Making in Mind: the Work of Art in the Age of Theoretical Reproducibility Talia A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G. DELIBRIAS, M. T. GUILLIER and J. LABEYRIE 3430 ± 160 2350 ± 140 1200 ± 120 Gif-168. Plelauff, Cotes Du Nord

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 8, 1966, P. 74-95] GIF NATURAL RADIOCARBON MEASUREMENTS II G. DELIBRIAS, M. T. GUILLIER and J. LABEYRIE Centre des Faibles Radioactivites, C.N.R.S. Gif-sur-Yvette, Essonnes, France The C14 dating laboratories of Saclay (Saclay I, 1964 and Saclay II, 1965) and Gif (Gif-sur-Yvette, 1966) have joined together under the name of Gif C14 Dating Laboratory. The first series of dating results appears here with code designation Gif, Sa now being obsolete. Gif laboratory comprises 3 complete routine sets, each equipped with a 1.2 L proportional counter, filled with pure CO2 at 74 cm Hg pres- sure, having backgrounds of 3.40, 2.90 and 1.60 cpm. The first two are of stainless steel and the third is of OFHC copper. In accordance with the decision of the Fifth Radiocarbon Dating Conference, NBS oxalic acid is adopted as modern carbon reference, and the half-life 5570 yr is used for age calculation. Data listed here are part of those obtained from 1963, the date at which the first counter was calibrated, to October 1965. SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS I. ARCHAEOLOGIC SAMPLES A. Western France 3430 ± 160 Gif-166. Saint-Dude, Bourbriac, Cotes du Nord 1480 B.C. Charcoal from an old burnt soil inside a tumulus at Saint-Dude, Bourbriac (48° 28' N Lat, 3° 18' W Long). Coll. 1962 and subm. by J. Briard and P. R. Giot, Lab. d'Anthropologie Prehistorique, Faculte des Sciences, Rennes, Ille et Vilaine. Comment: dates tumulus to Middle Bronze period. 2350 ± 140 Gif-167. La Belle-Etoile, Saint-Connan, Cotes du Nord 400 B.C. -

Building a Home for Circumpolar Architecture an Introduction

Chapter 1 Building a Home for Circumpolar Architecture An Introduction Robert P. Wishart The hearth is at the centre. It is a simple statement with profound implica- tions. As Stephen Pyne (1995: 3) reminds us, humans are ‘uniquely fire creatures on a uniquely fire planet’. And yet the hearth, the place where we ignite and tend to so many of our fires, is not simply a container for, or a site of, this particularity. Take, for example, the hearth as philosophized and mythologized by the ancient Greeks. Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, was also the goddess of the home, architecture and the symbolic and ritual centre of the inhabitants, the ‘oikos’ or household (Vernant 1969: 132). To the ancient Greeks, the hearth, the home and the household were inseparable, and as Carsten (1995b) illustrates, this understanding is not unique to the classical world. The relatedness of the hearth, the home and the household correspond to the complex and creative relatedness inher- ent in kinship.1 But would it be reductive to understand the house as con- tainer for and site of the household, and would it ignore the coextension of the hearth, house and household with the environment and the cosmos? Furthermore, would these reductions also serve to eclipse real lives with representations that might serve other interests? For the collective effort of the authors gathered here, these questions became fundamental to the inquiry about the ways in which the hearth in the circumpolar North is at the centre of something much larger. There are few other places that one could imagine the crucial interde- pendencies and relationships between the hearth, home and household would be as apparent as that in the circumpolar North. -

Jewellery and Baking Bread at Stainton

Romans on the Don Classroom Exercise 3 Jewellery and Baking Bread at Stainton Three archaeological projects were carried out at Holme Hall near Stainton between 1994 and 2005. The first was fieldwalking which identified an area 60 metres by 80 metres in a field where a large amount of Romano-British pottery was found. This led to geophysical survey and excavation of the area. The site was an Iron Age and Romano-British settlement where bread was baked in kilns during the Roman period. Many features were discovered including a ditched enclosure within which were pits, gullies and postholes, and a hearth. Also inside the enclosure was a cobbled area containing burnt river cobbles that may have been heated in a fire for use in cooking, either to roast meat on or to boil water in pots. The cobbles were thrown aside after use. Outside the enclosure were field boundary ditches, pits, the bases of 3 bread ovens, and a waste midden. The ovens showed that the family who lived in the farm baked their own bread. Wood was placed inside and set a light. When the flames had died down to embers, bread was placed inside the kiln on racks to bake. When ready the racks could be taken out without destroying the roof of the oven. Over 1400 fragments of animal bone were discovered on the site, including cattle, sheep and goat bones. Over 5300 sherds of Roman-British pottery were found, most of it dating from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. The pottery is mainly from jars and a slight increase in table wares over time may show the adoption of Roman table manners in the 3rd century. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 26, No. 3/4. April/July 1965

BULLETIN OF THE MASSACI-IUSETTS ARCI-IAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOL. 26 NOS. 3 and 4 APRIL - JULY, 1965 CONTENTS Page THE BOATS SITE, EXCAVATION NO.2 EDWABD F. ROSE . 33 A BIRDSTONE RECOVERY IN RHODE ISLAND WILLIAM S. FoWLER 39 THE SEMAN SITE: A NEW YORK STATE EXCAVATION PJm..Ip W. JOHANNESSON AND A1mruR C. GLAMM, JR. 44 SIGNIFICANT CERAMIC PIPE RECOVERIES WILLIAM S. FOWLER 49 BITTER ROCK SHELTER: A SThATIFIED CONNECTICUT SITE BERNABD W. POWELL 53 DISCOVERY: AN IMPELLI G FORCE I RESEARCH EDITORIAL 64 PUBLISHED BY THE MASSACHUSmS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, INC. SOCIETY OFFICE, Bronson Museum, 8 No. Main Street, Attleboro, Mass. PEnIOO!CALS DEPT. THE CLfMf iT C. f"AXt', [11_ L1~f!. r;\ Sr!.1~ ,Lr:"E BRIDGE "T'Ii, M/'\;)~ .CHUvElTS MASSACHUSETIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS President Harold F. Nye Marion, Mass. First Vice President Donald C. Wilder 86 Brewster Avenue, South Braintree 85, Mass. Second Vice President William B. Brierly 9 Hawthorne Street, Millbury, Mass. Secretary Maurice Robbins Bronson Museum, Attleboro, Mass. Financial Secretary Mabel A. Robbins 23 Steere Street, Attleboro, Mass. Treasurer Arthur C. Staples Segreganset, Mass. Editor William S. Fowler Bronson Museum, Attleboro, Mass. Trustees Society Officers and 2 Last PliS~ Presidents Walter Thomas, Jr. Edward G. Bielski Robert A. Martin Frank Kremp Robert E. Valyou George S. Gibb MASSACHUSETIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY BULLETIN, pub lished in four Numbers of one Volume each year, commencing in October. Price this issue $1.50 (Subscription by membership in the Society: $3.(0) Note: Address aU requests concerning membership to the Secretary; aU orders for back BuUetin numbers (4 for $1.00 to members) to the Editor; and mail Society dues to the Financial Secretary. -

Cave Painting UNIT 1

All Grades ART ~ Lesson A CYCLE 1 Cave Painting UNIT 1 !! Students will create a cave painting using charcoal and acrylic. Printing"the"Handout" guarantees"families"see" Before the Lesson: the"“home"follow@up" assignment”"and"have" 1.! Review Lesson and Art Handout (below) to understand philosophy and ideas. terms"and"visual"aids" 2.! Print “Animal Template” (below) on card-stock and cut out for"studying"during"the" 3.! Print “Handout” (below) week.""" 4.! Review materials list below and make sure you have everything ready. 5.! Review In-Class section below to make sure you understand the activity. 6.! Optional: Print “ Visual Aids” (below, images are the same as Handout) Materials Needed: !! 1-2 Colors of Acrylic Paint !! 1 Paintbrush per student !! 1 Water Jar per student !! Animal templates (see below, print enough so that each student can have at least one animal at a time). !! 1 11x17 sheet of sketch paper per student !! 1 Willow Stick or piece of charcoal per student Check$with$your$local$ !! 1 Handout on paper, in color per student (or per family) co7op$director"to" !! 1 Large fan know"what"supplies"are" !! Roll of paper towels already"on@hand"and" which"ones"you"need"to" !! Bottle of cleaning spray procure"by"buying"or" !! 1 Smock per student borrowing."""" !! 1 set of Visual Aids on paper, in color (see below, images are same as Handout Feel$free$to$substitute$ materials"when" Classroom Preparation (always plan at least 30 minutes): desired/needed.""" •! Cover the floor with plastic. •! Set up tables throughout the room, covered with plastic. -

The History of Computing in the History of Technology

The History of Computing in the History of Technology Michael S. Mahoney Program in History of Science Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (Annals of the History of Computing 10(1988), 113-125) After surveying the current state of the literature in the history of computing, this paper discusses some of the major issues addressed by recent work in the history of technology. It suggests aspects of the development of computing which are pertinent to those issues and hence for which that recent work could provide models of historical analysis. As a new scientific technology with unique features, computing in turn can provide new perspectives on the history of technology. Introduction record-keeping by a new industry of data processing. As a primary vehicle of Since World War II 'information' has emerged communication over both space and t ime, it as a fundamental scientific and technological has come to form the core of modern concept applied to phenomena ranging from information technolo gy. What the black holes to DNA, from the organization of English-speaking world refers to as "computer cells to the processes of human thought, and science" is known to the rest of western from the management of corporations to the Europe as informatique (or Informatik or allocation of global resources. In addition to informatica). Much of the concern over reshaping established disciplines, it has information as a commodity and as a natural stimulated the formation of a panoply of new resource derives from the computer and from subjects and areas of inquiry concerned with computer-based communications technolo gy. -

Modern Hearth™ Glazed Porcelain Floor & Glazed Ceramic Wall & Mosaic Modern Hearth™ Glazed Porcelain Floor & Glazed Ceramic Wall & Mosaic

CONCRETE LOOK MODERN HEARTH™ GLAZED PORCELAIN FLOOR & GLAZED CERAMIC WALL & MOSAIC MODERN HEARTH™ GLAZED PORCELAIN FLOOR & GLAZED CERAMIC WALL & MOSAIC CONCRETE Modern Interpretation of Vintage Style LOOK Modern Hearth™ combines the tranquility of neutral colors in floor tile with the USAGE surprise of decorative wall tile. This contemporary soft concrete visual in cool and warm tones creates a serene space perfect for rest and relaxation. The three calm, solid colors are available in two floor tile formats, 3 x 12 wall tile and a 2 x 4 brick-joint mosaic. The 6 x 6 decorative wall tile is designed to be installed in a random arrangement of artfully crafted ornamental pieces. • GENTLE WONDER - Serene, soft concrete look available in three neutral and calming colors - 6 x 6 wall tile available in random assortment of beautifully crafted decorative designs in all three colors • COMPREHENSIVE SELECTIONS - Classic 12 x 24 and 12 x 12 floor tile formats and a 2 x 4 brick-joint mosaic - Imaginative 3 x 12 monochromatic and 6 x 6 decorative wall tile - Jolly can be used as a coordinating trim or wall accent SEE CHARTS FOR FULL Cover photo features Modern Hearth™ Chimney Corner 12 x 24 floor tile on the floor and PRODUCT DETAILS Modern Hearth™ Ash White 6 x 6 decorative wall tile on the wall. Above photo features Modern Hearth™ Chimney Corner 6 x 6 decorative wall tile on the backsplash. CONCRETE LOOK MODERN HEARTH™ GLAZED PORCELAIN FLOOR & GLAZED CERAMIC WALL & MOSAIC SIZES: 2 x 4 Brick-joint 12 x 24 12 x 12 3 x 12 6 x 6 Decorative Mosaic Floor -

Comparison of Different Bf-Hearth Lining Design Technologies1

COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT BF-HEARTH LINING DESIGN TECHNOLOGIES1 Jean-Philippe Houde2 Rudolf Hebel3 Volker Dulz4 Abstract One of the BF-owner’s important requirements is the BF-hearth lining life time extension up to 20 years or more, without any intermediate repairs. A number of different hearth lining designs were developed in the last decades. Some well experienced and successful hearth lining technologies were presented. The main targets of this paper are explanations of excellent hearth lining life times as well as good operation experiences. Further on, the paper shows that the goal to reach the main targets is depending on a number of different boundary conditions. The most important boundary conditions to extend the hearth lining life campaign will be illuminated and explained with the assistance of different lining design examples. Key words: BF-hearth lining life time extension; Hearth lining wear reduction; Hearth characteristic indexes; Hearth lining design comparison. 1 Technical contribution to the 43rd Ironmaking and Raw Materials Seminar, 12h Brazilian Symposium on Iron Ore and 1st Brazilian Symposium on Agglomeration of Iron Ore, September 1st to 4th, 2013, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 Chemical Engineer, Head of Blast Furnace Department, Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering GmbH, Mainz-Kastel, Germany. 3 Dipl. Engineer, Consultant, Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering GmbH, Mainz-Kastel, Germany. 4 Civil Engineer, Deputy Head of Blast Furnace Department, Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering GmbH, Mainz-Kastel, Germany. 1 INTRODUCTION The evolution of technologies in the last decades has leaded the BF owner to expect long campaign life time as shown on Figure 1. Figure 1. Blast Furnace repair cycle. -

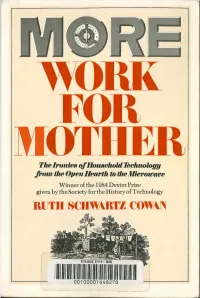

More Work for Mother

The It--onies ofHousehohl'JeehnowgiJ ft--om the Open Heat--th to the Miet--owave Winner of the 1984 Dexter Prize given by the Society for the History of Technology -RUTH SCHWARTZ COWAN ETHICS ETH·- BIB II II 111111 II II II llllllllllllll II 00100001648270 More Work for Mother MORE WORK FOR MOTHER The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave Ruth Schwartz Cowan • BasicBooks- A Division of HarperCollinsPub/ishen Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cowan, Ruth Schwartz, 1941- More work for mother. Bibliography: p. 220 Includes index. 1. Horne economics-United States-History. 2. Household appliances-United States-History. 3. Housewives-United States-History I. Title. II. Title: Household technology from the open hearth to the microwave. TX23.C64 1983 640'.973 83-70759 ISBN 0-465-04731-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-465-04732-7 (paper) Copyright © 1983 by Basic Books, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre 10 9 8 7 For Betty Schwartz and Louis E. Schwartz with love Contents PICTURE ESSAYS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS XI Chapter 1 An Introduction: Housework and Its Tools 3 Chapter 2 Housewifery: Household Work and Household Tools under Pre-Industrial Conditions 16 Housewifery and the Doctrine of Separate Spheres 18 Household Tools and Household Work 20 The Household Division of Labor 26 The Household and the Market Economy 31 Conclusion 3 7 Chapter 3 The Invention of Housework: The Early Stages of Industrialization 40 Milling Flour and Making Bread 46 The Evolution of the Stove 53 More Chores -

AWARDS ANNUAL MEETING Milano 24-27 October

2019 SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF TECHNOLOGY AWARDS ANNUAL MEETING milano 24-27 october www.historyoftechnology.org In 2020 the SHOT Annual Meeting takes place in New Orleans, Louisiana (USA), 7-11 October. CONTENTS Society for the History of Technology. 2 2019 Prize Committees .................................................... 3 2019 Awards and Fellowships ............................................... 9 Awards, Grants and Fellowships Special Interest Groups .......................... 22 Previous winners .......................................................... 25 SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF TECHNOLOGY President Tom Misa University of Minnesota Vice President Arwen Mohun University of Delaware Secretary Jan Korsten Foundation for the History of Technology Treasurer Amy Bix Iowa State University Editor-in-Chief Suzanne Moon University of Oklahoma 2 SHOT Awards 2019 2019 PRIZE COMMITTEES Leonardo da Vinci Medal The highest recognition from the Society for the History of Technology is the Leonardo da Vinci Medal, presented to an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the history of technology, through research, teaching, publication, and other activities. Andras Beck (formerly of the Hungarian Academy of Arts) designed the medal, the face of which shows Leonardo’s head modeled after the artist’s self-portrait. The reverse design shows (in the words of the sculptor) “the basic sources of energy: water, wind, and fire.” A certificate accompanies the medal. John Krige (Chair), Georgia Institute of Technology Jennifer Alexander, -

The Prehistoric Cave Art and Archaeology of Dunbar Cave, Montgomery County, Tennessee

J.F. Simek, S.A. Blankenship, A. Cressler, J.C. Douglas, A. Wallace, D. Weinand, and H. Welborn – The prehistoric cave art and archaeology of Dunbar Cave, Montgomery County, Tennessee. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 74, no. 1, p. 19–32. DOI: 10.4311/ 2011AN0219 THE PREHISTORIC CAVE ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF DUNBAR CAVE, MONTGOMERY COUNTY, TENNESSEE JAN F. SIMEK1*,SARAH A. BLANKENSHIP1,ALAN CRESSLER2,JOSEPH C. DOUGLAS3,AMY WALLACE4, DANIEL WEINAND1, AND HEATHER WELBORN1 Abstract: Dunbar Cave in Montgomery County, Tennessee has been used by people in a great variety of ways. This paper reports on prehistoric uses of the cave, which were quite varied. The vestibule of the cave, which is today protected by a concrete slab installed during the cave’s days as an historic tourist showplace, saw extensive and very long term occupation. Diagnostic artifacts span the period from Late Paleo-Indian (ca.10,000-years ago) to the Mississippian, and include Archaic (10,000 to 3,000-years ago) and Woodland (3,000–1,000-years ago) cultural materials. These include a paleoindian Beaver Lake Point, Kirk cluster points, Little River types, Ledbetter types, numerous straight-stemmed point types, Hamilton and Madison projectile points. Woodland period ceramics comprise various limestone tempered forms, all in low quantities, and cord-marked limestone tempered wares in the uppermost Woodland layers. Shell-tempered ceramics bear witness to a rich Mississippian presence at the top of the deposit. Given this chronological span, the Dunbar Cave sequence is as complete as any in eastern North America. However, problems with previous excavation strategies make much of the existing archaeological record difficult to interpret. -

Alpharetta, GA Raises the Standard for Excellence in Culinary Travel and Experiences Across the Board the City of Alpharetta Is Doing More for Dining

Alpharetta, GA Raises the Standard for Excellence in Culinary Travel and Experiences Across the Board the City of Alpharetta is Doing More for Dining ALPHARETTA, GA ̶ June 2018 ̶ The quest for authentic dining experiences and culinary excellence continues to be a powerful driver of tourism, and the city of Alpharetta, Ga. boasts an unbeatable lineup of top-notch eateries and one-of-a-kind culinary hot spots. The city’s well- established and eclectic dining scene continues to break the mold and challenge the idea that big time flavors are only found in big cities. “Alpharetta offers visitors countless ways to enjoy an exciting dining experience,” said Janet Rodgers, president and CEO of the Alpharetta Convention & Visitors Bureau. “Alpharetta is a haven for both chefs and diners alike. With more than 200 unique culinary experiences, each featuring one-of-a-kind, chef-driven dishes, our colorful culinary scene showcases the best in local, regional and international flavors.” Whether travelers are on the hunt for the perfect happy hour spot, hand-crafted cuisine, international eats or for ways to seamlessly combine food and fun, there is something for every palate awaiting in Alpharetta. Happy Hours Done Better After a day of work, long conference sessions or an action-packed afternoon of exploring the 300+ things to do in Alpharetta, guests can venture to one of the city’s many eateries specializing in unique happy hour experiences. One must-see spot for visitors is MADE Kitchen & Cocktails located in Alpharetta’s charming and upbeat downtown area. While the menu offers an incredible lineup of tasty treats, bartender Christian Zak steals the show with an everchanging menu of artisan cocktails featuring Zak’s own distilled liquor, homemade bitters and even a handful of unique and refreshing limoncello flavors created as a dessert alternative.