Lionel Messi and the Art of Living

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona

International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research (IJMSR) Volume 1, Issue 2 (July 2013), PP 45-49 www.arcjournals.org CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona Amanpreet Singh Chopra Phd. Research Scholar, UPES, India Abstract: Author studied the development program(s) and leadership succession planning strategies of FC Barcelona, one the most successful club in Spanish Football history and analyzed that success of club is deeply rooted in its strategies from grooming of homegrown talent at La Masia to the appointment of coaching staff. Taking cue from club strategies author identified 5 lessons for Corporate- Developing organizational belief in growth strategies, Developing young executive through structured T&D programs, Present career progression opportunities to young employees, Develop „inward‟ succession planning framework through grooming in-house talent and above all nurturing the philosophy of “Más que una empresa”(More than a company). Key Words: Succession Planning, Leadership Development, Sports Psychology 1. FC BARCELONA Futbol Club Barcelona also known as FC Barcelona and familiarly as Barça, is a professional football club, based in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Founded in 1899 by a group of Swiss, English and Catalan footballers led by Joan Gamper, the club has become a symbol of Catalan culture and Catalanism, hence the motto "Més que un club" (More than a club). It is the world's second-richest football club in terms of revenue, with an annual turnover of €398 million (2011). The unique feature of the club is that unlike many other football clubs, the supporters own and operate Barcelona. Jack Greenwell was the first fulltime club manager from 1917 to 1924 under which club grabbed 6 tournament honors. -

LEARNING from the BEST Gabriel Masfurroll

LEARNING FROM THE BEST Gabriel Masfurroll Foreword I first met Gabriel Masfurroll in the seventies, when he was a teenager and a competitive swimmer. At that time, swimming played a very important part in my life because the European Championships held in Barcelona in 1970, in which I participated actively, were an excellent yardstick for the Olympic Games of 1992. Masfurroll was living in the Residencia Joaquín Blume in Barcelona, run by my friend Ricardo Sánchez, and we had good friends in common such as Santiago Esteva and Maria Paz Corominas, swimmers who in their day were key figures in Spanish sport. I shall never forget something ‘Gaby’, as his friends call him, said to me when he was still very young: “Mr. Samaranch, when I grow up I want to be like you and match your achievements. I also love sport and believe I can do a lot for it”. It comes as no surprise to me, then, to see Masfurroll holding positions of responsibility in leading sporting institutions. A few years later, I met up with “Gaby” again when he was head of the Quirón Clinic in Barcelona. Since then we have kept in touch on a regular basis. We have met and written to each other on numerous occasions and I recall a beautiful picture, on display at the headquarters of the Olympic Committee in Lausanne, which he gave me on one of his visits. I have followed his career very closely over these years and that phrase “when I grow up I want to be like you”, made me take a keen interest in both his personal and professional development. -

Fis Hm an Pele, Lio Nel Messi, and More

FISHMAN PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PELE, LIONEL MESSI, AND MORE JON M. FISHMAN Lerner Publications Minneapolis SCORE BIG with sports fans, reluctant readers, and report writers! Lerner Sports is a database of high-interest LERNER SPORTS FEATURES: biographies profiling notable sports superstars. Keyword search Packed with fascinating facts, these bios Topic navigation menus explore the backgrounds, career-defining Fast facts moments, and everyday lives of popular Related bio suggestions to encourage more reading athletes. Lerner Sports is perfect for young Admin view of reader statistics readers developing research skills or looking Fresh content updated regularly for exciting sports content. and more! Visit LernerSports.com for a free trial! MK966-0818 (Lerner Sports Ad).indd 1 11/27/18 1:32 PM Copyright © 2020 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Lerner Publications Company A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com. Main body text set in Aptifer Sans LT Pro. Typeface provided by Linotype AG. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fishman, Jon M., author. Title: Soccer’s G.O.A.T. : Pele, Lionel Messi, and more / Jon M. -

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101875/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Anderson, Christopher J., Arrondel, Luc, Blais, André, Daoust, Jean François, Laslier, Jean François and Van Der Straeten, Karine (2019) Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world. Perspectives on Politics. ISSN 1537-5927 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719002391 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections: Voting For the Best Soccer Player in the World Christopher J. Anderson London School of Economics and Political Science Luc Arrondel Paris School of Economics André Blais University of Montréal Jean-François Daoust McGill University Jean-François Laslier Paris School of Economics Karine Van der Straeten Toulouse School of Economics Abstract It is widely assumed that celebrities are imbued with political capital and the power to move opinion. To understand the sources of that capital in the specific domain of sports celebrity, we investigate the popularity of global soccer superstars. -

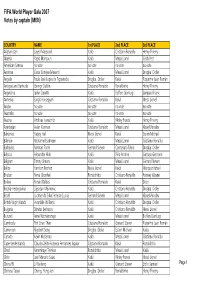

Final MEN by Coach and Captain

FIFA World Player Gala 2007 Votes by captain (MEN) COUNTRY NAME 1st PLACE 2nd PLACE 3rd PLACE Afghanistan Sayed Maqsood Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Henry Thierry Algeria Yazid Mansouri Kaká Messi Lionel Cech Petr American Samoa no vote no vote no vote no vote Andorra Óscar Sonejee Masand Kaká Messi Lionel Drogba Didier Angola Paulo José Lopes de Figueiredo Drogba Didier Kaká Riquelme Juan Román Antigua and Barbuda George Dublin Cristiano Ronaldo Ronaldinho Henry Thierry Argentina Javier Zanetti Kaká Buffon Gianluigi Lampard Frank Armenia Sargis Hovsepyan Cristiano Ronaldo Kaká Messi Lionel Aruba no vote no vote no vote no vote Australia no vote no vote no vote no vote Austria Andreas Ivanschitz Kaká Ribéry Franck Henry Thierry Azerbaijan Aslan Karimov Cristiano Ronaldo Messi Lionel Klose Miroslav Bahamas Happy Hall Messi Lionel Kaká Essien Michael Bahrain Mohamed Salmeen Kaká Messi Lionel Cristiano Ronaldo Barbados Norman Forde Gerrard Steven Cannavaro Fabio Drogba Didier Belarus Alexander Hleb Kaká Pirlo Andrea Gattuso Gennaro Belgium Timmy Simons Kaká Messi Lionel Gerrard Steven Belize Harrison Rochez Messi Lionel Kaká Márquez Rafael Bhutan Pema Chophel Ronaldinho Cristiano Ronaldo Rooney Wayne Bolivia Ronald Baldes Cristiano Ronaldo Kaká Deco Bosnia-Herzegovina Zvjezdan Misimovic Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Drogba Didier Brazil Lucimar da Silva Ferreira (Lucio) Gerrard Steven Messi Lionel Klose Miroslav British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Drogba Didier Bulgaria Dimitar Berbatov Kaká Cristiano Ronaldo Messi Lionel Burundi -

Media Value in Football Season 2014/15

MERIT report on Media Value in Football Season 2014/15 Summary - Main results Authors: Pedro García del Barrio Director Académico de MERIT social value Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) Bruno Montoro Ferreiro Analista de MERIT social value Asier López de Foronda López Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) With the collaboration of: Josep Maria Espina Serra (UIC Barcelona) Arnau Raventós Gascón (UIC Barcelona) Ignacio Fernández Ponsin (UIC Barcelona) www.meritsocialvalue.com 2 Presentation MERIT (Methodology for the Evaluation and Rating of Intangible Talent) is part of an academic project with vast applications in the field of business and company management. This methodology has proved to be useful in measuring the economic value of intangible talent in professional sport and in other entertainment industries. In our estimations – and in the elaboration of the rankings – two elements are taken into consideration: popularity (degree of interest aroused between the fans and the general public) and media value (the level of attention that the mass media pays). The calculations may be made at specific points in time during a season, or accumulating the news generated during a particular period: weeks, months, years, etc. Additionally, the homogeneity amongst the measurements allows for a comparison of the media value status of individuals, teams, institutions, etc. Together with the measurements and rankings, our database allows us to conduct analyses on a wide variety of economic and business problems: estimates of the market value (or “fair value”) of players’ transfer fees; calculation of the brand value of individuals, teams and leagues; valuation of the economic return from alliances between sponsors; image rights contracts of athletes and teams; and a great deal more. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

A Novel Application of Fuzzy Set Theory and Topic Model in Sentence Extraction for Vietnamese Text

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.10 No.8, August 2010 41 A Novel Application of Fuzzy Set Theory and Topic Model in Sentence Extraction for Vietnamese Text Ha Nguyen Thi Thu 1† and Nguyen Thien Luan2††, †Department of Computer Science, Electric Power University ,235 Hoang Quoc Viet, Ha noi, Viet Nam ††Faculty of Information Technology, Le Qui Don Technical University,100 Hoang Quoc Viet, Ha Noi, Viet Nam Summary on the method of calculating the frequency of words in Vietnamese language has common characteristics with some sentences is not appropriate . On the other hand, study on Asian languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean ... They do Vietnamese text summary is now something new, corpus not define words based on spaces. In this article, we present a for Vietnamese text summarization or word segmentation method that application of Fuzzy set theory and topic model to is still limited. extract sentences in Vietnamese texts which have been categorized by topic. This method based on identification of important features as : length of sentence, weight of terms in We studied Vietnamese text that categorized by topic and sentences, position of sentences ..., then extracting important found that with each different theme, weight of words sentences according to the ratio, this ratio indicate which (hereafter called terms) would depend on the different sentences in original text will be extracted. We also built a topics. Therefore, we have built sets of terms for each system based on this method and experiments have obtained topic and applied Fuzzy theory in determining degree of good results, satisfying the given requirements. -

Goal Celebrations When the Players Makes the Show

Goal celebrations When the players makes the show Diego Maradona rushing the camera with the face of a madman, José Mourinho performing an endless slide on his knees, Roger Milla dancing with the corner flag, three Brazilians cradling an imaginary baby, Robbie Fowler sniffing the white line, Cantona, a finger to his lips contemplating his incredible talent... Discover the most fantastic ways to celebrate a goal. Funny, provo- cative, pretentious, imaginative, catch football players in every condition. KEY SELLING POINTS • An offbeat treatment of football • A release date during the Euro 2016 • Surprising and entertaining • A well-known author on the subject • An attractive price THE AUTHOR Mathieu Le Maux Mathieu Le Maux is head sports writer at GQ magazine. He regularly contributes to BeInSport. His key discipline is football. SPECIFICATIONS Format 150 x 190 mm or 170 x 212 mm Number of pages 176 pp Approx. 18,000 words Price 15/20 € Release spring 2016 All rights available except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com contENTS The Hall of Fame Goal celebrations from the football legends of the past to the great stars of the moment: Pele, Eric Cantona, Diego Maradona, George Best, Eusebio, Johan Cruijff, Michel Platini, David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Drogba, Ronaldo, Messi, Thierry Henry, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Balotelli, Zlatan, Neymar, Yekini, Paul Gascoigne, Roger Milla, Tardelli... Total Freaks The wildest, craziest, most unusual, most spectacular goal celebrations: Robbie Fowler, Maradona/Caniggia, Neville/Scholes, Totti selfie, Cavani, Lucarelli, the team of Senegal, Adebayor, Rooney Craig Bellamy, the staging of Icelanders FC Stjarnan, the stupid injuries of Paolo Diogo, Martin Palermo or Denilson.. -

FURTI INTER– 100 DI GRANDE ONESTA’ Timbro Bianconero

FURTI INTER– 100 DI GRANDE ONESTA’ Timbro Bianconero 1. Furto del primo scudetto nel 1910 (Pro Vercelli costretta dall'Inter a giocare coi bambini, in un ineguagliato esempio di totale mancanza di sportività). Nel 1910 successe che la Federazione (casualmente...) scelse, in prima istanza, una data per la finale scudetto Pro Vercelli-Inter. Guarda caso in quella data tutta la squadra titolare della Pro Vercelli era già impegnata con la Nazionale Militare. La Pro Vercelli chiese quindi ovviamente lo spostamento della finale scudetto. La Federazione rispose che a loro andava bene se anche l'Inter avesse accettato. L'Inter, scandalosamente, RISPOSE DI NO e la Federazione non esitò a mantenere la data stabilita, del tutto inadeguata. La Pro Vercelli, giustamente indignata per questo gesto vergognoso, mandò in campo la 4^ squadra (i bambini di 11 anni!!!!). L'Inter vinse la partita 10-3 (riuscendo però a prendere 3 gol dai bambini!!) e vinse in questo modo il suo primo scudetto. Tra il primo e l'ultimo cambiano i metodi, non cambiano le furbate. 2. Salvezza(A TAVOLINO) comprata nel 1922, dopo una retrocessione sul campo; Nel 1922 l'Inter arriva ultima, meno punti di tutti, meno gol fatti e più gol subiti. A fine campionato si decide che invece di far salire le squadre che ne hanno diritto bisogna fare i play-out. Non basta. All'Inter viene data come avversario l'Alta Italia, squadra però già fallita da settimane, per cui vince gli scontri diretti a tavolino! 3. 1961 SCARSA SPORTIVITA’ Nel 1961 l’Inter protesta perchè la partita Juve-Inter viene fatta ripetere anzichè essere assegnata all’Inter a tavolino per sfondamento delle recinzioni del pubblico che stava troppo stretto e si era portato a bordo campo. -

P20 Layout 1

Lydia Ko wins Marsh powers LPGA Tour’s NW Aussies to Arkansas Tri-Nation victory 16Championship 17 TUESDAY, JUNE 28, 2016 PSG part company with Blanc amid Emery talk Page 18 EAST RUTHERFORD: Chile’s players pose with the trophy after winning the Copa America Centenario final by defeating Argentina in the penalty shoot-out in East Rutherford, New Jersey, United States, on Sunday. —AFP Chile stun Argentina to win Copa Messi exit leaves Argentinian football in turmoil EAST RUTHERFORD: Lionel Messi put his penalty kick a final for the third year in a row and the fourth time over- Francisco Silva converted the shootout finale for the Nicolas Castillo and Charles Aranguiz converted their Brazilian referee Heber Lopes became the focus in over the crossbar, grabbed his shirt, clenched his teeth all with Argentina. There was also the 2007 Copa final fifth-ranked La Roja after goalkeeper Claudio Bravo - kicks for Chile, and Javier Mascherano and Sergio Aguero the first half, ejecting a pair of defenders: Chile’s Marcelo and covered his face with both hands. A few minutes lat- against Brazil, when he was still a wunderkind, and then Messi’s Barcelona teammate - made a diving stop on made theirs, leaving the teams tied 2-2 after three Diaz in the 28th minute and Argentina’s Marcos Rojo in er he walked off the field, a dazed, pained look on his an extra-time loss to Germany in the 2014 World Cup. Lucas Biglia’s attempt. On an ill-tempered evening that rounds. Jean Beausejour put Chile ahead, and Bravo the 43rd.