Curriculum 2000: Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KS5 Transition Information Thinking Beyond Bonus Pastor: a Student Guide

Name: ____________________ KS5 Transition Information Thinking Beyond Bonus Pastor: A Student Guide Ms Hill – Leader of CEIAG and KS5 Transition [email protected] Today you have taken part in a KS5 Transition Meeting which I hope that you found interesting and insightful. The aim of this meeting was to get you thinking beyond Bonus Pastor. You will receive a copy of the Personal Action Plan that we created together in the meeting. Keep this together with the attached information, and use it to help guide you through the KS5 Transition process. If you or your parents/carers have any questions at any time, please email me – no question is a silly question! Qualifications Explained – What Can I Apply For? You are currently studying for GCSEs which are Level 1 or 2 qualifications, depending on what grades you achieve at the end of Year 11. Generally speaking: if you are forecast to achieve GCSEs at grades 1 - 4 then you can apply for Level 1 or 2 BTEC courses or an intermediate level apprenticeship. Once you have completed this you can progress to Level 3 courses. if you are forecast to achieve GCSEs at grades 4 or above then you can apply to study A Levels, Level 3 BTEC courses, or intermediate level or advanced level apprenticeships. (Most A Level courses will require you to have at least a grade 5 or 6 in the subjects you wish to study.) However if you are applying for a vocational trade-based course such as Hair and Beauty, Motor Vehicle Mechanics or Electrical Installation, all courses start at Level 1 and then progress up to Level 2 and 3 courses. -

Prospectus 2021

Driffield School 2021 & Sixth Form Prospectus Believe • Achieve Welcome to Driffield School & Sixth Form Since taking up post as Executive Principal of Driffield School & Sixth Form in April 2018, I have been delighted by the friendly and supportive nature of the students, parents and staff. The school has enormous potential and I look forward to welcoming your child to the school at such an exciting time. At Driffield School & Sixth Form, we recognise that choosing a school for your child is a crucial decision and we take our responsibilities very seriously when parents entrust their child’s education and care to us. We will do everything we can to ensure that every individual child receives the care, support and guidance they need to thrive. We are ambitious for each one of our students, sharing in their successes and seeing them leave us after seven years, able to fulfil their dreams and aspirations. We will do our utmost to help them succeed and we have high standards and expectations of all our students. All our students benefit from a broad and balanced curriculum that ensures that they experience exciting opportunities both within and outside the classroom. Our curriculum is designed to enable our students to make good progress towards their academic targets and to provide remarkable experiences that will stay with them for a lifetime. We very much hope that the information in this prospectus gives you a flavour of what we have to offer. More details are available on the school website, through regular newsletters and school round-ups. -

Make It Happen Prospectus 2020/2021 Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus

MAKE IT HAPPEN PROSPECTUS 2020/2021 WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS EXTENDED PROJECT QUALIFICATION WELCOME COURSE Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) 34 TO WYKE ENGLISH INDEX English Literature 35 “WYKE OFFERS A TRUE ‘SIXTH FORM’ EXPERIENCE WITH English Language 35 HIGH QUALITY SPECIALIST TEACHING, A UNIVERSITY STYLE BUSINESS and FINANCE MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES CAMPUS, A CULTURE THAT FOSTERS INDEPENDENCE, Accounting 22 German 36 ENCOURAGING STUDENTS TO BE THEMSELVES. Economics 22 French 37 As the largest A Level provider in Hull and East Riding, the Spanish 37 statistics are straightforward; students do very well at Wyke Business A Level 23 Sixth Form College, with our results justifying the position in Business BTEC 23 HUMANITIES the top 15% of all Sixth Form providers nationally. VISUAL ARTS History 38 In 2019, our pass rate percentage at A Level was 99.7%, with Government and Politics 38 the BTEC pass rate at 100%. This includes 315 of the top A* Fine Art 24 and A grades, 53% of the cohort achieving A*- B grades and Photography 24 Geography 39 a remarkable 82% achieving A*-C grades. Our BTEC pass rate was 100%, with 80 students achieving 3 Distinction*, Graphic Design 25 HEALTH and SOCIAL CARE the equivalent to three A*s at A Level, in comparison to 57 Art and Design Foundation Diploma 25 Health and Social Care 41 students in 2018. SCIENCES COMPUTING Our students have progressed to exceptional destinations with 10 students advancing to Oxbridge and 24 taking up Biology 26 IT and Computing 43 places on Medicine, Dentistry or Veterinary courses over the Chemistry 26 past 3 years. -

News from Across the Trust February 2020

News from across the Trust Trust training day Our annual trust training day will be held on Friday 3 April 2020. This will be held once again at Malet Lambert, taking advantage of their fantastic hall and forum area. We will be sending out further details in due course but timings will remain the same as last year. Subject CPD Teaching and Learning Library Subject Leaders across the trust have been meeting in their We have recently set up an online teaching and learning library to curriculum teams, focusing on curriculum design as well as enable all teachers to easily access academic text. The current sourcing and developing subject specific CPD. As part of these library includes: • Closing the vocabulary gap , Quigley, Alex meetings, curriculum areas are developing a trust wide shared pool • Reading reconsidered: a practical guide to rigorous literacy of subject specific resources to support teachers across the trust. instruction , Lemov, Doug These will start to be available in the summer term. • Teach like a champion 2.0: 62 techniques that put students on the path to college , Lemov, Doug Teachers have continued to collaborate across the trust and we • The Science of Learning: 77 Studies That Every Teacher have developed bespoke opportunities for teams to work together Needs to Know , Busch, Bradley • The seven myths about education , Christodoulou, Daisy on various aspects of the curriculum including new course • The writing revolution: a guide to advancing thinking through development, standardisation and moderation with the feedback writing in all subjects and grades , Hochman, Judith Wexler, from everyone being overwhelmingly positive. -

Art, Craft and Design Education

Making a mark: art, craft and design education 2008/11 This report evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of art, craft and design education in schools and colleges in England. It is based principally on subject inspections of 96 primary schools, 91 secondary schools and seven special schools between 2008 and 2011. This includes five visits in each phase to focus on an aspect of good practice. The report also draws on institutional inspections, 69 subject inspections in colleges, and visits to a sample of art galleries. Part A focuses on the key inspection findings in the context of the continued popularity of the subject with pupils and students. Part B considers how well the concerns about inclusion, creativity and drawing raised in Ofsted’s 2008 report, Drawing together: art, craft and design in schools, have been addressed. Contents Executive summary 1 Key findings 3 Recommendations 4 The context of art, craft and design education in England 5 Part A: Art, craft and design education in schools and colleges 6 Achievement in art, craft and design 7 Teaching in art, craft and design 14 The curriculum in art, craft and design 25 Leadership and management in art, craft and design 33 Part B: Making a mark on the individual and institution 39 Progress on the recommendations of the last triennial report Promoting achievement for all 41 Providing enrichment opportunities for all 46 Developing artists, craftmakers and designers of the future 48 Focusing on key subject skills: drawing 51 Further information 57 Notes 58 Further information 59 Publications by Ofsted 59 Other publications 59 Websites 59 Annex A: Schools and colleges visited 60 Executive summary Executive summary Children see before they speak, make marks before they Stages 1 and 2 and was no better than satisfactory at Key write, build before they walk. -

INSPECTION REPORT MILLOM SCHOOL Millom LEA Area

INSPECTION REPORT MILLOM SCHOOL Millom LEA area: Cumbria Unique reference number: 112388 Headteacher: Mr L J Higgins Reporting inspector: Bill Stoneham 27407 Dates of inspection: 31st March – 3rd April 2003 Inspection number: 254233 Full inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2003 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Comprehensive School category: Community Age range of students: 11-18 Gender of students: Mixed School address: Salthouse Road Millom Cumbria Postcode: LA18 5AB Telephone number: 01229 772300 Fax number: 01229 772883 Appropriate authority: Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Professor Colin Richards Date of previous inspection: March 1997 Millom School - 3 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Subject Aspect Team members responsibilities responsibilities 27407 Bill Stoneham Registered inspector Business Information about the studies school The school’s results and students’ achievements How well students are taught Leadership -

Lunchtime Supervisor

Lunchtime Supervisor Hours: 6.25 hours per week, Term Time only Contract Type: Permanent Based at Malet Lambert, James Reckitt Avenue, Hull, HU8 0JD Salary: Scp1 £9.25 per hour Malet Lambert School is one of the top performing schools in Hull, where our commitment to pastoral care underpins the high expectations that we have of both pupils and staff. With a long and proud history, dating back to 1932, Malet Lambert School was once a grammar school, becoming a comprehensive school in 1968. We put the needs of individual pupils at the heart of everything we do, and we pride ourselves on having high aspirations, ensuring our pupils meet their potential by creating a safe, yet vibrant, learning environment, which sees first class teaching and learning every single day. We are part of The Education Alliance, a growing multi-academy trust, currently consisting of South Hunsley School and Sixth Form College, Malet Lambert School, Driffield School and Sixth Form, The Snaith School, Hunsley Primary School, North Cave Church of England Primary School and Yorkshire Wolds Teacher Training. We are here to make great schools and happier, stronger communities so that people have better lives. We do this by always doing what is right, trusting each other and standing shoulder to shoulder and doing what we know makes the difference. Doing what is right means always acting with integrity, in the interests of others and being honest, open and transparent. This is an exciting opportunity to join Malet Lambert. You will have a background/knowledge/expertise in supervising students during the midday break as directed by the Senior Midday Supervisor or senior member of staff. -

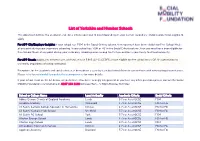

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Royal Holloway University of London Aspiring Schools List for 2020 Admissions Cycle

Royal Holloway University of London aspiring schools list for 2020 admissions cycle Accrington and Rossendale College Addey and Stanhope School Alde Valley School Alder Grange School Aldercar High School Alec Reed Academy All Saints Academy Dunstable All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham All Saints Church of England Academy Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Altrincham College of Arts Amersham School Appleton Academy Archbishop Tenison's School Ark Evelyn Grace Academy Ark William Parker Academy Armthorpe Academy Ash Hill Academy Ashington High School Ashton Park School Askham Bryan College Aston University Engineering Academy Astor College (A Specialist College for the Arts) Attleborough Academy Norfolk Avon Valley College Avonbourne College Aylesford School - Sports College Aylward Academy Barnet and Southgate College Barr's Hill School and Community College Baxter College Beechwood School Belfairs Academy Belle Vue Girls' Academy Bellerive FCJ Catholic College Belper School and Sixth Form Centre Benfield School Berkshire College of Agriculture Birchwood Community High School Bishop Milner Catholic College Bishop Stopford's School Blatchington Mill School and Sixth Form College Blessed William Howard Catholic School Bloxwich Academy Blythe Bridge High School Bolton College Bolton St Catherine's Academy Bolton UTC Boston High School Bourne End Academy Bradford College Bridgnorth Endowed School Brighton Aldridge Community Academy Bristnall Hall Academy Brixham College Broadgreen International School, A Technology -

The Leathersellers Federation of Schools Instruments of Government

Mayor and Cabinet Report Title The Leathersellers’ Federation of Schools Instrument of Government Key Decision Yes Item No. Ward Lewisham Central, Crofton Park, Ladywell Contributors Executive Director for Children and Young People Director of Law Class Part 1 Date: 11 December 2019 1. Summary 1.1 A variation to the Instrument of Government needs to be made for The Leathersellers’ Federation of Schools. The Instrument of Government is being amended to correct a current error and to ensure the Instrument of Government now includes the phrase “Prendergast School is supported by a trust”. 1.2 It is the case that the Instrument of Government must state where a school is supported by a Trust, which Prendergast School has been since its foundation. The variation requested will bring the current Instrument of Government in line with legislation. 2. Purpose 2.1 To seek agreement to the variation of the Instrument of Government for the federation listed below. 3. Recommendation The Mayor is recommended to: 3.1 Approve that the Instrument of Government for The Leathersellers’ Federation of Schools be made by Local Authority order dated 11 December 2019 as set out in Appendix 1. 4. Policy Context 4.1 Each federation has to have an Instrument of Government. The Local Authority must satisfy itself that the Instrument of Government for each federation conforms to the legislation. The Local Authority must also agree its content. 4.2 The report is consistent with the third priority identified in the 2018-2022 Corporate Strategy listed below. 4.3 “Giving children and young people the best start in life - Every child has access to an outstanding and inspiring education and is given the support they need to keep them safe, well and able to achieve their full potential.” 5. -

Newsletter January 2021

NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2021 THE IMPACT OF YWTT TRAINEES IN THEIR HOST SCHOOL PATRICK SPRAKES, HEADTEACHER AT MALET LAMBERT The founding of Yorkshire Wolds Teacher Training was an exciting prospect a few years ago. With Alison Fletcher at the helm, it was always going to be a success, but perhaps even Alison couldn’t have imagined how far the YWTT has come in such a short period of time. Outstanding in every way. I am the Headteacher at Malet Lambert School in East Hull and part of The Education Alliance. Being a partner school of the YWTT has been hugely beneficial for us over the last few years. Right from the off, when YWTT trainees step into school, it is obvious that they have been well prepared, making that potentially huge step seem a lot smaller. The ITT development sessions are crucial for trainees and you can clearly see them having the confidence to put that theory into practice in school, very early on. Malet Lambert encourages its departments to accommodate YWTT trainees where they possibly can. Trainees have often brought new ideas into school and our pupils have benefitted from some excellent lessons and relationships. In some cases, we have had relevant staff vacancies and have made some very successful YWTT permanent appointments over the last few years. Only last term, a previous YWTT trainee was promoted to Head of Geography in only her third year of teaching. This, of course, is a reflection of her skill set and hard work, but the ongoing support from YWTT, The Education Alliance and Malet Lambert during her NQT and RQT years has also been crucial. -

Implementing the English Baccalaureate Government Consultation Response

Implementing the English Baccalaureate Government consultation response July 2017 Contents Foreword from the Secretary of State for Education 4 Introduction 6 Definition of the English Baccalaureate 6 Summary of responses received and the government’s response 8 Summary of the government response 8 Question analysis 11 Question 1: What factors do you consider should be taken into account in making decisions about which pupils should not be entered for the EBacc? 11 Government response 11 Question 2: Is there any other information that should be made available about schools’ performance in the EBacc? 13 Government response 13 Question 3: How should this policy apply to university technical colleges (UTCs), studio schools and further education colleges teaching key stage 4 pupils? 15 Government response 16 Question 4: What challenges have schools experienced in teacher recruitment to EBacc subjects? 17 Question 5: What strategies have schools found useful in attracting and retaining staff in these subjects? 17 Question 8: What additional central strategies would schools like to see in place for recruiting and training teachers in EBacc subjects? 17 Government response to questions 4, 5 and 8 18 Question 6: What approaches do schools intend to take to manage challenges relating to the teaching of EBacc subjects? 19 Question 7: Other than teacher recruitment, what other issues will schools need to consider when planning for increasing the number of pupils taking the EBacc? 20 Government response to questions 6 and 7 20 Question 9: Do you think that any of the proposals have the potential to have an impact, positive or negative, on specific pupils, in particular those with ‘relevant protected characteristics’? (The relevant protected characteristics are disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation).