Forensic Epidemiology Course Manager’S Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalog of Federally Sponsored Counter-IED Training and Education Resources for State, Local, Tribal, & Territorial Partners

Catalog of Federally Sponsored Counter-IED Training and Education Resources for State, Local, Tribal, & Territorial Partners National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) Office of Infrastructure Protection (IP) Office for Bombing Prevention (OBP) October 2015 Homeland Security This product was developed in coordination with the Joint Program Office for Countering Improvised Explosive Devices (JPO C-IEDs). Introduction The Catalog of Federally Sponsored Counter-IED Training and Education Resources for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) Partners list explosives and IED-related Federal resources of value to SLTT partners. The Catalog was developed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office for Bombing Prevention (OBP) in collaboration with Federal interagency partners through the Joint Program Office for Countering Improvised Explosive Devices (JPO C-IED). The JPO C-IED is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the recently updated U.S. Policy for Countering IEDs. The resources in this Catalog support goals and capabilities outlined in the revised policy and are intended to enhance the effectiveness of U.S. counter-IED efforts, including: • Enhancing the ability to deter, detect, and prevent IEDs before threats become imminent. • Ensuring that protection and response efforts effectively neutralize or mitigate the consequences of attacks that do occur. • Leveraging and integrating a “whole-of-government” approach across law enforcement, diplomatic, homeland security, and military disciplines. • Promoting and enhancing information sharing and cooperation between all levels of the Federal government and SLTT partners. The Catalog identifies training and education resources that are provided directly by the Federal Government or are federally sponsored but delivered by a partner organization, such as the National Domestic Preparedness Consortium. -

4030 ELITE Bomb Disposal Suit & Helmet System

4030 ELITE Bomb Disposal Suit & Helmet System Mission Critical Protection for EOD Operators npaerospace.com 4030 ELITE Core Benefits Mission Critical EOD Protection ADVANCED OPTICAL PERFORMANCE Advanced ergonomic helmet design offers high protection The 4030 ELITE is the next generation Bomb Disposal Suit and Helmet and a wide field of view, with an active demisting visor System from NP Aerospace, a global leader in ballistic protection and Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) design and manufacturing. The high performance, user configurable suit offers 360° protection from the four main EMERGENCY REMOVAL & EXTRACTION aspects of an explosion: fragmentation, overpressure, blast wind and heat radiation. Patented two pull quick release system in jacket and trousers Developed in response to customer feedback and using the latest technology, it is certified enables removal in less than 30 seconds and a new drag to the NIJ 0117.01 Public Safety Bomb Suit Standard by the Safety Equipment Institute. rescue feature allows for rapid emergency extraction The 4030 ELITE delivers improved survivability and ergonomics and accelerated donning and doffing. Protection is enhanced across critical areas such as the neck and torso providing an optimum performance to weight ratio. OPTIMUM SURVIVABILITY AT A LOW WEIGHT High protection across critical areas such as The highly adaptable suit allows for optional customisation with mix and match jacket the torso and neck ensures blast forces are and trouser sizing options and interoperability with the latest user communications deflected and fragments are absorbed and electronics, eliminating the need for a full scale technology upgrade. The 4030 ELITE is the latest addition to the NP Aerospace Bomb Disposal Suit portfolio which is proven and trusted by thousands of EOD operators worldwide. -

Medical Negligence

Page 1 of 11 Review Applied forensic epidemiology, part 1: medical negligence 1 2 2 Methods Development MD Freeman *, PJ Cahn , FA Franklin Abstract Conclusion demiology, is generally described as Introduction Causation in cases of alleged medi- concerning the intersection of epide- The evaluation of the causal relation- cal malpractice is commonly disput- ship between an alleged act of medical provides a systematic approach to the negligence and an adverse health out- causation is not a viable alternative miology and law. More specifically, FE come is an essential element of a med- (i.e.ed. Inthe cases diagnosis in which can directhave multiple specific causation in civil and criminal mat- ical malpractice legal action. In such causes), the indirect evaluation of tersinvestigation3–5. In a clinical of general setting, and the specific evalu- an action, the question of causation is ation of causation is invariably per- also known as the “but-for” question; described in this article provides a formed by clinicians (e.g. a patient’s i.e. but for the negligent act, would the reliablespecific methodologiccausation via framework the methods for ischaemic stroke was caused by his plaintiff still have suffered the adverse uncontrolled high blood pressure), outcome at the same point in time? of causation suitable for presenta- and as such it is rare that a causal de- Forensic epidemiology provides a sys- tionthe quantificationin a court of law. of the probability termination is ever revisited or chal- tematic approach to the investigation lenged. In the legal setting, however, of causation, with conclusions suitable Introduction causation is routinely disputed. -

Handbook on the Management of Munitions Response Actions

United States Office of Solid Waste and EPA 505-B-01-001 Environmental Protection Emergency Response May 2005 Agency Washington, DC 20460 EPA Handbook on the Management of Munitions Response Actions Interim Final 000735 EPA Handbook on The Management of Munitions Response Actions INTERIM FINAL May 2005 000736 This page intentionally left blank. 000737 Disclaimer This handbook provides guidance to EPA staff. The document does not substitute for EPA’s statutes or regulations, nor is it a regulation itself. Thus, it cannot impose legally binding requirements on EPA, States, or the regulated community, and may not apply to a particular situation based upon the circumstances. This handbook is an Interim Final document and allows for future revisions as applicable. 000738 This page intentionally left blank. 000739 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS ..................................................... xiii ACRONYMS ...............................................................xxv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1-1 1.1 Overview...................................................... 1-1 1.2 The Common Nomenclature ....................................... 1-2 1.3 Organization of This Handbook .................................... 1-5 2.0 REGULATORY OVERVIEW ........................................... 2-1 2.1 Regulatory Overview............................................. 2-2 2.1.1 Defense Environmental Restoration Program .................... 2-2 2.1.2 CERCLA ............................................... -

The Impact of Robots on Select Military Operations

The Impact of Robots on Select Military Operations An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Daniel Duffty, Class of 2010 __________________________ Audra Sosny, Class of 2010 __________________________ Date: May 5, 2009 Approved: Professor David Brown, IQP Advisor Abstract The project focused on the current and predicted impact of robots on surveillance, reconnaissance, automated defense, and bomb disposal operations. It investigated existing products and technologies to create a representation of society’s present opinions. The project considered technological, legal, and ethical concerns affecting the advancement of military robotics. It anticipates future developments by analyzing opinions from interviews and data from a survey. The project concluded that society endorses the evolution of robotics not involving lethal force that benefits the military. ii Executive Summary This project, entitled The Impact of Robots on Select Military Operations, studies the current and predicted impact of robots on surveillance, reconnaissance, automated defense, and bomb disposal operations. The project group, Daniel Duffty and Audra Sosny, investigated what robotic technologies are available, how the military presently uses robots, what society thinks about military robots, and what the future of military robots may hold. The use of robotics throughout all facets of society is rapidly increasing. As an emerging field with few developmental restrictions, society’s reaction to and support of robotics varies greatly. The problem is that society supports the military using robots for some purposes, but not all. Another problem is that society supports robots with certain capabilities, but not all. -

Dictionary of Epidemiology, 5Th Edition

A Dictionary of Epidemiology This page intentionally left blank A Dictionary ofof Epidemiology Fifth Edition Edited for the International Epidemiological Association by Miquel Porta Professor of Preventive Medicine & Public Health School of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Senior Scientist, Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica Barcelona, Spain Adjunct Professor of Epidemiology, School of Public Health University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Associate Editors Sander Greenland John M. Last 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective excellence in research, scholarship, and education Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 1983, 1988, 1995, 2001, 2008 International Epidemiological Association, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup-usa.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. This edition was prepared with support from Esteve Foundation (Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain) (http://www.esteve.org) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A dictionary of epidemiology / edited for the International Epidemiological Association by Miquel Porta; associate editors, John M. Last . [et al.].—5th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0-19–531449–6 ISBN 978–0-19–531450–2 (pbk.) 1. -

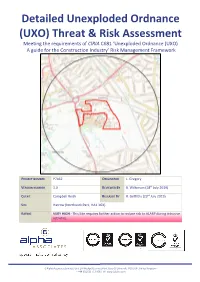

Unexploded Ordnance

Detailed Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) Threat & Risk Assessment Meeting the requirements of CIRIA C681 ‘Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) A guide for the Construction Industry’ Risk Management Framework PROJECT NUMBER P7462 ORIGINATOR L. Gregory VERSION NUMBER 1.0 REVIEWED BY B. Wilkinson (18th July 2019) CLIENT Campbell Reith RELEASED BY R. Griffiths (23rd July 2019) SITE Harrow (Northwick Park, HA1 3GX) RATING VERY HIGH - This Site requires further action to reduce risk to ALARP during intrusive activities. 6 Alpha Associates Limited, Unit 2A Woolpit Business Park, Bury St Edmunds, IP30 9UP, United Kingdom T: +44 (0)2033 713 900 | W: www.6alpha.com Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 3 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 5 STAGE ONE – SITE LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION .............................................................................. 6 Proposed Works ............................................................................................................................. 6 Ground Conditions ........................................................................................................................ -

TR-114 Fire Department Response to Biological Threat at B'nai B'rith

U.S. Fire Administration/Technical Report Series Fire Department Response to Biological Threat at B’nai B’rith Headquarters Washington, DC USFA-TR-114/April 1997 U.S. Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program he U.S. Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion T for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant “lessons learned.” In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire--the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc. In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highlight once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. In some cases, special reports are devel- oped to discuss events, drills, or new technologies which are of interest to the fire service. The reports are sent to fire magazines and are distributed at National and Regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists the USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from the USFA; announce- ments of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters. This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public fire education, building technology, and other related areas. The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an experienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local fire authorities to insure that the assistance and presence of the USFA would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

Improvised Explosive Devices (Ieds) in Iraq: Effects and Countermeasures

Order Code RS22330 February 10, 2006 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in Iraq: Effects and Countermeasures Clay Wilson Specialist in Technology and National Security Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are responsible for many of the more than 2,000 deaths and numerous casualties suffered by U.S. and coalition forces since the invasion of Iraq.1 The bombs have been hidden behind signs and guardrails, under roadside debris, or inside animal carcasses, and encounters with IEDs are becoming more numerous and deadly. The threat has expanded to include vehicle-borne IEDs, where insurgents drive cars laden with explosives directly into a targeted group of service members. DOD efforts to counter IEDs have proven only marginally effective, and U.S. forces continue to be exposed to the threat at military checkpoints, or whenever riding in vehicles in Iraq. DOD reportedly expects that mines and IEDs will continue to be weapons of choice for insurgents for the near term in Iraq, and is also concerned that they might eventually become more widely used by other insurgents and terrorists worldwide. This report will be updated as events warrant. Background Improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, now cause about half of all the American combat casualties in Iraq, both killed-in-action and wounded.2 The Iraqi insurgents make videos of exploding U.S. vehicles and dead Americans and distribute them via the Internet to win new supporters. Outside Iraq, foreign radicals see the images as confirmation that the Americans are vulnerable. -

Bomb Ata Afghanistan Detect Cybersecurity Detection Ata Disrupt Ata Lebanon Tnt Protect Professionalism Success Office Of

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE BUREAU OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY IN PARTNERSHIP WITH BUREAU OF COUNTERTERRORISM EXPERTISE PROTECT ACCOUNTABILITY SAVING LIVES FIRST RESPONDER WEAPONS DETECT AIRPORT OF MASS DESTRUCTION SECURITY ATA BORDER SECURITY ARRESTS SUICIDE VESTS COUNTERMEASURES PROTECTIVE SECURITY DETAIL ANTITERRORISM ASSISTANCE TRAVEL DOCUMENT FRAUD ATTACKS SHRAPNEL REGIONAL STABILITY COMMUNITY-ORIENTED POLICING BOMB ATA AFGHANISTAN DETECT CYBERSECURITY DETECTION ATA DISRUPT ATA LEBANON TNT PROTECT PROFESSIONALISM SUCCESS OFFICE OF SELF RELIANCE ATA TRAINING ANTITERRORISM MANAGEMENT ARRESTS TERRORISM WORKSHOPS NETWORKING ATA ANTITERRORISM KENYA EXPLOSIVES TRAINING INVESTIGATE SEMINARS PREPAREDNESS CHALLENGES ASSISTANCE CRISIS MANAGEMENT ORDNANCE DISPOSAL TRANSNATIONAL NEGOTIATION HOSTAGE ANALYSIS DIPLOMATIC CUTTING-EDGE SECURITY LOYALTY INTERDICTION SKILLS TRAFFICKING SECURITY LAW ENFORCEMENT SKILLS PAKISTAN TECHNOLOGY ACCREDITATION TNT TNT COMMUNICATION BEST PRACTICES SUSPECTS INSTRUCTOR TNT SKILLS COMPETENCY TNT ATA DETER 2012 EVIDENCE TNT DIPLOMATIC SAFETY AIRPORT FISCAL YEAR TNT SECURITY INTERPOL TRIAGE SECURITY IN REVIEW RELATIONSHIPS TACTICS THREATS APPREHEND PROTECTIVE PROTECTIVE OPERATIONS ATA TRAINER ATA DETER COUNTERTERRORISM LEADERS ATA COORDINATION RESCUE LEADER ELITE ATA PLANNING CRISIS SUCCESS ATA SUSPECTS MODERNIZATION PARAGUAY RESPONSE ANALYSIS COMPUTER FORENSICS POLICE ANALYSIS BORDERS ATA TRIAGE GOALS APPREHEND TERRORIST FORENSICS ATA KNOWLEDGE POLICE EMERGENCY ANTITERRORISM MASS-CASUALTY SELF-SUSTAINING BOMBINGS -

Army Courses 2017 - 18

Army Courses 2017 - 18 Sl. Name of Army Training Institution Name of Army Course. No. 1 1 EME,Secunderabad Armourer (B) CI-III PMF Course 2 -do- Welder (B) PMF Course 3 -do- Welder CI—III PMF Course 4 -do- Metal Smith CI-III PMF Course 5 -do- VM(MV)CI-III PMF 6 1 STC, Jabalpur TT Cl-1 7 -do- LMN Cl-1 8 -do- EFS Cl-1 9 3 EME Centre, Bhopal F/Tech Elect (B Veh) 10 AATS, Agra Para Basic Course (JN) 11 EME School, Vadodara Diploma in Automobile Engineering (B Vehicle) 12 -do- Diploma in Automobile Engineering (C Vehicle) 13 -do- Diploma in Elect Engineering (B&C Vehicle) 14 -do- Diploma in Small Arms Engineering 15 -do- Diploma in Instrument Engineering 16 -do- Vehicle Mechanic (Motor Vehicle)Gde-II to I 17 -do- Elect (MV) Gde-II 18 -do- Elect(MV) Gde-I 19 -do- Elect B VehCl -III to II 20 -do- Armourer-I 21 -do- Armourer-II 22 -do- Instrument Mechanic Basic 23 -do- Instrument Mechanic-II 24 -do- Instrument Mechanic-I 25 ASC Centre & College, Bangaluru Transport Supervisory Course (J) 26 -do- Transport Supervisory Course (N) 27 IMA, Dehradun Army Drill Course (ADC) for JCOs & NCOs 28 RVC Centre & School, Meerut National Diploma in Equine Husbandry, Medicine and Surgery (O) Course (NDEHMS) 29 -do- All Arms Equitation & Animal Management (JN)(AEJN) 30 -do- All Arms Basic Riding & Animal Management Course (O) (ABRO) 31 -do- All Arms Basic Riding & Animal Management Course (JN) (ABRJN) 32 -do- All Arms Veterinary First Aid & Animal Hygiene 33 -do- National Diploma in Equine Husbandry Medicine and Surgery (O) Course 34 -do- Dog Handler Course 35 -do- Basic Kennalman 36 Army War College, Mhow Junior Command Course 37 -do- Senior Command Course 38 Army Institute of Physical Training, Pune Asstt. -

American Explosive Ordnance Disposal History

AMERICAN EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL HISTORY Prologue The Beginning Early Years EOD Training Korea to South Vietnam Women in EOD EOD Today PROLOGUE The modern history of disarming bombs began more than 65 years before the British mine and bomb disposal units established the formal profession in World War II we know today as Explosive Ordnance Disposal. Colonel Sir Vivian Dering Majendie, Queen Victoria’s chief inspector of explosives, is recognized as one of the first bomb disposal experts, a term frowned on by today’s technicians. He pioneered many techniques and defused a clockwork-fused bomb at London’s Victoria Station in 1884. In the first World War, the Germans advanced their development of fuzes, including a delayed-action fuze. A more sophisticated version was first tested in the 1936-1937 Spanish Civil War and caused widespread terror in the civilian population. The Germans continued to improve it with their other fuze designs. World War II saw a rapid rise of quantity and sophistication of ordnance never seen in the history of warfare. We now needed professional bomb disposal technicians with the formal training and specialized tools to defeat them. THE BEGINNING On September 7, 1940, Germany began its air war on Britain with 300 bombers dropping 337 tons of bombs on London. Four hundred and forty-eight civilians were killed that afternoon and evening. The aerial bombing continued until May, 1941, but the terror of the bombing did not stop. The Luftwaffe left unexploded bombs, known as UXB, all over London. Some simply failed to detonate, but others had the time-delay fuzes and to continue the terror long after the bombers were gone.