From Lady Mary to Lady Bute: an Analysis of the Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick the Great's Sexuality – New Avenues of Approach

History in the Making, volume 8, 2021 Frederick the Great’s Sexuality – New Avenues of Approach JACKSON SHOOBERT Frederick the Great’s sexual orientation provides an interesting case study; one that dissects the nature of power, temporality, and sexuality within the confines of elite Prussian eighteenth- century society. Analysis of this subject is significantly complicated by a deep web of adolescent repression which culminated in a level of prudence that still leaves modern scholars without a conclusive definition of Frederick’s sexuality.1 The sexuality of any human forms an important portion of their personality. Ignoring this facet for the sake of a convenient narrative is detrimental to understanding historical characters and the decisions they make.2 Examining how Frederick expressed his sexuality and the inferences this renders about his character will generate a more nuanced understanding without being confined in a broad categorisation as a homosexual. For Frederick, this aspect has been neglected in no small part due to methods he undertook to hide portions of his nature from contemporaries and his legacy. A thorough investigation of the sexuality of Frederick the Great and its interrelations with his personality is therefore long overdue. Frederick the Great, one of the most eminent men of his time, was not an obviously heterosexual man. His sexuality, which has only truly become a legitimate subject for inquiry within the last 60 years, has always been an integral component of his character, permeating from his adolescence unto his death. Despite ground-breaking works by German and Anglo authors in the last decade, the research has barely scraped the surface of what can be learned from Frederick and his sexuality. -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Operatic Reform in Turin

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter tece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, If unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI OPERATIC REFORM IN TURIN: ASPECTS OF PRODUCTION AND STYLISTIC CHANGE INTHEI760S DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Margaret Ruth Butler, MA. -

Newton for Ladies: Gentility, Gender and Radical Culture

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Newton for ladies: gentility, gender and radical culture AUTHORS Mazzotti, Massimo JOURNAL British Journal for the History of Science DEPOSITED IN ORE 27 May 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/28295 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication BJHS 37(2): 119–146, June 2004. f British Society for the History of Science DOI: 10.1017/S0007087404005400 Newton for ladies: gentility, gender and radical culture MASSIMO MAZZOTTI* Abstract. Francesco Algarotti’s Newtonianism for Ladies (1737), a series of lively dialogues on optics, was a landmark in the popularization of Newtonian philosophy. In this essay I shall explore Algarotti’s sociocultural world, his aims and ambitions, and the meaning he attached to his own work. In particular I shall focus on Algarotti’s self-promotional strategies, his deployment of gendered images and his use of popular philosophy within the broader cultural and experimental campaign for the success of Newtonianism. Finally, I shall suggest a radical reading of the dialogues, reconstructing the process that brought them to their religious con- demnation. What did Newtonianism mean to Algarotti? In opposition to mainstream apolo- getic interpretations, he seems to have framed the new experimental methodology in a sensationalistic epistemology derived mainly from Locke, pointing at a series of subversive religious and political implications. Due to the intervention of religious authorities Algarotti’s radical Newtonianism became gradually less visible in subsequent editions and translations. -

Science As a Career in Enlightenment Italy: the Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(S): Paula Findlen Reviewed Work(S): Source: Isis, Vol

Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy: The Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(s): Paula Findlen Reviewed work(s): Source: Isis, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 441-469 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/235642 . Accessed: 08/05/2012 12:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy The Strategies of Laura Bassi By Paula Findlen* When Man wears dresses And waits to fall in love Then Womanshould take a degree.' IN 1732 LAURA BASSI (1711-1778) became the second woman to receive a university degree and the first to be offered an official teaching position at any university in Europe. While many other women were known for their erudition, none received the institutional legitimation accorded Bassi, a graduate of and lecturer at the University of Bologna and a member of the Academy of the Institute for Sciences (Istituto delle Scienze), where she held the chair in experimental physics from 1776 until her death in 1778. -

Science As a Career in Enlightenment Italy: the Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(S): Paula Findlen Source: Isis, Vol

Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy: The Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(s): Paula Findlen Source: Isis, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 441-469 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/235642 . Accessed: 20/03/2013 19:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 19:41:48 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy The Strategies of Laura Bassi By Paula Findlen* When Man wears dresses And waits to fall in love Then Womanshould take a degree.' IN 1732 LAURA BASSI (1711-1778) became the second woman to receive a university degree and the first to be offered an official teaching position at any university in Europe. While many other women were known for their erudition, none received the institutional legitimation accorded Bassi, a graduate of and lecturer at the University of Bologna and a member of the Academy of the Institute for Sciences (Istituto delle Scienze), where she held the chair in experimental physics from 1776 until her death in 1778. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. -

SUL DIBATTITO TRA BETTINELLI E GOZZI, SU DANTE È Noto Che La

JÓZSEF NAGY* SUL DIBATTITO TRA BETTINELLI E GOZZI, SU DANTE È noto che la decisiva rivalutazione dell’eredità letteraria di Dante è avvenu- ta nell’Ottocento. Nel secolo XVIII possiamo essere testimoni dell’ultima fase di questo processo di canonizzazione durato secoli. La disputa tra Saverio Bettinelli e Gasparo Gozzi (nel 1757-58) fu un momento decisivo in tale processo. Nel presen- te studio intendo rilevare i momenti cruciali del dibattito in questione, mostrando anche i tratti principali del contesto filosofico-letterario in cui esso è emerso. 1. Dantismo e antidantismo dal Cinquecento al Settecento In connessione agli antecedenti della disputa Bettinelli-Gozzi, Andrea Batti- stini – che in più occasioni aveva analizzato la fortuna dell’Alighieri1 – nell’in- troduzione a un’antologia di testi sei- e settecenteschi su Dante2 dà un resoconto generale sulla ricezione dantesca nei secoli XVII e XVIII, chiarendo pure i signi- ficati dei termini oscuro e barbaro. L’accusa di oscurità era stata formulata già nel Cinquecento ed è sopravissuta nel Sei- e Settecento, insieme alle qualificazioni (nei confronti delle parole usate da Dante) come «trite e volgari», «umili, ple- bee e laide», «enimmatiche», «stravolte, rancide, rugginose», «noiose, seccantis- sime», «bizzarre», «intemperanti», «confuse, stravaganti»; nel caso di tali accuse evidentemente si tratta di «un genere di requisitorie ispirate al principio estetico * Università ELTE di Budapest Il presente studio è stato realizzato con l’appoggio della borsa di studio postdottorale János Bolyai dell’Accademia Ungherese delle Scienze. Ringraziamenti al Prof. János Kelemen e al – re- centemente deceduto – Prof. Géza Sallay, dell’Un. ELTE di Budapest. 1 Cfr. -

Enlightened Harmonies of the Senses Edward Halley Barnet

Document generated on 09/28/2021 9:58 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada A Perfect Fifth of Blue and Red: Enlightened Harmonies of the Senses Edward Halley Barnet Volume 30, Number 1, 2019 Article abstract In this article, I use Louis-Bertrand Castel’s attempt to create a music of colours URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070634ar as a window into 18th-century debates on the inter-relationship between physics, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070634ar physiology, and sense experience. In part one, I address Castel’s original 1725 proposition to build an “ocular harpsichord,” a musical instrument designed to See table of contents play colour rather than sound. I argue that Castel’s idea relied in equal measure on contemporary music theory, optics, and neurophysiology. In part two, I examine Castel’s attempts to justify his new music experimentally. Though his Publisher(s) purported demonstrations became more eclectic, the core theoretical principles behind his optical music remained the same. In part three, I turn to what should The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada have been the triumph of Castel’s career: his creation of a partially functioning harpsichord in 1755, along with the publication of two proposals for other ISSN sensorial musics in 1753 and 1755. The ostensible failure of Castel’s idea points to the limitations — theoretical, experimental, aesthetic — of his original proposal. 0847-4478 (print) At the same time, their enduring power to inspire spoke to the appeal of music as 1712-6274 (digital) an explanatory framework, encompassing both art and science, body and mind. -

Music in the Classical Era (Mus 7754)

MUSIC IN THE CLASSICAL ERA (MUS 7754) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2016 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 9:30–10:20 M&DA 221 office hours Fridays, 8:30–9:30, or by appointment prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Howe / MUS 7754 Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE OBJECTIVES This course pursues the diversity of musical life in the eighteenth century, examining the styles, genres, forms, and performance practices that have retrospectively been labeled “Classical.” We consider the epicenter of this era to be the mid eighteenth century (1720–60), with the early eighteenth century as its most logical antecedent, and the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century as its profound consequent. Our focus is on the interaction of French, Italian, and Viennese musical traditions, but our journey will also include detours to Spain and England. Among the core themes of our history are • the conflict between, and occasional synthesis of, French and Italian styles (or, rather, what those styles came to symbolize) • the increasing independence of instrumental music (symphony, keyboard and accompanied sonata, concerto) and its incorporation of galant and empfindsam styles • the expansion and dramatization of binary forms, eventually resulting in what will later be termed “sonata form” • signs of wit, subjectivity, and the sublime in music of the “First Viennese Modernism” (Haydn, Mozart, early Beethoven). We will seek new critical and analytical readings of well-known composers from this period (Beethoven, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Pergolesi, Scarlatti) and introduce ourselves to the music of some lesser-known figures (Alberti, Boccherini, Bologne, Cherubini, Dussek, Galuppi, Gossec, Hasse, Hiller, Hopkinson, Jommelli, Piccinni, Rousseau, Sammartini, Schobert, Soler, Stamitz, Vanhal, and Vinci, plus at least two of J. -

Fall 2008 Vol

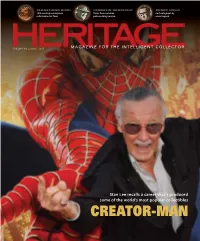

SEBASTIANO RICCI FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT BUDDY HOLLY 18th-century masterpiece Prints from secretive Last autograph by rediscovered in Texas palm-reading session music legend Fall 2008 Vol. 2, Issue 1 $9.95 MAGAZINE FOR THE INTELLIGENT COLLECTOR Stan Lee recalls a career that’s produced some of the world’s most popular collectibles CREATOR-MAN CONTENTS YOU SEE SENTIMENTAL VALUE. Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) with Marco Ricci (1676-1730) The Vision of St. Bruno, circa 1700 Oil on canvas 5 37 x 48 ⁄8 in. HIGHLIGHTS Estimate: $600,000-$800,000 Fine Art Signature Auction #5002 (page 36) THE VISION OF ST. BRUNO WE SEE REPLACEMENT VALUE. Italian masterpiece that once belonged to 36 famed collector Francesco Algarotti and IN EVERY ISSUE a merchant who outfitted Lewis & Clark rediscovered in Texas 4 Staff & Contributors Auction Calendar COVER STORY: STAN LEE 6 For more than 60 years, Stan Lee has stood HAVE YOU HAD YOUR ESTATE APPRAISED? Credentialed ISA appraisers 8 Remember When … behind some of the most iconic characters see the world in a different light. Our years of practical training provide us with a 46 in pop culture discriminating eye and in-depth knowledge of personal property value. While many News people have items that are covered under homeowners or renters insurance, few 10 have their entire households covered adequately. Think about it. If you lost everything Events Calendar ARTISTIC LeaPS you own, what would the replacement value be for all of your belongings? An appraisal 73 Fifty years after launching his career, Mort report written to ISA appraisal report writing standards not only brings you peace of Experts Künstler recognized as one of America’s mind, we deliver a document that brings legitimacy to a potential claim and assistance 74 54 in protecting your most treasured and least likely covered heirlooms. -

Europe Is What Unites Us: the Enlightenment

EUROPE IS WHAT UNITES US: THE ENLIGHTENMENT Europe is able to create high cultural, intellectual, literary and artistic trends and movements, that brought us so much welfare and prosperity. E.g. the Age of Enlightenment, an elite cultural and very complex movement of intellectuals in 18th century, that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange, common goals of progress, tolerance and opposed intolerance and abuses in Church and state. Originating about 1650–1700, it was sparked by philosophers Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), John Locke (1632–1704), and Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) and by mathematician Isaac Newton (1643–1727). Ruling princes often endorsed and fostered Enlightenment figures and even attempted to apply their ideas of government. The Enlightenment flourished until about 1790–1800 and it was focussed on functionality and conceived art and beauty as side issues, a personal hobby. The radical Enlightenment is under the impression that reason can only be the slave of the passions. After 1800 the emphasis on reason gave way to Romanticism's emphasis on emotion and a Counter-Enlightenment gained force. The center of the Enlightenment was France, where it was based in the salons and culminated in the great Encyclopédie (1751–72) edited by Denis Diderot (1713–1784) with contributions by hundreds of leading Die Tafelrunde by Adolph von Menzel. The oval domed philosophers (intellectuals) such as Voltaire (1694–1778), who stayed "Marble Hall" in Sanssouci, the summer palace of between 1750 and 1753 in Sanssouci, the summer palace of Frederic the Frederic the Great, is the principal reception room of the palace.