Rates: Ratiocination Or Roulette? James B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

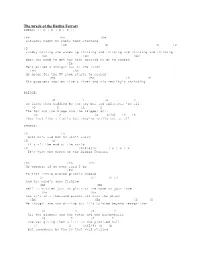

The Wreck of the Barbie Ferrari INTRO: |: D | D | D | D :|

The wreck of the Barbie Ferrari INTRO: |: D | D | D | D :| |Em |Em |Em Saturday night he comes home stinking |Em |D |D |D |D sunday morning she wakes up thinking and thinking and thinking and thinking |Em |Em |Em does she need to get the kids dressed to go to church |Em He's pulled a shotgun out of the lurch |Em |Em He heads for the TV room starts to search |Em |Em |D |D His problems swollen like a river and his reality's shrinking BRIDGE: |G D |A D He finds them huddled by the toy box and splatters 'em all |G D |A D The Ken and the midge and the skipper doll |G D |A (2/4) |B |B They look like a family but they're really not at all CHORUS: |A |A Well he's sad but he ain't sorry |A |G It ain't the end of the world |G |G(2/4)|D | D | D | D It's just the wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |Em |Em |Em He wonders if he ever said I do |Em To that little blonde plastic voodoo |D |D |D |D And his mind's gone fishing |Em |Em Well it started just as plain as the nose on your face |Em |Em now it's in a thousand pieces all over the place |Em |Em |D |D He thought she was driving but it's twisted beyond recognition |G D |A D All the diapers and the tutus and the basketballs |G D |A D she was giving them a lift to the promised mall |G D |A(2/4) |B |B But somewhere by the TV that V-12 stalled |A |A As he loaded the chamber her eyes got starry |A |G It ain't the end of the world |G |G /2/4) |D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A(2/4) |B |B When they get home from church won't they be sorry |A |A He's cornered 'em all on his urban safari |A |G It ain't the end of the world.. -

Barbie® Doll's Friends and Relatives Since 1980

BARBIE® DOLL’S FRIENDS AND RELATIVES SINCE 1980 1980 1987 Beauty Secrets Christie #1295 Jewel Secrets Ken #1719 Kissing Christie #2955 Jewel Secrets Ken (African American) #3232 Scott (Skippers Boyfriend) #1019 Jewel Secrets Whitney #3179 Sport and Shave Ken #1294 Jewel Secrets Skipper #3133 Sun Lovin’ Malibu Christie #7745 Revised Rocker Dana #3158 Sun Lovin’ Malibu P.J. #1187 Revised Rocker Dee Dee #3160 Sun Lovin’ Malibu Skipper #1019 Revised Rocker Derek #3137 Super Teen Skipper #2756 Revised Rocker Diva #3159 Revised Rocker Ken #3131 1981 Golden Dream Christie #3249 1988 Roller Skating Ken #1881 California Dream Christie #4443 California Dream Ken #4441 1982 California Dream Midge #4442 Star Ken #3553 California Dream Teresa #5503 Fashions Jeans Ken #5316 Cheerleader Teen Skipper #5893 Pink and Pretty Christie #3555 Island Fun Christie #4092 Sunsational Malibu Christie #7745 Island Fun Miko #4065 Sunsational Malibu P.J. #1187 Island Fun Skipper #4064 Sunsational Malibu Ken #1088 Island Fun Steven #4093 Sunsational Malibu Ken (African American) #3849 Island Fun Teresa #4117 Sunsational Malibu Skipper #1069 Party Teen Skipper #5899 Western Ken #3600 Perfume Giving Ken #4554 Perfume Giving Ken (African American) #4555 1983 Perfume Giving Whitney #4557 Barbie & Friends Pack #4431 Sensation Becky #4977 Dream Date Ken #4077 Sensation Belinda #4976 Dream Date P.J. #5869 Sensation Bobsy #4967 Horse Lovin’ Ken #3600 Teen Sweetheart Skipper #4855 Horse Lovin’ Skipper #5029 Workout Teen Skipper #3899 Todd (Ken’s Handsome Friend) #4253 Tracy (Barbie’s Beautiful Friend) #4103 1989 Animal Lovin’ Ken #1351 1984 Animal Lovin’ Nikki #1352 Crystal Ken #4898 Beach Blast Christie #3253 Great Shape Ken #7318 Beach Blast Ken #3238 Great Shape Skipper #7414 Beach Blast Miko #3244 Sun Gold Malibu Ken #1088 Beach Blast Skipper #3242 Sun Gold Malibu P.J. -

International Auction Gallery 1530 S

International Auction Gallery 1530 S. Harris Ct., Anaheim, CA 92806 714-935-9294 May 17, 2021 Auction Catalog Prev. @ Sun. (5/16) 10am-4pm & Mon. 10am-2pm, Sale Starts 2pm Lot # Item description L. Est. H Est. start 16 Disney collectible and more $30 $90 $10 17 Lot of misc. Disney items $30 $90 $10 18 Lot of misc. Disney items $30 $90 $10 19 Lot of miniatures $30 $90 $10 20 Lot of miniatures $30 $90 $10 21 1960 Ken doll with wardrobe $60 $80 $20 22 Marl and Barbie, appear to be new in box $30 $50 $10 23 1962 Midge doll with pink dress $80 $100 $20 24 1965 Midge doll with swimming suit, made in Japan $80 $150 $20 25 Two 1962 Midge dolls with molded hair $80 $100 $20 26 1962 Midge doll with straight leg, head need to be rejoint $10 $50 $5 27 1964 G.I. Joe navy sailor doll $80 $150 $20 28 Over 15 Ken doll 60's zebra bathing/ swimming suit $30 $90 $10 29 Lot of 60's Ken doll clothing $30 $90 $10 30 Lot of 60's Ken doll clothing $30 $90 $10 31 Lot of 60's Ken doll clothing $30 $90 $10 32 Lot of 60's Ken/ Barbie/ skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 33 Lot of 60's Barbie/ Skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 34 Lot of 60's Barbie/ Skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 35 Lot of 60's Barbie/ Skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 36 Lot of 60's Barbie/ Skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 36A Lot of 60's Barbie/ Skipper clothing $30 $90 $10 37 1960 Ken doll with box and a Ken doll $30 $90 $10 38 1966 Barbie (Japan), 1966 Barbie (Korea, missing arm), and a miniature Barbie with $30 $90 $10 Barbie box 39 Lot of 60's misc. -

Barbie As Cultural Compass

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Sociology Student Scholarship Sociology & Anthropology Department 5-2017 Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll Hannah Tulinski College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://crossworks.holycross.edu/soc_student_scholarship Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Tulinski, Hannah, "Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll" (2017). Sociology Student Scholarship. 1. http://crossworks.holycross.edu/soc_student_scholarship/1 This Department Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology & Anthropology Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. “Barbie As Cultural Compass: Embodiment, Representation, and Resistance Surrounding the World’s Most Iconized Doll” Hannah Rose Tulinski Department of Sociology & Anthropology College of the Holy Cross May 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Chapter 1: Barbie™ 5 Chapter 2: Cultural Objects and the Meaning of Representation 30 Chapter 3: Locating Culture in Discourse 45 Chapter 4: Barbie’s World is Our World 51 Chapter 5: Competing Directions of Cultural Production 74 Chapter 6: Role Threat 89 Role Transformation 104 Discussion 113 References 116 Appendix I: Popular Discourse 122 Appendix II: Scholarly Discourse 129 2 Acknowledgements First, thank you to Professor Selina Gallo-Cruz, who not only advised this thesis project but also who has mentored me throughout my development at College of the Holy Cross. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

1 Below Is a Comprehensive List of All the Lines Hello Barbie Says As O

Below is a comprehensive list of all the lines Hello Barbie says as of November 17, 2015. We are consistently updating and enhancing the product’s vocabulary and will update the lines on this site periodically to reflect any changes. OK, sooooo..... I love hanging out with you! (SIGH) Wow... there's so much we can talk about... I've got a question for you... Oh! I know what we can talk about... Oh, I know what we can do now... Speaking of things you want to be when you grow up... You know what I want to talk about? FRIENDS! So, let's talk friends! Ooh, why don't we talk about friends! Hey... let's talk about friends for a bit! I'm the most myself when I'm around my friends, just playing games and imagining what we'll be when we grow up! You know, I really appreciate my friends who have a completely unique sense of style... like you! You know, on those days where waking up for school is hard, I just think about how much fun it'll be to see my friends. ©2015 Mattel. All Rights Reserved. Version 2 1 You know, talking about all the fun things we do is making me think about who we could do them with ... friends! So we've been talking about family, let's talk about the other people in our lives that mean a lot to us ...like our friends! I bet someone who's a friend to animals knows a thing or two about being a friend to people. -

Sunday Dollar Auction - Collectibles!

09/28/21 07:19:57 Sunday Dollar Auction - Collectibles! Auction Opens: Mon, Aug 12 7:00am PT Auction Closes: Sun, Aug 18 6:00pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0520 Patrol car BC0117 Tootie toys hitch up 0521 Jeep BC0118 Tootsie toy U.S. Army 0522 Highway patrol BC0119 Combat Patrol 0523 Chips BC0120 Hitch-ups 0524 Patrol car BC0121 US Army hitch-ups 0525 Color splash BC0122 Tootsie-toys hitch ups 0526 Match box BC0123 US Army hitch ups 0527 Big Farm tractor BC0124 Dare Devil die cast 0528 Harley Davidson BC0125 Tootsie hitch-ups AM0100 De Luxe Home Decorators Silverware set BC0126 Tootsie hitch ups plated/ full set very nice in case BC0127 US Army hitch ups AM0101 Silverware, various pieces BC0128 US Army Hitch ups AM0102 Jewelry box full of jewelry BC0129 Fall guy stuntman assoc. GM pick up AM0103 Showcase full of various jewelry BC0130 Die Cast Metal street machine BC0100 Ertl Fall Guy die cast metal truck GM pickup BC0131 US Army armored car BC0101 Midgetoy Daredevil trucks BC0132 US Army armored car BC0102 Ertl Die cast metal replica Richard Petty BC0133 Super wheels tractor die cast metal 43/superstock car BC0134 Cale Yarorough superstock race car 27 BC0103 Die Cast Metal Mini Cars BC0135 US Army armored car BC0104 Marz Karz quality die cast BC0136 Stunt cycle friction power BC0105 Karz Karz Motorized Quality die cast trans am BC0137 Quality die cast BC0106 Midge toy Dare Devil die cast metal BC0138 US Army armored car BC0107 Fall Guy stuntman assoc. quality die cast metal GM pick up BC0139 US Army armored car BC0108 midge toy Dare Devil die cast metal BC0140 Marz Karz quality die cast BC0109 Die cast metal truck with trailer and motorcycles BC0141 US Army armored car BC0110 US Army die cast metal BC0142 US Army Armored car BC0111 Tootsie toy U.S. -

Barbie-Q 1991

SANIRA CISNER0S 1). 1951. American Poet and /ittwn writer .Sandra cisneros grew up in (iiicagn. the only daughter among the seven children of a Jiexicaw horn father and Wextcan— American mother. A s a child she inoi’edf)’equent/v between the I tilted States aiid ‘kkvico. cjsending perwds in her father hometown of itlexico (ity. As he recalls humoisusly in one poem. her father envisioned professional careers f/sr all his children, pointing ins sons toward medicine and law hut deciding that she would he ideal as 1 It/er isbn ii rathir yil “h ins nt/id / olo/a ( ,ui mity in ( hi igo and is a ,rirl nate oft/se University of Iowa Writers W/srkshop. where she has said that she first realized that her unique Incuitural csperiemes could “fill a litersiry i’o,d. (Js,iero/s first book was Bad liovs ( /980), a poetry chaphook fom Manc’o Publications, a small pub/is/icr specializing in (J’uwno writers, and she has since published two other books of poetry, Mv \X/ikd, Wicked \X/avs (I98) and I \Voman s1994), both of which vp/ore themes of feminism. stt1nidiit and cultural identity Her books of fiction include I he I loose on Mango Street (1984), which received the Be//ire Columbus American Book Au’ard and broug’ht her to the atten— non of critics and a wider audience. and Woman Hollering ( :k (1991). The House on Mango Street employs an experimental form. consistznçi ofhriefsketches and longer stories which use a central protagonist. I/se compression, rhythms, and imagery ofshort pieces like “Barbie() “are perhaps as close 10 the spirit ofrose po etry as tojiction. -

“Barbie's Little Sister” How Terrible It Would Be to Be Barbie's Little Sister, Suspended in Perpetual Pre-Adolescence Whil

“Barbie's Little Sister” How terrible it would be to be Barbie's little sister, suspended in perpetual pre-adolescence while Barbie, hair flying behind her in a tousled blonde mane, dashed from adventure to adventure, ready for space travel or calf roping or roller disco in campy, flashy clothes that defied good taste and reason. Stuck with the awful nickname Skipper, Barbie's little sis never got out much, a mere boarder in Barbie's three-story hot-pink Dream House, too young to wear the thousands of outfits stashed in the bedroom closets: purple beaded Armani evening gowns, knit sweater dresses by Donna Karan, specially commissioned tennis togs sewn personally by Oleg Cassini. Skipper had to buy stuff off the rack at K-Mart, condemned to wear floral sunsuits with Peter Pan collars. Unlike her bosomy sister, Skipper had no chest for the boys to ogle, until some bright toy maker gave us Growing Up Skipper: with a twist of her right arm, she grew taller, breasts sprouting where there once were none, a thick rubber band inside her © 1997 Allison Joseph from In Every Seam pushing her chest up and out until the band snapped and Skipper was stuck at age fifteen, never the same again. For consolation, she turned to Barbie's black friend Christie- who was just figuring out all the fuss about equal rights- and Barbie's best pal Midge, who was tired of hearing about spats with Ken, knowing he was cheating on America's sweetheart with every new celebrity doll on the market- Brooke Shields, Cher, Dorothy Hamill. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of Education TRACING PUERTO RICAN GIRLHOODS: an INTERGENERATIONAL

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Education TRACING PUERTO RICAN GIRLHOODS: AN INTERGENERATIONAL STUDY OF INTERACTIONS WITH BARBIE AND HER INFLUENCE ON FEMALE IDENTITIES A Dissertation in Curriculum and Instruction by Emily R. Aguiló-Pérez © 2016 Emily R. Aguiló-Pérez Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 The dissertation of Emily R. Aguiló-Pérez was reviewed and approved* by the following: Jacqueline Reid-Walsh Associate Professor of Education and Women’s Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Daniel Hade Associate Professor of Education Christine Marmé Thompson Professor of Art Education Courtney D. Morris Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Women’s Studies William Carlsen Professor of Education Director of Graduate and Undergraduate Studies, Curriculum and Instruction *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Since her creation in 1959, Barbie has become an icon of femininity and an important artifact in girls’ cultures. The doll has become a great part of children’s lives either through her presence or her absence in their play experiences. Moreover, the feelings and memories she evokes can provide insights to girls’ lived experiences in relation to a number of topics. As a result, Barbie becomes an important artifact of girlhood and an excellent site of interrogation about girlhood. While a large amount of research has examined Barbie’s role in girls’ lives, the scholarship has not included the experiences of Puerto Rican girls. This study examines the experiences of a group of multigenerational Puerto Rican women and girls who interacted with Barbie dolls during their childhood and the social and cultural implications these experiences may have on their lives in the present. -

Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics by Tim Rice

MUSIC BY ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER LYRICSLYRICS BY BY TIM TIM RICE RICE IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE REALLY USEFUL GROUP LIMITED PRODUCTION BY REGENT'S PARK THEATRE, LONDON JCS_ProgramCover.indd 1 3/28/2018 10:29:44 AM THE BELOVED BROADWAY MUSICAL COMES TO LYRIC IN SPRING BERNSTEIN SONDHEIM LYRIC PREMIERE NEW COPRODUCTION MAY JUNE , LYRICOPERA.ORG .. DIRECTOR SET DESIGNER WEST SIDE STORY Based on a conception of Jerome Robbins Book by Arthur Laurents Music by Leonard Bernstein Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Francesca Zambello Peter J. Davison A coproduction of Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, and Glimmerglass Festival. Original production directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins. COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER Lyric Opera premiere of Bernstein’s West Side Story generously made possible by Lead Sponsor The Negaunee Foundation and cosponsors an Jessica Jahn Mark McCullough Anonymous Donor, Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin, Robert S. and Susan E. Morrison, Mr. and Mrs. William C. Vance, and Northern Trust. LYRIC OPERA OF CHICAGO Table of Contents JOHAN PERSSON IN THIS ISSUE Jesus Christ Superstar – pp. 19-35 6 From the General Director 21 Cast 47 Look to the Future and Chairman 22 Synopsis/Musical Numbers/Orchestra 48 Major Contributors – Special Events 8 Board of Directors 23 Artist Profiles and Project Support 10 Women’s Board/Guild Board/Chapters’ Executive Board/Young Professionals/ 30 Musical Notes 49 Lyric Unlimited Contributors Ryan Opera Center Board 34 Director’s Note 50 Commemorative Gifts 12 Administration/Administrative Staff/ 35 After the Curtain Falls Production and Technical Staff 52 Ryan Opera Center Alumni 36 Patron Salute 14 The Thrill of It All: Lyric’s Around the World 2018/19 Season 37 Aria Society 53 Ryan Opera Center Contributors 19 Tonight’s Performance 46 Breaking New Ground 54 Planned Giving: The Overture Society ALL ABOUT NEXT SEASON pp. -

Vintage Barbies Toys & Collectible Auction

10/03/21 09:30:13 Vintage Barbies Toys & Collectible Auction (18) Auction Opens: Fri, Jul 16 6:57pm PT Auction Closes: Thu, Jul 22 6:07pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Ruby Red Cut Crystal Glass Set 0031 Vintage 1964 Skipper Straight Leg Brunette 0002 Ruby Red Cut Crystal Glassware Set & Bowl Doll 0003 Fostoria Crystal Ruby Red 2pc 0032 Vintage Malibu Blonde Skipper Bendable Leg Doll 0004 Vintage Iridescent Horizon Blue Chicken Hen on Nest Covered Candy Dish 0033 Vintage 1966 Mattel Twist & Turn Barbie 2pc 0005 Vintage Blue Carnival Glass Pitcher 0034 Vintage Brunette American Girl & Red Head Bubble Cut Barbie Heads 0006 2pc Harvest Grape Carnival Glass Candy Jars 0035 Vintage Barbie Color & Curl Magic Hair Color 0007 Iridescent Marigold Carnival Glass Bowl Set 0008 Vintage Frosted Ruffle Hobnail Bowl 0036 Vintage 1961 Ken Doll Case & Clothes 0009 Vintage Pink Depression Glass Bowl 0037 Vintage 1962 Barbie Doll Case & Clothes 0010 Hand Painted Japan Teapot Set 0038 Vintage Midge 1963 Doll Carrying Case with 0011 Tea Cup & Saucer Lot Barbie Clothes 0012 Skytone Homer Laughlin Stardust Teapot 0039 Vintage Barbie Doll Carrying Case & Barbie Pitcher Set Clothes 0013 Vintage Decorative Floral Porcelain Lot 0040 Vintage 1964 Skipper Carrying Case & Skipper 0014 Vintage Hull Art Ceramic Pottery Vase Clothes 0015 Murano Glass Rooster 0041 Vintage 1963 Pink Barbie & Midge Doll Case 0016 Vintage 4pc Figurines Vase 0042 Vintage Pink Metal Carrying Case Filled with Barbie Accessories 0017 Jan Hagara Figurines & More 0043 Vintage 1960s Barbie Clothes