1870 Cape Hatteras Light Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge Refuge Facts ■ Endangered and threatened ■ Established: April 12, 1938. species include loggerhead sea turtles and piping plovers. Both ■ Size: Originally: 5,915 acres species nest on the refuge. (land), 25,700 acres (Proclamation Boundary Waters). Currently: Financial Impacts 4,655 acres. ■ Administered by Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. Pea ■ Administered by Alligator River Island has no assigned staff or National Wildlife Refuge. budget. photo: USFWS photo: ■ Located on the north end of ■ One employee reports for duty Hatteras Island, a coastal barrier to Pea Island National Wildlife island and part of a chain of islands Refuge on a daily basis. known as the Outer Banks. ■ Numerous volunteers devote ■ Approximately 13 miles long (north approximately 25,000 hours each to south) and ranges from a quarter year to Pea Island. mile to one mile wide (from east to west). ■ 2.7 million visitors annually. ■ Location: 10 miles south of Nags ■ Known as a “Birder’s Paradise”; Head, NC on NC Highway 12. birders are among the most photo: USFWS photo: affluent eco-tourists. Other visitors ■ The Comprehensive Conservation include paddlers, fishermen, and Plan for Pea Island National photographers. Wildlife Refuge was completed July 17, 2006. Refuge Goals ■ Protect, maintain, and enhance Natural History healthy and viable populations ■ Area was historically used for of indigenous migratory birds, market waterfowl hunting, hunt wildlife, fish, and plants including clubs, commercial fishing, farming, federal and state threatened and and livestock operations. photo: USFWS photo: endangered species. ■ Refuge is comprised of ocean ■ Restore, maintain, and enhance the beach, dunes, upland, fresh and health and biodiversity of barrier brackish water ponds, salt flats, and island upland and wetland habitats salt marsh. -

Beacons of the Coast

National Seashore National Park Service Cape Lookout U.S. Department of the Inerior Beacons of the Coast Over a century ago, mariners travelling along the Atlantic coast encountered dangerous shoals and treacherous storms. Their guides were the beacons of light produced by lighthouses which helped mariners navigate the perilous coastline. For mariners traveling along the North Carolina coast, seven lighthouse beacons were constructed to guide them through an area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” Hundreds of shipwrecks occurred due to the dangers of this area. Today, the ships traveling the coast use modern tools such as radar and sonar. The beacons continue to operate, standing as a reminder of the hardships encountered by our ancestors to help settle the country. These seven lighthouses found on the North Carolina coast stand as pieces of our past. CURRITUCK BEACH LIGHTHOUSE This lighthouse was constructed from 1874 - 1875, and it lit the last dark spot on the Carolina coast between the Cape Fear lighthouse in Virginia and Bodie Island. The red brick lighthouse rises 158 feet above sea level. Unlike many other lighthouses that received distinctive day marks, Currituck was not painted. But its red brick is unique on the Carolina coast. It has a short light signal: 5 seconds on, 15 seconds off. There is a Fresnel lens still working in the lighthouse and it is activated from dusk to dawn. Currituck Lighthouse is open 10-6 daily from Easter to Thanksgiving weekend. You can walk to the top of the lighthouse. BODIE ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE This was the third lighthouse to be built on Bodie Island (pronounced “body”) and was constructed in the early 1870’s. -

12 Years of Sand Bypassed from Oregon Inlet to Pea Island)

0058423 Impacts of Dredging and Inlet Bypassing on the Inter-tidal Ecology of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge (12 Years of Sand Bypassed from Oregon Inlet to Pea Island) Dennis Stewart US Fish and Wildlife Service and Robert Dolan University of Virginia 1 0058424 2 0058425 3 0058426 4 0058427 5 0058428 6 0058429 • Cape Hatteras National Seashore • Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge • National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 • Compatibility Determination 7 0058430 Fundamental Questions • Anticipated physical impacts to beach? • What are the ecological implications? • Compatible with mission and purpose? 8 0058431 9 0058432 Table 1. Statistical Summary Location Sand Size S.D. Heavy Minerals Percent Fine Sand (In mm) (Dark Minerals) (‹0.25mm) Pea Island Swash zone 0.57mm 1.3 2.5% 32% Oregon Inlet 0.26mm 2.4 11% 50% Spit Ocean Bar 0.45mm 3.3 6% 33% Oregon Inlet 0.22mm 2.0 10% 60% Channel 10 0058433 11 0058434 Significant Impacts • 1. Burial (>4cm without wave runup) • 2. Finer grains & high % heavy mineral • Degree of impact correlated with: – Frequency – Volume –Placement Trend in mean grain size from 1990-2002, mid swash zone, Pea Island, NC. 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 R = 0.68 2 0.4 R = 0.46 0.3 0.2 Average mean grain size (mm) size meanAverage grain 0.1 0 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Dredge Disposal Data 3 1200000 Hopper Dredge 1000000 Pipeline Dredge 800000 600000 400000 200000 0 Volume of sand deposited y Volume deposited sand of 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 12 0058435 Trend in heavy mineral content of the Mid-Swash Zone 1992-2002 18.00 16.00 14.00 12.00 10.00 R = 0.81 8.00 R2 = 0.65 6.00 Mineral Abundance (%) 4.00 2.00 0.00 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Dredge Disposal Data ) 3 1200000 Hopper Dredge 1000000 Pipeline Dredge 800000 600000 400000 200000 0 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Volume of sand deposited (y Trend of decline in Emerita counts taken from 1990-2002 along Pea Island, NC. -

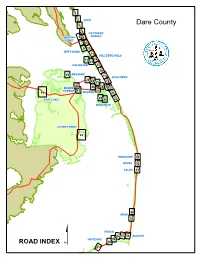

Road Index Books

1 2 DUCK 3 Dare County 4 SOUTHERN SHORES MARTINS 5 6 POINT 7 8 9 10 KITTY HAWK 11 KILL DEVIL HILLS 14 12 13 COLINGTON 15 16 45 MASHOES 17 NAGS HEAD 23 24 25 18 42 MANNS 26 28 19 20 HARBOR 43 27 46 MANTEO 21 EAST LAKE 29 30 22 WANCHESE STUMPY POINT 44 RODANTHE 31 WAVES 32 SALVO 33 34 AVON 35 FRISCO 38 37 36 BUXTON HATTERAS 39 ROAD INDEX $ 40 41 N BAUM TRL S BAUM TRL DUCK RD - NC 12 A B STATIONBAY DRIVE MARTIN LANE VIREO WAY QUAIL WAY GANNET WAXWING LANE LANE WAXWING GANNET COVE COURT HERON LN BLUE RUDDY DUCK LN PELICAN WAY TERNLN ROYAL LANE BUNTING SHEARWATER WAY BUNTING BUNTINGLN WAY C D SKIMMER WAY WAY SKIMMER OYSTER CATCHER LN SANDPIPERCOVE OCEAN PINES DRIVE FLIGHT DR OCEAN BAY BLVD CLAY ST ACORN OAK AVE SOUND SEA AVE MAPLE WILLOW DRIVE ELM DRIVE CYPRESS DRIVE DRIVE CEDAR DRIVE HILLSIDE COURT CARROL DR - SR 1408 ° Duck 1 CYPRESS CEDAR DRIVE WILLOW DRIVE DRIVE MAPLE DRIVE CARROL DR - SR 1408 CAFFEYS HILLSIDE COURT COURT SEA TERN DRIVE QUARTERDECK DRIVE TRINITIE DR MALLARD DRIVE COURT RENE DIANNE ST FRAZIER COURT A OLD SQUAW DRIVE SR 1474 BUFFELL HEAD RD - SR 1473 SPRIGTAIL DRIVE SR 1475 CANVAS BACK DRIVE SR 1476 WOOD DUCK DRIVE SR 1477 PINTAIL DRIVE SR 1478 WIDGEON DR - SR 1479 BALDPATE DRIVE WHISTLING B SWAN DR N SNOW GEESE DR S SNOW GEESE DR SPYGLASS ROAD SANDCASTLE SPINDRIFTLANE COURT COURT PUFFER NOR BANKS DR SAILFISH SNIPE CT COURT WINDSURFER COURT SUNFISH COURT DUCK ROAD - NC 12 C § DUCK VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPT D SANDY RIDGE ROAD 2 TOPSAIL COURT SPINNAKER MAINSAILCOURT COURT FORESAIL COURT WATCHSHIPS DR BARRIER ISLAND STATION Duck -

State Historic Preservation Office Peter B

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Peter B. Sandbeck, Administrator Beverly Eaves Perdue, Governor Office of Archives and History Linda A. Carlisle, Secretary Division of Historical Resources Jeffrey J. Crow, Deputy Secretary David Brook, Director March 20, 2009 MEMORANDUM To: Mary Pope Furr Historic Architecture Group, HEU, PDEA NC Department of Transportation From: Peter Sandbeck Re: Mid-Cm-rituck Bridge Project, R-2576, Currituck and Dare Counties, CH 94-0809 We are in receipt of the March 11, 2009, letter from Courtney Foley, transmitting her Historic Architectural Resources Survey Report Addendum for the above referenced undertaking. Having reviewed the addendum, we offer the following comments. As noted in the report, the State Historic Preservation Office concurred on April 30, 2008 that the following properties are listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Girrituck Beach Light Station (CK1 — NR) Whalehead Club (CK5 — NR) Corolla Historic District (CK97 — DOE) Ellie and Blanton Saunders Decoy Workshop (CK99 — DOE) Dr. W. T. Griggs House (CK 103 — DOE) Currituck Sound Rural Historic District (DOE) Cle-01 09- Daniel Saunders House (DOE) (2,140 101 Samuel McHorney House (DOE) G4-00111 Coinjock Colored School (DOE) Oy_011,, On June 2, 2008, after further discussion with your staff, we also concurred that the Center Chapel A_ME Zion Church is eligible for the National Register. We also concur that the five properties in the subject addendum are eligible for listing in the National Register. They are: (Former) Grandy School (CK 40 — NR 1998) Jarvisburg Colored School (CK 55 — SL 1999) Dexter W. -

Blackbeard and Shipwrecks - Ocracock Inlet

Blackbeard and Shipwrecks - Ocracock Inlet This image depicts part of a map called Ocacock Inlet, including the following printed notation: "A 1733 chart of Ocracoke Inlet by Edward Moseley." (Note the different spellings of the inlet's name, including today's "Ocracoke"). The inlet, an estuary situated in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, connects the Atlantic Ocean to Pamlico Sound. It also separates the islands of Portsmouth and Ocracoke. This place was the scene of a battle, in 1718, between the British Royal Navy (led by Lieutenant Robert Maynard) and Edward Teach (the pirate known as "Blackbeard"). At the end of the fighting, the pirates had lost (and Blackheard’s severed head was on the bowsprit of Maynard's ship). This map is still an important resource. It allows modern researchers to examine how the Inlet has changed during hundreds of years. It also helps to explain why there have been so many shipwrecks in the area. We learn about that from NOAA (the U.S. federal government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration): Ocracoke Inlet, North Carolina, is shown on Edward Moseley's map of 1733. This map, when compared with other historic maps, enabled researchers to determine how the inlet has changed over several hundred years. Some shipwrecks are no longer in or near the present inlet. The map clearly shows the obstructions at the mouth of the inlet that caused numerous ships to run aground. In fact, there have been so many shipwrecks in this area that we now have an “Ocracoke Shipwreck Survey.” Ocean Explorer, part of NOAA’s website, tells us about the survey: An extraordinary increase in the number of identified shipwreck sites since the beginning of the Ocracoke Shipwreck Survey has led to the development of a Geographic Information System (GIS), which can provide overlays of data by location, date, ship type, and other criteria. -

Oregon Inlet Opened in 1846 As Water Rushed from the Sound to the Ocean

Oregon Inlet opened in 1846, when a big hurricane along the Outer Banks caused water to rush from the sound to the ocean. Since that time, the inlet has migrated steadily south at a rate of around 100 feet per year. A good measure of the inlet’s journey is the Bodie Island Lighthouse, which once stood at the margin of the inlet but is now 3 miles away. In 1962, the Bonner Bridge replaced the ferry that shuttled people and cars across Oregon Inlet. Construction of the bridge, with its high fixed-span, instantly stopped the long history if inlet migration. But sand continued to pour into the inlet from the north, the driving force behind the inlet’s southerly migration, creating ever-expanding navigation and dredging problems. After 40 years, the Bonner Bridge is rapidly deteriorating and two possible replacement alternatives are being evaluated: A bridge immediately parallel to the current bridge and a 17 mile-long bridge that would extend into Pamlico Sound, run along the backside of Pea Island and connect to Hatters Island at Rodanthe. The initial cost of constructing the Pamlico Sound Bridge is much higher than that of the Parallel Bridge. But the overall long-term costs of a Parallel Bridge greatly exceed those of the Pamlico Sound Bridge. This is because the Parallel Bridge requires the continued protection and maintenance of State Highway 12 on Pea Island. Over time, as the shoreline erodes back in response to a rising sea level, the cost of stabilizing Pea Island will become higher. Construction impacts to wetlands and sea grass beds are essentially the same for each bridge. -

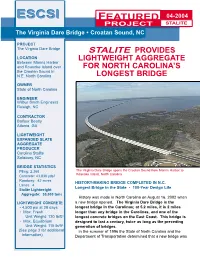

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Station Ocracoke, North Carolina Coast Guard Station #187

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Station Ocracoke, North Carolina Coast Guard Station #187 Coast Guard Station Ocracoke Original At Ocracoke, N.C.,, on northwest tip of Ocracoke Island, 1/2 mile Location: north of Ocracoke Light; 35-06' 55"N x 75-59' 20"W Date of 1904 Conveyance: First station was built in 1904; second station was built during Station Built: World War II Fate: Still in operation -- see below Remarks: The current (2004) Coast Guard Station Ocracoke (small) is located on the southern end of Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. The Station has a compliment of 1 boat crew and 1 First Class Boatswain Mate as the supervisor. The boat crew is assigned to the unit on a rotating basis from Station Hatteras Inlet, it's parent unit. The station building is a modular structure constructed in the 1970s and is situated on one acre of National Park Service land. The building contains berthing for 6 duty watchstanders, a galley, and a communications center. 1 Station Ocracoke is a sub-unit and comes under the administrative and operational control of Station Hatteras Inlet. As a multi-mission unit, Station Ocracoke conducts search and rescue, boating safety, law enforcement, and marine environmental protection operations. A boat crew is available 24 hours a day and responds to more than 100 calls for assistance annually. The station's Area of Responsibility (AOR) includes more than 1350 square nautical miles of Atlantic Ocean, one third of the Pamlico Sound, and half of Ocracoke Island. To cover this area and respond to calls for assistance in any type of weather, the station is equipped with a 44-ft Motor Life Boat, and a 21-ft Motor Life Inflatable. -

BUILDING Bridges to a Better Economy Viewfinder Ll 2007 Fa Eastthe Magazine of East Carolina University

2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy BUILDING BrIDGes to a better economy vIewfINDer 2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 feaTUres BUilDing BriDges 12 Creating more jobs is the core of the university’s newBy Steve focus Tuttle on economic development. From planning a new bridge to the Outer Banks to striking new partnerships with relocating companies, ECU is helping the region traverse troubled waters. TUrning The PAGE 18 Shirley Carraway ’75 ’85 ’00 rose steadily in her careerBy Suzanne in education Wood from teacher to principal to superintendent. “I’ve probably changed my job every four or five years,” she says. 18 22 “I’m one of those people who like a challenge.” TeaChing sTUDenTs To SERVE 22 Professor Reginald Watson ’91 is determined toBy walkLeanne the E. walk,Smith not just talk the talk, about the importance of faculty and students connecting with the community. “We need to keep our feet in the world outside this campus,” he says. FAMILY feUD 26 As another football game with N.C. State ominouslyBy Bethany Bradsher approaches, Skip Holtz is downplaying the importance of the contest. And just as predictably, most East Carolina fans are ignoring him. DeParTMeNTs froM oUr reaDers 3 The eCU rePorT 4 26 FALL arTs CalenDar 10 BookworMs PiraTe naTion Dowdy student stores stocks books 34 for about 3,500 different courses and expects to move about one million textbooks into the hands of students during the hectic first CLASS noTes weeks of fall semester. Jennifer Coggins and Dwayne 37 Murphy are among several students who worked this summer unpacking and cataloging thousands of boxes of new books. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

Supplemental Article to Where Is the Lost Colony?

Challenges to living by the sea A supplement to the serial story, Where is The Lost Colony? written by Sandy Semans, editor, Outer Banks Sentinel The thin ribbon of sand that forms the chain of islands known as the Outer Banks is bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the west by the sounds. The shapes of the islands and the inlets that run between them continue to be altered by hurricanes, nor’easters and other weather events. Inlets that often proved to be moving targets created access to the ocean and the sounds. Inlets were formed and then later filled with sand and disappeared. Maps of the coastline show many places named “New Inlet,” although currently there is no inlet there. The one exception has been Ocracoke Inlet between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands. Marine geologists estimate that the existing inlet — with some minor changes — has been in place for at least 2500 years. During the English exploration of the 1500’s, most likely the ships came through this inlet, making it a long sail to Roanoke Island. At that time, there was a small shallow inlet between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, but the shallow inlet probably was avoided for fear of going aground. By the early 1700s, this inlet had filled in, and the two became just one long island. But in 1846, a hurricane created two major inlets. One, now called Oregon Inlet, sliced through the sand, leaving today’s Pea Island to the south and Bodie Island to the north. And a second inlet, now known as Hatteras Inlet, once again separated Hatteras Island from Ocracoke Island.