The Origin of Mark 16:9-20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels by John William Burgon

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels by John William Burgon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels Author: John William Burgon Release Date: February 22, 2012 [Ebook 38960] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRADITIONAL TEXT OF THE HOLY GOSPELS*** The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels Vindicated and Established By the Late John William Burgon, B.D. Dean of Chichester Arranged, Completed, and Edited by Edward Miller, M.A. Late Rector of Bucknell, Oxon; Editor of the Fourth Edition of Dr. Scrivener's “Plain Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament”; and Author of “A Guide to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament” ¶Ã¹ ¤¿Ö ³w¿¹Â ½ §Á¹ÃÄ÷ 8·Ã¿æ PHIL. i. 1 London George Bell And Sons Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. 1896 Contents Preface. .3 Introduction. 11 Chapter I. Preliminary Grounds. 16 Chapter II. Principles. 30 Chapter III. The Seven Notes Of Truth. 50 Chapter IV. The Vatican And Sinaitic Manuscripts. 78 Chapter V. The Antiquity of the Traditional Text. I. Witness of the Early Fathers. 100 Chapter VI. The Antiquity Of The Traditional Text. II. Witness of the Early Syriac Versions. 141 Chapter VII. The Antiquity Of The Traditional Text. III. Witness of the Western or Syrio-Low-Latin Text. -

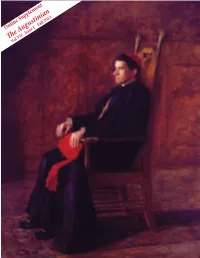

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Kilpatrick' Greek New Testament Edition of 1958

Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New Testament Texts and Studies 11 Series Editor H. A. G. Houghton Editorial Board Jeff W. Childers Christina M. Kreinecker Alison G. Salvesen Peter J. Williams Text and Studies is a series of monographs devoted to the study of Biblical and Patristic texts. Maintaining the highest scholarly standards, the series includes critical editions, studies of primary sources, and analyses of textual traditions. Early Readers, Scholars and Editors of the New Testament Papers from the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament Edited by H. A. G. Houghton 2014 Gorgias Press LLC, 954 River Road, Piscataway, NJ, 08854, USA www.gorgiaspress.com Copyright © 2014 by Gorgias Press LLC All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise without the prior written permission of Gorgias Press LLC. 2014 ܚ ISBN 978-1-4632-0411-2 ISSN 1935-6927 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (8th : 2013 : University of Birmingham) Early readers, scholars, and editors of the New Testament : papers from the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament / edited by H.A.G. Houghton. pages cm. -- (Texts and studies, ISSN 1935-6927 ; 11) Proceedings of the Eighth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, held in the Orchard Learning Resource Centre at the University of Birmingham, March 4-6, 2013. -

A New Descriptive Inventory of Bentley's Unfinished New Testament Project

TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 25 (2020): 111–128 A New Descriptive Inventory of Bentley’s Unfinished New Testament Project* An-Ting Yi, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Jan Krans, Protestantse Theologische Universiteit, Amsterdam Bert Jan Lietaert Peerbolte, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam One of Eldon J. Epp’s areas of expertise is the scholarly history of New Testament textual criticism. He offers an excellent overview of its different stages, including Bentley’s un- finished New Testament project. Yet, many aspects can be refined by studying the -ma terials left by Bentley, preserved at Wren Library of Trinity College (TCL), Cambridge. This contribution offers an up-to-date descriptive inventory of all the remaining archive entries, containing bibliographical information, precise descriptions, relevant second- ary literature, and parts of the reception history. 1. Introduction1 One of Eldon J. Epp’s lifelong interests is the history of New Testament textual scholarship. No- tably his two articles in The New Cambridge History of the Bible not only distinguish periods for the history of the printed Greek New Testament text, but they also become a standard reference for those who want to delve into this issue.2 In these contributions he draws an encompassing picture of the historical developments of text-critical methods of the New Testament, begin- ning from Erasmus until the present day. A key figure contributing to these developments is the renowned eighteenth-century Cambridge classical scholar Richard Bentley (1662–1742). In fact, Epp already mentioned Bentley’s name and his famous Proposals for Printing of 1720 in a 1976 article when tracing the history of the “critical canons” of the New Testament text.3 Since * Our thanks first go to the staff of Wren Library of Trinity College, who generously helped us during our stay in Cambridge, November 2018. -

The President and Fellows of Harvard College

The President and Fellows of Harvard College The Greek Catholic Church in Galicia, 1848-1914 Author(s): JOHN-PAUL HIMKA Reviewed work(s): Source: Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1/4, Ukrainian Church History (2002-2003), pp. 245-260 Published by: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41036853 . Accessed: 03/03/2013 09:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute and The President and Fellows of Harvard College are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Harvard Ukrainian Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Sun, 3 Mar 2013 09:30:43 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The GreekCatholic Church in Galicia, 1848-1914 JOHN-PAUL HIMKA In 1848, according to eparchial schematisms,there were 1,587 Greek Catholic parishes in Galicia embracing2,149,383 faithful.1The archbishopof Lviv and metropolitanof Halych was MykhaïlLevytsTcyi, who was alreadyquite advanced in age and made his residence in the village of Univ. The day-to-dayadministra- tionof Lviv eparchywas entrustedto suffraganbishops: HryhoriiIakhymovych (1841-1848), Ioann BokhensTcyi(1850-1857), and Spyrydon Lytvynovych (1857-1858). -

Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels

<<•', , /. 20 Iheolagial ^^ i\xt ^ •Axt^^^i %/ :v. ^ PRINCETON, N. J. Diviiion 4.,..&5fe Section __ 5A^^ Number INTRODUCTION THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS PRINTED BY MORRISON AND 01 BB T. & T. CLARK, EDINBURGH LONDON : SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT, AND CO. LIMITED NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER's SONS TORONTO: THE WILLARD TRACT DEPOSITORY INTRODUCTIONJ THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS PATON J. GLOAG, D.D. AUTHOR OB- A COMMENTARY ON THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PAULINE EPISTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CATHOLIC EPISTLES AN INTRODUCTION TO THE JOHANNINE WRITINGS ETC. ETC. EDINBURGH T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE SJREET 1895 THIS WOEK IS DEDICATED TO MY WIFE, WHO HAS TJNWEAFJEDLY ASSISTED ME IN THIS AND IN ALL MY OTHEK LITERARY LABOURS PREFACE This Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels completes a series of Introductions to the books of the New Testament, in the preparation of which I have been engaged for a quarter of a century. The Introduction to the Acts of the Apostles, with a commentary, was pubHshed in 1870; the Introduction to the Thirteen Pauline Epistles, along with the anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews, in 1874; the Introduction to the Seven Catholic Epistles in 1887 ; the Introduction to the Johannine Writings, especially the Fourth Gospel and the Apiocalypse, in 1891 ; and now the Intro- duction to the Synoptic Gospels in 1895. The design of these Introductions was not to give any explanation of or com- mentary on the sacred text (that to the Acts of the Apostles forming an exception), but to examine the genuineness of the writings, their authorship, the readers to whom they were primarily addressed, their design, their sources,—especially the sources of the historical books,—the language in which they were written, their peculiar style and diction, their charac- teristic features, the integrity of the text, the time when and the place where they were written, and their contents, in short, all that is necessary for their full understanding and intelligent perusal. -

The Augustinian Augustinian Cardinals P

VOLUME VII . ISSUE I the augustinian AUGUSTINIAN CARDINALS P. 3 FANA: THE FEDERATION OF AUGUSTINIANS OF NORTH AMERICA P. 10 AUGUSTINIAN ARTIST FR. RICHARD G. CANNULI: “EVER ANCIENT, EVER NEW” P. 14 table of contents the augustinian . VOLUME VII . ISSUE I contents IN THIS ISSUE P. 3 Augustinian Cardinals On February 18, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI elevated 86-year old Prospero Grech, O.S.A., of Malta, to Cardinal. Dubbed “The Reluctant Cardinal” by the Maltese press, Fr. Prospero, a renowned biblical scholar, author and professor, was caught off guard by the Pope’s request. Similarly, Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., previous to Cardinal Grech, the most recent Augustinian to receive the Red Hat 111 years ago, in 1901 was reluctant to accept a call from Pope Leo XIII to become Apostolic Delegate to the United States. This unusual connection between the two Augustinians is explored. 3 P. 10 IN EVERY ISSUE FANA: The Federation of the Augustinians of North America Features Since 2007, joining the provinces in North America into a federation had been a topic of discussion among the members The Augustinian Fund 24 of the provinces in the United States and Canada. The focus was a new alliance that would leave each province retaining much of their own affairs—but would seek to collaborate in Columns areas of mutual interest for all the provinces. After much work Letter from the Provincial 2 and discussion, friars voted to accept the proposal to form a News and Notes 18 federation. On February 21, 2012, Robert F. Prevost, O.S.A., Prior General of the Augustinian Order in Rome, officially 10 Keeping Track 23 established the Federation of Augustinians of North America. -

063-Santa Maria Del Popolo

(063/7) Santa Maria del Popolo ! The facade of Santa Maria del Popolo Santa Maria del Popolo is a notable Augustinian church located in Rome. It stands to the north side of the Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous squares of the city, between the ancient Porta Flaminia (one of the gates of the Aurelian Walls and the starting point of the Via Flaminia, the road to Ariminum (modern Rimini) and the most important route to the north of Ancient Rome) and the Pincio park. (1) The church is an example of Renaissance architecture with Baroque decoration. History In 1099, a chapel was built by Pope Paschal II to Our Lady, over Roman tombs of the the Domitii family. Tradition claims that emperor Nero was buried on the slope of the Pincian hill by the piazza. There grew a large walnut tree that was infested with deamons that tormented passersby. Pope Paschal II had a dream in which the Bl. Virgin appeared to him and told him to uproot the walnut tree and build a church on the spot. The pope cut down the tree and had Nero’s remains disinterred and thrown into the Tiber at the request of those who lived in the area. The chapel was built were the grave had been. The people, believing the place was haunted by the troubled spirit of Nero and infested by Demons, cheerfully bore the expense of its erection, and the chapel received the name del Popolo ("of the people"). Other sources state that the "popolo" nickname stems from the Latin word populus, meaning "poplar" and probably referring to a tree located nearby. -

The Text of the New Testament 2Nd Edit

THE TEXT OF THE NEW TESTAMENT Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration BY BRUCE M. METZGER Professor of Mew Testament Language and Literature Princeton Theological Seminary SECOND EDITION OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS Preface to the Second Edition During the four years that have elapsed since the initial publication of this book in 1964, a great amount of textual research has continued to come from the presses in both Europe and America. References to some of these publications were included in the German translation of the volume issued in 1966 under the title Der Text des Neuen Test- aments; Einftihrung in die neutestamentliche Textkritik (Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart) . The second printing of the English edition provides opportunity to introduce a variety of small alterations throughout the volume as well as to include references to more than one hundred and fifty books and articles dealing with Greek manuscripts, early versions, and textual studies of recently discovered witnesses to the text of the New Testament. In order not to disturb the pagination, most of the new material has been placed at the close of the book (pp. 261-73), to which the reader's attention is directed by appropriate cross references. BRUCE M. METZGER February ig68 Preface The necessity of applying textual criticism to the books of the New Testament arises from two circumstances : (a) none of the original documents is extant, and (b) the existing copies differ from one another. The textual critic seeks to ascer- tain from the divergent copies which form of the text should be regarded as most nearly conforming to the original. -

Origin of Mark 16:9-20 Email Edition

1 THE ORIGIN OF MARK 16:9-20 ••• 2009 E-MAIL EDITION ••• © 2008 James Edward Snapp, Jr. [Permission is granted to reproduce this material, except for the essay by Dr. Bruce Terry in chapter nine, in electronic form (as a computer-file) and to make printouts on a computer-printer.] TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 2 PART ONE: EXTERNAL EVIDENCE CH. 1: External Evidence from the 2nd Century 5 CH. 2: External Evidence from the 3rd Century 18 CH. 3: External Evidence from the 4th Century 31 CH. 4: External Evidence from the Early 400’s 57 Ch. 5: Some External Evidence from the Mid-400’s and Later 82 CH. 6: External Evidence With the Double-Ending 105 CH. 7: Lectionary Evidence 116 PART TWO: INTERNAL EVIDENCE CH. 8: “Ephobounto Gar” 120 CH. 9: The Style of the Long Ending of Mark (by Dr. Bruce Terry) 124 CH. 10: Is Mk. 16:9-20 Non-Markan? 132 PART THREE: PROPOSED SOLUTIONS CH. 11: Theories about How the Ending was Lost 137 CH. 12: The Unlikelihood of Late Addition 146 CH. 13: The Best Solution 149 CH. 14: The End of Mark, the Synoptic Problem, and the End of John 153 CH. 15: Closing Remarks 161 Appendix A: Excerpts from the Diatessaron 162 Appendix B: The Short Ending 163 Pictures: MS 274, ℵ’s Decorative Line in Color, Codex L, and Codex W, -- and the End of Mark in Codex 1 The complete form of this essay includes 25 pictures. Most of them have been removed in order to reduce the size of the e-mail attachment. -

The Authenticity of Mark 16:9-20

The Authenticity of Mark 16:9-20 © 2007 James Edward Snapp, Jr. [Permission is granted to reproduce this material, except for the essay by Dr. Bruce Terry in chapter 15, in electronic form (as a computer-file) and to make printouts on a computer-printer.] Considerable effort has been made to accurately cite sources throughout this composition, including materials in the public domain. If somehow an author’s work has not been adequately credited, the author or publisher is encouraged to contact me so that the oversight may be amended. - J.E.S. Be sure to consult the footnotes as you go. Some of them significantly clarify or reinforce the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: Preface (and Notes About Canonicity and Earlier Studies) PART ONE: EXTERNAL EVIDENCE CHAPTER TWO: External Evidence: A Panoramic View CHAPTER THREE: Patristic Evidence CHAPTER FOUR: Lectionary Evidence CHAPTER FIVE: Versional Evidence CHAPTER SIX: A Review of External Evidence CHAPTER SEVEN: Vaticanus and Sinaiticus CHAPTER EIGHT: Codex Bobiensis and the Short Ending CHAPTER NINE: The Long Ending’s Presence in Separate Text-types CHAPTER TEN: The Close Relationships of Witnesses Against the Long Ending CHAPTER ELEVEN: Sixty Early Witnesses PART TWO: MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS CHAPTER TWELVE: How to Lose an Ending CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Explaining the External Evidence PART THREE: INTERNAL EVIDENCE CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “Efobounto Gar” CHAPTER FIFTEEN: The Style of the Long Ending of Mark (by Dr. Bruce Terry) CHAPTER SIXTEEN: A Detailed Look at Internal Evidence Appendix One: A List of Technical Terms and an Explanation of Some Symbols Appendix Two: Mark and Proto-Mark Appendix Three: Some Doctrinal Facets of the Issue Footnotes CHAPTER ONE: Preface For centuries, the Christian church has regarded Mark 16:9-20, the “Long Ending” of Mark (a.k.a. -

The Authenticity of Mark 16:9-20

The Authenticity of Mark 16:9-20 © 2007 James Edward Snapp, Jr. [Permission is granted to reproduce this material, except for the essay by Dr. Bruce Terry in chapter 15, in electronic form (as a computer-file) and to make printouts on a computer-printer.] Considerable effort has been made to accurately cite sources throughout this composition, including materials in the public domain. If somehow an author’s work has not been adequately credited, the author or publisher is encouraged to contact me so that the oversight may be amended. - J.E.S. Be sure to consult the footnotes as you go. Some of them significantly clarify or reinforce the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: Preface (and Notes About Canonicity and Earlier Studies) PART ONE: EXTERNAL EVIDENCE CHAPTER TWO: External Evidence: A Panoramic View CHAPTER THREE: Patristic Evidence CHAPTER FOUR: Lectionary Evidence CHAPTER FIVE: Versional Evidence CHAPTER SIX: A Review of External Evidence CHAPTER SEVEN: Vaticanus and Sinaiticus CHAPTER EIGHT: Codex Bobiensis and the Short Ending CHAPTER NINE: The Long Ending’s Presence in Separate Text-types CHAPTER TEN: The Close Relationships of Witnesses Against the Long Ending CHAPTER ELEVEN: Sixty Early Witnesses PART TWO: MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS CHAPTER TWELVE: How to Lose an Ending CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Explaining the External Evidence PART THREE: INTERNAL EVIDENCE CHAPTER FOURTEEN: “Efobounto Gar” CHAPTER FIFTEEN: The Style of the Long Ending of Mark (by Dr. Bruce Terry) CHAPTER SIXTEEN: A Detailed Look at Internal Evidence Appendix One: A List of Technical Terms and an Explanation of Some Symbols Appendix Two: Mark and Proto-Mark Appendix Three: Some Doctrinal Facets of the Issue Footnotes CHAPTER ONE: Preface For centuries, the Christian church has regarded Mark 16:9-20, the “Long Ending” of Mark (a.k.a.