1980 Andrew J. Whitford Submitted in Parti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

,V V4 ,V V4 I tf TIlE ZIMBfBWE REVIEW TO OUR READERS: We extend our thanks to the hundreds of readers of "THE ZIMBABWE REVIEW" who have expressed their appreciation of the material that was ventilated in the columns of our previous issues. We hope to be able to continue providing revealing information on the Rhodesian situation. CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL 2 INTERVIEW WITH PRESIDENT OF ZAPU J. M. NKOMO 3 NKOMO'S ZIMBABWE DAY SPEECH IN LUSAKA' 4 SPEECH BY COMRADE JOSHUA NKOMO 7 ANGOLA: FACTS AND PERSPECTIVES 10 SANCTION VIOLATION:HOWOILREACHEDRHODESIA 12 PATRIOTIC FRONT PRESS STATEMENT 13 INSIDE ZIMBABWE: REVOLUTIONARY ACTIVITIES OF ZPRA (ZIPA) 14 THIRD FRELIMO CONGRESS 16 PAN-AFRICAN TRADE UNION CONFERENCE OF SOLIDARITY WITH THE WORKERS AND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN AFRICA 18 STATEMENT ON "THE GREAT OCTOBER SOCIAL1ST REVOLUTION '- AND THE LIBERATION MOVEMENTS" 21 The Zimbabwe Review is produced and published by the Information and Publicity Bureau of the Zimbabwe African People's Union. All inquiries should be directed to: The Chief Editor of The Zimbabwe Review P.O. Box 1657 Lusaka Zambia. EDITORIAL The British Government. has again sent one of its political personalities on a whirlwind tour of Tanzania, Mozambique, South Afrca, Botswana, Zambia, Rhodesia and, though belatedly included, Angola, to discuss the Rhodesian issue. This time the personality is the Commonwealth and Foreign Relations Secretary, Dr. David Owen. Dr. Owen came hard on the heels of Mr. Ivor Richard whose disappointment with the Rhodesian fascist regime has very widely publicised by the British news media. Mr. Richard visited Rhodesia after several attempts had been made to reach a settlement with Smith and his fascist league. -

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

Zimbabwe . Bulletin

25c ZIMBABWE .BULLETIN april 77 Newsletter of the ZANU Support Committee New York UPDATE 1977 has ushered in new complexities in the struggle for Zimbabwean national liberation. The collapse of the WHAT SOUTH AFRICA IS UP TO Geneva negotiations has stepped up the struggles of all South African Prime Minister Vorster continues to favor forces involved. The conference adjourned on Dec. 15, and a negotiated settlement, knowing full well the,threat that was scheduled to reconvene on Jan. 17. Ivor Richard armed struggle for true national liberation in Zimbabwe Britain's man-in-charge at yeneva, subsequently under: , poses to his own regime. He also hopes that his role in took his own shuttle diplomacy in Southern Africa to put dealing with Smith will gain South Africa more credibility on the international scene and with African neo-colonial fo~ard Britain's plan to replace the Kissinger proposals which had been rejected by the nationalist forces. The countries. There is trouble on the home front however Richard Plan proposed a transitional government with rising unemployment, decreasing foreign investment and increasing black resistance, which has mobilized the co~p.osed of an In~rim Commission, appointed by BritaIn, and a Council of Ministers composed of five more intransigent white forces against abandoning Smith. members from each of the forces at Geneva (ZANU* Therefore, he has given public assurances that he will not ZAPU* ANC*Sithole, the Rhodesia Front and other white force Smith beyond the bounds of the Kissinger Plan. forces). This plan was considered acceptable by the U.S., Also, Vorster told Ivor Richard that South Africa would not South Africa, and the liberation forces as a basis to return tolerate any guerrilla action in Zimbabwe that would in to Geneva. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

The Foreign Service Journal, July 1975

FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL JULY 1975 60 CENTS isn I The diplomatic | way to save. ■ All of these outstanding Ford-built cars are available to you at special diplomatic discount savings. ■ Delivery will be arranged for you either stateside or ■ overseas. And you can have the car built to Export* or Domestic specifications. So place your order now for diplomatic savings on the cars for diplomats. For more information, contact a Ford Diplomatic Sales Office. Please send me full information on using my diplomatic discount to purchase a new WRITE TO: DIPLOMATIC SALES: FORD MOTOR COMPANY 815 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006/Tel: (202) 785-6047 NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE/COUNTRY ZIP Cannot be driven in the U.S American Foreign Service Association Officers and Members of the Governing Board THOMAS D. BOY ATT, President F. ALLEN HARRIS, Vice President JOHN PATTERSON, Second Vice President RAYMOND F. SMITH, Secretary JULIET C. ANTUNES, Treasurer CHARLOTTE CROMER & ROY A. HARRELL, JR., AID Representatives FRANCINE BOWMAN, RICHARD B. FINN, CHARLES O. HOFFMAN & FRANCIS J. McNEIL, III State Representatives STANLEY A. ZUCKERMAN, USIA Representative FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL JAMES W. RIDDLEBERGER & WILLIAM 0. BOSWELL, Retired Representatives JULY 1975: Volume 52, No. 7 Journal Editorial Board RALPH STUART SMITH, Chairman G. RICHARD MONSEN, Vice Chairman FREDERICK QUINN JOEL M. WOLDMAN EDWARD M. COHEN .JAMES F. O'CONNOR SANDRA L. VOGELGESANG Staff RICHARD L. WILLIAMSON, Executive Director DONALD L. FIELD, JR.. Counselor HELEN VOGEL, Committee Coordinator CECIL B. SANNER, Membership and Circulation Communication re: Excess Baggage 4 Foreign Service Educational AUDINE STIER and Counseling Center MARY JANE BROWN & Petrolimericks 7 CLARKE SLADE, Counselors BASIL WENTWORTH Foreign Policy Making in a New Era: Journal SHIRLEY R. -

The Other Side of Campus Indiana University’S Student Right and the Rise of National Conservatism

The Other Side of Campus Indiana University’s Student Right and the Rise of National Conservatism JASON S. LANTZER n a brisk spring day in March 1965, an estimated 300 Indiana 0University students assembled in Dunn Meadow, the green oasis beside the Indiana Memorial Union where students often relaxed between classes or met to play games. This day was different, however, as these students gathered not to enjoy the atmosphere, but to speak their minds about the war in Vietnam. They carried signs, chanted slogans, and generally behaved, according to the campus newspaper, the Indiana Daily Student (IDS), in a manner not unlike that of an additional 650 students and locals who had also assembled in the meadow to hear speeches about the civil rights move- ment in the wake of the recent march on Selma, Alabama.‘ This convergence of civil rights and Vietnam demonstrations may sound like a typical episode of 1960s campus activism, but it was not. A good half of the students attending the Vietnam rally marched in support of the United States’ commitment to halting the advance of communism in Southeast Asia. While such a show of support was hardly uncommon, either at IU or at other college campuses nationwide, subsequent studies of 1960s Jason S. Lantzer is a visiting lecturer in history at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. For reading of and assistance with this essay, he extends his thanks to Prof. Nick Cullather, Chad Parker, and the IMH staff. ‘Indiana Daily Student, March 10, 11, 12, 13, 1965; hereafter cited as IDS INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY, 101 (June 2005) 0 2005, Trustees of Indiana University. -

Eurasia Foundation Network

Engaging Citizens Empowering Communities Eurasia2009 Network Foundation Yearbook Engaging Citizens, Empowering Communities Eurasia Foundation Network EURASIA FOUNDATION OF CENTRAL ASIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Advisory Council, Board of Trustees.....................1 2009 Letter from the Chair and President..............................2 The Eurasia Foundation Network......................................3 Yearbook Overview.....................................4 New Eurasia Foundation.................................5 Eurasia Foundation of Central Asia..........................6 Eurasia Partnership Foundation.................................7 East Europe Foundation.................................8 Youth Engagement...................9 Local Economic Development...........................11 Public Policy and The Eurasia Foundation Network comprises New Eurasia Foundation (Russia), Eurasia Foundation of Central Asia, Eurasia Partnership InstitutionFoundation Building.................13 (Caucasus), East Europe Foundation (Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova) and Eurasia Foundation (United States). Since 1993, Eurasia Foundation and the network have invested more than $360 million in local and cross-border projects to promote civic and economic inclusion throughout the Eurasia region.Independent Media.................15 For more information about the Eurasia Foundation Network, please visit http://www.eurasia.org/ Cross-Border Programs ........17 Eurasia Foundation Financials..................................19 EAST EUROPE EURASIA FOUNDATION EFFOUNDATION Network -

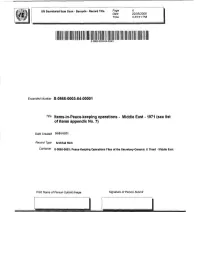

Middle East -1971 (See List of Items Appendix No. 7)

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 4 Date 22/05/2006 Time 4:43:51 PM S-0865-0003-04-00001 Expanded Number S-0865-0003-04-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - Middle East -1971 (see list of items appendix No. 7) Date Created 01/01/1971 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0865-0003: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant - Middle East Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit x/, 7 Selected Confidential Reports on OA-6-1 - Middle East 1971 Cable for SG from Goda Meir - 1 January 1971 2 Notes on meeting - 4 January 1971 - Present: SG, Sec. of State Rogers, 0 Ambassador Charles Yost, Mr. Joseph Sisco, Mr. McClosky and Mr. Urquhart t 3) Middle East Discussions - 5 January 1971 - Present: Ambassador Tekoah Mr. Aphek, Ambassador Jarring, Mr. Berendsen 4 Letter from Gunnar Jarrint to Abba Eban - 6 January 1971 x i Letter to Gunnar Jarring from C.T. Crowe (UK) 6 January 1971 *6 Notes on meeting - 7 January 1971 - Present: SG, Sir Colin Crowe 7 Notes on meeting - 7 January 1971 - Present: SG, Mr. Yosef Tekoah 8 "Essentials of Peace"(Israel and the UAR) - 9 January 1971 9 "Essentials of Peace" (Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordon - 9 January 1971 Statement by El Tayalt - 13 January 1971 Minutes of meeting - 13 January 1971 - Present: M. Masmoudi, El-Goulli, Mr. Fourati, Mr. Jarring, Mr. Berendsen^ Letter from William P. Rogers - 15 January 1971 Letter - Middle East - 15 January 1971 Implementation of Security Council Resolution 242 of 22 November 1967 For The Establishment of a Just and Lasting Peace in the Middle East - 18 January 1971 C H-^-^ ?-«-r-"~) Comparison of the papers of Israel and the United Arab Republic 18 January 1971 L " Notes on meeting - 19 January 1971 - Present: SG, Ambassador Yost, USSR - 1 January 1971 - Middle East Communication from the Government of Israel to the United Arab Republic through Ambassador Jarring - 27 January 1971 France - 27 January 1971 - Middle East Statement by Malik Y.A. -

9/11/80; Container 176 to Se

9/11/80 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/11/80; Container 176 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf ,. ' ' THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 9/11/80 Jim Laney President Carter asked me to send you the enclosed copy of your letter with his remarks along with his best wishes. :J�¥J:;�]·f�JP�t��:�����'1 -� sJ Su Clough THE WHITE HOUSE I1r. Jim La:nP.v Lullwater House 1463 Clifton Road, N.E. Atlanta,_ Georgia 30329 .. -�···- ., ' I -_,.. / ·,!., ' ·' · "· · ... _.;_ . j '. �� ..... _ ' �- . .. · .. ----·----·" --- �--------��------�----------------------------------------------------------------�--------------�� i . ·.-· .�..... ·._ · ..... · . :.· . ..... ._ ... � .. _.- '· ·.· .. ""' -�: . .... .--·_,.._, -� ·, ' ·'( �\: ' �'Vi ,. "· !Q .� .. 0 rt�. , . , ., r� . ' . ; D��� �j. ·. 1.·, r; ·'· �·t�.f. lj•!• ·� . ,. :'$ :! . �:·:- '4J,o '', �-. • ·- '\�., ' ·1 (/ . ,.,_ /· b THE WHITE HOUSE ., WASHINGTON ' ) · ;1 ' ' l. ',7,._ ,, '}i' -�·�� ... 9/11/80 / <:1 '·f' ,:;!,\. .'r �... · Note for Files l: , . , ,, . ' /,, '· ' ,. J:-' ,1 Attached is from '•. " 0 ,,. ' T. .i I President James Laney •. · � p ' ·, (President of Emory University ·,, 0 in Atlanta, Geor�ia) ·,, • ·'"! c'• ..�- : rt·�. ( ":� J � , , ' ' �:, it is most likely that the letter was sent by Laney either to Bob Maddox who then '• delivered it to the First Lady --� who gave it to the President... ·· 1 or sent by Laney to Bob Maddox • v s ·. who had .it sent/given to the President by some other person who gave it directly to the '' �). President. --sse ' l .. ' )'r·. ·'' 0 i; ·�2.; :1_,··f, . , ij 't��·) 0 �; '' .. ···---·-··· ··�- -�-·----.,......... _,______ , ___ ·-... � ____ ..._____ ,.-........ ...... ··-"· y Msde �lectro§tatlc Cop on pu;rpo�e.C� for Preseqvs�S September 4, 1980 Memorandum to: President Jimmy Carter From: James T. -

The Role of HM Embassy in Washington

The Role of HM Embassy in Washington edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Role of HM Embassy in Washington ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 83 8 The Role of HM Embassy in Washington Held 18 June 1997 in the Map Room, Foreign & Commonwealth Office Chaired by Lord Wright of Richmond Seminar edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah Institute of Contemporary British History Contents Contributors 9 Citation Guidance 11 The Role of HM Embassy in Washington 13 edited by Gillian Staerck and Michael D. Kandiah Contributors Editors: GILLIAN STAERCK Institute of Contemporary British History DR MICHAEL KANDIAH Institute of Contemporary British History Chair: LORD WRIGHT OF Private Secretary to Ambassador and later First Secretary, Brit- RICHMOND ish Embassy, Washington 1960-65, and Permanent Under-Sec- retary and Head of Diplomatic Service, FCO 1986-91. Paper-giver DR MICHAEL F HOPKINS Liverpool Hope University College. Witnesses: SIR ANTONY ACLAND GCMG, GCVO. British Ambassador, Washington 1986-91. PROFESSOR KATHLEEN University College, University of London.