Portfolio Effects in Conglomerate Mergers 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie's Group Limited

Charlie’s Group Limited Independent Adviser’s Report On the full takeover offer from Asahi Beverages New Zealand Limited APPENDIX July 2011 024 Table of Contents Glossary Glossary..........................................................................................................................................................................................3 Glossary 1. Terms of the Asahi Offer ......................................................................................................................................................5 1.1 Background to the Offer ...............................................................................................................................................5 Term Definition 1.2 Details of the Asahi Offer...............................................................................................................................................6 90% Minimum Acceptance Condition A condition of the Asahi Offer that requires that Asahi receive acceptances to take its 1.3 Requirements of the Takeovers Code...........................................................................................................................7 shareholding to 90% or more of the Charlie’s Group shares on issue 2. Scope of the Report..............................................................................................................................................................8 2.1 Purpose of the Report ..................................................................................................................................................8 -

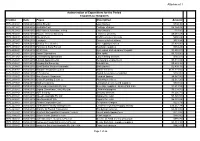

Creditor Date Payee Description Amount Authorisation Of

Authorisation of Expenditure for the Period 1/04/2015 to 30/04/2015 Creditor Date Payee Description Amount 1775.2008-01 01/04/2015 Alinta Energy Gas charges $704.30 1775.2019-01 01/04/2015 Australia Post Postage charges $5,154.29 1775.2033-01 01/04/2015 BOC Gases Australia Limited Gas charges $23.50 1775.2034-01 01/04/2015 Boyan Electrical Services Electrical services $8,681.48 1775.2049-01 01/04/2015 City Of Perth BA/DA archive retrievals $690.49 1775.2072-01 01/04/2015 Landgate Gross rental valuations $653.84 1775.2074-01 01/04/2015 Dickies Tree Service Tree lopping services $7,491.00 1775.2085-01 01/04/2015 Farinosi & Sons Pty Ltd Hardware supplies $334.22 1775.2096-01 01/04/2015 GYM Care Gym wipes and equipment repairs $1,450.91 1775.2110-01 01/04/2015 Jason Signmakers Bike racks $3,729.00 1775.2119-01 01/04/2015 Line Marking Specialists Line marking services $765.07 1775.2120-01 01/04/2015 LO-GO Appointments Temporary employment $3,318.89 1775.2126-01 01/04/2015 Mayday Earthmoving Bobcat hire $5,245.90 1775.2134-01 01/04/2015 Boral Bricks Western Australia Brick pavers $2,409.13 1775.2136-01 01/04/2015 Mindarie Regional Council Waste services $131,171.85 1775.2138-01 01/04/2015 C Economo Award for service recognition $150.00 1775.2158-01 01/04/2015 Non Organic Disposals Rubbish tipping $4,587.00 1775.2159-01 01/04/2015 Oasis Plumbing Services Plumbing services $6,517.20 1775.2189-01 01/04/2015 SAS Locksmiths Locksmith services and supplies $993.52 1775.2190-01 01/04/2015 Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd Beverage supplies - Beatty Park -

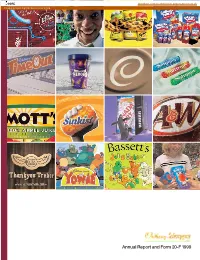

1999 Annual Report

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB Annual Report and Form 20-F 1999 Contents Page Strategy Statement 1 Corporate Highlights 2 Financial Highlights 3 1 Business Review 1999 5 2 Description of Business 23 3 Operating and Financial Review 33 4 Report of the Directors 57 5 Financial Record 77 6 Financial Statements 83 7 Shareholder Information 131 Glossary 141 Cross reference to Form 20-F 142 Index 144 The images used within this Annual Report and Form 20-F are taken from advertising campaigns and websites which promote our brands worldwide. They demonstrate how we communicate the appeal of our brands in a wide range of markets. “Sunkist” is a registered trademark of Sunkist Growers, Inc. This is the Annual Report and Form 20-F of Cadbury Schweppes public limited company for the year ended 2 January 2000. It contains the annual report and accounts in accordance with UK generally accepted accounting principles and regulations and incorporates the annual report on Form 20-F for the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US. A Summary Financial Statement for the year ended 2 January 2000 has been sent to all shareholders who have not elected to receive this Annual Report and Form 20-F. The Annual General Meeting will be held on Thursday, 4 May 2000. The Notice of Meeting, details of the business to be transacted and arrangements for the Meeting are contained in the separate Annual General Meeting booklet sent to all shareholders. The Company undertook a two for one share split in May 1999. -

Bringing the World Moments Of

BRINGING THE WORLD MOMENTS OF ANNUAL REPORT AND FORM 20-F 2001 Contents Page 1 Business Review 2001 1 2 Description of Business 29 3 Operating and Financial Review 39 4 Report of the Directors 59 5 Financial Record 79 6 Financial Statements 87 7 Shareholder Information 141 Glossary 159 Cross reference to Form 20-F 160 Index 162 This is the Annual Report and Form 20-F of Cadbury Schweppes public limited company for the year ended 30 December 2001. It contains the annual report and accounts in accordance with UK generally accepted accounting principles and regulations and, together with the Form 20-F to be filed in April 2002 with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, incorporates the annual report on Form 20-F for the US Securities and Exchange Commission. A Summary Financial Statement for the year ended 30 December 2001 has been sent to all shareholders who have not elected to receive this Annual Report and Form 20-F. The Annual General Meeting will be held on Thursday, 9 May 2002. The Notice of Meeting, details of the business to be transacted and arrangements for the Meeting are contained in the separate Annual General Meeting booklet sent to all shareholders. 1 Business Review 2001 Group Strategy Statement 2 This is Cadbury Schweppes! 4 Corporate and Financial Highlights 6 Moments of Delight – Confectionery 8 1 Chairman’s Statement 10 Moments of Delight – Beverages 12 Chief Executive Officer’s Review 14 A Snapshot of our Industry 20 Chief Operating Officer’s Review 22 Corporate and Social Responsibility 26 Contents Inside Front Cover Glossary 159 Cross reference to Form 20-F 160 Index 162 Annual Report and Form 20-F 2001 Cadbury Schweppes 1 WE ARE passionate ABOUT TO CREATE BRANDS BRANDS THAT BRING THE delight AND A SPLASH 2 Cadbury Schweppes Annual Report and Form 20-F 2001 WORKING TOGETHER THAT PEOPLE love. -

Gigs | Music | Arts | FILM | TV | Games | Gadgets | Food | BARS | Gear

Gigs | Music | Arts | FILM | TV | GAMES | GADGETS | FOOD | BARS | GEAR SHIT WORTH DOING FREE 13 - 19 MAR 2013 . NZ’S ONLY FREE WEEKLY STREET PRESS . ISSUE 451 . GROOVEGUIDE.CO.NZ BOWIE - GGQTR-11_3_13_BOWIE - GGQTR-11_3_13 11/03/2013 15:39 Page STROKES1 - GGQTR-11_3_13_STROKES - GGQTR-11_3_13 11/03/2013 09:52 The Strokes Comedown The Next Day Machine New album Out Now Including One Way Trigger & All The Time David Bowie’s first Album in 10 Years. Limited edition deluxe CD features 14 new songs including 'Where Are We Now?' and 'The Stars (Are Out Tonight)' Plus three bonus tracks ALBUM OUT NOW Available from Available from SHIT WOrtH KNOwing grooveguide.co.nz NEWS MORNING GLORY 95bFM has announce the new host of Morning Glory, Esther MacIntyre. Esther began her tenure at bFM as a volunteer on the News team in 2010 and has honed her experience across new music & current affairs as 95bFM Breakfast Producer, Wire host, and Wednesday 1-4 host. Esther has been a regular fill-in on Morning Glory since 2011 and is looking forward to bringing you the show’s upbeat and topical vibe every weekday. The daily format of Morning Glory will continue to deliver a mix of arts, culture, interviews & features, and music. Fashion to food, book reviews to Scan the QR code with your international artists. Esther will begin hosting full- smartphone to go to Groove Guide’s time on Mon 18 Mar. mobile website for breaking news, reviews, interviews and more features. MORNING GLORY IS 9AM-12PM WEEKDAYS ON 95BFM. FORMerly KNOwN aS Snoop Lion, formerly known THNKS FR TH MMRS as Snoop Dogg, will release his As we mentioned a few weeks ago Fall Out Boy are highly anticipated new album, back from their hiatus with a new single and an up Reincarnated, in April. -

Verification Or Certification of a Document

ASIC registered agent number 109 lodging party or agent name Grant Thornton office, level, building name or P0 Box no. GPO BOX 1008 street number & name suburb/city BRISBANE QLD telephone 0732220200 facsimile 073222 0446 OX number suburb/city Australian Securities & Investments Commission form 911 Corporations Act 2001 Regulation 1.0.16 corporation name H & S Vision Pty Ltd A.C.N. orA.R.B.N. 102 250 911 D document title Minutes of First Meeting of Creditors relevant section or subsection 436E of the corporations Act 2001 D E I verify that the attached document marked ( ) is the original document. lãJ I certify that the attached document marked ( 'A" ) is a true copy of the original document. print name Shaun Capacity: Voluntary Administrator sign here date 04/09/2013 A S & Forms Manager I C Form being prepared OnIe/Itme: 04-09-2013 15:04:38 Reference Id: 87581233 F 5011 Corporations Act 2001 s436E, 439A Corporations Regulations 2001 5.6.11.(2), 5.6.27 C L Registered liquidator number 344636 Registered liquidator name SHAUN CHRISTOPHER MCKINNON C Company name H & S VISION PTY LTD 102 250 911 S Date of meeting Are 21-08-2013 the minutes being lodged for a meeting Convened under s436E, or s439A of the Corporations Act 2001? Yes A This form has been authenticated by Name SHAUN CHRISTOPHER MCKINNON This form has been submitted by Name Date For more help or information Web w,'.v.asic.qov.au Ask a question? w.vw.asic.poy.aufouestiaa Telephone 1300 300 630 ASIC Form 5011 Ref 87581233 Page 1 of 1 MINUTES OF CONCURRENT FIRST -

Western Australian Industrial Gazette PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY

1251 Western Australian Industrial Gazette PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Sub-Part 6 WEDNESDAY, 27 APRIL, 2005 Vol. 85—Part 1 THE mode of citation of this volume of the Western Australian Industrial Gazette will be as follows:— 85 W.A.I.G. CUMULATIVE CONTENTS AND DIGEST APPEAR AT THE END OF THIS PUBLICATION INDUSTRIAL APPEAL COURT—Appeal against decision of Full Bench— 2005 WAIRC 00759 APPEAL AGAINST DECISION OF THE FULL BENCH IN FBA 2 OF 2004 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL APPEAL COURT PARTIES BUDGET AIRCONDITIONING APPELLANT -v- STEVEN RAINSFORD PENN RESPONDENT CORAM PULLIN J (Presiding Judge) HEENAN J LE MIERE J DATE OF ORDER MONDAY, 21 MARCH 2005 FILE NO/S IAC 8 OF 2004 CITATION NO. 2005 WAIRC 00759 Result Appeal discontinued. Representation Appellant Mr W.W.W. Yu Respondent Mr K Trainer Order Having heard Mr W.W.W Yu on behalf of the Appellant and Mr K Trainer on behalf of the Respondent, THE COURT HEREBY ORDERS THAT: 1. This Appeal is discontinued, and 2. There be no Order as to costs. (Sgd.) J.A. SPURLING, Clerk Of The Court. 1252 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL GAZETTE 85 W.A.I.G. FULL BENCH—Appeals against decision of Commission— 2005 WAIRC 00743 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION PARTIES CANON FOODS APPELLANT -and- HAYLEY MAREE MCCOLL RESPONDENT CORAM FULL BENCH HIS HONOUR THE PRESIDENT P J SHARKEY CHIEF COMMISSIONER A R BEECH COMMISSIONER S WOOD DATE FRIDAY, 18 MARCH 2005 FILE NO. FBA 42 OF 2004 CITATION NO. 2005 WAIRC 00743 CatchWords Industrial Law (WA) - appeal against the decision of a single Commissioner - probationary period - warnings - termination of employment - credibility of witnesses - substantial fairness - Industrial Relations Act 1979 (as amended), s29(1)(b)(i), s29(1)(b)(ii), s49. -

Watersmart Guidebook

WATERSMART GUIDEBOOK A Water-Use Efficiency Plan Review Guide for New Businesses 2008 This page intentionally left blank. Watersmart Guidebook FEF A Water-Use Efficiency Plan-Review Guide for New Businesses East Bay Municipal Utility District 2008 Copyright © 2008, East Bay Municipal Utility District. All rights reserved. East Bay Municipal Utility District 375 11th Street, Oakland CA 94607 Phone: 510-287-1675 Fax: 510-287-1883 E-mail: [email protected] DISCLAIMER: This guidebook is provided exclusively for general education and infor- mational purposes and as a public service by the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EB- MUD). Although we at EBMUD try to ensure all information is accurate and complete, information can change without notice, and EBMUD makes no claims, promises, or guar- antees about the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of this guidebook, and all its infor- mation and related materials are provided “as is.” By using this guidebook, you assume the risk that the information and materials in the guidebook may be incomplete, inaccurate, or out-of-date, or may not meet your needs and requirements. Users should not assume the information in this guidebook to be completely error-free or to include all relevant infor- mation, or use it as an exclusive basis for decision-making. The user understands and ac- cepts the risk of harm or loss to the user from use of this information. You are authorized to view this guidebook for your use and to copy any part of it. In exchange for this autho- rization: (i) you agree not to sell or publish the guidebook without first receiving written permission from EBMUD; and (ii) you waive, release, and covenant not to sue EBMUD and all others affiliated with developing this guidebook from any liability, claims, and ac- tions, both known and unknown, for any losses, damage, or equitable relief you may now have a right to assert or later acquire, arising from such use or reliance on the guidebook. -

Thursday, 3 July 2014

No. 50 3091 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 3 JULY 2014 CONTENTS Page Appointments, Resignations, Etc. ............................................ 3092 Corporations and District Councils—Notices.......................... 3135 Development Act 1993—Notice ............................................. 3093 Environment Protection Act 1993—Notices ........................... 3101 Fisheries Management Act 2007—Notices ............................. 3115 Geographical Names Act 1991—Notice ................................. 3117 Housing Improvement Act 1940—Notices ............................. 3118 Land Acquisition Act 1969—Notice ....................................... 3117 Libraries Board of South Australia—Notice ........................... 3120 Mining Act 1971—Notice ....................................................... 3117 Partnership Act 1891—Notice ................................................. 3139 Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000—Notice ............ 3124 Proclamations .......................................................................... 3127 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................. 3138 REGULATIONS Evidence Act 1929 (No. 198 of 2014) ................................. 3129 Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Land Rights Act 1981— (No. 199 of 2014) ......................................................... 3131 (No. 200 -

Beverage Sector Initiation Research Analysts INITIATION

09 December 2014 Asia Pacific/Japan Equity Research Beverage (Food (Japan)) / MARKET WEIGHT Beverage Sector Initiation Research Analysts INITIATION Masashi Mori 81 3 4550 9695 [email protected] MARKET WEIGHT on sector, most positive on Asahi Initiate coverage: We initiate coverage of Japan’s beverage sector, with a NEUTRAL rating on Asahi Group Holdings (2502, TP ¥4,050) and Suntory Beverage & Food (SBF; 2587, TP ¥4,500), and an UNDERPERFORM rating on Kirin Holdings (2503, TP ¥1,400). All three stocks have risen recently, pulled up by market factors. We think further upside may be limited, based on a valuation comparison with global brewers and soft drink makers that factors in profit growth potential, ROE, and shareholder returns. Moreover, for all three companies our OP estimates for FY15 onward are lower than the I/B/E/S consensus; we therefore assign the beverage subsector a MARKET WEIGHT investment stance. The shortage in our forecasts versus consensus is smallest for Asahi at 2%, compared with 9% for Kirin and 5% for SBF. Our top pick in the Japanese beverage sector is Asahi for its favorable balance between steady profit growth and shareholders returns. Japan market: We think the competitive landscape for domestic brewers and soft drink makers will be much the same in 2015 as in 2014. While we will be closely monitoring business plans due out in Jan–Feb 2015, 2015 is the final year of the current medium term plan for all three companies and we do not expect much change in business or product strategies. Kirin should continue to lag its rivals in both the beer and soft drink markets. -

Top 150 Global Licensors Report for the Very First Time, Debuting at No

APRIL 2018 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 2 Plus: The Walt Disney Company Tops Report at $53B 12 Licensors Join the Top 150 GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Powered by Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. WHERE FASHION AND LICENSING MEET The premier resource for licensed fashion, sports, and entertainment accessories. Top 150 Global Licensors GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. by PATRICIA DELUCA irst, a word of warning for prospective licensees: Crayola Experience. And with good reason. The Crayola if you wish to do business with Crayola, wear Experience presents the breadth and depth of the comfortable shoes. Initial business won’t be Crayola product world in a way that needs to be seen. Fconducted through a series of email threads or Currently, there are four Experiences in the U.S.– conference calls, instead, all potential partners are asked Minneapolis, Minn.; Orlando, Fla.; Plano, Texas; and Easton, to take a tour of the company’s indoor family attraction, Penn. The latter is where the corporate office is, as well as the nearby Crayola manufacturing facility. -

Page 1 1 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Company Name: Asahi Breweries

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Company name: Asahi Breweries, Ltd. President: Hitoshi Ogita Stock Ticker number: 2502 Stock Exchanges: Tokyo and Osaka (First Section each) Contact: Public Relations Department Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Phone: +81-3-5608-5126 Acquisition of Australian Beverage Business from Cadbury December 24, 2008, Tokyo, Japan – Asahi Breweries, Ltd. (“Asahi”) is pleased to announce that it has reached a conditional agreement with Cadbury plc (“Cadbury”; Head Office: London, UK; CEO: Todd Stitzer) to acquire the Australian beverage business owned and operated by Cadbury (“Schweppes Australia”). 1. Acquisition of Schweppes Australia Asahi expects to acquire Schweppes Australia in the first half of fiscal year 2009, ending December, following which Schweppes Australia will become a wholly owned subsidiary of Asahi. The agreement with Cadbury is subject to normal regulatory and other closing conditions, including Foreign Investment Review Board approval. In addition, the agreement is subject to a right of negotiation granted to The Coca-Cola Company (“TCCC”) in 1999. Under this provision, TCCC has the right until March 2009 to negotiate with Cadbury regarding a potential acquisition of the Schweppes Australia. If Cadbury and TCCC do not enter into an agreement with respect to Schweppes Australia, then Asahi will enter into a binding sale and purchase agreement with Cadbury. Asahi expects that all other pre-conditions to closing will have been completed by 30 April 2009. The total purchase price for this transaction is expected to be 1,185 million Australian dollars (approximately 73.5 billion Japanese Yen)* subject to certain price adjustments based on cash and cash deposits and interest-bearing liabilities and others.