Recreational Activity and Interactions with Birds Within the Sssis on the North-West Coast of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11E5: Dubmill Point to Silloth

Cumbria Coastal Strategy Technical Appraisal Report for Policy Area 11e5 Dubmill Point to Silloth (Technical report by Jacobs) CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E5 DUBMILL POINT TO SILLOTH Policy area: 11e5 Dubmill Point to Silloth Figure 1 Sub Cell 11e St Bees Head to Scottish Border Location Plan of policy units. Baseline mapping © Ordnance Survey: licence number 100026791. 1 CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E5 DUBMILL POINT TO SILLOTH 1 Introduction 1.1 Location and site description Policy units: 11e5.1 Dubmill Point to Silloth (priority unit) Responsibilities: Allerdale Borough Council Cumbria County Council United Utilities Location: This unit lies between the defended headland of Dubmill Point and Silloth Harbour to the north. Site overview: The shoreline is mainly low lying, characterised by a wide mud, sand and shingle foreshore, fronting low lying till cliffs and two belts of dunes; at Mawbray and at Silloth. The lower wide sandy foreshore is interspersed by numerous scars, including Dubmill Scar, Catherinehole Scar, Lowhagstock Scar, Lee Scar, Beck Scar and Stinking Crag. These scars are locally important for wave dissipation and influence shoreline retreat. The behaviour of this shoreline is strongly influenced by the Solway Firth, as the frontage lies at the estuary’s lower reaches. Over the long term, the foreshore has eroded across the entire frontage due to the shoreward movement of the Solway Firth eastern channel (Swatchway), which has caused narrowing of the intertidal sand area and increased shoreline exposure to tidal energy. The Swatchway currently lies closer to the shoreline towards the north of the frontage. There is a northward drift of sediment, but the southern arm of Silloth Harbour intercepts this movement, which helps stabilise the beach along this section. -

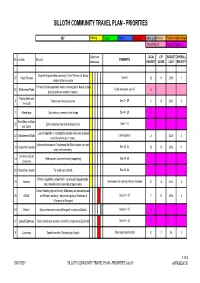

Item 09 Appendix Silloth

SILLOTH COMMUNITY TRAVEL PLAN - PRIORITIES KEY Walking Cycling Public T Car/Safety Other (n/a) Funded Transfer to other budget Linked Request Duplicate Requests Objectives LOCAL LTP BUDGET OVERALL NoLocation Request COMMENTS addressed PRIORITY SCORE COST PRIORITY Request for pedestrian crossing at Hylton Terrace for School 27 Hylton Terrace See 50 20 11 £15k 1 children & library people Primary School desperately needs crossing patrol. Needs to be a 50 Skinburness Road To be assessed - see 27 4 priority before an accident happens. Playing fields and 8 Pedestrian crossing required See 7 + 29 3 12 £12k 2 The Croft 7 After bridge Drop kerb on pavement after bridge See 8 + 29 32 Post Office and Spar 29 Zebra crossings from and to playing field. See 7 + 8 5 and Crofts Lack of footpaths. If no footpaths possible some sort of speed 32 Blitterlees to Silloth Land required 2 £20k 3 restrictions to be put in place. Continued from oppsite Tanglewood the Silloth people can walk 24 Footpath to Cemetery See 28, 44 13 12 £15k 4 safely to the cemetery. Cemetery at East 44 Path required (accidents nearly happening) See 24, 28 Causeway 28 Footpath to Cemetery To avoid early arrivals See 24, 44 Difficult negotiating wheelchairs - not enough dropped kerbs - 18 General Enforcement of existing Police & Allerdale 21 13 £10k 5 also motorists park across the dropped kerbs. Current flooding signs at Allonby & Mawbray are ignored becaus 26 B5300 are left open too long + advanced signing at Greenrow & See 33 + 47 7 9 £16k 6 Ellengrove at Maryport 33 Dubmill Sign to show when road to Maryport is closed at Dubmill. -

North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2

North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 North West & North Wales Coastal Group North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan SMP2 Main SMP2 Document North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Approved by 14 th September 1 0 1st Working Draft – for PMB Review A Parsons 2009 1st October 1 1 Consultation Draft A Parsons 2009 2 0 Draft Final 9th July 2010 A Parsons Minor edits for QRG comments of 3 rd 9th September 2 1 A Parsons August 2010 2010 Minor amendment in Section 2.6 and 12 th November 2 2 A Parsons Table 3 2010 18 th February 3 0 Final A Parsons 2011 Halcrow Group Limited Burderop Park, Swindon, Wiltshire SN4 0QD Tel +44 (0)1793 812479 Fax +44 (0)1793 812089 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client, Blackpool Council, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2011 North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................2 1.1 NORTH WEST ENGLAND AND NORTH WALES SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 ......................................... 2 1.2 THE ROLE OF THE NORTH WEST ENGLAND AND NORTH WALES SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2......... 3 1.3 THE OBJECTIVES OF THE SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 ................................................................................. 5 1.4 SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 REPORT STRUCTURE ....................................................................................... -

Dubmill Point to Silloth Harbour Management Area Summary 2013 Allerdale Borough Council

Dubmill Point to Silloth Harbour Management Area Summary 2013 Allerdale Borough Council DUBMILL POINT TO SILLOTH HARBOUR Baseline Information Start co-ordinate: 307650, 545742 Finish co-ordinate: 310417, 553559 Total length: 8.3km Defended length: 0.5km Gabions: 0.2km Rock Armour: 0.3km Sand Dunes/Cliff: 7.8km Environmental designations: Monitoring carried out: SSSI 18 beach profiles SAC Topographic survey (dunes south of harbour) SPA Coastal defence inspection Ramsar AONB Site overview: The frontage between Dubmill Point and Silloth harbour is a low-lying, natural frontage (Coastal Engineering UK, 2010), apart from on the north side of the point, as the shoreline moves easterly and the highway moves inland, where the heavy concrete defences give way to a short length of less robust gabion defences which then interface to the natural shoreline. Across the natural section of frontage a wide sandy lower foreshore, interspersed with boulder beds or scars, and shingle upper beach front an extensive dune system. At Mawbray and Beckfoot two becks discharge onto the foreshore. The northerly drift of shingle has pushed the discharge point of these two becks further north. New rock armour defences were planned to be constructed by Cumbria CC between Mawbray and Beckfoot in 2013, to protect the shoreline from erosion and prevent loss of the B5300 coastal road. The Current (SMP2) Policy: Dubmill Point to Silloth: Managed Realignment in the short term (0-20yrs), Managed Realignment in medium term (20-50yrs) and long term (50-100yrs). The -

English/French

World Heritage 36 COM WHC-12/36.COM/8D Paris, 1 June 2012 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-sixth Session Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 24 June – 6 July 2012 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8D: Clarifications of property boundaries and areas by States Parties in response to the Retrospective Inventory SUMMARY This document refers to the results of the Retrospective Inventory of nomination files of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. To date, seventy States Parties have responded to the letters sent following the review of the individual files, in order to clarify the original intention of their nominations (or to submit appropriate cartographic documentation) for two hundred fifty-three World Heritage properties. This document presents fifty-five boundary clarifications received from twenty-five States Parties, as an answer to the Retrospective Inventory. Draft Decision: 36 COM 8D, see Point IV I. The Retrospective Inventory 1. The Retrospective Inventory, an in-depth examination of the Nomination dossiers available at the World Heritage Centre, ICOMOS and IUCN, was initiated in 2004, in parallel with the launching of the Periodic Reporting exercise in Europe, involving European properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. The same year, the Retrospective Inventory was endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its 7th extraordinary session (UNESCO, 2004; see Decision 7 EXT.COM 7.1). -

Solway Basin Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 6: Solway Basin Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 6: Solway Basin Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2020-25 1 A74 (M)

Solway Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2020 -25 Consultation draft www.solwaycoastaonb.org.uk Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2020-25 1 A74 (M) T L A N D A6071 S C O A75 retna 45 sk E Annan r e v i R astrggs Rockcliffe A7 Marsh Bowness-on-Solway Hadrian’s Wall (course of) Port Carlsle •Rockcliffe arsh gh M lasson ur Solway Wetlands Centre Glasson B Moss 44 Bowness Common and Burg-by- Reserve Sans M6 Campfield Marsh Reserves rumburg Beaumont Hadrian’s Wall A7 (course of) • River Ede Hadrian’s(course Wall of) H Antorn Drumburgh Boustead Hill n R T Carurnock Moss Monkll F I Reserve B5307 er Eden Y Angerton rkbamton Riv Grune Point h Finglandrigg A rs A69 a rkbre Wood M Thurstonfield W n B5307 Reserve 43 Sknburness o L t Lough w Skinburness e Newton Arlos R • Orton Moss O i Carlisl N v ttle Bamton Marsh e Reserve S r W reat Orton Solway Discovery Calvo a m Centre Marsh Wedholme p Watchtree o o Flow l Reserve A6 B5299 Lees Scar Lighthouse Sllot Reserve A595 42 B5302 Martin Tarn ew I A ald B R r C Holme Cultram Abbey M e B5300 iv U R er Wave C • Riv r Abbeytown ursby alston Beckoot gton B5302 B5299 B5305 Tarns A595 Dub B5304 Mawbray Dubmill Point A596 B5301 B5300 Motorway Solway Coast estnewton Area o Outstanng Natural Beauty A roa rmary route Allonby A roa man roa Bult-u area Ste o natural or storcal nterest Asatra B5299 B roa Nature resere Mnor roa Mars A595 B5300 B5301 n al lne staton stor centre lle E er iv R arans all lle ste Crosscanonby course o ertage ste A596 0 1 2 klometres 0 1 2 mles Parkng A594 Front cover image: Sunset over Dubmill Maryort Ministerial Foreword To be added in final version www.solwaycoastaonb.org.uk Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2020-25 1 Chair’s Foreword To be added in final version 2 Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2020-25 www.solwaycoastaonb.org.uk Our 2030 vision Contents It is 2030. -

Holme Low Parish Council Minutes of a Meeting Held on Monday 12 August 2014 at 7.30Pm at Silloth Community Hall

Holme Low Parish Council Minutes of a meeting held on Monday 12 August 2014 at 7.30pm at Silloth Community Hall Present Cllr. J. Graham (JG) – Chairman Councillors M. Wright (MW) A. Sowden (AS) N. Dainton (ND) D. Findlay (DF) M. Pearson (MP) Also present: Wendy Jameson – Town Clerk (WEJ), Barbara Hepburn – Holme St Cuthbert’s and Cllr. Tony Markley – Cumbria County Council. 1. Apologies None 2. Declarations of Interest None 3. Exclusion of Press & Public None 4. Minutes The minutes of the meeting held on 13 May 2014 were approved by the Parish Council and signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. Matters Arising The Clerk received a call from Mr Storr in relation to his trailer which he said was not parked on the Highway but the problem was that where it was parked was obstructing the view of motorists around the corner. 6. Police Report Police Newsletter was received by email. 7. Holme St Cuthbert’s Community Group Barbara Hepburn attended the meeting and gave a report about the activities of the Holme St Cuthbert’s Community Group. The group has raised enough money to purchase a defibrillator which is to be sited in the school. Holme St Cuthbert’s is a scattered parish and it was hoped the Community group would bring people together and create a community spirit. They have had a Pie & Pea supper, a raffle and a poetry workshop, with a walk and orienteering organised for September. The purpose of the group is to support people in the Parish, to bring people together and facilitate things. -

April 2019 in Holme St Cuthbert Parish Hall

Clerk: Linda J Housby Tel: 016973 20839 Email: [email protected] Web: www.holmestcuthbertparish.com MINUTES OF THE MEETING Minutes of a meeting of Holme St Cuthbert Parish Council held on: Wednesday 10 April 2019 in Holme St Cuthbert Parish Hall Present: Mrs M Knoery chairman, Mr R Armstrong vice-chairman, Mr J Molyneux, Mrs L Stevens, Mrs S Donachy, Mr S Routledge, Mr P Gibbons and Mrs L J Housby clerk Members of the Public: Councillors Markley and Lister, Ms Amber Sykes CCC Highways, Mr Rickie Crawford CCC Highways Engineering and 40 parishioners Apologies: Mrs MK welcomed everyone to the meeting AS & RC gave out handouts showing aerial photos of the erosion and explained they have been overly cautious to close the B5300 Dubmill to Mawbray, realised it has as had big impact on surrounding areas There are two parts to too this work original area 1 erosion got worse in area 2 SSSI Needed specialist site permission from Natural England, MMO (for working on the beach) still awaiting European Species Licence (Natterjack Toads) cannot start work without consent (if start work without it there would be large fines and imprisonment) as soon as licence granted work will start, when tides allow, leaflet explains about the rock armour 1 in 2 slope dug into beach at bottom stones will interlock, when sea comes up will naturally drain, this is a temporary fix The leaflets explain work/costs/hope to not damage SSSI site as little as possible Trying to fast track last licence, pressure from CCC/Local Councillors to start as soon as possible, -

Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2015 – 2020 “A Shared Responsibility for a Very Special Place”

Solway Coast AONB Management Plan 2015 – 2020 “A shared responsibility for a very special place” Public and Stakeholder Consultation Draft May 2014 Written and compiled by: Brian Irving and Rose Wolfe Ministerial Foreword Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) are some of our finest landscapes. They are cherished by residents and visitors alike and allow millions of people from all walks of life to understand and connect with nature. I am pleased to see that this management plan demonstrates how AONB Partnerships can continue to protect these precious environments despite the significant challenges they face. With a changing climate, the increasing demands of a growing population and in difficult economic times, I believe AONBs represent just the sort of community driven, collaborative approach needed to ensure our natural environment is maintained for generations to come. AONB Partnerships have been the architects of a landscape-scale approach to land management. This approach is a key feature of the Government’s Natural Environment White Paper and emphasises the need to manage ecosystems in an integrated fashion, linking goals on wildlife, water, soil and landscape, and working at a scale that respects natural systems. This management plan also makes the important connection between people and nature. I am pleased to hear that local communities have been central to the development of the plan, and will be at the heart of its delivery. From volunteers on nature conservation projects, to businesses working to promote sustainable tourism, it’s great to hear of the enthusiasm and commitment of the local people who hold their AONBs so dear. -

Maryport to Dubmill Point

Cumbria Coastal Strategy Technical Appraisal Report for Policy Area 11e4 Maryport to Dubmill Point (Technical report by Jacobs) CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E4 MARYPORT TO DUBMILL POINT Policy area: 11e4 Maryport to Dubmill Point Figure 1 Sub-Cell 11e St Bees Head to Scottish Border Location Plan of policy units. Baseline mapping © Ordnance Survey: licence number 100026791. 1 CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E4 MARYPORT TO DUBMILL POINT 1 Introduction 1.1 Location and site description Policy units: 11e4.1 Maryport Harbour to Roman Fort (Maryport) 11e4.2 Roman Fort to Bank End (Maryport Promenade) 11e4.3 Maryport Golf Course to Allonby (priority unit) 11e4.4 Allonby (priority unit) 11e4.5 Allonby to Seacroft Farm (priority unit) 11e4.6 Seacroft Farm to Dubmill Point (priority unit) Responsibilities: Allerdale Borough Council Cumbria County Council Private defence owners Location: This unit runs from Marport Harbour to Dubmill Point and encompasses Allonby Bay, which has developed due to greater erosion of the less resistant geology within Allonby Bay compared to the headlands at either end. At Dubmill Point, itself, the artificial reinforcing of the promontory to protect local infrastructure has maintained its role as a strategic control point. Site Overview: Maryport Promenade protects a section of resistant relict cliffs which extend from Maryport to Bank End. North of this point the cliffs lower before rising again to around 15 m where the relict cliffs terminate at Swarthy Hill. Between Swarthy Hill and the reinforced low headland at Dubmill Point, the cliffs are replaced by low lying land, interspersed by high sand dune ridges and shingle ridges, fronted by a continuing sand and shingle foreshore which widens considerably, north of Allonby. -

Allonby Bay Management Area Summary 2015 Allerdale Borough Council

Allonby Bay Management Area Summary 2015 Allerdale Borough Council ALLONBY BAY (MARYPORT TO DUBMILL POINT) Baseline Information Start co-ordinate: 302966, 536857 Finish co-ordinate: 307650, 545742 Total length: 10.9km Defended length: 4.8km Sea Wall: 3.6km Rubble defence: 1.2km Natural cliff: 6.1km Environmental designations: Monitoring carried out: AONB 22 beach profiles Coastal defence inspection Site overview: The section of frontage lies within the embayment between Maryport harbour and Dubmill Point. Maryport is built on a sandstone outcrop with high cliffs rising above the shoreline. The history of Maryport harbour begins in the early 18th century when the first exports of coal were made. In 1836 a tidal dock was created. The Elizabeth Dock and Senhouse Dock were added in 1857 and 1884 respectively. The shoreline between Maryport and Bank End is defended by a vertical sea wall, which is founded along parts of its length on underlying sandstone bedrock. The defences were originally built in the 1930s and reduced erosion but also led to beach levels dropping. The Maryport Golf Course frontage is defended by an informal revetment of tipped material comprising brick hardcore, broken concrete etc, which dates from the 1990s. North of Bank End the cliffs which back the shoreline lower in height before rising to 15m at Swarthy Hill. Between Swarthy Hill and Dubmill Point low lying land is interspersed by sand dunes and shingle ridges providing protection to the highway and the village of Allonby. North of Oldkiln, across Dubmill Point, the shoreline has been artificially hardened to provide protection to the public highway, which runs adjacent to the coast here.