FINAL Matsusaka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cartographic Steppe: Mapping Environment and Ethnicity in Japan's Imperial Borderlands

The Cartographic Steppe: Mapping Environment and Ethnicity in Japan's Imperial Borderlands The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Christmas, Sakura. 2016. The Cartographic Steppe: Mapping Environment and Ethnicity in Japan's Imperial Borderlands. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840708 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Cartographic Steppe: Mapping Environment and Ethnicity in Japan’s Imperial Borderlands A dissertation presented by Sakura Marcelle Christmas to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2016 © 2016 Sakura Marcelle Christmas All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Ian Jared Miller Sakura Marcelle Christmas The Cartographic Steppe: Mapping Environment and Ethnicity in Japan’s Imperial Borderlands ABSTRACT This dissertation traces one of the origins of the autonomous region system in the People’s Republic of China to the Japanese imperial project by focusing on Inner Mongolia in the 1930s. Here, Japanese technocrats demarcated the borderlands through categories of ethnicity and livelihood. At the center of this endeavor was the perceived problem of nomadic decline: the loss of the region’s deep history of transhumance to Chinese agricultural expansion and capitalist extraction. -

Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China's

C O R P O R A T I O N Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China’s Aerospace Forces Selections from the Inaugural Conference of the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Edmund J. Burke, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Mark R. Cozad, Timothy R. Heath For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF340 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9549-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface On June 22, 2015, the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), in conjunction with Headquarters, Air Force, held a day-long conference in Arlington, Virginia, titled “Assessing Chinese Aerospace Training and Operational Competence.” The purpose of the conference was to share the results of nine months of research and analysis by RAND researchers and to expose their work to critical review by experts and operators knowledgeable about U.S. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Library of Congress Classification

KZ LAW OF NATIONS KZ Law of nations Class here works on legal principles recognized by nations, and rules governing conduct of nations and their relations with one another, including supra-regional Intergovernmental Organizations (IGO's) and the legal regimes governing such organizations Class here the sources of international law, i.e. the law of treaties, arbitral awards and judicial decisions of the international courts For organizations with missions limited to a particular region, see the appropriate K subclass for the regional organization (e. g. KJE for the Council of Europe) For works on comparative and uniform law of two or more countries in different regions, and on private international law (Conflict of laws), see subclass K Bibliography For bibliography of special topics, see the topic 2 Bibliography of bibliography 3 General bibliography 4 Library catalogs. Union lists 5 Bibliography of periodicals, society publications, collections, etc. For indexes to a particular publication, see the publication 5.5 Indexes to periodical articles Periodicals For periodical articles consisting primarily of informative material, e. g. news letters, bulletins, etc. relating to a particular subject, see the subject. For collected papers, proceedings, etc. of a particular congress, see the congress. For particular society publications, e. g. directories, see the society For periodicals consisting predominantly of legal articles, regardless of subject matter and jurisdiction see K1+ 21 Annuals. Yearbooks Class here annual publications and surveys on current international law developments and analysis of recent events, including official document collections e. g. Annuaire français de droit international; Asian Yearbook of International Law; British Yearbook of International Law; Jahrbuch für internationales Recht; Suid-Afrikaanse jaarboek vir volkereg For annual reports on legal activities of intergovernmental organizations, see the organization (e. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

I.D. Jiangnan 241

I.D. THE JIANGNAN REGION, 1645–1659 I.D.1. Archival Documents, Published Included are items concerning Jiangnan logistical support for campaigns in other regions, as well as maritime attacks on Jiangnan. a. MQSL. Ser. 甲, vols. 2–4; ser. 丙, vols. 2, 6-8; ser. 丁, vol. 1; ser. 己, vols. 1–6. b. MQCZ. I: Hongguang shiliao 弘光史料, items 82, 87. III: Hong Chengchou shiliao 洪承疇史料, item 50; Zheng Chenggong shiliao 鄭成 功史料, item 82. c. MQDA. Ser. A, vols. 3–8, 11, 13, 17, 19–26, 28–31, 34–37. d. QNMD. Vol. 2 (see I.B.1.d.). e. QNZS. Bk. 1, vol. 2. f. Hong Chengchou zhangzou wence huiji 洪承疇章奏文冊彙輯. Comp. Wu Shigong 吳世拱. Guoli Beijing daxue yanjiuyuan wenshi congkan 國立北 京大學研究院文史叢刊, no. 4. Shanghai: CP, 1937. Rpts. in MQ, pt. 3, vol. 10. Rep. in 2 vol., TW, no. 261; rpt. TWSL, pt. 4, vol. 61. Hong Chengchou was the Ming Viceroy of Jifu and Liaoning 薊遼 總 督 from 1639 until his capture by the forces of Hungtaiji in the fall of Songshan 松山 in 1642. After the rebel occupation of Beijing and the death of the CZ emperor, Hong assumed official appointment under the Qing and went on to become the most important former Ming official to assist in the Qing conquest of all of China (see Li Guangtao 1948a; Wang Chen-main 1999; Li Xinda 1992). Many of his very numerous surviving memorials have been published in MQSL and MQDA. In the present col- lection of 67 memorials, 13 represent his service as Viceroy of Jiangnan and “Pacifier of the South” 招撫南方 from 1645 through 1648. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

The Eclipse of 21 June 1629 in Beijing in the Context of the Reform of the Chinese Calendar

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 23(2), 327‒334 (2020). THE ECLIPSE OF 21 JUNE 1629 IN BEIJING IN THE CONTEXT OF THE REFORM OF THE CHINESE CALENDAR Sperello di Serego Alighieri INAF ‒ Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] and Elisabetta Corsi Sapienza Università di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Roma, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper examines the predictions made by Chinese, Muslim and Jesuit astronomers of the eclipse of 21 June 1629 in Beijing, allegedly the event that determined Emperor Chongzhen‘s resolution to reform the calendar using the Western method. In order to establish the accuracy of these predictions, as reported at the time by the Chinese scholar and convert Xu Guangqi, we have compared them with an accurate reconstruction of the eclipse made at NASA. In contrast with current opinions, we argue that the prediction made by the Jesuits was indeed the most accurate. It was in fact instrumental in dissipating Chongzhen‘s doubts about the need to entrust Jesuit missionaries serving at the Chinese court with the task of reforming the calendar, leading to the first important scientific collaboration between Europe and China. Keywords: Eclipses, Chinese calendar reform, Jesuit savants. 1 INTRODUCTION to the Empire, and making astronomical pre- dictions and calculations, may not be fully ap- Eclipses are inauspicious events in Chinese preciated unless attention is paid to the quality traditional worldview, bearers of major disast- of the Jesuit scientific and technical expertise, ers. For centuries astronomers serving at the a condition that enabled them to retain a lead- Chinese Court—from the Tang Dynasty on, ing position in the Astronomical Bureau for a there were also foreign astronomers, firstly century and a half, starting with Adam Schall Brahmans then Arabs and lately Europeans— von Bell‘s appointment in 1644, at the estab- strove to make the best eclipse forecasts, lest lishment of the Qing Dynasty. -

China's Provincial Leaders Await Promotion

Li, China Leadership Monitor, No.1 After Hu, Who?--China’s Provincial Leaders Await Promotion Cheng Li China’s provincial leadership is both a training ground for national leadership and a battleground among various political forces. Provincial chiefs currently carry much more weight than ever before in the history of the PRC. This is largely because the criteria for national leadership have shifted from revolutionary credentials such as participation in the Long March to administrative skills such as coalition-building. In addition, provincial governments now have more autonomy in advancing their own regional interests. Nonetheless, nepotism and considerations of factional politics are still evident in the recruitment of provincial leaders. Emerging top-level national leaders--including Hu Jintao, Zeng Qinghong, and Wen Jiabao--have all drawn on the pool of provincial leaders in building their factions, hoping to occupy more seats on the upcoming Sixteenth Central Committee and the Politburo. At the same time, new institutional mechanisms have been adopted to curtail various forms of nepotism. The unfolding of these contradictory trends will not only determine who will rule China after 2002, but even more importantly, how this most populous country in the world will be governed. During his recent visit to an elementary school in New Mexico, President George W. Bush offered advice to a child who hoped to become president. “If you want to be President, I would suggest you become a governor first,” said President Bush, “because governors make decisions, and that’s what presidents do.”1 What is true of the career path of American leaders seems also to be true of their counterparts in present-day China. -

Temporal and Spatial Variations of Mesozoic Magmatism and Deformation in the North China Craton: Implications for Lithospheric Thinning and Decratonization

Earth-Science Reviews 131 (2014) 49–87 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Temporal and spatial variations of Mesozoic magmatism and deformation in the North China Craton: Implications for lithospheric thinning and decratonization Shuan-Hong Zhang a,⁎,YueZhaoa, Gregory A. Davis b,HaoYea,FeiWua a Institute of Geomechanics, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, MLR Key Laboratory of Paleomagnetism and Tectonic Reconstruction, Beijing 100081, China b Department of Earth Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0740, USA article info abstract Article history: Mesozoic (Triassic–Cretaceous) magmatic rocks and structural deformation are widely distributed in the North Received 16 August 2013 China Craton (NCC) and are crucial to understanding the timing, location, and geodynamic mechanisms of Accepted 16 December 2013 lithospheric thinning and decratonization of the NCC. Our new geochronological, geochemical and structural Available online 30 December 2013 data combined with previously published results on Mesozoic magmatic rocks and deformational structures in the NCC indicate a temporal and spatial migration of magmatism and deformation from its margins to its cratonal Keywords: interior. Triassic and Early Jurassic igneous rocks are only distributed along the northern, southern and eastern Magmatism Deformation margins of the NCC. In contrast, Cretaceous magmatic rocks are widely distributed in whole eastern and central Mesozoic parts of the NCC. There is a younging trend for Mesozoic magmatic rocks from the northern and eastern parts Decratonization (Yanshan, Jiaodong Peninsula and Liaodong) to the central part of the NCC (Taihangshan). Mesozoic deformation Lithospheric thinning in the NCC exhibits a similar migration trend from craton margins to its inland areas. -

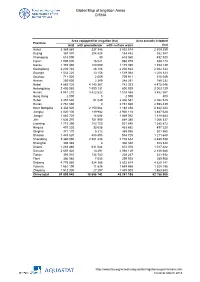

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52