Winter 2017 in Publisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Draft Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3, Appendices J Through N

United States Department of Agriculture Santa Fe National Forest Draft Land Management Plan Draft Environmental Impact Statement Rio Arriba, San Miguel, Sandoval, Santa Fe, Mora, and Los Alamos Counties, New Mexico Volume 3, Appendices J through N Forest Santa Fe Southwestern Region MB-R3-10-29 Service National Forest June 2019 Cover photo: Reflection of mountain peak and forest in Nambe Lake. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Tres Arroyos Del Poniente Community Plan

1 Welcome! •This is an open house. •Please sign in and get a name tag. •We invite youview to all walk the aroundposters. and •We are hereregarding to answer the any process, questions the drafts and the anticipated outcomes. •Please feelto free the toposters. add any comments Tres Arroyos Santa Fe County •Please discusscomments any questions with your or neighbors and Community Planning Area County staff. Legend Tres Arroyos Community Planning Area Minor Roads Parcels Major Roads •Grab a drink and some snacks. Roads Intermittent Perennial Rivers and Streams R E I X I S T O A I T P LI Y E A D L E R L L L A N NOP C A A E K M RE LL C K O C MB CA C U TA A B NO E P ONI N I RA T TIER B Department O LA S MIN CA E A N EXI D L Santa Fe County 9 E N RUT A 59 LL S I O T D CA A NM R A T L V PA A R O N O O E O Planning Division S Growth Management PA N C I E M A C ALL T NO CARLOS RAEL C CAMI XI E 9 9 5 M N US NA FERG ON LN MONTOYA PL June 23, 2015 A A N LE CARMILI T CAL A CAMINO I CARLOS RAEL L A E L D M N R I A T L E N ALAMO RD E L O L LL Y A N CA CAMINO MIO C A FAMILY LN ST ST GA C LLEGO S LN A E LN N DA U IX E L N SI B M T O A C R AL NYON VISTA MAEZ RD A W AEZ C O E D M U A LA CIENEGUITA L M B E TERO U O EY S S R Q RLO O CERRO LINDO BL O C E CA tres_arroyos_community_planning_ R CAMIN E ALLE I U ANGE O L L P IN A AMIN C C L A R E CORIAN DER RD C CAMINO TRES ARROYOS area_boundary_6_23_15_poster.mxd W BLUE CANYON WAY O BOYLAN LN L F HARRISON RD E MUSCLE CAR LN TA T A CAMINO DON EMILIO JORGENSEN LN BOYLAN CI JUN L R CALLE A D O DE COMER R LUG AR DE -

Santa Fe Solid Waste Management Agency

SANTA FE SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT AGENCY REQUEST FOR BIDS BID NO. ‘16/07/B CONTRACT DOCUMENTS AND SPECIFICATIONS FOR CAJA DEL RIO LANDFILL PHASE 2 – LANDFILL GAS COLLECTION SYSTEM AUGUST 2015 BIDS DUE: SEPTEMBER 25, 2015 at 2:00 P.M. PURCHASING OFFICE CITY OF SANTA FE 2651 SIRINGO ROAD – BUILDING “H” SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO 87505 Caja del Rio Landfill Phase 2 – Landfill Gas Collection System CAJA DEL RIO LANDFILL PHASE 2 – LANDFILL GAS COLLECTION SYSTEM BID NO. ‘16/07/B TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTRACT DOCUMENTS Section Title Section - Page 1. Advertisement for Bid...................................................................................................... 1-1 2. Instructions to Bidders ..................................................................................................... 2-1 3. Bid Proposal ..................................................................................................................... 3-1 4. Bid Form .......................................................................................................................... 4-1 5. Bid Bond .......................................................................................................................... 5-1 6. Supplementary Bid Forms ............................................................................................... 6-1 7. Agreement Between Owner and Contractor .................................................................... 7-1 8. Performance Bond .......................................................................................................... -

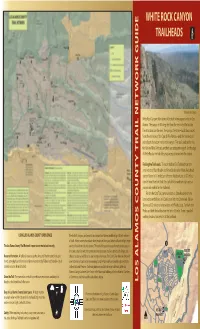

F White Rock Canyon Trailheads Los Alamos Count Y Tr Ail Net W Ork Guide

and head to the cul-du-sac. Pick up the South Bench Trail at the end of the street and head down into Acid Canyon. Pass a short bridge to the right and continue straight through the rocks along the trail. Near the large Acid Canyon Bridge, angle right, cross the bridge, and retrace your steps back to the trailhead. WHITE ROCK CANYON TRAILHEADS F White Rock Canyon White Rock Canyon offers some of the best hiking opportunities in Los Alamos. The canyon is 900 deep feet from the rim to the Rio Grande. The attractions are the river, the springs, the rocks—basalt lavas oozed from the volcanoes of the Caja del Rio Plateau—and the hundreds of petroglyphs that adorn rocks in the canyon. Two trails lead to the river, the Red and Blue Dot trails, and both are steep and rugged. On the edge of White Rock a rim trail offers easy access to views into the canyon. Finding the Trailheads: To reach the Blue Dot Trailhead from the intersection of State Road 4 and Rover Boulevard in White Rock, head east on Rover. In 0.1 miles, turn left onto Meadow Lane. In 0.7 miles, turn left into Overlook Park. Pass by ball fields and turn right onto a paved road marked for the trailhead. For the Red Dot Trail, continue south on State Road 4 from the intersection with Rover. In 0.2 mile, turn left onto Sherwood. Follow Sherwood 0.5 mile to a t-intersection with Piedra Loop. Turn left onto Piedra and find the trailhead on the left in 0.6 mile. -

Npdes Permit No

NPDES PERMIT NO. NM0030848 FACT SHEET FOR THE DRAFT NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM (NPDES) PERMIT TO DISCHARGE TO WATERS OF THE UNITED STATES APPLICANT City of Santa Fe Buckman Direct Diversion 341 Caja del Rio Road Santa Fe, NM 87506 ISSUING OFFICE U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 6 1201 Elm Street, Suite 500 Dallas, TX 75270 PREPARED BY Ruben Alayon-Gonzalez Environmental Engineer Permitting Section (WDPE) Water Division VOICE: 214-665-2718 EMAIL: [email protected] DATE PREPARED May 29, 2019 PERMIT ACTION Proposed reissuance of the current NPDES permit issued July 29, 2014, with an effective date of September 1, 2014, and an expiration date of August 31, 2019. RECEIVING WATER – BASIN Rio Grande Permit No. NM0030848 Fact Sheet Page 2 of 16 DOCUMENT ABBREVIATIONS In the document that follows, various abbreviations are used. They are as follows: 4Q3 Lowest four-day average flow rate expected to occur once every three years BAT Best available technology economically achievable BCT Best conventional pollutant control technology BPT Best practicable control technology currently available BMP Best management plan BOD Biochemical oxygen demand (five-day unless noted otherwise) BPJ Best professional judgment CBOD Carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand (five-day unless noted otherwise) CD Critical dilution CFR Code of Federal Regulations Cfs Cubic feet per second COD Chemical oxygen demand COE United States Corp of Engineers CWA Clean Water Act DMR Discharge monitoring report ELG Effluent limitations guidelines -

Chapter 4: Geographic Areas Places Matter

Chapter 4: Geographic Areas Places Matter. Across the 1.6 million acres of the Santa Fe National Forest (NF), there are diverse communities and cultures, recreation uses, and restoration needs. Compared to other National Forests, the Santa Fe NF is surrounded by very diverse landscapes as well as unusually diverse communities and cultures with roots going back hundreds and thousands of years. Nationwide not all Forest Plans use Geographic Areas (GAs), but to recognize and best manage the similarities and differences that exist across distinct landscapes on the Santa Fe NF, seven GAs have been identified. Each of the seven GAs on the Forest have different restoration needs, sustainable recreation opportunities, connections to nearby communities, and partnerships with the public. Each GA is described in the context of local communities, uses, and restoration needs. In addition, each GA is accompanied by Desired Conditions that refine broad forest-wide management direction and offer unique guidance. From West to East, the 7 Geographic Areas are: • Canadas and Nacimiento • Jemez Mesas and Canyons • North Jemez Mountains • West Sangres and Caja • Pecos River Canyon • East Sangres • Rowe Mesa and Anton Chico Geographic Areas are made up of the unique cultural identities, ecology, and types of use specific to different places on the Forest. These features may align with Ranger Districts, county lines, watersheds, or other geographical and socioeconomic boundaries. Where people travel from as they access different parts of the forest was also considered in defining boundaries. Therefore, GAs can also represent many small “community” forests within the larger Santa Fe NF. Local community culture, economic drivers, natural and man-made landscape features, ecology, types of recreation, and restoration needs shaped the GAs, which are delineated by easily recognized natural features and infrastructure (e.g., waterways, roads, and ridges). -

Caja Del Rio – New Mexico

Caja del Rio – New Mexico AERC Trails Grant, completed 2008 A local spot to ride for AERC member Deirdre Monroe turned into a calling – to turn neglected trails into a prime riding spot by Marsha Hayes (2015) Did a $5,000 AERC trails grant in 2007 pay off? What is happening in northern New Mexico’s Caja del Rio? The Caja del Rio is a spectacular 100,000-acre expanse of public land west of Santa Fe, New Mexico. When it comes time to update status on something formed about 30 million years ago, it becomes imperative to narrow the update, sparing everyone a required geology degree and a lifetime of reading. Fast forward through the volcanos and the plate formation, and examine the forces AERC member Deirdre Monroe has set in motion since she first rode the area in 1995. And after this examination, decide: did a $5,000 AERC grant in 2007 reap the expected benefits? When Monroe first rode the Caja in 1995, she was not looking for project. She sought solitude and an environment that encouraged introspection. The Caja filled her needs and satisfied her soul. To give a non-horse person perspective, a mountain- biking webpage describes the area as “a huge and desolate collection of old volcanos, wells, horse traps, and other remnants of the old west . .” The Caja triggered something in Monroe. “I’ve drawn strength from the rides I’ve taken there. Finding the Caja was a happy accident in my life,” Monroe explained. She fell in love with the land’s colors, scents, views, and mysteries. -

Bandelier National Monument: Natural Resource Condition Assessment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Bandelier National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/BAND/NRR—2015/1000 ON THIS PAGE View of Upper Alamo Canyon, 2009 Photography by: National Park Service ON THE COVER View across Burnt Mesa, Bandelier National Monument Photography by: Dale Coker Bandelier National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/BAND/NRR—2015/1000 Editors Brian Jacobs1 Barbara Judy1 Stephen Fettig1 Kay Beeley1 Collin Haffey2 Catherin Schwemm3 Jean Palumbo4 Lisa Thomas4 1Bandelier National Monument 15 Entrance Road Los Alamos, NM 87544 2 Jemez Mountain Field Station, USGS at Bandelier National Monument 15 Entrance Road Los Alamos, NM 87544 3Institute for Wildlife Studies P.O. Box 1104 Arcata, CA 955184 4Southern Colorado Plateau Network National Park Service USGS Flagstaff Science Center 2255N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 August 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science offi ce in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and oth- ers in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision- making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

Program and Abstracts

PROGRAM & ABSTRACTS NEW MEXICO ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY 46TH ANNUAL MEETING AND NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF GAME & FISH/NMOS GRAY VIREO SYMPOSIUM 12 April 2008 Albuquerque, New Mexico NEW MEXICO ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY 46TH ANNUAL MEETING AND NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF GAME & FISH/NMOS GRAY VIREO SYMPOSIUM 12 April 2008 Albuquerque, New Mexico 8:30 - 9:00 a.m. REGISTRATION 9:00 a.m. Morning refreshments available 9:00 - 9:30 NMOS BUSINESS MEETING – Welcome – Minutes – Treasurer’s Report – Old Business – New Business – Election of Officers – Committee Reports – NMOS Web Site (www.nmbirds.org) – Rare Bird Alert/Hotline – NMOS Field Notes Database – NMOS Bulletin – NMOS Field Notes – Next Year’s Meeting – Future Plans – Meeting Announcements/Housekeeping 9:30 - 9:45 NMOS Greeting – Roland Shook (NMOS President) 9:45 - 12:00 NMDGF/NMOS GRAY VIREO SYMPOSIUM – Hira Walker (NMDGF), Session Chair 9:45 - 10:00 NMDGF Greeting and Introduction to Symposium – Lee Pierce (NMDGF) 10:00 - 10:20 Gray Vireo Status and Distribution on Fort Bliss: 2007 – Charles Britt* (NMSU) and Carl Lundblad (Amargosa Valley, NV) 1 10:20 - 10:40 Habitat Perseverance and Status of Gray Vireos on Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, NM – Carol Finley* (Kirtland AFB), and Robert Frei (Clover Leaf Environmental Solutions, Inc.) 10:40 - 11:00 Gray Vireo Monitoring in Northwestern and Southeastern New Mexico – Mike Stake* and Gail Garber (Hawks Aloft) 11:00 - 11:20 Density and Habitat Use of Gray Vireos in the San Juan Basin Natural Gas Field in Northwestern New Mexico – Lynn Wickersham* and John L. Wickersham (Ecosphere Environmental Services) 11:20 - 11:40 Modeling Gray Vireo Habitat – General Considerations – Paul Arbetan* and Teri Neville* (Natural Heritage New Mexico) 11:40 - 12:00 Symposium Conclusions – Hira Walker (NMDGF) 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. -

El Camino Real De Tierra Adentro Archival Study

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Prepared for: The New Mexico Spaceport Authority (NMSA) Las Cruces and Truth or Consequences, New Mexico The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Office of Commercial Space Transportation Compiled by: Jemez Mountains Research Center, LLC Santa Fe, New Mexico Contributors: Kristen Reynolds, Elizabeth A. Oster, Michael L. Elliott, David Reynolds, Maby Medrano Enríquez, and José Luis Punzo Díaz December, 2020 El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Statement of Purpose .................................................................................................. 1 • Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 • Scope and Organization ....................................................................................................................... 2 • El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro: Terminology and Nomenclature ............................... 4 2. History of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro; National Historic Trail Status........................... 6 3. A Guide to Sources of Information for El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro .............................. 16 • 3.1. Archives and Repositories .......................................................................................................