The President and Fellows of Harvard College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels by John William Burgon

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels by John William Burgon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels Author: John William Burgon Release Date: February 22, 2012 [Ebook 38960] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRADITIONAL TEXT OF THE HOLY GOSPELS*** The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels Vindicated and Established By the Late John William Burgon, B.D. Dean of Chichester Arranged, Completed, and Edited by Edward Miller, M.A. Late Rector of Bucknell, Oxon; Editor of the Fourth Edition of Dr. Scrivener's “Plain Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament”; and Author of “A Guide to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament” ¶Ã¹ ¤¿Ö ³w¿¹Â ½ §Á¹ÃÄ÷ 8·Ã¿æ PHIL. i. 1 London George Bell And Sons Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. 1896 Contents Preface. .3 Introduction. 11 Chapter I. Preliminary Grounds. 16 Chapter II. Principles. 30 Chapter III. The Seven Notes Of Truth. 50 Chapter IV. The Vatican And Sinaitic Manuscripts. 78 Chapter V. The Antiquity of the Traditional Text. I. Witness of the Early Fathers. 100 Chapter VI. The Antiquity Of The Traditional Text. II. Witness of the Early Syriac Versions. 141 Chapter VII. The Antiquity Of The Traditional Text. III. Witness of the Western or Syrio-Low-Latin Text. -

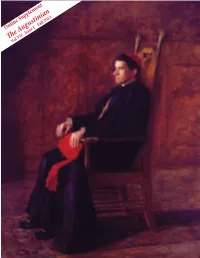

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Kilpatrick' Greek New Testament Edition of 1958

Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New Testament Texts and Studies 11 Series Editor H. A. G. Houghton Editorial Board Jeff W. Childers Christina M. Kreinecker Alison G. Salvesen Peter J. Williams Text and Studies is a series of monographs devoted to the study of Biblical and Patristic texts. Maintaining the highest scholarly standards, the series includes critical editions, studies of primary sources, and analyses of textual traditions. Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New Testament Papers from the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament Edited by H. A. G. Houghton 2014 Gorgias Press LLC, 954 River Road, Piscataway, NJ, 08854, USA www.gorgiaspress.com Copyright © 2014 by Gorgias Press LLC All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise without the prior written permission of Gorgias Press LLC. 2014 ܚ ISBN 978-1-4632-0411-2 ISSN 1935-6927 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (8th : 2013 : University of Birmingham) Early readers, scholars, and editors of the New Testament : papers from the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament / edited by H.A.G. Houghton. pages cm. -- (Texts and studies, ISSN 1935-6927 ; 11) Proceedings of the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, held in the Orchard Learning Resource Centre at the University of Birmingham, March 4-6, 2013. -

In the Shadow of the Kulturkampf

In the Shadow of the Kulturkampf: Perceptions of the Milderungsgesetzen in Dutch Catholic media, from 1880 to 1884 Thomas Kerstens Abstract This is a transnational research on the way Dutch Catholic media perceived the Kulturkampf in Germany from 1880 to 1884. This dissertation examines two Dutch Catholic newspapers and one magazine to explain three things. Firstly, what the main motives of Dutch Catholic media were to report on German social struggles after 1880. Secondly, how the Milder- ungsgesetzen – that were intended to end this social struggle – influenced the content of the reports of Dutch Catholic media. Thirdly, to what extent the German social struggles were put in an international perspective by these media. The conclusion adds to the debate that ques- tions the nineteenth century as the ‘age of the nation state’. In the Shadow of the Kulturkampf: Perceptions of the Milderungsgesetzen in Dutch Catholic media, from 1880 to 1884 Thomas Kerstens 27-06-2014 In the Shadow of the Kulturkampf Thomas Kerstens Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: The Kulturkampf ............................................................................................ 8 Chapter 1.1. Windthorst Speaks ............................................................................ 8 Chapter 1.2. Social Consequences .......................................................................... 12 Chapter 1.3. A Historical Dimension -

Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels

<<•', , /. 20 Iheolagial ^^ i\xt ^ •Axt^^^i %/ :v. ^ PRINCETON, N. J. Diviiion 4.,..&5fe Section __ 5A^^ Number INTRODUCTION THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS PRINTED BY MORRISON AND 01 BB T. & T. CLARK, EDINBURGH LONDON : SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT, AND CO. LIMITED NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER's SONS TORONTO: THE WILLARD TRACT DEPOSITORY INTRODUCTIONJ THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS PATON J. GLOAG, D.D. AUTHOR OB- A COMMENTARY ON THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PAULINE EPISTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CATHOLIC EPISTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE JOHANNINE WRITINGS ETC. ETC. EDINBURGH T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE SJREET 1895 THIS WOEK IS DEDICATED TO MY WIFE, WHO HAS TJNWEAFJEDLY ASSISTED ME IN THIS AND IN ALL MY OTHEK LITERARY LABOURS PREFACE This Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels completes a series of Introductions to the books of the New Testament, in the preparation of which I have been engaged for a quarter of a century. The Introduction to the Acts of the Apostles, with a commentary, was pubHshed in 1870; the Introduction to the Thirteen Pauline Epistles, along with the anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews, in 1874; the Introduction to the Seven Catholic Epistles in 1887 ; the Introduction to the Johannine Writings, especially the Fourth Gospel and the Apiocalypse, in 1891 ; and now the Intro- duction to the Synoptic Gospels in 1895. The design of these Introductions was not to give any explanation of or com- mentary on the sacred text (that to the Acts of the Apostles forming an exception), but to examine the genuineness of the writings, their authorship, the readers to whom they were primarily addressed, their design, their sources,—especially the sources of the historical books,—the language in which they were written, their peculiar style and diction, their charac- teristic features, the integrity of the text, the time when and the place where they were written, and their contents, in short, all that is necessary for their full understanding and intelligent perusal. -

Márcio Manuel Machado Nunes

Márcio Manuel Machado Nunes A ARQUIDIOCESE DE MACEIÓ: UMA ANÁLISE DO PROCESSO DE ESTRUTURAÇÃO DA IGREJA CATÓLICA NO TERRITÓRIO ALAGOANO (1892-1920) Tese de doutoramento em História, ramo de História Contemporânea, orientada pelo Professor Doutor José Pedro Paiva e coorientada pela Professora Doutora Irinéia Maria Franco dos Santos e apresentada ao Departamento de História, Estudos Europeus, Arqueologia e Artes da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra. Outubro de 2020 FACULDADE DE LETRAS DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA A ARQUIDIOCESE DE MACEIÓ: UMA ANÁLISE DO PROCESSO DE ESTRUTURAÇÃO DA IGREJA CATÓLICA NO TERRITÓRIO ALAGOANO (1892-1920) MÁRCIO MANUEL MACHADO NUNES FICHA TÉCNICA Título do Trabalho: A Arquidiocese de Maceió: uma análise do processo de estruturação da Igreja Católica no território alagoano (1892-1920). Orientador: Professor Doutor José Pedro Paiva Coorientadora: Professora Doutora Irinéia Maria Franco dos Santos Área Científica: História Ramo: História Contemporânea Ano de Apresentação: 2020 Em momento oportuno, ouvi um padre da Companhia de Jesus, Ottavio De Bertolis, na Chiesa del Gesù, dizer que oferecera sua tese doutoral ao Sagrado Coração de Jesus. Faço o mesmo: dedico este estudo ao Coração de Jesus Resumo A investigação sobre o processo de estruturação eclesiástica no território alagoano, desde a análise da documentação conservada, principalmente, nos arquivos do Vaticano, possibilita a compreensão de diversos aspetos relacionados com o desenvolvimento da Igreja Católica no Brasil, após a proclamação da República (1889). Eventos da esfera eclesiástica, como as criações de circunscrições, bispados, arcebispados e prelazias, não obstante a Lei de Separação de 1890, estiveram estreitamente alinhados com as disputas políticas e os interesses de governadores, senadores e deputados. -

The Vatican Council from Its Opening to Its Prorogation : Official

' <: * ' f ' - L * * * f < ' : V- A* v ''^'V <* '- *Y- V>'r ' <\ ? l'"f^KI v ' " : ' ' -' y '" '- - -"''' <: , . > ',' ^ i< - < ^' f S v^ /' <* v C \'-' '.' S,i -W^i^tt^'-W:': t '. < ^ ( ,/A.-':;./;vv/;v;^^'/X;^>;o-; ; - <l ,. THE VATICAN COUNCIL, FROM ITS OPENING TO ITS PROROGATION, OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS, DIARY, LISTS OF BISHOPS, &c., &c., &c. PART THE SECOND. ''TABLET OFFICE," 27, WELLINGTON STREET, STRAND BURNS, GATES, AND Co., PORTMAN STREET. INDEX, Preface . I Allocution of Pope Pius IX on the 2nd of December, 1869 . 2 Official Notice of the Opening of the Council . 7 Analysis of the Ordo Concilii CEcumenici . 9 Allocution of Pope Pius IX on the 8th December, 1869, the First Public Session .... Apostolic Letter Multiplies inter of Pope Pius IX of the 27th November, 1869 . Preamble . .21 Chap. I. On the Manner of Life to be followed by those present at the Council . 22 Chap. II. On the Right to bring forward Questions and the manner of so doing . 24 Chap. III. On the Secrecy to be observed in the Council 25 Chap. IV. On the Order of Sitting . 26 Chap. V. Of the Judges of Excuses and Complaints . 28 Chap. VI. Of the Officers of the Council . 29 Chap. VII. Of the General Congregations of the Fathers 31 Chap. VII. Of the Public Sessions . -35 Chap. IX. Of not Leaving the Council . 37 Chap. X. Apostolic Indult concerning Non-residence on the part of those who assist at the Council . .- -37 The Oath taken by the Officials of the Council . 38 Sermon of the Archbishop of Iconium on the 8th December, 1869 39 Ordo Concilii CEcumenici . -

The Augustinian Augustinian Cardinals P

VOLUME VII . ISSUE I the augustinian AUGUSTINIAN CARDINALS P. 3 FANA: THE FEDERATION OF AUGUSTINIANS OF NORTH AMERICA P. 10 AUGUSTINIAN ARTIST FR. RICHARD G. CANNULI: “EVER ANCIENT, EVER NEW” P. 14 table of contents the augustinian . VOLUME VII . ISSUE I contents IN THIS ISSUE P. 3 Augustinian Cardinals On February 18, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI elevated 86-year old Prospero Grech, O.S.A., of Malta, to Cardinal. Dubbed “The Reluctant Cardinal” by the Maltese press, Fr. Prospero, a renowned biblical scholar, author and professor, was caught off guard by the Pope’s request. Similarly, Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., previous to Cardinal Grech, the most recent Augustinian to receive the Red Hat 111 years ago, in 1901 was reluctant to accept a call from Pope Leo XIII to become Apostolic Delegate to the United States. This unusual connection between the two Augustinians is explored. 3 P. 10 IN EVERY ISSUE FANA: The Federation of the Augustinians of North America Features Since 2007, joining the provinces in North America into a federation had been a topic of discussion among the members The Augustinian Fund 24 of the provinces in the United States and Canada. The focus was a new alliance that would leave each province retaining much of their own affairs—but would seek to collaborate in Columns areas of mutual interest for all the provinces. After much work Letter from the Provincial 2 and discussion, friars voted to accept the proposal to form a News and Notes 18 federation. On February 21, 2012, Robert F. Prevost, O.S.A., Prior General of the Augustinian Order in Rome, officially 10 Keeping Track 23 established the Federation of Augustinians of North America. -

063-Santa Maria Del Popolo

(063/7) Santa Maria del Popolo ! The facade of Santa Maria del Popolo Santa Maria del Popolo is a notable Augustinian church located in Rome. It stands to the north side of the Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous squares of the city, between the ancient Porta Flaminia (one of the gates of the Aurelian Walls and the starting point of the Via Flaminia, the road to Ariminum (modern Rimini) and the most important route to the north of Ancient Rome) and the Pincio park. (1) The church is an example of Renaissance architecture with Baroque decoration. History In 1099, a chapel was built by Pope Paschal II to Our Lady, over Roman tombs of the the Domitii family. Tradition claims that emperor Nero was buried on the slope of the Pincian hill by the piazza. There grew a large walnut tree that was infested with deamons that tormented passersby. Pope Paschal II had a dream in which the Bl. Virgin appeared to him and told him to uproot the walnut tree and build a church on the spot. The pope cut down the tree and had Nero’s remains disinterred and thrown into the Tiber at the request of those who lived in the area. The chapel was built were the grave had been. The people, believing the place was haunted by the troubled spirit of Nero and infested by Demons, cheerfully bore the expense of its erection, and the chapel received the name del Popolo ("of the people"). Other sources state that the "popolo" nickname stems from the Latin word populus, meaning "poplar" and probably referring to a tree located nearby. -

The Origin of Mark 16:9-20

THE ORIGIN OF MARK 16:9-20 © 2007 James Edward Snapp, Jr. The pictures have been removed from this edition in order to reduce the size of the file, making it easier to send and receive by e-mail. Most of the pictures can be found online. [Permission is granted to reproduce this material, except for the essay by Dr. Bruce Terry in chapter eight, in electronic form (as a computer-file) and to make printouts on a computer-printer.] TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 2 PART ONE: EXTERNAL EVIDENCE CH. 1: External Evidence from the 2nd and 3rd Centuries 5 CH. 2: External Evidence from the 4th Century 20 CH. 3: External Evidence from the Early 400’s 42 Ch. 4: Some External Evidence from the Mid-400’s and Later 63 CH. 5: External Evidence With the Double-Ending 82 CH. 6: Lectionaries 90 PART TWO: INTERNAL EVIDENCE CH. 7: “Ephobounto Gar” 92 CH. 8: The Style of the Long Ending of Mark (by Dr. Bruce Terry) 96 CH. 9: Is Mk. 16:9-20 Non-Markan? 104 PART THREE: PROPOSED SOLUTIONS CH. 10: Theories about How the Ending was Lost 108 CH. 11: The Unlikelihood of Late Addition 115 CH. 12: The Best Solution 118 CH. 13: Matthew, Luke, and John 122 CH. 14: Closing Remarks 130 Appendix A: Excerpts from the Diatessaron 131 Appendix B: The Short Ending 132 2 Preface In 1881, Westcott & Hort, reinforcing the conclusions of some scholars who preceded them, presented what appeared to be strong and persuasive evidence that the Gospel of Mark originally did not contain Mark 16:9-20.1 Today most commentators deny, often almost casually, that this passage was an original part of the Gospel of Mark.2 That view has affected modern Bible translations and may affect them more noticeably in the future.3 In this book I will offer evidence that the modern consensus should be reconsidered. -

Jules Ferry and Henri Maret: the Battle of Church and State at the Sorbonne, 1879-1884

JULES FERRY AND HENRI MARET: THE BATTLE OF CHURCH AND STATE AT THE SORBONNE, 1879-1884 BY Copyright 2011 TROY J. HINKEL Submitted to the graduate degree program in history and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chairperson Leslie Tuttle Committee members Eve Levin Nathan Wood Luis Corteguera Thomas Heilke Date Defended: April 22, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Troy J. Hinkel certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: JULES FERRY AND HENRI MARET: THE BATTLE OF CHURCH AND STATE AT THE SORBONNE, 1879-1884 Leslie Tuttle Chairperson Date approved: April 22, 2011 ii CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One: The First Confrontation Regarding Higher Education 34 Chapter Two: Ferry’s Success 59 Chapter Three: Maret and the Papal Bull Project 80 Chapter Four: Maret, Ferry, and the Battle for the Sorbonne 115 Chapter Five: The Legacy 141 Appendix: Timeline of Events 165 Bibliography 167 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examins the battle between church and state at the University of Paris, 1879-1884. Jules Ferry, the Minister of Public Instruction for the French Third Republic,wished to secularize education in France during his tenure in this position. Henri Maret,the Dean of the Theology Faculty at the Sorbonne, sought to prevent this. This dissertation examines the ensuing conflict between Ferry and Maret, along with an analysis of the strategies and rationalle uitlized by each. This battle produced ongoing ramifications for larger church and state issues, not only in France, but throughout Europe. -

Uma Missão Para O Império: Política Missionária E O “Novo Imperialismo” (1885-1926)

PROGRAMA INTERUNIVERSITÁRIO DE DOUTORAMENTO EM HISTÓRIA Universidade de Lisboa, ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Universidade Católica Portuguesa e Universidade de Évora Uma Missão para o Império: Política missionária e o “novo imperialismo” (1885-1926) Hugo Filipe Gonçalves das Dores Doutoramento em História Especialidade «Impérios, Colonialismo e Pós-Colonialismo» Tese orientada pelos Professores Doutores António Costa Pinto, Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo e António Matos Ferreira Ano 2014 Tese financiada pela Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, fundos nacionais do MCTES Referência da Bolsa: SFRH/BD/63422/2009 UMA MISSÃO PARA O IMPÉRIO II UMA MISSÃO PARA O IMPÉRIO RESUMO Este trabalho procura compreender o processo histórico de constituição de uma política missionária no império colonial português, num período de crescente internacionalização da problemática da religião e das missões nos contextos imperial e internacional, com a afirmação da liberdade missionária e da tolerância religiosa enquanto princípios essenciais na obra “civilizacional” europeia nos espaços coloniais africanos. A análise da complexidade de um processo que relaciona “missão” e “império”, nas suas múltiplas expressões históricas e manifestações geográficas, é feita a partir de três dimensões essenciais para o debate empreendido pelos actores históricos da época: a dimensão católica, com a centralidade da problemática padroeira e a procura de uma solução concordatária como forma de auxiliar a consolidação da soberania imperial portuguesa em África; a dimensão protestante, vista como “ameaça” ao império, sublinhando as percepções formadas em torno do seu carácter «herético» e, principalmente, «estrangeiro», cruciais para o argumentário colonial português; a dimensão republicana, com as vicissitudes para a definição de uma política missionária nacionalizadora e os limites da aplicabilidade de uma estratégia legislativa iminentemente ideológica.