The Regulation of Video-On-Demand: Consumer Views on What Makes Audiovisual Services “TV-Like” – a Qualitative Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TPTV Schedule Dec 10Th - 16Th 2018

TPTV Schedule Dec 10th - 16th 2018 DATE TIME PROGRAMME SYNOPSIS Mon 10 6:00 The Case of 1949. Drama. Made at Merton Park Studios, based on a true story, Dec 18 Charles Peace directed by Norman Lee. The film recounts the exploits through the trial of Charles Peace. Starring Michael Martin-Harvey. Mon 10 7:45 Stagecoach West A Place of Still Waters. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who Dec 18 run a stagecoach line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 10 8:45 Glad Tidings 1953. Drama. Colonel's adult children object to him marrying an Dec 18 American widow. Starring Barbara Kelly and Raymond Huntley. Mon 10 10:05 Sleeping Car To 1948. Drama. Director: John Paddy Carstairs. Stars Jean Kent, Bonar Dec 18 Trieste Colleano, Albert Lieven & David Tomlinson. Agents break into an embassy in Paris to steal a diary filled with political secrets. Mon 10 11:55 Hell in the Pacific 1968. Adventure. Directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin Dec 18 and Toshiro Mifune. During World War II, an American pilot and a Japanese navy captain are deserted on an island in the Pacific Ocean Mon 10 14:00 A Family At War 1971. Clash By Night. Created by John Finch. Stars John McKelvey & Dec 18 Keith Drinkel. A still-blind Phillip encounters an old enemy who once shot one of his comrades in the Spanish Civil War. (S2, E16) Mon 10 15:00 Windom's Way 1957. Drama. Directed by Ronald Neame. -

Itv and Virgin Media Agree Long Term Commercial Partnership

ITV AND VIRGIN MEDIA AGREE LONG TERM COMMERCIAL PARTNERSHIP ITV and Virgin Media have today signed an innovative new three-year deal that drives increased value for both businesses and provides Virgin TV customers with an enhanced viewing experience across all of ITV’s channels and services. The deal, which will result in a new commercial relationship between the two companies, includes an expanded range of ITV content across all Virgin Media’s current and planned platforms, an enhanced advertising and marketing commitment from Virgin Media across ITV’s family of channels, as well as an increased presence and additional promotion for the ITV brand, and ITV’s great programmes, on Virgin Media’s channels. The agreement also includes the following: • The supply of all ITV channels in SD and HD for in-home and out-of-home viewing • All 4K programming on ITV including future sporting events • An expanded supply of on-demand rights, extending the viewing window and offering access to premium ITV box sets • Support for new functionality on the Virgin TV platform such as the ability to “start over” and “replay” programmes • Carriage of the ITV Hub app on Virgin Media set top boxes • An agreement to work together to enable cloud-based recordings in future While an important feature of the agreement is a deeper commercial relationship between the two companies, it also maintains both parties’ respective long-held positions on the issue of retransmission fees for the future. Carolyn McCall, CEO of ITV, said: “Viewers and customers are at the heart of everything we do at ITV and this focus will become increasingly important as we continue to make our fantastic content available to audiences wherever they are, and whenever they want to watch. -

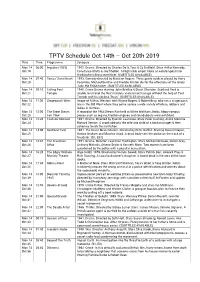

TPTV Schedule Oct 14Th – Oct 20Th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 14 06:00 Impulse (1955) 1955

TPTV Schedule Oct 14th – Oct 20th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 14 06:00 Impulse (1955) 1955. Drama. Directed by Charles De la Tour & Cy Endfield. Stars Arthur Kennedy, Oct 19 Constance Smith & Joy Shelton. A Night club singer tricks an estate agent into thinking he killed a jewel thief. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 07:40 Forces' Sweetheart 1953. Comedy directed by Maclean Rogers. Three goofy soldiers played by Harry Oct 20 Secombe, Michael Bentine and Freddie Frinton vie for the affections of the lovely Judy, the ENSA-tainer. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 09:10 Calling Paul 1948. Crime Drama starring John Bentley & Dinah Sheridan. Scotland Yard is Oct 21 Temple unable to unravel the 'Rex' murders and cannot manage without the help of Paul Temple and his sidekick 'Steve'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 14 11:00 Stagecoach West Image of A Man. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who run a stagecoach Oct 22 line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 14 12:00 The Great Steam A record of the 1964 Steam Fair held at White Waltham, Berks. Many famous Oct 23 Fair 1964 pieces such as organs, traction engines and roundabouts were exhibited. Mon 14 12:20 Cash on Demand 1961. Drama. Directed by Quentin Lawrence. Stars Peter Cushing, Andre Morell & Oct 24 Richard Vernon. A crook abducts the wife and child of a bank manager & then schemes to rob the institution. Mon 14 14:00 Scotland Yard 1961. The Never Never Murder. Directed by Peter Duffell. -

A New Level to Pay TV Netflix Integration January 2019 Sky Ultimate on Demand Introduction

Sky Ultimate On Demand A new level to Pay TV Netflix Integration January 2019 Sky Ultimate On Demand Introduction In November 2018 Sky joined the long list of Pay TV operators that offer Netflix to their subscribers. With Movistar also launching at the end of 2018 in Spain, and OSN (Middle East) set for launching in 2019 we may have reached a tipping point with operators approach to Netflix. Operators who have been strong in building their own channels and services are now willing to fully embrace the importance of Netflix to their customers, and the belief that they are not competing for subscribers outweighs any issues over their competition for content and customer revenue. “We want Sky Q to be the number one destination for TV fans. Partnering with Netflix means we will have all the best TV in one great value pack, making it even easier for you to watch all of your favourite shows.” Stephen van Rooyen Chief Executive, Sky UK & Ireland Insight - Sky Ultimate On Demand January 2019 2 Sky Ultimate On Demand Netflix and Pay TV Operators Netflix’s first Pay TV integrations were in 2013 with TiVo boxes offered by Virgin Media (UK) and Com Hem (Sweden). Virgin were the first to add Netflix to their set-top-box in November 2013, and more have followed as Netflix’s market position has grown and operators realised they can work together. Operators have been adding Netflix to their own services to varying degrees, with variations to the user experience, billing, UHD availability and the pricing proposition. -

Betsson Ab (Publ) Prospectus Regarding Listing of Senior Unsecured Floating Rate Bonds 2019/2022

BETSSON AB (PUBL) PROSPECTUS REGARDING LISTING OF SENIOR UNSECURED FLOATING RATE BONDS 2019/2022 ISIN: SE0013110814 19 November 2019 -- 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION This prospectus (the “Prospectus”) has been prepared by Betsson AB (publ) (the “Company” or “Betsson”), reg. no. 556090-4251, in relation to the application for admission to trading of the Company’s SEK 1,000,000,000 senior unsecured floating rate bonds 2019/2022 with ISIN SE0013110814 (the “Bonds”), issued on 26 September 2019 (the “First Issue Date”) in accordance with the terms and conditions for the Bonds (the “Terms and Conditions”) (the “Bond Issue”), on the Corporate Bond List at Nasdaq Stockholm AB (“Nasdaq Stockholm”). The Company may at one or more occasions after the Issue Date issue Subsequent Bonds under the Terms and Conditions, until the total amount under the Subsequent Bond Issue(s) and the Bond Issue equals SEK 2,500,000,000. References to the Company, Betsson or the Group refer in this Prospectus to Betsson AB (publ) and/or its subsidiaries, unless otherwise indicated by the context. References to “SEK” refer to Swedish Kronor. Terms defined in the Terms and Conditions beginning on page 30 shall have the same meanings when used in this Prospectus unless expressly stated otherwise following from the context. This Prospectus has been approved and registered by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (Sw. Finansinspektionen) (the “SFSA”) pursuant to Article 20 in the Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on the prospectus to be published when securities are offered to the public or admitted to trading on a regulated market, and repealing Directive 2003/71/EC (the “Prospectus Regulation”). -

Sky Media Vod Intro the Very Best Content – Delivered Wherever, Whenever

Sky Media VoD intro The very best content – delivered wherever, whenever Delivered wherever, whenever Sky Go The way viewers are consuming TV is rapidly changing. At Sky, we Sky Go is Sky’s service that allows users to view content on a are proudly placed at the forefront of this transition, offering our variety of devices including desktop, mobile and tablet customers the ultimate in flexible, fluid viewing. Users stream content from the Sky Go website or app. Viewing has increased rapidly over the past 5 years coinciding with the Whether it be downloading a movie in the living room on the set rise of tablets and smartphones top box, or watching a boxset on an iPad in the park, Sky offers customers the very best content whenever and wherever they Sky Go’s VoD adload is low, and ads are clickable/trackable are. One preroll break and midroll break is the maximum number of breaks on Sky Go content. Each break is restricted to a maximum There are two consumer services, ‘Sky Go’ and ‘On Demand’ of 2 ads so there is very low clutter. In movies there is no midroll. delivering across four strands of content: • Catchup Sky Go Linear allows advertisers to target live viewing too! • Movies The Sky Go Linear platform dynamically overlays the linear • Boxsets transmission with bespoke, targeted ads. This includes channels • Sports from Sky Atlantic to Sky Sports F1 Crucially, movies and boxsets are the biggest drivers of VOD on Sky. This content is incremental to linear viewing and captures viewers at their most engaged, “lean forward” moments. -

The History of the Development of British Satellite Broadcasting Policy, 1977-1992

THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF BRITISH SATELLITE BROADCASTING POLICY, 1977-1992 Windsor John Holden —......., Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds, Institute of Communications Studies July, 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others ABSTRACT This thesis traces the development of British satellite broadcasting policy, from the early proposals drawn up by the Home Office following the UK's allocation of five direct broadcast by satellite (DBS) frequencies at the 1977 World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC), through the successive, abortive DBS initiatives of the BBC and the "Club of 21", to the short-lived service provided by British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB). It also details at length the history of Sky Television, an organisation that operated beyond the parameters of existing legislation, which successfully competed (and merged) with BSB, and which shaped the way in which policy was developed. It contends that throughout the 1980s satellite broadcasting policy ceased to drive and became driven, and that the failure of policy-making in this time can be ascribed to conflict on ideological, governmental and organisational levels. Finally, it considers the impact that satellite broadcasting has had upon the British broadcasting structure as a whole. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION 3 British broadcasting policy - a brief history -

How to Use Your V+ Box

IMPorTANT STUFF Keep these details safe. 4-digit PIN Your Customer Account Number Smart Card Serial Number Calling us If you have any questions, just give us a call free from a Virgin Media phone on 150 Not got a Virgin Media phone line? Call 0845 454 1111 Calls to non geographic numbers (they usually start 0845, 0870 etc) cost no more than 10p per minute plus a connection fee of 7p per call. You can check how much it costs to call our team from a fixed line by visiting our website at virginmedia.com/callcosts or check the Help & Info menu from your TV Home Page. Now, put this booklet somewhere safe and have fun enjoying TV. But if you have any questions, just give us a call. HOW TO USE YOUR V+ BOX VMV+0908 1 WELL, HELLO. CONTENTS WELCOME to MEET YouR New V+ REMote ContROL 4 VIRGIN TV It’s easy to use YouR SPeeDY GUIDE to GettING stARteD 6 If you’re itching to find out what your Can’t wait to get up and running? Virgin TV and V+ Box can do, then ChoosING CHAnneLS 10 keep reading. Three easy ways to watch what you want With the help of Cat and Bird, we’ll USING YOUR V+ BOX 12 help you explore your new service. Telly at your beck and call They love telly. Well, we all love telly ReCORDING PROGRAMMes WIth V+ 12 and they know all about it. So let Never miss a thing them show you how things work. -

Your Guide to Youview+ from BT

Keep this guide somewhere safe You might need it from time to time. All Rights Reserved. Your guide to YouView+ from BT Quick start guide inside The Hunger Games: Catching Fire © 2013, Artwork Fire The Hunger Games: Catching & Supplementary Entertainment TM & © 2014 Lions Gate Materials Inc. The Hunger Games: Catching Fire Available now on BT Box Office Top 10 tips Welcome to YouView from BT Once programmed, you can use your YouView remote In Search, you’ll only see suggestions until you press . You’ll soon be able to sit back and enjoy the shows you love. to control your TV. See page 45. If you can’t see what you’re looking for, press to see everything that matches your search. But first things first. To get set up, just follow the few simple steps starting Try these shortcut buttons on your remote: over the page. It’s easy and shouldn’t take more than half an hour. With the YouView mobile app, you can see what’s on Find any programme available on YouView. and set recordings on the move. Then, you can learn all about YouView and how it’ll help you take control Takes you back to where you were or of your TV in ‘Using YouView’ starting on page 21. back a level in the menus. Go to youview.com/mobileapp to find out more. Takes you back to live TV or out of a High definition Freeview channels are separate from Need some help? No problem – give us a call on 0800 111 4567, go to player menu. -

SATURDAY 28TH JULY 06:00 Breakfast 10:00 Saturday Kitchen

SATURDAY 28TH JULY All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:50 The Big Bang Theory 06:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 10:15 The Cars That Made Britain Great 07:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 11:30 Nadiya's Family Favourites 09:25 Saturday Morning with James Martin 11:05 Carnage 08:00 I Dream of Jeannie 12:00 Bargain Hunt 11:20 James Martin's American Adventure 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 08:30 I Dream of Jeannie 13:00 BBC News 11:50 Eat, Shop, Save 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 09:00 I Dream of Jeannie 13:15 Wanted Down Under 12:20 Love Your Garden 13:00 Shortlist 09:30 I Dream of Jeannie 14:00 Money for Nothing 13:20 ITV Lunchtime News 13:05 Modern Family 10:00 I Dream of Jeannie 14:45 Garden Rescue 13:30 ITV Racing: Live from Ascot 13:30 Modern Family 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 15:30 Escape to the Country 16:00 The Chase 13:55 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 16:30 Wedding Day Winners 17:00 WOS Wrestling 14:20 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 17:25 Monsters vs Aliens 14:45 Ashley Banjo's Secret Street Crew 12:00 Hogan's Heroes 18:50 BBC News 15:35 Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast 12:30 Hogan's Heroes 19:00 BBC London News 16:30 Bang on Budget 13:00 Airwolf The latest news, sport and weather from 17:15 Shortlist 14:00 Goodnight Sweetheart London. -

Sky±HD User Guide

Sky±HD User Guide Welcome to our handy guide designed to help you get the most from your Sky±HD box. Whether you need to make sure you’re set up correctly, or simply want to learn more about all the great things your box can do, all the information you need is right here in one place. The information in this user guide applies only to Sky±HD boxes with built-in Wi-Fi®, which can be identified by checking whether there is a WPS button on the front panel (DRX890W and DRX895W models). Welcome to your new Sky±HD box An amazing piece of kit that offers you: • All the functionality • Easy access to On • A choice of over 50 HD • Up to 60 hours of of Sky± Demand with built-in channels, depending HD storage on your Wi-Fi® connectivity on your Sky TV Sky±HD box or up subscription to 350 hours of HD storage if you have a Sky±HD 2TB box Follow this guide to find out more about your Sky±HD box* * All references to the Sky±HD box also apply to the Sky±HD 2TB box, and the product images in this user guide reflect the Sky±HD box. If you have a Sky±HD 2TB box then it will look slightly different but the functionality is the same. Contents Overview page 4 Enjoying Sky Box Office entertainment page 57 Let’s get started page 9 Other services page 61 Watching the TV you love page 18 Get the most from Sky±HD page 64 Pausing and rewinding live TV page 28 Your Sky±HD box connections page 86 Recording with Sky± page 30 Green stuff page 91 Setting reminders for programmes page 41 For your safety page 95 Using your Planner page 42 Troubleshooting page 98 TV On Demand -

Your Youview User Guide

A brighter home for everyone Your YouView user guide 7 of the most popular Sky entertainment channels 7 day catch-up The best players on your TV Sky Sports and Sky Movies with a one month commitment Rent the latest blockbusters Dip in and out of What’s inside? Sky Sports and Sky Movies Main features 5-7 one month at a time YouView Guide 8-13 Browse and search programmes in the YouView Guide 8 Record 10 Extra channels 13 On Demand 14-19 Catch up on your TV 14 The TalkTalk Player 16 Renting films and adding Boosts 18 Your TalkTalk PIN 19 More information 21-27 Parental controls 21 5 channels for £30 a month 11 channels for £15 a month Now included with our Settings 22 Channels 501-505 Channels 530 -540 Sky Movies Boost FAQ’s 24 Troubleshooting 25 To add instantly go to the channel and press OK talktalk.co.uk/tvboost Quick connection 27 *You’ll need to have a minimum broadband speed of 5Mb to add TV Boosts. All information and prices in this guide are correct at time of going to print and subject to change. Get the most from your YouView box Enjoy all this: Main Features Access all your favourite Freeview channels Use your TalkTalk PIN to watch more -WTVTfV[#gcYeb`f[X You’ll need a working TV aerial to get your Freeview Sign up to our great value Boosts for a month at a YouView Guide channels. Your YouView box will automatically tune time – perfect for the school holidays or the sports -bYf[X`b fcbcg_Te^ in to the standard channels including some in HD.