Maradona Inc: Performance Politics Off the Pitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fis Hm an Pele, Lio Nel Messi, and More

FISHMAN PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE JON M. FISHMAN Lerner Publications Minneapolis SCORE BIG with sports fans, reluctant readers, and report writers! Lerner Sports is a database of high-interest LERNER SPORTS FEATURES: biographies profiling notable sports superstars. Keyword search Packed with fascinating facts, these bios Topic navigation menus explore the backgrounds, career-defining Fast facts moments, and everyday lives of popular Related bio suggestions to encourage more reading athletes. Lerner Sports is perfect for young Admin view of reader statistics readers developing research skills or looking Fresh content updated regularly for exciting sports content. and more! Visit LernerSports.com for a free trial! MK966-0818 (Lerner Sports Ad).indd 1 11/27/18 1:32 PM Copyright © 2020 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Main body text set in Aptifer Sans LT Pro. Typeface provided by Linotype AG. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fishman, Jon M., author. Title: Soccer’s G.O.A.T. : Pele, Lionel Messi, and more / Jon M. -

Maradona Entre La Tierra Y El Cielo*

013-025:013-24 Méndez Rubio.qxd 03/11/2015 13:14 Página 13 Maradona entre la tierra y el cielo* Marcello SERRA Universidad Carlos III […] no resultaba tan fácil olvidar que Maradona venía come- tiendo desde hacía años el pecado de ser el mejor, el delito de denunciar a viva voz las cosas que el poder manda callar y el crimen de jugar con la zurda, lo cual, según el Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado, significa “con la izquierda” y también sig- nifica “al contrario de cómo se debe hacer”. Eduardo Galeano, El fútbol a sol y sombra (Abstracts y palabras clave al final del artículo) Enviado: 1 de mayo de 2015 Aceptado: 2 de mayo de 2015 Diego Armando Maradona. El cine le ha dedicado películas y documentales. La música popular le ha cantado himnos en los géneros más diver- sos. Tatuada en la piel de miles de aficionados aparece la reproducción de su cara, de una jugada suya, de un autógrafo o del número que desde siempre lo ha distin- guido, el diez, y que aparece también en el centro del lema con el que lo designan muchos de sus aficionados: D10S. Porque lo de Maradona es un verdadero culto. El bar Nilo, por ejemplo, es un local tradicional justo en el centro de Nápoles. Según los usuarios de TripAdvisor el café es bueno, pero lo que lo hace distinto de cual- quier otro bar napolitano es la presencia de una graciosa reliquia. Un pequeño altar de tonalidades azules muestra un “sagrado cabello milagroso” de Maradona, objeto de pere- grinaciones de hinchas y apasionados del fútbol, exhibido junto a un frasquito supuesta- mente lleno de lágrimas vertidas por los napolitanos en el momento de su despedida. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Sport De Rue Et Vidéo Avec Ph

Chapitre X DE LA RUE AU STADE : POINTS DE VUE CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUES Jean-Pascal FONTORBES1 MCF HDR Cinéma « L’instituteur au cours moyen me donnait des « bouffes » parce que j’arrivais de la récréation en sueur » (Jean Trillo, 2014, extrait d’entretien filmé). Nos travaux de création et d’analyse filmiques depuis notre première production en 1981 sont consacrés notamment au dévoilement des constructions identitaires personnelles et collectives, sociales, professionnelles, culturelles et sportives. Nos observations se centrent sur les interactions sociales. Le cinéma nous oblige à nous interroger sur la manière dont est représenté le monde dont sont mises en scène les identités. L’écriture cinématographique est pertinente pour la lecture audiovisuelle des récits et des pratiques. Les valeurs sportives n’existent pas indépendamment des acteurs. C’est à partir de l’empirie, des observations de terrain, des récits et des pratiques recueillis et filmés que nous tentons de comprendre comment le sport prend place dans la rue, dans l’espace public, dans l’espace ouvert et de saisir les mécanismes des constructions sociales et corporelles qui lui sont liés. Notre analyse est contextualisée : elle prend en compte des aires géographiques et culturelles différentes. Le premier film se situe dans un village du Sénégal et en France, le second en Argentine et d’abord dans la banlieue de Buenos Aires, le troisième dans un village des Landes. Nous nous intéressons, plus particulièrement, à l’enfance et à l’adolescence. Nous croisons pratiques sportives, jeunesse et lieux. Notre propos est construit à partir de trois extraits de films, deux documentaires et une fiction qui ont en commun de rendre compte de réalités vécues, à partir d’histoires de vie de trois sportifs de haut niveau : « Comme un lion » de Samuel Collardey, 2011 Mitri est un adolescent qui habite un village au Sénégal. -

Goal Celebrations When the Players Makes the Show

Goal celebrations When the players makes the show Diego Maradona rushing the camera with the face of a madman, José Mourinho performing an endless slide on his knees, Roger Milla dancing with the corner flag, three Brazilians cradling an imaginary baby, Robbie Fowler sniffing the white line, Cantona, a finger to his lips contemplating his incredible talent... Discover the most fantastic ways to celebrate a goal. Funny, provo- cative, pretentious, imaginative, catch football players in every condition. KEY SELLING POINTS • An offbeat treatment of football • A release date during the Euro 2016 • Surprising and entertaining • A well-known author on the subject • An attractive price THE AUTHOR Mathieu Le Maux Mathieu Le Maux is head sports writer at GQ magazine. He regularly contributes to BeInSport. His key discipline is football. SPECIFICATIONS Format 150 x 190 mm or 170 x 212 mm Number of pages 176 pp Approx. 18,000 words Price 15/20 € Release spring 2016 All rights available except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com contENTS The Hall of Fame Goal celebrations from the football legends of the past to the great stars of the moment: Pele, Eric Cantona, Diego Maradona, George Best, Eusebio, Johan Cruijff, Michel Platini, David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Drogba, Ronaldo, Messi, Thierry Henry, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Balotelli, Zlatan, Neymar, Yekini, Paul Gascoigne, Roger Milla, Tardelli... Total Freaks The wildest, craziest, most unusual, most spectacular goal celebrations: Robbie Fowler, Maradona/Caniggia, Neville/Scholes, Totti selfie, Cavani, Lucarelli, the team of Senegal, Adebayor, Rooney Craig Bellamy, the staging of Icelanders FC Stjarnan, the stupid injuries of Paolo Diogo, Martin Palermo or Denilson.. -

Land Tenancy, Soybean, Actors and Transformations in the Pampas: a District Balance Hernán A

Land tenancy, soybean, actors and transformations in the pampas: A district balance Hernán A. Urcola, Xavier Arnauld de Sartre, Iran Veiga, Julio Elverdín, Christophe Albaladejo To cite this version: Hernán A. Urcola, Xavier Arnauld de Sartre, Iran Veiga, Julio Elverdín, Christophe Albaladejo. Land tenancy, soybean, actors and transformations in the pampas: A district balance. Journal of Rural Studies, Elsevier, 2015, 39, pp.32-40. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.03.001. halshs-01252579 HAL Id: halshs-01252579 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01252579 Submitted on 8 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Land tenancy, soybean, actors and transformations in the pampas: A district balance1 a b c a Hernán A. URCOLA , Xavier ARNAULD DE SARTRE , Iran VEIGA , Julio ELVERDIN , Christophe Albaladejod a. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), Laboratoire AGRITERRIS, Economía y Sociología Rural INTA, Ruta 226, Km 73,5 (7620) Balcarce, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Te: +54-2266-439105, int 221 Fax: +54-2266-439101 Email: [email protected] [email protected] b. UMR Société environnement territoire Centre national de la recherche scientifique / Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour Domaine universitaire BP 576 64012 Pau France Tel: (33) 559407262 Fax: (33) 559407255 Email: [email protected] c. -

Latin America in Times of Global Environmental Change the Latin American Studies Book Series

The Latin American Studies Book Series Cristian Lorenzo Editor Latin America in Times of Global Environmental Change The Latin American Studies Book Series Series Editors Eustógio W. Correia Dantas, Departamento de Geografia, Centro de Ciências, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil Jorge Rabassa, Laboratorio de Geomorfología y Cuaternario, CADIC-CONICET, Ushuaia, Tierra de Fuego, Argentina Andrew Sluyter, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA [email protected] The Latin American Studies Book Series promotes quality scientific research focusing on Latin American countries. The series accepts disciplinary and interdisciplinary titles related to geographical, environmental, cultural, economic, political and urban research dedicated to Latin America. The series publishes comprehensive monographs, edited volumes and textbooks refereed by a region or country expert specialized in Latin American studies. The series aims to raise the profile of Latin American studies, showcasing important works developed focusing on the region. It is aimed at researchers, students, and everyone interested in Latin American topics. Submit a proposal: Proposals for the series will be considered by the Series Advisory Board. A book proposal form can be obtained from the Publisher, Juliana Pitanguy ([email protected]). More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15104 [email protected] Cristian Lorenzo Editor Latin America in Times of Global Environmental Change 123 [email protected] Editor Cristian Lorenzo Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas —Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas (CONICET) Instituto de Ciencias Polares, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales—Universidad Nacional de Tierra del Fuego Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina ISSN 2366-3421 ISSN 2366-343X (electronic) The Latin American Studies Book Series ISBN 978-3-030-24253-4 ISBN 978-3-030-24254-1 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24254-1 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

Diego Maradona 1960 -2020 a Qué Planeta Te Fuiste

www.elobservador.com.uy sábado 28 • domingo 29 • noviembre 2020 / Montevideo • Especial Diego Maradona 1960 -2020 A qué planeta te fuiste r El mundo conmovido por la muerte de Diego Armando Maradona a los 60 años; la vida dentro y fuera de la cancha del genio del fútbol mundial en esta edición especial de El Observador afp Fin de semana 2 Sábado 28 · domingo 29 · noviembre 2020 Diego Maradona 1960 -2020 afp a curarse de las drogas, de donde Ignacio Chans volvió peor. Su baipás gástrico @ignaciochans que lo hizo bajar 40 kilos y ser showman de televisión, otra vez eguramente la vida de Diego con una euforia que indicaba que Armando Maradona, falleci- algo no iba bien. Sdo este miércoles 25 a los 60 Con cada nueva recaída, la años, haya sido uno de los mayores persona Maradona iba desapare- realitiy shows de la historia mun- ciendo a manos de la caricatura. dial. Cuesta encontrar alguien de Su agudeza mental de las mejores quien todos los detalles de su vida, épocas (solo alguien muy inteligen- desde los más poéticos hasta los te podría haber logrado lo de él en más escabrosos, sean públicos. una cancha) iba desapareciendo, Ni siquiera la realeza europea, y apenas guardaría algunos capí- a quienes conocemos desde que tulos cuando dirigió a la selección nacen. No, de ellos conocemos lo argentina en 2009-2010. De genio que ellos quieren: se guardan en táctico nada, de motivador mucho, sus castillos y su vida es un pro- para esa etapa recordada por los medio entre sus lavados partes de “Que la sigan chupando”, “la tenés prensa y apariciones públicas, y las adentro” y el 4-0 de Alemania. -

The Locker-Room Librarian: the Maradona of Literature Dissemination

Date : 23/05/2008 The Locker-Room Librarian: The Maradona of literature dissemination Stig Elvis Furset Norwegian Archive Library and Museum Authority Oslo, Norway Meeting: 85. Literacy and Reading in co-operation with the Public Libraries and Library Services to Multicultural Populations Simultaneous Interpretation: Not available WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 74TH IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 10-14 August 2008, Québec, Canada http://www.ifla.org/iv/ifla74/index.htm ABSTRACT: What is the similarity between a book and a football? Given imagination, you can do tricks with both. What is the similarity between karate and promoting literature among young people? They are both martial arts. What is the similarity between a locker-room librarian and an athlete? They both aim for peak performance. For most libraries and librarians the school system has up to now provided the only avenue for promoting literature among children and young people. The project “Sport and Reading” is different, arising from the realisation that many youngsters spend much of their spare time training or playing for their local team or sports club and that this can provide an arena for the locker-librarian, the Diego Maradona of reading. The locker-librarian is part of a larger initiative aimed at sports in general, both top-class athletes and the everyday amateur. His or her task as a professional librarian is to promote literature by direct contact with youngsters in training throughout a wide range of sports and clubs. Each librarian and club is supplied with a bag of books, some 50 titles, to be loaned out, read and exchanged among the young members. -

Regional Issues on Firm Entry and Exit in Argentina: Core and Peripheral Regions

REGIONAL ISSUES ON FIRM ENTRY AND EXIT IN ARGENTINA: CORE AND PERIPHERAL REGIONS. Carla Daniela Calá Dipòsit Legal: T 1655-2014 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. -

Ultrapetrol Bahamas Ltd

ULTRAPETROL BAHAMAS LTD FORM 20-F (Annual and Transition Report (foreign private issuer)) Filed 03/17/09 for the Period Ending 12/31/08 Telephone 242-364-4755 CIK 0001062781 Symbol ULTR SIC Code 4412 - Deep Sea Foreign Transportation of Freight Industry Water Transportation Sector Transportation http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2009, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) [ ] REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) or (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR [ X ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 333-08878 OR [ ] SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report: N/A ULTRAPETROL (BAHAMAS) LIMITED (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Ultrapetrol (Bahamas) Limited H & J Corporate Services Ltd. Ocean Centre, Montagu Foreshore East Bay St. Nassau, Bahamas P.O. Box SS-19084 (Address of principal executive offices) Leonard J. Hoskinson. Tel.: 1 (242) 364-4755. E-mail: [email protected]. Address: Ocean Centre, Montagu Foreshore, East Bay St., P.O. Box SS-19084, Nassau, Bahamas. -

Australian Way June 2014

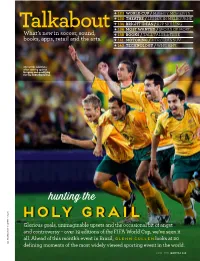

✈ 123 WORLD CUP / MIGHTY MOMENTS ✈ 130 THEATRE / LES MIS IN MELBOURNE ✈ 134 BRIGHT IDEAS / APP SKILLING Talkabout ✈ 136 MOST WANTED / SPOILS OF MORE What’s new in soccer, sound, ✈ 138 BOOKS / TALL TALES & TRUE books, apps, retail and the arts. ✈ 141 MOTORING / MERCEDES SUV ✈ 143 TECHNOLOGY / WI-FI HI-FI Socceroos celebrate after scoring against Uruguay and qualifying for the 2006 World Cup hunting the holyholy grailgrail Glorious goals, unimaginable upsets and the occasional bit of angst and controversy – over 19 editions of the FIFA World Cup, we’ve seen it all. Ahead of this month’s event in Brazil, GlenN Cullen looks at 20 ALL PHOTOGRAPHY: GETTY IMAGES defining moments of the most widely viewed sporting event in the world. JUNE 2014 QANTAS 123 Diego Maradona’s “Hand of God” goal The Lions of Cameroon, in 1986; Uruguay vs down to nine players, beat Argentina at the first defending champions World Cup (left) Argentina in 1990 #7 #9 1986 1990 #11 1994 Roberto Baggio (left) Diego Maradona misses a penalty and celebrates his second hands Brazil the 1994 goal against England in World Cup #1 1986 – this one scored 1930 with his boot 01 The game begins There were 93,000 people cheeky one-two with Giuseppe packed into Montevideo’s Giannini, Baggio slalomed through Estadio Centenario to see home the Czech defence, finally piercing side Uruguay get the ball rolling in two players and the keeper to the first World Cup final of 1930. score a silky goal. Much to the delight of the home nation, Uruguay beat Argentina 11 4-2 to clinch the title.