early 20th century. Arguing that the landscape that they saw, one of vast sand-swept and barren stretches of island with occasional forests, had formerly been largely covered in trees, conservationists proposed a large-scale reclamation project to reforest the barrier coast and to establish a regulated and sustainable timber industry. That historical argument aligned with an assumption among scientists that barrier islands were fundamentally stable landscapes, that building dunes along the shore to generate new forests would also prevent beach erosion. When that restoration project, first proposed in 1907, was realized under the New Deal in the 1930s, it was followed by the establishment of the first National Seashore Park at Cape Hatteras in 1953, consisting of the outermost islands in the barrier chain. The idea of stability and dune maintenance continued to frame all landscape management and development policies throughout the first two decades after the Park’s creation. -

Read Penne Smith's Research on Island Farm

ILLUSTRATIONS TO TEXT Fig. 1: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House, front elevation, ca. 1945 (at present site; original porch removed). Paneled door is original. Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. Fig. 2: Meekins Homeplace, side elevation ca. 1915. D. Victor Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC Fig. 3: Christaina (“Crissy”) Bowser, ca. 1910. D. Victor Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. N.B. The simple stoop entrance and rough board-and-batten exterior in the background; this has been assumed to have been Crissy Bowser’s cabin on the Etheridge Farm. Fig. 4: Thomas A. Dough, Grave Marker. Etheridge Family Cemetery, Manteo, NC (Penne Smith, 1999 photograph) Fig. 5: Detail of Thomas A. Dough Grave Marker (Penne Smith, 1999 photograph) Fig. 6: Aufustus H. Etheridge Business Card, 1907. Etheridge Family Collection, Outer Banks Conservationists, Inc. Fig. 7: Front elevation of Etheridge House, May 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) Fig. 8: 1890s rear ell of Etheridge House, May 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) Fig. 9: Capt. L. J. Pugh House, Wanchese, NC, July 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) This graceful Victorian farmhouse may have been what the Etheridge 1890s rrenovation aspired to. Fig. 11: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House, front and side elevations, ca. 1940. Roger Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC Fig. 13: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House,rear and side elevations, ca. 1940. Roger Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. N.B. the door surround at the side elevation. Fig. 14: United States Coast Guard, 1957 aerial map of Roanoke Island, detail of Etheridge Homeplace farmstead. Cartography Division, National Archives, College Park, MD Fig. -

Currituck National Wildlife Refuge

Currituck National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region November 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN CURRITUCK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Currituck County, North Carolina U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia November 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN I. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 2 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 3 Refuges of the Ecosystem ............................................................................................................4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 4 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives -

Contents Chapter 5 Outer Banks

Contents Chapter 5 Outer Banks ............................................................................................................................... 2 5.1 General Description ...................................................................................................................... 2 5.2 Population and Land Cover ........................................................................................................... 2 5.3 Biological Health and Ambient Water Quality .............................................................................. 2 5.4 Shellfish Sanitation and Recreation Water Quality....................................................................... 3 5.4.1 Potential Pollution Sources ................................................................................................... 3 5.4.2 Water Quality and Shellfish Harvesting ................................................................................ 4 5.5 How to Read the Watershed (HUC 10) Sections ........................................................................... 6 5.6 North Landing River (HUC: 0301020512) ...................................................................................... 8 5.7 Sand Ridge-Bodie Island (HUC: 0301020517) ............................................................................... 8 5.8 Currituck Sound (HUC: 0301020513) ............................................................................................ 8 5.8.1 Dowdys Bay (Poplar Branch Bay) [AU# 30-1-15b] ............................................................... -

Mid-Currituck Bridge Study Statement of Purpose And

MID-CURRITUCK BRIDGE STUDY STATEMENT OF PURPOSE AND NEED WBS Element: 34470.1.TA1 STIP NO. R-2576 CURRITUCK COUNTY DARE COUNTY Prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff 909 Aviation Parkway, Suite 1500 Morrisville, North Carolina 27560 for the Raleigh, North Carolina October 2008 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents 1.0 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION ................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Area ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Project Needs........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Project Purpose ....................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Project Description................................................................................................. 7 1.4.1 Setting and Land Use................................................................................. 7 1.4.2 Project History ............................................................................................ 8 1.5 System Linkage..................................................................................................... 11 1.5.1 Existing Road Network ........................................................................... 11 1.5.2 Sidewalks, Bicycles Routes, and Pedestrian Movements ................... 12 1.5.3 Modal Interrelationships........................................................................ -

Oregon Inlet 2011

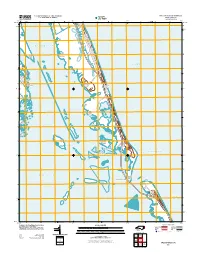

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ! OREGON INLET QUADRANGLE ! ! U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ! NORTH CAROLINA ! ! ! 7.5-MINUTE SERIES R O A N O K E S O U N D ! ! 75°37'30" 35' ! 32'30" 75°30' " H! 4 4 î 4 000m 4 4 "î 4H H 4 4 4 4 " FEET î 3 030 000 35°52'30" 44 E 45 46 47 48 49 50 52 53 54 35°52'30" 3970 3970000mN H " î î H " H H " " " H H " H " î " H " H" î î H " " HH " 790 000 î î " î î H " î " " î " H " H î " H H " î î H " î " H î î î î " î " î î î " î H H H î H " FEET H " " " î " H " H î H Hî H î H " H H î î î î î H " H î î H " " " î H H H î " î H î î î " H H" " H î H H" î î î " " î H î H " H " î î " H "î î " î " î " î H î H H î "H " H î " " H " î " î H "î " H H" " " " î H î " H "H î " H î î H H H " î " î î î î î HH HH î î H H " H H " H î î î î î " " H " " î H H " î î H î H î î " H î " "" H " H" H "H " H î î " î H " " " " H î 39 î î H H " " " H î H " î 69 H 39 " H H î " " î H " " î " î H H H "" H " H " HH î 69 î H î H î H H î î î H î H H H " " H " H î î " " î î î " î H H " î " " î H" " " " î H «¬12 R O A N O K E S O U N D " " H " H " î " î "" H "î " H H î H H î H -

Coastal Processes and Conflicts: North Carolina͛s Outer Banks

Coastal Processes and Conflicts: EŽƌƚŚĂƌŽůŝŶĂ͛ƐKƵƚĞƌĂŶŬƐ A Curriculum for Middle and High School Students Stanley R. Riggs Dorothea V. Ames Karen R. Dawkins North Carolina Sea Grant North Carolina State University Campus Box 8605 Raleigh, NC 27695-8605 The seam where continent meets ocean is a line of constant change, where with every roll of the waves, every pulse of the tides the past manifestly gives way to the future. There is a sense of time and of growth and decay, life mingling with death. It is an unsheltered place, without pretense. The hint of forces beyond control, of days before and after the human span, spell out a message ultimately important, ultimately learned. David Leveson (1972) THE AUTHORS Dr. Stanley R. Riggs, Ms. Dorothea Ames, and Dr. Karen Dawkins are affiliated with East Carolina University. Dr. Riggs is distinguished research professor in the Department of Geological Sciences, and Ms. Dorothea Ames is research instructor in the Department of Geological Sciences. Dr. Karen Dawkins is director of the Center for Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education in the College of Education. Drowning the North Carolina Coast: Sea-Level Rise and Estuarine Dynamics, a NC Sea Grant publication authored by Riggs and Ames, was the source for much of the scientific content and many of the figures. The authors offer special thanks to the hardy band of teachers and students who investigated their sites and contributed their ideas and expertise to this curriculum product. Students Teachers Schools Julia Alspaugh Tim Phillips Ravenscroft HS, Raleigh Eva Lee Martha Buchanan Freedom HS, Burke County Andrew McKay Marie McKay Ashbrook HS, Gaston County Patrick Nelli Ben Earle Ashbrook HS, Gaston County Lizzie Partusch Clyda Lutz W.