7 the Hand of God, and Other Soccer . . . Miracles?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 April 1992 Opposition: Leeds United Competition

1 Times Guardian Sunday Times 8 Date: 18 April 1992 April British Soccer Wk Opposition: Leeds United 1992 Competition: League Leeds cling on by Lukic’s fingertips All-square and all to play for as suspense lingers on JOHN Lukic has prolonged the championship race, and perhaps at a great personal NEVER mind the quality, concentrate on the figures. The last Football League loss. In keeping out Liverpool in Saturday's goalless draw at Anfield, the Leeds championship before the Premier League takes over has been among the poorest United goalkeeper may inadvertently have ruled himself out of contention for a on record, but the statistics promise to keep everyone in suspense for at least place in England's squad for the European chip als in June. another week. The only thing decided on Saturday was that the title cannot be Advised to apply for a visa, he had already unofficially been invited to go to decided today. Manchester United's 11 draw at Luton kept them top simply Moscow in a fortnight for the last of the England manager's experiments this because Leeds United could manage no better than a goalless draw at Liverpool. seaso. If the leaders beat Nottingham Forest at Old Trafford this afternoon Leeds will The party is to be anounced tomorrow but Lukic is now unlikely to be available. start their televised match against Coventry City at tea-time five points behind Unless Leeds subside at home to Coventry City today and at Sheffield United on with three fixtures remaining. Sunday, they will still be challenging for the title on closing day, May 2. -

Maradona Entre La Tierra Y El Cielo*

013-025:013-24 Méndez Rubio.qxd 03/11/2015 13:14 Página 13 Maradona entre la tierra y el cielo* Marcello SERRA Universidad Carlos III […] no resultaba tan fácil olvidar que Maradona venía come- tiendo desde hacía años el pecado de ser el mejor, el delito de denunciar a viva voz las cosas que el poder manda callar y el crimen de jugar con la zurda, lo cual, según el Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado, significa “con la izquierda” y también sig- nifica “al contrario de cómo se debe hacer”. Eduardo Galeano, El fútbol a sol y sombra (Abstracts y palabras clave al final del artículo) Enviado: 1 de mayo de 2015 Aceptado: 2 de mayo de 2015 Diego Armando Maradona. El cine le ha dedicado películas y documentales. La música popular le ha cantado himnos en los géneros más diver- sos. Tatuada en la piel de miles de aficionados aparece la reproducción de su cara, de una jugada suya, de un autógrafo o del número que desde siempre lo ha distin- guido, el diez, y que aparece también en el centro del lema con el que lo designan muchos de sus aficionados: D10S. Porque lo de Maradona es un verdadero culto. El bar Nilo, por ejemplo, es un local tradicional justo en el centro de Nápoles. Según los usuarios de TripAdvisor el café es bueno, pero lo que lo hace distinto de cual- quier otro bar napolitano es la presencia de una graciosa reliquia. Un pequeño altar de tonalidades azules muestra un “sagrado cabello milagroso” de Maradona, objeto de pere- grinaciones de hinchas y apasionados del fútbol, exhibido junto a un frasquito supuesta- mente lleno de lágrimas vertidas por los napolitanos en el momento de su despedida. -

Similitudes a Distinto Nivel. De Brian Clough a Antonio Oviedo

Cuadernos de Fútbol Revista de CIHEFE https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol Similitudes a distinto nivel. De Brian Clough a Antonio Oviedo. Autor: Sebastià Ramis Guasp Cuadernos de fútbol, nº 68, septiembre 2015. ISSN: 1989-6379 Fecha de recepción: 05-08-2015, Fecha de aceptación: 17-08-2015. URL: https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol/2015/09/titulo-similitudes-a-distinto-nivel-de-brian- clough-a-antonio-oviedo/ Resumen Un partido amistoso entre Nottingham Forest y RCD Mallorca en Cala Millor el 19 de mayo de 1981 permite que dos entrenadores, adelantados a su tiempo pero con diferentes destinos, se encuentren cara a cara. Dos entrenadores que consiguieron con sus respectivos equipos grandes hitos y que hoy en día siguen en vigor y recordando. Palabras clave: Antonio Oviedo, Brian Clough, futbol, historia, Nottingham ForestRCD Mallorca Abstract Keywords:Antonio Oviedo, Brian Clough, Football, History, Nottingham Forest, RCD Mallorca A friendly match between Nottingham Forest and RCD Mallorca in Cala Millor on May 19th, 1981, allows that two coaches, ahead of their time but with different destinies, meet face to face. Two coaches that marked with their respective teams significant milestones still well remembered today. Date : 1 septiembre 2015 1 / 8 Cuadernos de Fútbol Revista de CIHEFE https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol El 19 de mayo de 1981 se inauguraba el complejo deportivo Badia de Cala Millor, situado entre los pueblos de Son Servera y Sant Llorenç des Cardassar. Para la inauguración se contó ni más ni menos que con la presencia del Nottingham Forest de Brian Clough y Peter Taylor, ambos asiduos residentes durante los veranos de la década de los setenta y ochenta. -

The Hand of God: Diego Maradona and the Divine Nature of Cheating In

The hand of God: Diego Maradona and the divine nature of cheating in Classical Antiquity Autor(es): Ahl, Frederick Publicado por: Annablume Clássica; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/36122 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/1984-249X_14_1 Accessed : 6-Oct-2021 22:38:36 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt desígnio 14 jan/jun 2015 A MÃO DE DEUS: DIEGO MARADONA E A NATUREZA DIVINA DA TRAPAÇA NA ANTIGUIDADE CLÁSSICA. HE AND OF OD IEGO ARADONA AND THE IVINE ATURE OF HEATING T H G : D M D N C * IN CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY Frederick Ahl AHL, F. -

Diego Maradona

DIEGO MARADONA A film by ASIF KAPADIA 2019 – UK – 130 minutes INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY ALTITUDE FILM SALES Karina Gechtman, Head of International ORGANIC Marketing and Publicity Organicinternational@organic- [email protected] publicity.co.uk DIEGO MARADONA – PRODUCTION NOTES DIEGO MARADONA SHORT SYNOPSIS The third film from the Academy Award® and BAFTA-winning team behind SENNA and AMY, and producer Paul Martin, DIEGO MARADONA is constructed from over 500 hours of never-before-seen footage from Maradona’s personal archive with the full support of the man himself. On 5th July 1984, Diego Maradona arrived in Naples for a world-record fee. For seven years all hell broke loose. The world’s most celebrated football icon and the most passionate but dangerous city in Europe were a perfect match for each other. On the pitch, Diego Maradona was a genius. Off the pitch, he was treated like a God. The charismatic Argentine loved a fight against the odds and led Napoli to their first-ever title. It was the stuff of dreams. But there was a price… Diego could do as he pleased while performing miracles on the pitch but, as time passed, darker days closed in. LONG SYNOPSIS Diego Maradona was considered the best player in the world from the moment he burst onto the scene in his native Argentina. And yet success proved elusive. He failed at Barcelona. He was considered a problem player, too interested in partying. Meanwhile, having never won a major tournament, the ailing Italian football giant SSC Napoli were perennial underachievers. Their fanatical support was unequalled in both passion and size. -

When Diego Maradona Visited Qatar for the Opening of Aspire Academy

A very sad day for all Argentines and football. He has left us but he will never leave us because Diego is eternal. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2020 – Lionel Messi ‘Eternal’ Maradona’s passing away plunges football world into mourning Argentina’s football team captain Diego Maradona kisses the World Cup trophy won by his team after a 3-2 victory over West Germany at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, watched by Mexican President Miguel de La Madrid (left) and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, In this file photo taken on January 7, 2013, SSC Napoli’s fans display a flag with the effigy of Napoli’s former Argentinian player Diego Armando Maradona during the Serie A match on June 29, 1986. (AFP) vs AS Roma at San Paolo Stadium in Naples. (AFP) AFP “Always in our hearts, Ciao tion, notably to cocaine, and his own half. Diego is eternal. farewell to Maradona, who logo on their social media ac- LONDON Diego.” Boca posted: “Eternal with his weight, in contrast “By some distance the best “I will keep all the beauti- won the hearts of the south- counts to black. thanks. Eternal Diego.” to the more clean-cut image player of my generation and ful moments that I lived with ern Italian city of Naples by Maradona spent seven THE football world united Maradona also played for of Brazilian legend and three- arguably the greatest of all him and would like to send my leading the club to its only two years at then-unfashionable to pay tribute to one of the Barcelona and Sevilla in Eu- time World Cup winner Pele. -

Lma Diploma in Football Management

LMA DIPLOMA IN FOOTBALL MANAGEMENT 2020-2021 CONTENTS Achieving your ambitions 05 Course module overview 06 Course calendar 10 Entry requirements 13 The home of English football 14 The LMA Learning and Personal Development Model 16 LMA Institute events 19 Fee contribution and how to apply 21 Alumni 22 ACHIEVING YOUR AMBITIONS The LMA Institute offers those looking for a formal qualification the opportunity to obtain a Diploma in Football Management, in partnership with the University of Liverpool. This one-year course consists of a residential week at the start and end, with 7 one-day masterclasses throughout the year. Assessment is via assignments, group work and presentations. This programme continues to evolve to ensure it remains relevant to those working in “THE LMA DIPLOMA IN professional football and those who aspire to become managers. FOOTBALL MANAGEMENT The LMA Diploma in Football Management enhances your leadership abilities, sharpens your strategic thinking, gives practical insights into the modern practices of sports PROVIDES A BRIDGE BETWEEN performance management and gives you a broader perspective on the many challenges THE GAME’S COACHING and complexities of the football industry. The programme builds on your proven talent QUALIFICATIONS AND THE and experience to deliver a set of practical skills that you use as you build your career. REALITIES OF MANAGEMENT The Diploma challenges its students to raise their game, confront their knowledge gaps and refine their skill set. It inspires peer-to-peer learning, with all students sharing IN THE MODERN GAME.” their experiences in a rich, collaborative learning environment. It brings together an HOWARD WILKINSON, experienced group of lecturers, experts and industry insiders, as well as engaging with LMA CHAIRMAN many of the LMA’s senior members to share their real-life experiences in the game. -

Dios Y Los Diez: the Mythologization of Diego Maradona and Lionel

Dios y los Diez: The Mythologization of Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi in Contemporary Argentina Catherine Addington Senior Thesis, New York University Latin American Studies Advisor: Mariano López Seoane March 28, 2015 Addington 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 List of Images 2 Abstract 4 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 7 Part I: Identity and Globalization 18 Part II: Citizenship and Consumerism 34 Part III: Ritual and Reverence 49 Conclusion 64 Works Cited 67 Addington 2 List of Images Image 1 .............................................................................................................................. 6 Retratos de Maradona y Messi. N.d. Mural. Punto Urbano Hostel, Mendoza, Argentina. Photograph by Catherine Addington. Image 2 ............................................................................................................................ 17 Brindicci, Marcos. “Maradona’s childhood home in Villa Fiorito.” Photograph. “Here & Gone.” ESPN, 5 October 2012. Web. 1 March 2015. Image 3 ............................................................................................................................ 17 Gupta, Jayaditya. “Lionel Messi’s home in Rosario.” Photograph. “Tracing Lionel Messi in sleepy Rosario.” LiveMint, 24 June 2014. Web. 2 March 2015. Image 4 ............................................................................................................................ 33 “Maradona with the 1986 World Cup.” Photograph. McGovern, Derek. “Is Lionel Messi Better Than Diego Maradona?” The -

The Institute

THE INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP AND HIGH PERFORMANCE EXCELLENCE THROUGH INSIGHT 00 “WE ARE IN AN ERA WHEN IT’S NEVER BEEN MORE DIFFICULT TO BUILD A CAREER IN MANAGEMENT. WE ALL NEED TO KEEP LEARNING, KEEP DEVELOPING AND MOVE THE GAME FORWARD” CHRIS HUGHTON 00 LMA INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP AND HIGH PERFORMANCE The LMA Institute of Leadership and High Performance has been established to provide ongoing learning and continuous personal development to those working in professional football. Through innovative learning programmes, the LMA continues to develop opportunities that are relevant and tailored to individual requirements. EXCELLENCE THROUGH INSIGHT The Institute combines the best principles of adult, in-career learning with the knowledge, insight and experiences of high achievers and world-class experts from football, elite sport, education and other leadership disciplines. 05 LMA INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP AND HIGH PERFORMANCE LMA PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT MODEL The LMA Institute is guided by the LMA Personal Development Model: You, Your Team, The Game, The Industry, and delivers a broad spread of content linked to each pillar. YOU YOUR TEAM n Wellbeing n High performance teams n Mental toughness n Backroom teams n Leadership styles n Transformational leadership n Personal psychological profiling n Motivation and engagement n Mental resilience n Change leadership n Building your brand n Neuroscience and talent n Career pathways development n Mentoring n Diversity, equality and inclusion THE INDUSTRY THE GAME THE LMA DIPLOMA IN FOOTBALL MANAGEMENT n Regulatory environment n Tactics n Football finances and economics n Analytics n The commercial world of football n Sport science The LMA Institute offers those looking for a formal n Stakeholder analysis n Sport psychology qualification the opportunity to obtain a Diploma in Football n Talent identification Management, in partnership with the University of Liverpool. -

Printable Checklist

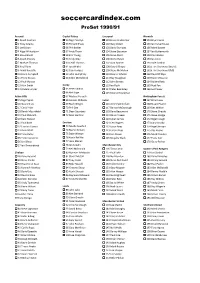

soccercardindex.com ProSet 1990/91 Arsenal Crystal Palace Liverpool Norwich 1 David Seaman 54 Nigel Martyn 101 Bruce Grobbelaar 154 Bryan Gunn 2 Tony Adams 55 Richard Shaw 102 Gary Ablett 155 Ian Culverhouse 3 Lee Dixon 56 Phil Barber 103 David Burrows 156 Mark Bowen 4 Nigel Winterburn 57 Andy Thorn 104 Steve Staunton 157 Ian Butterworth 5 Steve Bould 58 Eric Young 105 Steve Nicol 158 Paul Blades 6 David O'Leary 59 Andy Gray 106 Glenn Hysen 159 Ian Cook 7 Michael Thomas 60 Geoff Thomas 107 Alan Hansen 160 Dale Gordon 8 Paul Davis 61 Ian Wright 108 Gary Gillespie 161a Tim Sherwood (waist) 9 David Rocastle 62 Glyn Hodges 109 Steve McMahon 161b Tim Sherwood (full) 10 Kevin Campbell 63 John Humphrey 110 Ronnie Whelan 162 David Phillips 11 Perry Groves 64 Eddie McGoldrick 111 Ray Houghton 163 Robert Rosario 12 Paul Merson 112 John Barnes 164 Robert Fleck 13 Alan Smith Derby 113 Ian Rush 165 Ruel Fox 14 Anders Limpar 65 Peter Shilton 114 Peter Beardsley 166 Les Power 66 Mel Sage 115 Ronnie Rosenthal Aston Villa 67 Michael Forsyth Nottingham Forest 15 Nigel Spink 68 Geraint Williams Luton 167 Brian Laws 16 Stuart Gray 69 Mark Wright 116 Alec Chamberlain 168 Stuart Pearce 17 Chris Price 70 Phil Gee 117 Darron McDonough 169 Des Walker 18 Derek Mountfield 71 Dean Saunders 118 Dave Beaumont 170 Steve Chettle 19 Paul McGrath 72 Mick Harford 119 David Preece 171 Steve Hodge 20 Kent Nielson 120 Julian James 172 Nigel Clough 21 Paul Birch Everton 121 Ceri Hughes 173 Gary -

EPL 1994-95 Team Cards

1994-95 BLACKBURN ROVERS (HOME) STARTERS PP SP GS SB G PK R SH0T Tim FLOWERS GK 39 0 0 - 921 -- Ian PEARCE DR 22 6 0 915 -3 Henning BERG DC 40 0 1 921 -1 Colin HENDRY DC 38 0 4 921 7 Graeme LE SAUX DL 39 0 3 921 4 Tim SHERWOOD AM 38 0 6 922 -1 Stuart RIPLEY DM 36 1 0 920 -3 Jason WILCOX DM 27 0 5 917 -1 Mark ATKINS AM 30 4 6 919 0 Chris SUTTON F 40 0 15 924 0 Alan SHEARER F 42 0 24 10 928 2 BENCH PP SP GS SB G PK R SH0T Jeff KENNA DL 9 0 1 920 3 Paul WARHURST AM 20 7 2 915 -3 Tony GALE DC 15 0 0 912 -3 Robbie SLATER DM 12 6 0 911 -3 Alan WRIGHT DL 4 1 0 911 -3 David BATTY DM 4 1 0 908 -3 Mike NEWELL F 2 10 0 908 -1 Bobby MIMMS GK 3 1 0 - 908 -- Kevin GALLACHER F 1 0 1 907 3 Richard WITSCHGE DM 1 0 0 907 -3 1994-95 MANCHESTER UNITED (HOME) STARTERS PP SP GS SB G PK R SH0T Peter SCHMEICHEL GK 32 0 0 - 922 -- Gary NEVILLE DR 16 2 0 916 -3 Gary PALLISTER DC 42 0 2 926 1 Steve BRUCE DC 35 0 2 923 2 Denis IRWIN DL 40 0 1 1 925 -1 Paul INCE AM 36 0 5 924 -2 Ryan GIGGS DM 29 0 1 921 -2 Brian MCCLAIR DM 35 5 5 924 -2 Andrei KANCHELSKIS AM 25 5 14 922 6 Mark HUGHES F 33 1 8 924 -2 Eric CANTONA F 17 1 12 927 4 BENCH PP SP GS SB G PK R SH0T Andy COLE F 21 0 8 4 925 0 Lee SHARPE M 26 2 3 920 -1 Roy KEANE DM D 23 2 2 919 0 Keith GILLESPIE AM 3 6 1 917 1 David MAY DC 15 4 2 916 5 Nicky BUTT DM 11 11 1 915 -1 Paul SCHOLES AM 6 11 5 914 3 Gary WALSH GK 10 0 0 - 914 1 Simon DAVIES DM 3 2 0 911 -3 David BECKHAM AM 2 2 0 911 -1 Phil NEVILLE D 1 1 0 911 -3 Paul PARKER D 1 1 0 911 -3 Kevin PILKINGTON GK 0 1 0 - 910 -- 1994-95 NOTTINGHAM FOREST (HOME) STARTERS -

Bucks Free Press - August 1990

originally published by the Bucks Free Press - August 1990 A Bucks Free Press PUBLICATION scanned and digitally enhanced by chairboys.co.uk for 25th anniversary of opening of Adams Park - August 2015 originally published by the Bucks Free Press - August 1990 Wycombe Wanderers' supplement Page2 : (. Chicago deep pan, italian thin crust, fresh baked pizza "built to order" Running up the Carry Out Restaurant Open 7 days BEACONSFIELD (0494) 675429 slope for 95 years 34 Gregories Road, Beaconsfield LOAKES Park has carved its own special place in the hearts of Wycombe Wan derers' loyal supporters. UNBEATABLE PRICES It was with heavy hearts, '5lj therefore, that they paid· ~ ~ GIFT VOUCHERS homage to a sloping ~ ~ AVAILABLE ground which possesses a rich 95-year history. Fis h and Reptile equipment specialists, Tropical Here is the history of Fish, Marine Fish and Invertebrates, Co ldwater Loakes Park in summary Fis h, Aquatic Plants, Pond Equipment form: To be a responsible Aquarist, use on ly Aquaria etc. In 1894 the club decided Free expe rt advice and support given by specialists. to rent Spring Meadows to (OPEN SEVEN DAYS A WEE K) get away from the difficult conditions on the Rye. VI SIT OUR SHOWROOM AT Lord Carrington was ap 34 TOTTERIDGE ROAD, HIGH WYCOMBE proached to see if Loakes TEL (0494) 473433 Park could be rented. The first match to be played at Loakes Park was a friendly against Park Grove on September 7, 1895. On May 21, 1896, it was announced that Wy MOT TESTS combe's application to join the Southern League had been accepted.