Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

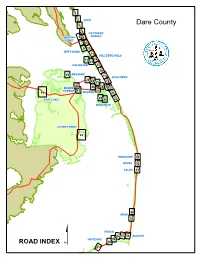

Road Index Books

1 2 DUCK 3 Dare County 4 SOUTHERN SHORES MARTINS 5 6 POINT 7 8 9 10 KITTY HAWK 11 KILL DEVIL HILLS 14 12 13 COLINGTON 15 16 45 MASHOES 17 NAGS HEAD 23 24 25 18 42 MANNS 26 28 19 20 HARBOR 43 27 46 MANTEO 21 EAST LAKE 29 30 22 WANCHESE STUMPY POINT 44 RODANTHE 31 WAVES 32 SALVO 33 34 AVON 35 FRISCO 38 37 36 BUXTON HATTERAS 39 ROAD INDEX $ 40 41 N BAUM TRL S BAUM TRL DUCK RD - NC 12 A B STATIONBAY DRIVE MARTIN LANE VIREO WAY QUAIL WAY GANNET WAXWING LANE LANE WAXWING GANNET COVE COURT HERON LN BLUE RUDDY DUCK LN PELICAN WAY TERNLN ROYAL LANE BUNTING SHEARWATER WAY BUNTING BUNTINGLN WAY C D SKIMMER WAY WAY SKIMMER OYSTER CATCHER LN SANDPIPERCOVE OCEAN PINES DRIVE FLIGHT DR OCEAN BAY BLVD CLAY ST ACORN OAK AVE SOUND SEA AVE MAPLE WILLOW DRIVE ELM DRIVE CYPRESS DRIVE DRIVE CEDAR DRIVE HILLSIDE COURT CARROL DR - SR 1408 ° Duck 1 CYPRESS CEDAR DRIVE WILLOW DRIVE DRIVE MAPLE DRIVE CARROL DR - SR 1408 CAFFEYS HILLSIDE COURT COURT SEA TERN DRIVE QUARTERDECK DRIVE TRINITIE DR MALLARD DRIVE COURT RENE DIANNE ST FRAZIER COURT A OLD SQUAW DRIVE SR 1474 BUFFELL HEAD RD - SR 1473 SPRIGTAIL DRIVE SR 1475 CANVAS BACK DRIVE SR 1476 WOOD DUCK DRIVE SR 1477 PINTAIL DRIVE SR 1478 WIDGEON DR - SR 1479 BALDPATE DRIVE WHISTLING B SWAN DR N SNOW GEESE DR S SNOW GEESE DR SPYGLASS ROAD SANDCASTLE SPINDRIFTLANE COURT COURT PUFFER NOR BANKS DR SAILFISH SNIPE CT COURT WINDSURFER COURT SUNFISH COURT DUCK ROAD - NC 12 C § DUCK VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPT D SANDY RIDGE ROAD 2 TOPSAIL COURT SPINNAKER MAINSAILCOURT COURT FORESAIL COURT WATCHSHIPS DR BARRIER ISLAND STATION Duck -

State Historic Preservation Office Peter B

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Peter B. Sandbeck, Administrator Beverly Eaves Perdue, Governor Office of Archives and History Linda A. Carlisle, Secretary Division of Historical Resources Jeffrey J. Crow, Deputy Secretary David Brook, Director March 20, 2009 MEMORANDUM To: Mary Pope Furr Historic Architecture Group, HEU, PDEA NC Department of Transportation From: Peter Sandbeck Re: Mid-Cm-rituck Bridge Project, R-2576, Currituck and Dare Counties, CH 94-0809 We are in receipt of the March 11, 2009, letter from Courtney Foley, transmitting her Historic Architectural Resources Survey Report Addendum for the above referenced undertaking. Having reviewed the addendum, we offer the following comments. As noted in the report, the State Historic Preservation Office concurred on April 30, 2008 that the following properties are listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Girrituck Beach Light Station (CK1 — NR) Whalehead Club (CK5 — NR) Corolla Historic District (CK97 — DOE) Ellie and Blanton Saunders Decoy Workshop (CK99 — DOE) Dr. W. T. Griggs House (CK 103 — DOE) Currituck Sound Rural Historic District (DOE) Cle-01 09- Daniel Saunders House (DOE) (2,140 101 Samuel McHorney House (DOE) G4-00111 Coinjock Colored School (DOE) Oy_011,, On June 2, 2008, after further discussion with your staff, we also concurred that the Center Chapel A_ME Zion Church is eligible for the National Register. We also concur that the five properties in the subject addendum are eligible for listing in the National Register. They are: (Former) Grandy School (CK 40 — NR 1998) Jarvisburg Colored School (CK 55 — SL 1999) Dexter W. -

Report on Core Sound Shellfish Aquaculture Leasing

MEMORANDUM TO: JOINT LEGISLATIVE COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENTAL OPERATIONS The Honorable Tim Moore, Co-Chair The Honorable Phil Berger, Co-Chair FROM: Mollie Young, Director of Legislative Affairs SUBJECT: Core Sound Oyster Leasing Report DATE: April 7, 2016 Pursuant to Session Law 2015-241, section 14.8, “The Division of Marine Fisheries of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources shall, in consultation with representatives of the commercial fishing industry, representatives of the shellfish aquaculture industry, and relevant federal agencies, create a proposal to open to shellfish cultivation leasing certain areas of Core Sound that are currently subject to a moratorium on shellfish leasing. The Division shall submit a report regarding the plan no later than April 1, 2016, to the Joint Legislative Commission on Governmental Operations.” The attached document satisfies this reporting requirement. If you have any questions or need additional information, please contact me by phone at 919- 707-8618 or via email at [email protected]. cc: John Evans, Chief Deputy Secretary, DEQ Col. Jim Kelley, Acting Director of Marine Fisheries, DEQ Division of Marine Fisheries Report on Core Sound Shellfish Aquaculture Leasing Introduction: Session Law 2015-241, Section 14.8 requires the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries to create a proposal to open to shellfish cultivation leasing certain areas of Core Sound that are currently subject to a moratorium on shellfish leasing. The proposal shall be developed following consultation with representatives of the commercial fishing industry, aquaculture industry, and relevant federal agencies. To develop our proposal, division staff met with the Carteret County Fisheries Association which represents commercial fishing interests, the president of the N.C. -

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT of ENVIRONMENT and NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Water Quality Environmental Sciences Section

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Water Quality Environmental Sciences Section April 2005 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables...........................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures..........................................................................................................................................3 OVERVIEW.............................................................................................................................................4 WHITE OAK RIVER SUBBASIN 01........................................................................................................8 Description .................................................................................................................................8 Overview of Water Quality .........................................................................................................9 Benthos Assessment .................................................................................................................9 WHITE OAK RIVER SUBBASIN 02......................................................................................................11 Description ...............................................................................................................................11 Overview of Water Quality .......................................................................................................12 -

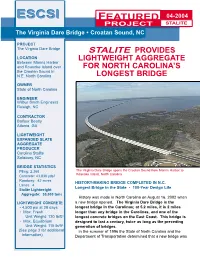

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Life on the Outer Banks an Educator’S Guide to Core and Shackleford Banks

Cape Lookout National Seashore Life on the Outer Banks An Educator’s Guide to Core and Shackleford Banks Sixth Grade Edition Prepared by the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center Funded by a grant from the National Park Service Parks as Classrooms The National Park Service’s Parks as Classrooms program is a nationwide initiative to encourage utilization of the resources of America’s national parks for teaching and learning. A visit to the National Park Service’s homepage (http://www.nps.gov) reveals myriad learning opportunities available to our nation’s students and teachers. Students will discover history and explore nature within the context of a changing world; and yet, within the boundaries of many parks, the hands of time are frozen to allow them a “snapshot” of the past. Parks as Classrooms focuses on bringing learning to life through exciting hands-on, experiential opportunities that are student-friendly, field based, and promote a sense of stewardship of park resources. Cape Lookout’s Classroom Lying just east of the North Carolina mainland are the barrier islands that compose the famed Outer Banks. Cape Lookout National Seashore protects some of the southern-most sections of this barrier island chain. The park covers the long, narrow ribbon of sand running from Ocracoke Inlet in the northeast to Beaufort Inlet in the southwest. The names given to these three barrier islands are Portsmouth Island (Portsmouth Village, although uninhabited, is at the north end of the island), Core Banks (where the Cape Lookout Lighthouse is located near the southern end of the island), and Shackleford Banks. -

BUILDING Bridges to a Better Economy Viewfinder Ll 2007 Fa Eastthe Magazine of East Carolina University

2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy BUILDING BrIDGes to a better economy vIewfINDer 2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 feaTUres BUilDing BriDges 12 Creating more jobs is the core of the university’s newBy Steve focus Tuttle on economic development. From planning a new bridge to the Outer Banks to striking new partnerships with relocating companies, ECU is helping the region traverse troubled waters. TUrning The PAGE 18 Shirley Carraway ’75 ’85 ’00 rose steadily in her careerBy Suzanne in education Wood from teacher to principal to superintendent. “I’ve probably changed my job every four or five years,” she says. 18 22 “I’m one of those people who like a challenge.” TeaChing sTUDenTs To SERVE 22 Professor Reginald Watson ’91 is determined toBy walkLeanne the E. walk,Smith not just talk the talk, about the importance of faculty and students connecting with the community. “We need to keep our feet in the world outside this campus,” he says. FAMILY feUD 26 As another football game with N.C. State ominouslyBy Bethany Bradsher approaches, Skip Holtz is downplaying the importance of the contest. And just as predictably, most East Carolina fans are ignoring him. DeParTMeNTs froM oUr reaDers 3 The eCU rePorT 4 26 FALL arTs CalenDar 10 BookworMs PiraTe naTion Dowdy student stores stocks books 34 for about 3,500 different courses and expects to move about one million textbooks into the hands of students during the hectic first CLASS noTes weeks of fall semester. Jennifer Coggins and Dwayne 37 Murphy are among several students who worked this summer unpacking and cataloging thousands of boxes of new books. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

No One Knows for Sure When the First Europeans Looked Upon Carteret's Barrier Islands

Graves and Shackleford No one knows for sure when the first Europeans looked upon Carteret’s barrier islands. However, an Italian explorer named Giovanni da Verrazzano left what most consider to be the first written description of Core Banks. Sailing northeast from Cape Fear his party of explorers reached the area of Carteret County in 1524. He tried to send a party ashore but the wave action along the beach made this impossible. However, a single sailor did reach the shore where he was greeted by natives who carried him a distance from the surf. The frightened man is reported to have screamed in dismay at this turn of events. He became even more upset when he saw them prepare a large fire. But as soon as he recovered his strength these natives let him return to Verrazzano’s ships. Over the years, from Verrazzano’s report until English settlement in the late 1600s, the Indians reported that there were several shipwrecks along the coast and that some Europeans (probably Spanish) did make it to safety where they lived with the Indians. In 1713 an estimated seven thousand acres, all of Core and Shackleford Banks, was given by the English to a man named John Porter. He held the land only a few years and in 1723 sold it to Enoch Ward and John Shackleford. Known as the Sea Banks, this narrow piece of land stretching from Beaufort Inlet northeastward to Ocracoke Inlet was divided between Shackleford and Ward. Ward got the area north of Cape Lookout, known today as Core Banks while Shackleford gave his name to the area southwest of Lookout to Beaufort Inlet, Shackleford Banks. -

Supplemental Article to Where Is the Lost Colony?

Challenges to living by the sea A supplement to the serial story, Where is The Lost Colony? written by Sandy Semans, editor, Outer Banks Sentinel The thin ribbon of sand that forms the chain of islands known as the Outer Banks is bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the west by the sounds. The shapes of the islands and the inlets that run between them continue to be altered by hurricanes, nor’easters and other weather events. Inlets that often proved to be moving targets created access to the ocean and the sounds. Inlets were formed and then later filled with sand and disappeared. Maps of the coastline show many places named “New Inlet,” although currently there is no inlet there. The one exception has been Ocracoke Inlet between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands. Marine geologists estimate that the existing inlet — with some minor changes — has been in place for at least 2500 years. During the English exploration of the 1500’s, most likely the ships came through this inlet, making it a long sail to Roanoke Island. At that time, there was a small shallow inlet between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, but the shallow inlet probably was avoided for fear of going aground. By the early 1700s, this inlet had filled in, and the two became just one long island. But in 1846, a hurricane created two major inlets. One, now called Oregon Inlet, sliced through the sand, leaving today’s Pea Island to the south and Bodie Island to the north. And a second inlet, now known as Hatteras Inlet, once again separated Hatteras Island from Ocracoke Island. -

An Historical Overviw of the Beaufort Inlet Cape Lookout Area of North

by June 21, 1982 You can stand on Cape Point at Hatteras on a stormy day and watch two oceans come together in an awesome display of savage fury; for there at the Point the northbound Gulf Stream and the cold currents coming down from the Arctic run head- on into each other, tossing their spumy spray a hundred feet or better into the air and dropping sand and shells and sea life at the point of impact. Thus is formed the dreaded Diamond Shoals, its fang-like shifting sand bars pushing seaward to snare the unwary mariner. Seafaring men call it the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Actually, the Graveyard extends along the whole of the North Carolina coast, northward past Chicamacomico, Bodie Island, and Nags Head to Currituck Beach, and southward in gently curving arcs to the points of Cape Lookout and Cape Fear. The bareribbed skeletons of countless ships are buried there; some covered only by water, with a lone spar or funnel or rusting winch showing above the surface; others burrowed deep in the sands, their final resting place known only to the men who went down with them. From the days of the earliest New World explorations, mariners have known the Graveyard of the Atlantic, have held it in understandable awe, yet have persisted in risking their vessels and their lives in its treacherous waters. Actually, they had no choice in the matter, for a combination of currents, winds, geography, and economics have conspired to force many of them to sail along the North Carolina coast if they wanted to sail at all!¹ Thus begins David Stick’s Graveyard of the Atlantic (1952), a thoroughly researched, comprehensive, and finely-crafted history of shipwrecks along the entire coast of North Carolina. -

Cape Fear Sail & Power Squadron

Cape Fear Sail & Power Squadron We are America’s Boating Club® NORTH CAROLINA OCEAN INLETS Listed in order of location north to south Oregon Inlet Outer Banks. Northern-most ocean inlet in NC. Located at the north end of New Topsail Inlet Near ICW Mile 270. As of July Hatteras Island. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. 7, ’20, the inlet was routinely passable by medium Federally maintained.* See Corps of Engineers and small vessels at higher states of the tide. survey1 However, buoys were removed in 2017 due to shoaling, so the channel is currently unmarked. See Hatteras Inlet Outer Banks. Located between Corps of Engineers survey Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. Once inside the inlet itself, the Little Topsail Inlet Located ½ N.M. SW of New passage of a lengthy inshore channel is required to Topsail Inlet. Not normally passable and does not access the harbor or navigable portions of Pamlico currently connect to navigable channels inshore. Sound. Rich Inlet Located between Topsail and Figure 8 Ocracoke Inlet Outer Banks. Located at S end Islands near ICW Mile 275. of Ocracoke Is. Provides access to Pamlico Sound. Once inside the inlet itself, the passage of a shifting Mason Inlet Located between Figure 8 Island and inshore channel named Teaches Hole is required to Wrightsville Beach island near ICW Mile 280. access the harbor or navigable portions of Pamlico Dredged in 2019 but not buoyed as of July 31, ’20. Sound. Buoyed & lighted as of June 29, ’19. See Corps of Engineers surveys1 (for the inlet) and (for Masonboro Inlet Located between Wrightsville Teaches Hole).