(POST)COLONIAL in QUEER by Robert Larue DISSERTATION Subm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Landmarks That Were Part of the Underground Gay Scene in the 1980S

Mumbai landmarks that were part of the underground gay scene in the 1980s By Vikram Phukan |Posted 26-Nov-2014 The Boatman, a book by former aid worker John Burbidge, is set in India during the early 1980s, unearthing facets and talking about Mumbai landmarks which were part of a thriving but subterranean gay scene Foraging around the internet for the phrase ‘Bombay Bandstand’ yields an odd million or two hits for the star-strewn promenade at Bandra, a heady sea-sprayed stretch of concrete that has been in existence for less than a decade. TO BE FREE: Like these pigeons at the Gateway, silent sentinel to the subterranean gay culture in the city in the '80s and '90s. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar Bandstand culture in Mumbai, now seemingly obscured on the internet, actually goes back a whole century or more. References to it can be found in vintage texts and jazz tomes, although there has been a resurgence of interest in recent times (if ever so slightly), via the good offices of the Bandstand Revival project, which has attempted to bring back elusive traces of a bygone era by springing the pomp of an after-dusk live brass band upon an unsuspecting populace, who have long become completely inured to such instances of embedded culture. However, unknown to many except those with first-hand experience (many of whom were sworn to secrecy by the dictates of those times), the twilight whirring at a bandstand has also been associated with the carousel waltz of an underground culture from as far back as the 70s, with the Cooperage Band Stand Garden and Children’s Traffic Park in Colaba (or simply, Bandstand) once being the crowning glory of a thriving gay scene in the city, and a symbol of her subterranean hedonism. -

And Aravanis/Hijras

UNDERSTANDING MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN (MSM) AND HIJRAS & PROVIDING HIV/STI RISK REDUCTION INFORMATION Basic Training for Clinicians & Counselors in Sexual health/STI/HIV TRAINER’S MANUAL September 2005 Developed by: Dr. Venkatesan Chakrapani, M.D. Supported by: Fund for Leadership Development (FLD) fellowship grant of The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Indian Network for People living with HIV/AIDS (INP+) Correspondence: Dr. Venkatesan Chakrapani, M.D., C/o Indian Network for People Living with HIV/AIDS (INP+) Flat No.6, Kash Towers, 93, South West Boag Road, T. Nagar, Chennai-600017. Phone: 91-44-24329580/81 Fax: 91-44-24329582 Email: [email protected] Website: www.indianGLBThealth.info Trainer’s Manual - MSM & Hijras, Sep 2005 Venkatesan Chakrapani www.indianGLBThealth.info 1 _________________________________________________________________________ Two gay Englishmen once came to Gandhi – - this was in the 1930’s --- and asked him what he thought about their relationship. After questioning them a bit, Gandhi fell silent for a short time, and then said, “The greatest gift that God gives us is another person to love.” Placing the two men’s hands in each other’s, he then quietly asked, ‘Who are we to question God’s choices?” (From ‘Tackling gay issues in schools’. A resource module edited by Leif Mitchell. GLSEN Connecticut. 1999. II edition.) _________________________________________________________________________ Trainer’s Manual - MSM & Hijras, Sep 2005 Venkatesan Chakrapani www.indianGLBThealth.info 2 Reviewers of the Trainer’s Manual: Thanks to the following persons who reviewed this trainer’s manual and provided useful suggestions and comments. - Ashok Row Kavi, The Humsafar Trust, Mumbai - Paige Passano, Population Services International (PSI), Mumbai - L Ramakrishnan, SAATHII, Chennai - Dr. -

Homosexuality and Homphobia In

HOMOSEXUALITY AND HOMOPHOBIA IN INDIAN POPUlAR CULTURE: REFLECTIONS OF THE LAW ? Danish Sheikh Introduction Some men like Jack and some like Jill; I'm glad I like them both; but still I wonder ifthis freewheeling really is an enlight ened thing - or is its greater scope a sign ofdeviance from some party line ?In the strict ranks ofGay and Straight, What is my status? Stray? or Great? Vikram Seth Homosexuality and bisexuality, as we now know from modern research, are ubiquitous throughout the world. Whether tolerated or not, they are practiced in every culture to some degree.! The differences among cultures is the degree of openness regarding practice. In a democratic and pluralistic country like India, it is a shame that we have a law that abuses human rights and limits fundamental freedoms such as is enumerated in Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which, by prohibiting "carnal intercourse against the order of nature"2 in effect punitively criminalizes private, consensual sexual acts between people of the same sex. India is a country with vibrant popular culture. Nowhere is the collective consciousness of the nation probably better essayed than in the cinema, which is viewed with passionate fervour. Taking cinema as the mainstay of Indian popular culture, along with a few examples from literature and television, this paper seeks to understand the link between the depiction. of homosexuality in Indian popular culture and the law, which as it stands now is blatantly homophobiC. Different viewpoints are looked from and observed in Indian popular culture, such as the non - acceptance of homosexuality by some quarters, the crude stereotyping that is played to squeeze out a few laughs, and the slowly emerging new wave of thought that treats the subject with a compassionate eye, and gives it a humane treatment. -

Creating Inclusive Workplaces for LGBT Employees in India

"In a time when India is seeing a lot of positive changes that will shape the future of its LGBTQ citizens, Community Business has come out with a splendid guide which is not only comprehensive, but also deals with issues that are very specific to India in a well researched manner. Today, in 2012, it is very essential for corporates based in India to come out of the illusion that they have no LGBTQ employees on board, and create a positive environment for them to come out in. I definitely suggest every Corporate HR, Talent Acquisition, and D&I team should read the 'Creating Inclusive Workplaces for LGBT Employees in India' resource guide while shaping policies that help create a more inclusive and supportive work environment for all.” Tushar M, Operations Head (India) Equal India Alliance For more information on Equal India Alliance go to: www.equalindiaalliance.org Creating Inclusive “The business case for LGBT inclusion in India is real and gaining momentum. India plays an increasingly vital role in our global economy. Creating safe and equal workplaces is essential for both its LGBT employees and India’s continued Workplaces for economic success. Community Business’ LGBT Resource Guide for India provides an invaluable tool for businesses in India to stay competitive on the global stage – and be leaders for positive change there.” LGBT Employees Selisse Berry, Founding Executive Director Out & Equal Workplace Advocates For more information on Out & Equal Workplace Advocates go to: www.OutandEqual.org in India “Stonewall has been working for gay people’s equality since 1989. Our Diversity Champions programme works with the employers of over ten million people globally improving the working environment for LGB people. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. Abha Dawesar, Babyji (New Delhi: Penguin, 2005), p. 1. 2. There are pitfalls when using terms like “gay,” “lesbian,” or “homosexual” in India, unless they are consonant with “local” identifications. The prob- lem of naming has been central in the “sexuality debates,” as will shortly be delineated. 3. Hoshang Merchant, Forbidden Sex, Forbidden Texts: New India’s Gay Poets (London: Routledge, 2009), p. 62. 4. Fire, dir. by Deepa Mehta (Trial by Fire Films, 1996) [on DVD]. 5. Geeta Patel, “On Fire: Sexuality and Its Incitements,” in Queering India, ed. by Ruth Vanita (London: Routledge, 2002), pp. 222–233; Jacqueline Levitin, “An Introduction to Deepa Mehta,” in Women Filmmakers: Refocusing, ed. by Jacqueline Levitin, Judith Plessis, and Valerie Raoul (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002), pp. 273–283. 6. A Lotus of Another Color, ed. by Rakesh Ratti (Boston: Alyson Publi- cations, 1993); Queering India, ed. by Ruth Vanita; Seminal Sites and Seminal Attitudes—Sexualities, Masculinities and Culture in South Asia, ed. by Sanjay Srivastava (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2004); Because I Have a Voice: Queer Politics in India, ed. by Arvind Narrain and Gautam Bhan (New Delhi: Yoda Press, 2005); Sexualities, ed. by Nivedita Menon (New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2007); The Phobic and the Erotic: The Politics of Sexualities in Contemporary India, ed. by Brinda Bose and Suhabrata Bhattacharyya (King’s Lynn: Seagull Books, 2007). 7. Walter Jost and Wendy Olmsted, “Introduction,” in A Companion to Rhetoric and Rhetorical Criticism, ed. by Walter Jost and Wendy Olmsted (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), pp. xv–xvi (p. xv). 8. Quest/Thaang, dir. -

Gender/Sexual Transnationalism and the Making Of

Globalizing through the Vernacular: Gender/sexual Transnationalism and the Making of Sexual Minorities in Eastern India A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Aniruddha Dutta IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Richa Nagar, Jigna Desai May 2013 © Aniruddha Dutta, 2013. i Acknowledgements The fieldwork that underlies this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and guidance of my kothi, dhurani and hijra friends and sisters who have so generously invited me into their lives and worlds. Furthermore, numerous community activists, leaders and staff members working in community-based and non-governmental organizations shared their time and insights and included me into their conversations and debates, for which I am deeply grateful. I would especially like to thank the communities, activists and staff associated with Madhya Banglar Sangram, Dum Dum Swikriti Society, Nadia Sampriti Society, Koshish, Kolkata Rista, Gokhale Road Bandhan, Kolkata Rainbow Pride Festival (KRPF), Sappho for Equality, Pratyay Gender Trust, PLUS, Amitié Trust, Solidarity and Action Against the HIV Infection in India (SAATHII), Dinajpur Natun Alo Society, Nabadiganta, Moitrisanjog Society Coochbehar, and Gour Banglar Sanhati Samiti. The detailed review and inputs by my advisers and committee members have been invaluable and have helped shape and improve the dissertation in more ways than I could enlist. I am particularly grateful to my co-advisers, Prof. Richa Nagar and Prof. Jigna Desai for their consistent and meticulous mentorship, guidance, advice and editorial inputs, which have shaped the manuscript in innumerable ways, and without which this dissertation could not have been completed on schedule. -

Alternative Sexuality Versus Male Homophobia in R

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 7 ~ Issue 7 (2019)pp.:17-20 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Interrogating cityscape: Alternative sexuality versus Male homophobia in R. Raj Rao’s The Boyfriend Anupom Kumar Hazarika PhD Research Scholar, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Guwahati ABSTRACT: Henri Lefebvre is of the opinion that every society produces its own space. Sex and sexuality cannot be decoupled from space. Yi-Fu Tuan associates city with freedom and openness. R. Raj Rao's cult novel The Boyfriend has Bombay as its backdrop. The first section of my paper will give a brief overview of the setting of the text. The second section will take recourse to the theorists mentioned above to examine how Bombay produces queer spaces. Lastly, I will read select passages within a queer theoretical framework to understand the entanglement between the queer body and society. KEYWORDS: Bombay, space, gay men, heteronormativity Received 07 July 2019; Accepted 25 July, 2019 © the Author(S) 2019. Published With Open Access At www.Questjournals.Org I. INTRODUCTION Setting refers to the where and when of a story. The characters of any novel need a context to exist, and we cannot imagine a story without it. Bombay is the setting of many fictional works. To quote Pinto & Fernandes: “Everyone has a Bombay story, a Bombay they want represented. And everyone‟s Bombay is not the Bombay we thought we knew” (Pinto and Fernandes xii). Salman Rushdie who spent most of his childhood in Bombay depicts Bombay in Midnight’s Children, The Satanic Verses, The Moor’s Last Sigh, and The Ground Beneath Her Feet. -

Frequently Asked Questions 11-17 10 Section 8: Appendix 18

Media Reference Manual Table of Contents Sr. Content Page Number No. 1 Declaration 3 2 Acknowledgement 4 3 Section 1: Why is media important 5 4 Section 2: Observation on media trends 6 5 Section 3: Process 7 6 Section 4: What is our responsibility 8 7 Section 5: How to appear in the Media 9 8 Section 6: Logistics 10 9 Section 7: Frequently Asked Questions 11-17 10 Section 8: Appendix 18 Media Reference Manual 3rd Floor, Manthan Plaza, Near Vakola Masjid, Nehru Road, Vakola, Santacruz (East), Mumbai-400 055 www.humsafar.org Declaration The Humsafar Trust had organized one-day community consultation on LGBT representation in Media. This media manual makes no claim that it is inclusive of the entire LGBTQH community but only a representation of the community. The Humsafar Trust protects the copyrights of this document for and on behalf of all individuals and organizations that made it possible. Reproduction of this document in part or whole can be done only with prior permission of The Humsafar Trust. Note: The document is for free distribution and cannot be used for any commercial purposes. Media Reference Manual Acknowledgements This manual was developed as a part of Humsafar Trust Action plan 2016 for bolstering Supreme Court petition on section 377 towards effective representation of LGBT community in media. We would like to thank The Humsafar Trust for providing us an opportunity to develop this media manual and giving us a necessary guidance. We would like to express gratitude to our inspiration Mr. Ashok Row Kavi (Chairman, The Humsafar Trust) and Mr. -

PORTRAYAL of SEXUAL MINORITIES in HINDI FILMS By

Articles Global Media Journal – Indian Edition/ISSN 2249-5835 Sponsored by the University of Calcutta/ www.caluniv.ac.in Summer Issue / June 2012 Vol. 3/No.1 PORTRAYAL OF SEXUAL MINORITIES IN HINDI FILMS Sanjeev Kumar Sabharwal Assistant Professor Amity School of Communication Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow Campus, Uttar Pradesh, India Website: http://www.amity.edu/lucknow Email:[email protected] and Reetika Sen Academic Coordinator Amity School of Communication Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow Campus, Uttar Pradesh, India Website: http://www.amity.edu/lucknow Email: [email protected] Abstract: Sexual minority or Alternative sexuality comprises of all those people who fall under the categories of Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, Eunuchs. This paper basically compares the portrayal of sexual minorities in Mainstream and Alternative Hindi Cinema. It talks about how Mainstream Hindi cinema which is the most widely distributed cinema in India and abroad has traditionally adopted an attitude of denial or mockery towards LGBTQ community. Representations of sexual Minorities have veered between the sarcasm, comic and the criminal. Where as Alternative Cinema which is confined to film festivals and a handful selected group of viewers portrays sexual minorities in more realistic manner and is successful in raising, expressing & suggesting possible solutions to their problems in more effective manner as compared to the main stream cinema. This is a qualitative as well as quantitative research and the methodology adopted to find out the answers to the questions is content analysis of four Hindi films and survey. Two films of mainstream and two of alternative cinema were selected randomly. Both secondary and primary data was collected, from various reliable sources like journals, websites, articles, movie reviews of different newspapers etc. -

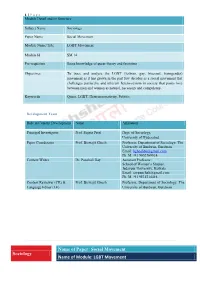

Sociology Name of Paper: Social Movement Name of Module: LGBT Movement

1 | P a g e Module Detail and its Structure Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Social Movement Module Name/Title LGBT Movement Module Id SM 14 Pre-requisites Some knowledge of queer theory and feminism Objectives To trace and analyse the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) movement as it has grown in the past few decades as a social movement that challenges patriarchy and inherent hetero-sexism in society that posits love between men and women as natural, necessary and compulsory. Keywords Queer, LGBT, Heteronormativity, Politics Development Team Role in Content Development Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sujata Patel Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Prof. Biswajit Ghosh Professor, Department of Sociology, The University of Burdwan, Burdwan Email: [email protected] Ph. M +91 9002769014 Content Writer Dr. Panchali Ray Assistant Professor, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata Email: [email protected] Ph. M +91 9831214418 Content Reviewer (CR) & Prof. Biswajit Ghosh Professor, Department of Sociology, The Language Editor (LE) University of Burdwan, Burdwan. Name of Paper: Social Movement Sociology Name of Module: LGBT Movement 2 | P a g e Contents 1. Objective...................................................................................................................................3 2. Introduction...............................................................................................................................3 3. Learning Outcome……………………………………………………………………………..3 -

IND39761 – Gay – New Delhi – Hijras – Bangalore 20 January 2012

Country Advice India India – IND39761 – Gay – New Delhi – Hijras – Bangalore 20 January 2012 1. Please provide an update on relocating to New Delhi, and the general acceptance of gay men there. Three recent pieces of Country Advice provide information on attitudes to homosexuality in New Delhi and other major urban centres of India: RRT Country Advice IND39685, of 12 January 2012, provides a substantial overview of attitudes to homosexuality in India, and information on relocation for gay men.1 Questions 4 and 5 of RRT Country Advice IND39663, of 16 December 2011, address the issue of the acceptance of gay men in Delhi.2 Question 4 of RRT Country Advice IND37162, of 24 August 2010, addresses the issue of the public acceptance of homosexuality in New Delhi and other large urban centres in India.3 The sources quoted in these pieces of Advice suggest that the situation for homosexuals in India is slowly improving, particularly in the big cities, but that broader societal acceptance of homosexuality is some way off. Homosexuals in India continue to be subject to various forms of mistreatment, including harassment, violence and issues with accessing employment. RRT Country Advice IND39685, of 12 January 2012, addresses the issue of relocation for homosexuals in India.4 While this advice located no specific reports on relocation for homosexuals, information was located indicating that there is greater acceptance of homosexuals in urban areas of India as opposed to rural areas, although while homosexuality is increasingly accepted in India‟s urban centres it is still significantly stigmatised. The advice also located sources which indicate that the mistreatment of homosexuals still occurs in urban areas of India. -

Asking the Straight Question: How to Come to Speech in Spite of Conceptual Liquidation As a Homosexual

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2006 Asking the Straight Question: How to Come to Speech in Spite of Conceptual Liquidation as a Homosexual Jose M. Gabilondo Florida International University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Biography Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jose M. Gabilondo, Asking the Straight Question: How to Come to Speech in Spite of Conceptual Liquidation as a Homosexual , 21 Wis Women’s L. J. 1 (2006). Available at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications/88 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 21 Wis. Women's L.J. 1 2006 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Fri Nov 14 19:01:39 2014 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1052-3421 Wisconsin Women's Law Journal VOL. 21 2006 ARTICLES ASKING THE STRAIGHT QUESTION: HOW TO COME TO SPEECH IN SPITE OF CONCEPTUAL LIQUIDATION AS A HOMOSEXUAL Josg Gabilondo* Fo REw O RD ....................................................