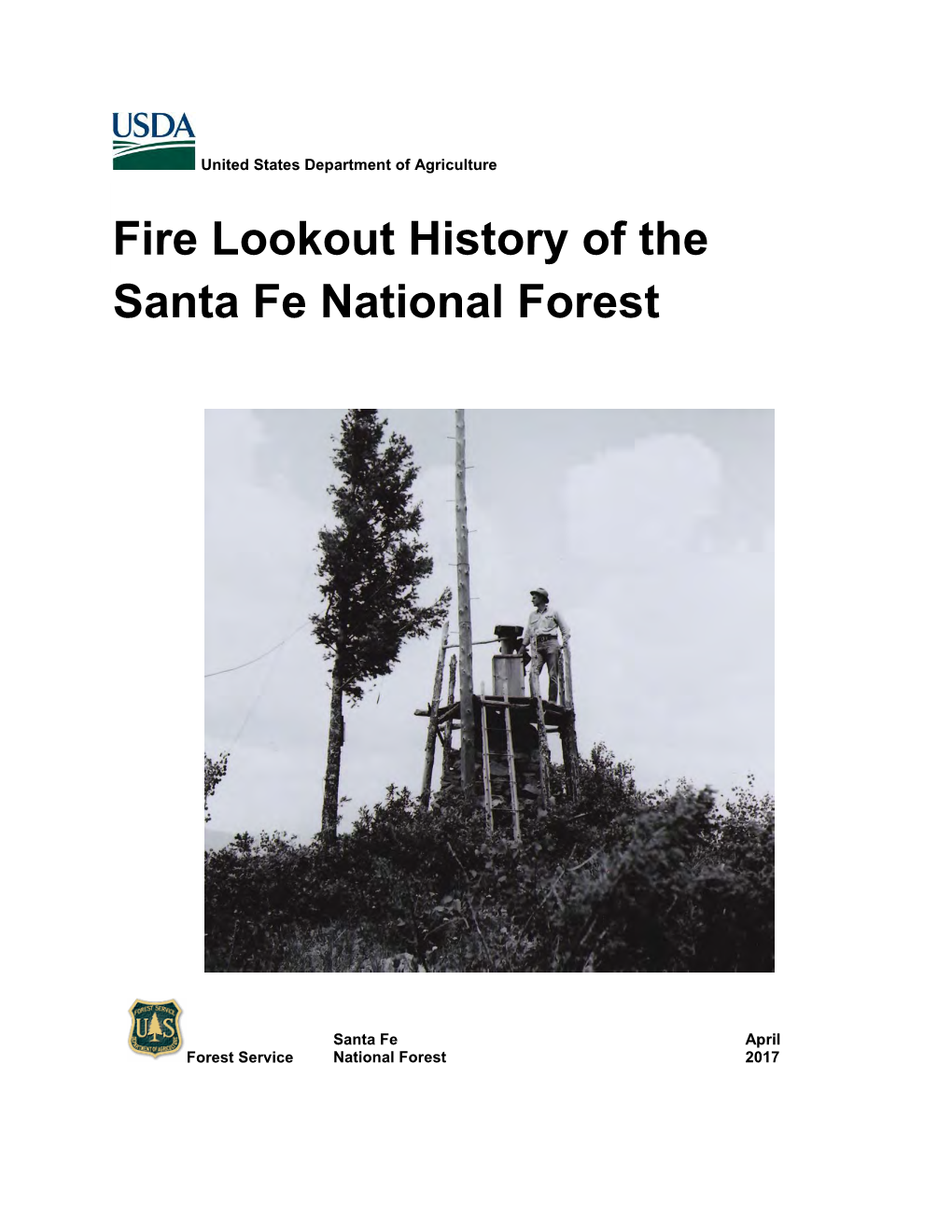

Fire Lookout History of the Santa Fe National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baylor Geological Studies

BAYLORGEOLOGICA L STUDIES PAUL N. DOLLIVER Creative thinking is more important than elaborate FRANK PH.D. PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY BAYLOR UNIVERSITY 1929-1934 Objectives of Geological Training at Baylor The training of a geologist in a university covers but a few years; his education continues throughout his active life. The purposes of train ing geologists at Baylor University are to provide a sound basis of understanding and to foster a truly geological point of view, both of which are essential for continued professional growth. The staff considers geology to be unique among sciences since it is primarily a field science. All geologic research in cluding that done in laboratories must be firmly supported by field observations. The student is encouraged to develop an inquiring ob jective attitude and to examine critically all geological concepts and principles. The development of a mature and professional attitude toward geology and geological research is a principal concern of the department. Frontis. Sunset over the Canadian River from near the abandoned settlement of Old Tascosa, Texas. The rampart-like cliffs on the horizon first inspired the name "Llano Estacado" (Palisaded Plain) among Coronado's men. THE BAYLOR UNIVERSITY PRESS WACO, TEXAS BAYLOR GEOLOGICAL STUDIES BULLETIN NO. 42 Cenozoic Evolution of the Canadian River Basin Paul N. DoUiver BAYLOR UNIVERSITY Department of Geology Waco, Texas Spring 1984 Baylor Geological Studies EDITORIAL STAFF Jean M. Spencer Jenness, M.S., Editor environmental and medical geology O. T. Ph.D., Advisor, Cartographic Editor what have you Peter M. Allen, Ph.D. urban and environmental geology, hydrology Harold H. Beaver, Ph.D. -

The Middle Rio Grande Basin: Historical Descriptions and Reconstruction

CHAPTER 4 THE MIDDLE RIO GRANDE BASIN: HISTORICAL DESCRIPTIONS AND RECONSTRUCTION This chapter provides an overview of the historical con- The main two basins are flanked by fault-block moun- ditions of the Middle Rio Grande Basin, with emphasis tains, such as the Sandias (Fig. 40), or volcanic uplifts, on the main stem of the river and its major tributaries in such as the Jemez, volcanic flow fields, and gravelly high the study region, including the Santa Fe River, Galisteo terraces of the ancestral Rio Grande, which began to flow Creek, Jemez River, Las Huertas Creek, Rio Puerco, and about 5 million years ago. Besides the mountains, other Rio Salado (Fig. 40). A general reconstruction of hydro- upland landforms include plateaus, mesas, canyons, pied- logical and geomorphological conditions of the Rio monts (regionally known as bajadas), volcanic plugs or Grande and major tributaries, based primarily on first- necks, and calderas (Hawley 1986: 23–26). Major rocks in hand, historical descriptions, is presented. More detailed these uplands include Precambrian granites; Paleozoic data on the historic hydrology-geomorphology of the Rio limestones, sandstones, and shales; and Cenozoic basalts. Grande and major tributaries are presented in Chapter 5. The rift has filled primarily with alluvial and fluvial sedi- Historic plant communities, and their dominant spe- ments weathered from rock formations along the main cies, are also discussed. Fauna present in the late prehis- and tributary watersheds. Much more recently, aeolian toric and historic periods is documented by archeological materials from abused land surfaces have been and are remains of bones from archeological sites, images of being deposited on the floodplain of the river. -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Borrador Preliminar Del Plan De Gestion De Recursos Y De La Tierra Propuesto

Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos Borrador preliminar del plan de gestión de recursos y de la tierra propuesto para el Bosque Nacional de Carson [Versión 2] Condados de Río Arriba, Taos, Mora y Colfax en Nuevo México Región Sur del Servicio Forestal Publicación Nro. Diciembre de 2017 De acuerdo con la ley federal de los derechos civiles y con los reglamentos y políticas de derechos civiles del Departamento de Agricultura de los Estados Unidos (USDA), el USDA, sus agencias, oficinas y empleados, y las instituciones que participen o administren los programas del USDA tienen prohibido cualquier tipo de discriminación por raza, color, origen nacional, religión, sexo, identidad de género (incluida la expresión de género), orientación sexual, discapacidad, edad, estado civil, estado familiar/parental, ingresos derivados de un programa de asistencia pública, creencias políticas, represalia o acto de venganza por actividad previa a los derechos civiles, en cualquiera de los programas o actividades realizadas o financiadas por el USDA (no todos los fundamentos son aplicables a todos los programas). Los plazos para la presentación de recursos y quejas varían según el programa o el incidente. Las personas con discapacidades que requieran de medios de comunicación alternativos para obtener información sobre el programa (p. ej., Braille, caracteres grandes, cintas de audio, lenguaje estadounidense de señas, etc.) deben contactar a la agencia responsable o al TARGET Center del USDA al (202) 720-2600 (voz y TTY), o ponerse en contacto con el USDA a través del Servicio Federal de Transmisiones al (800) 877-8339. Asimismo, la información de los programas puede estar disponible en otros idiomas además del inglés. -

Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

-» Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico By R. A. BAILEY, R. L. SMITH, and C. S. ROSS CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY » GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1274-P New Stratigraphic names and revisions in nomenclature of upper Tertiary and , Quaternary volcanic rocks in the Jemez Mountains UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1969 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract.._..._________-...______.._-.._._____.. PI Introduction. -_-________.._.____-_------___-_______------_-_---_-_ 1 General relations._____-___________--_--___-__--_-___-----___---__. 2 Keres Group..__________________--------_-___-_------------_------ 2 Canovas Canyon Rhyolite..__-__-_---_________---___-____-_--__ 5 Paliza Canyon Formation.___-_________-__-_-__-__-_-_______--- 6 Bearhead Rhyolite-___________________________________________ 8 Cochiti Formation.._______________________________________________ 8 Polvadera Group..______________-__-_------________--_-______---__ 10 Lobato Basalt______________________________________________ 10 Tschicoma Formation_______-__-_-____---_-__-______-______-- 11 El Rechuelos Rhyolite--_____---------_--------------_-_------- 11 Puye Formation_________________------___________-_--______-.__- 12 Tewa Group__._...._.______........___._.___.____......___...__ 12 Bandelier Tuff.______________.______________... 13 Tsankawi Pumice Bed._____________________________________ 14 Valles Rhyolite______.__-___---_____________.________..__ 15 Deer Canyon Member.______-_____-__.____--_--___-__-____ 15 Redondo Creek Member.__________________________________ 15 Valle Grande Member____-__-_--___-___--_-____-___-._-.__ 16 Battleship Rock Member...______________________________ 17 El Cajete Member____..._____________________ 17 Banco Bonito Member.___-_--_---_-_----_---_----._____--- 18 References . -

Geothermal Hydrology of Valles Caldera and the Southwestern Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO By Frank W. Trainer, Robert J. Rogers, and Michael L. Sorey U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER Albuquerque, New Mexico 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 5338 Montgomery NE, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Albuquerque, NM 87109-1311 Information regarding research and data-collection programs of the U.S. Geological Survey is available on the Internet via the World Wide Web. You may connect to the Home Page for the New Mexico District Office using the URL: http://nm.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................ 2 Purpose and scope........................................................................................................................ -

New Mexico Geological Society Spring Meeting Abstracts

the surface water system. Snow melt in the high VOLCANIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE WEST- mountains recharges shallow perched aquifers ERN SIERRA BLANCA VOLCANIC FIELD, Abstracts that discharge at springs that feed streams and SOUTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO, S. A. Kel- ponds where evaporation occurs. Water in ponds ley, [email protected], and D. J. Koning, and streams may then recharge another shallow New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral perched aquifer, which again may discharge at a Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and spring at a lower elevation. This cycle may occur Technology, Socorro, New Mexico 87801; K. A. New Mexico Geological Society several times until the water is deep enough to be Kempter, 2623 Via Caballero del Norte, Santa Fe, spring meeting isolated from the surface water system. A deeper New Mexico 87505; K. E. Zeigler, Zeigler Geo- regional aquifer may exist in this area. East of logic Consulting, Albuquerque, New Mexico The New Mexico Geological Society annual Mayhill along the Pecos Slope, regional ground 87123; L. Peters, New Mexico Bureau of Geology spring meeting was held on April 16, 2010, at the water flow is dominantly to the east toward the and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, New Mex- Macey Center, New Mexico Tech, Socorro. Fol- Roswell Artesian Basin. Some ground water also ico 87801; and F. Goff, Department of Earth and lowing are the abstracts from all sessions given flows to the southeast toward the Salt Basin and to the west into the Tularosa Basin. Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, at that meeting. -

Draft Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3, Appendices J Through N

United States Department of Agriculture Santa Fe National Forest Draft Land Management Plan Draft Environmental Impact Statement Rio Arriba, San Miguel, Sandoval, Santa Fe, Mora, and Los Alamos Counties, New Mexico Volume 3, Appendices J through N Forest Santa Fe Southwestern Region MB-R3-10-29 Service National Forest June 2019 Cover photo: Reflection of mountain peak and forest in Nambe Lake. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Robert H. Moench, US Geological Survey Michael E. Lane, US Bureau

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PAMPHLET TO ACCOMPANY MF-19r,l-A U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE PECOS WILDERNESS, SANTA FE, SAN MIGUEL, NORA, RIO ARRIBA, AND TAGS COUNTIES, NEW MEXICO Robert H. Moench, U.S. Geological Survey Michael E. Lane, U.S. Bureau of Mines STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 2, 1964) and the Joint Conference Report on Senate Bill 4, 88th Congress, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provides that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of the Pecos Wilderness, Santa Fe and Carson National Forests, Santr Fe, San Miguel, Mora, Rio Arriba, and Taos Counties, New Mexico. The nucleus of the Pecos Wilderness was established when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964. Additional adjacent areas were classified as Further Planning and Wilderness during the Second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) by the U.S. Forest Service, January 1979, and some of these were incorporated into the Pecos Wilderness by the New Mexico Wilderness Bill. -

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History

Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past Series: No. 1—SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO No. 2—TAOS—RED RIVER—EAGLE NEST, NEW MEXICO, CIRCLE DRIVE No. 3—ROSWELL—CAPITAN—RUIDOSO AND BOTTOMLESS LAKES STATE PARK, NEW MEXICO No. 4—SOUTHERN ZUNI MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO No. 5—SILVER CITY—SANTA RITA—HURLEY, NEW MEXICO No. 6—TRAIL GUIDE TO THE UPPER PECOS, NEW MEXICO No. 7—HIGH PLAINS NORTHEASTERN NEW MEXICO, RATON- CAPULIN MOUNTAIN—CLAYTON No. 8—MOSlAC OF NEW MEXICO'S SCENERY, ROCKS, AND HISTORY No. 9—ALBUQUERQUE—ITS MOUNTAINS, VALLEYS, WATER, AND VOLCANOES No. 10—SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO No. 11—CUMBRE,S AND TOLTEC SCENIC RAILROAD C O V E R : REDONDO PEAK, FROM JEMEZ CANYON (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by John Whiteside) Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History (Forest Service, U.S.D.A., by Robert W . Talbott) WHITEWATER CANYON NEAR GLENWOOD SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 8 Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, a n d History edited by PAIGE W. CHRISTIANSEN and FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1972 NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES FRANK E. KOTTLOWSKI, Director BOARD OF REGENTS Ex Officio Bruce King, Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo, Superintendent of Public Instruction Appointed William G. Abbott, President, 1961-1979, Hobbs George A. Cowan, 1972-1975, Los Alamos Dave Rice, 1972-1977, Carlsbad Steve Torres, 1967-1979, Socorro James R. -

Tres Arroyos Del Poniente Community Plan

1 Welcome! •This is an open house. •Please sign in and get a name tag. •We invite youview to all walk the aroundposters. and •We are hereregarding to answer the any process, questions the drafts and the anticipated outcomes. •Please feelto free the toposters. add any comments Tres Arroyos Santa Fe County •Please discusscomments any questions with your or neighbors and Community Planning Area County staff. Legend Tres Arroyos Community Planning Area Minor Roads Parcels Major Roads •Grab a drink and some snacks. Roads Intermittent Perennial Rivers and Streams R E I X I S T O A I T P LI Y E A D L E R L L L A N NOP C A A E K M RE LL C K O C MB CA C U TA A B NO E P ONI N I RA T TIER B Department O LA S MIN CA E A N EXI D L Santa Fe County 9 E N RUT A 59 LL S I O T D CA A NM R A T L V PA A R O N O O E O Planning Division S Growth Management PA N C I E M A C ALL T NO CARLOS RAEL C CAMI XI E 9 9 5 M N US NA FERG ON LN MONTOYA PL June 23, 2015 A A N LE CARMILI T CAL A CAMINO I CARLOS RAEL L A E L D M N R I A T L E N ALAMO RD E L O L LL Y A N CA CAMINO MIO C A FAMILY LN ST ST GA C LLEGO S LN A E LN N DA U IX E L N SI B M T O A C R AL NYON VISTA MAEZ RD A W AEZ C O E D M U A LA CIENEGUITA L M B E TERO U O EY S S R Q RLO O CERRO LINDO BL O C E CA tres_arroyos_community_planning_ R CAMIN E ALLE I U ANGE O L L P IN A AMIN C C L A R E CORIAN DER RD C CAMINO TRES ARROYOS area_boundary_6_23_15_poster.mxd W BLUE CANYON WAY O BOYLAN LN L F HARRISON RD E MUSCLE CAR LN TA T A CAMINO DON EMILIO JORGENSEN LN BOYLAN CI JUN L R CALLE A D O DE COMER R LUG AR DE