Potsdamer Platz: the Blurring of the Historic City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DAILY DIARY of PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER DATE ~Mo

THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER DATE ~Mo.. Day, k’r.) U.S. EMBASSY RESIDENCE JULY 15, 1978 BONN, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY THE DAY 6:00 a.m. SATURDAY WOKE From 1 To R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. The President had breakfast with Secretary of State Cyrus R. Vance. 7: 48 The President and the First Lady went to their motorcade. 7:48 8~4 The President and the First Lady motored from the U.S. Embassy residence to the Cologne/Bonn Airport. 828 8s The President and the First Lady flew by Air Force One from the Cologne/Bonn Airport to Rhein-Main Air Base, Frankfurt, Germany. For a list of passengers, see 3PENDIX "A." 8:32 8: 37 The President talked with Representative of the U.S. to the United Nations Andrew J. Young. Air Force One arrived at Rhein-Main Air Base. The President and the First Lady were greeted by: Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) Mrs. Helmut Schmidt Holger Borner, Minister-President, Hesse Mrs. Holger Borner Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Minister of Foreign Affairs, FRG Hans Apel, Minister of Defense, FRG Wolfgang J, Lehmann, Consul General, FRG Mrs. Wolfgang J. Lehmann Gen. William J. Evans, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Air Force, Europe Col. Robert D. Springer, Wing Commander, Rhein-Main Air Base Gen. Gethard Limberg, Chief of the German Air Force 8:45 g:oo The President and Chancellor Schmidt participated in a tour of static display of U.S. -

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

Things to Do in Berlin – a List of Options 19Th of June (Wednesday

Things to do in Berlin – A List of Options Dear all, in preparation for the International Staff Week, we have composed an extensive list of activities or excursions you could participate in during your stay in Berlin. We hope we have managed to include something for the likes of everyone, however if you are not particularly interested in any of the things listed there are tons of other options out there. We recommend having a look at the following websites for further suggestions: https://www.berlin.de/en/ https://www.top10berlin.de/en We hope you will have a wonderful stay in Berlin. Kind regards, ??? 19th of June (Wednesday) / Things you can always do: - Famous sights: Brandenburger Tor, Fernsehturm (Alexanderplatz), Schloss Charlottenburg, Reichstag, Potsdamer Platz, Schloss Sanssouci in Potsdam, East Side Gallery, Holocaust Memorial, Pfaueninsel, Topographie des Terrors - Free Berlin Tours: https://www.neweuropetours.eu/sandemans- tours/berlin/free-tour-of-berlin/ - City Tours via bus: https://city- sightseeing.com/en/3/berlin/45/hop-on-hop-off- berlin?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_s2es 9Pe4AIVgc13Ch1BxwBCEAAYASAAEgInWvD_BwE - City Tours via bike: https://www.fahrradtouren-berlin.com/en/ - Espresso-Concerts: https://www.konzerthaus.de/en/espresso- concerts - Selection of famous Museums (Museumspass Berlin buys admission to the permanent exhibits of about 50 museums for three consecutive days. It costs €24 (concession €12) and is sold at tourist offices and participating museums.): Pergamonmuseum, Neues Museum, -

Germany Berlin Tiergarten Tunnel Verkehrsanlagen Im Zentralen

Germany Berlin Tiergarten Tunnel Verkehrsanlagen im zentralen Bereich – VZB This report was compiled by the German OMEGA Team, Free University Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Please Note: This Project Profile has been prepared as part of the ongoing OMEGA Centre of Excellence work on Mega Urban Transport Projects. The information presented in the Profile is essentially a 'work in progress' and will be updated/amended as necessary as work proceeds. Readers are therefore advised to periodically check for any updates or revisions. The Centre and its collaborators/partners have obtained data from sources believed to be reliable and have made every reasonable effort to ensure its accuracy. However, the Centre and its collaborators/partners cannot assume responsibility for errors and omissions in the data nor in the documentation accompanying them. 2 CONTENTS A PROJECT INTRODUCTION Type of project Project name Description of mode type Technical specification Principal transport nodes Major associated developments Parent projects Country/location Current status B PROJECT BACKGROUND Principal project objectives Key enabling mechanisms Description of key enabling mechanisms Key enabling mechanisms timeline Main organisations involved Planning and environmental regime Outline of planning legislation Environmental statements Overview of public consultation Ecological mitigation Regeneration Ways of appraisal Complaints procedures Land acquisition C PRINCIPAL PROJECT CHARACTERISTICS Detailed description of route Detailed description of main -

Travel with the Metropolitan Museum of Art

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Travel with Met Classics The Met BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB May 9–15, 2022 Berlin with Christopher Noey Lecturer BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Berlin Dear Members and Friends of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Berlin pulses with creativity and imagination, standing at the forefront of Europe’s art world. Since the fall of the Wall, the German capital’s evolution has been remarkable. Industrial spaces now host an abundance of striking private art galleries, and the city’s landscapes have been redefined by cutting-edge architecture and thought-provoking monuments. I invite you to join me in May 2022 for a five-day, behind-the-scenes immersion into the best Berlin has to offer, from its historic museum collections and lavish Prussian palaces to its elegant opera houses and electrifying contemporary art scene. We will begin with an exploration of the city’s Cold War past, and lunch atop the famous Reichstag. On Museum Island, we -

Outlooks, Berlin Panorama

Visiting the Bundestag Information about how you can attend a 23 33 24 26 27 32 plenary sitting or a lecture in the visitors’ 30 37 gallery of the plenary chamber, or take part 31 in a guided tour, can be found on the Bundes 25 44 tag’s website at www.bundestag.de (in the 35 40 “Visit the Bundestag” section). The ‘Visitors’ 34 43 Service will also be pleased to provide de 36 Outlooks tails by telephone on + 49 30 22732152. The 45 roof terrace and the dome are open from 8 a.m. 28 41 Berlin panorama: to midnight daily (last admission at 9.45 p.m.). Berlin Wall Memorial 29 Advance registration is required. You can reg 39 View from the dome ister online at visite.bundestag.de/?lang=en, The MarieElisabeth Lüders Building also by fax (+49 30 22736436 or 30027) or by post houses the publicly accessible Wall Memorial, (Deutscher Bundestag, Besucherdienst, parts of the hinterland wall having been Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin). rebuilt there as a reminder of the division of Germany. Audioguide 42 Bundestag exhibition An audioguide is available for your tour of on German parliamentary history the dome, providing 20 minutes of informa tion about the Reichstag Building and its sur The exhibition on parliamentary history is 38 roundings, the Bundestag, the work of Parl open every day except Mondays from iament and the sights you can see from the 10.00 a.m. to 6.00 p.m., with a later closing dome. The audioguide can be obtained on the time of 7 p.m. -

Throughout the Cold War, USAF Crews Took Advantage of the Air Corridors to Berlin to Spy on the Soviet Forces in East Germany

Throughout the Cold War, USAF crews took advantage of the air corridors to Berlin to spy on the Soviet forces in East Germany. The Berlin For Lunch Bunch By Walter J. Boyne Below: A RB-17G flies a mission over West Germany in the mid- 1950s. Right: Berlin’s famed Brandenburg Gate, just inside the border of East Berlin, is seen in this 1954 surveillance photo taken from a B-17 photo recon aircraft. 56 AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2012 hree air routes to West Berlin well as navigation and landing aids, were The corridors also led to the success- were established after the end of established. Air support to the conference ful covert reconnaissance that was about World War II to give the Western went well, and the Western Allies assumed to begin. Allies air access to their garrisons this would continue as they established The history of the reconnaissance squad- in the former Nazi capital. their garrisons. rons destined to become corridor intel- TWhen the Soviet Union imposed its ligence collectors is intricate. Although blockade in 1948, these air routes be- An Intricate History American recon activity may have begun came famous as the vital corridors of the However, shortly after the conference earlier, the earliest hard evidence notes the Berlin Airlift, which enabled the British ended, the Soviets began to complain that establishment of a special secret Douglas and Americans to supply the beleaguered the Allies were flying outside the agreed A-26 Invader flight within the 45th Re- city. It is less well known that they were corridors and this would not be tolerated. -

8 Days Highlights of Germany

HIGHLIGHTS OF GERMANY | 31 HIGHLIGHTS OF GERMANY BERLIN MUNICH 8 DAYS Germany has been ranked one of the top destinations to visit for 2020. On this 8-day journey including Berlin from and Munich, explore magnificent castles, modern skyscrapers and the stunning Bavarian Alps. Travel in comfort by train admiring the changing landscapes and appreciating the rich history on display throughout $3 ,19 9 your journey. CAD$, PP, DBL. OCC. TOUR OVERVIEW Total 7 nights accommodation; Day 1 Day 6 B 4-Star hotels BERLIN Arrival in Berlin, the capital and largest city in Germany. MUNICH Breakfast at the hotel. Begin your half-day, private Welcome by our local representatives and transfer to your hotel. city tour of Munich, the home of the famous Oktoberfest. Start 4 nights in Berlin 3 nights in Munich Scandic Berlin Potsdamer Platz, Superior Room at the Karlstor, passing the church of St. Michael, the Marienplatz Square with City Hall and its famous Carillon, Private transfers to and from Day 2 B the Frauenkirche and many other attractions of the historic airports and train station center. We recommend a tour of Munich’s old town and the BERLIN After breakfast, begin your private morning city tour of history of beer brewing. Enjoy the rest of your day at leisure First-Class Train Tickets: Berlin, providing an overview of both the historic and perhaps to do some shopping in the area of Alexanderplatz Berlin – Munich contemporary aspects of the city including numerous famous or Friedrichstrasse. Eden Hotel Wolff monuments. See the Kurfürstendamm, the Kaiser-Wilhelm- Private city tours with Gedächtniskirche church, Charlottenburg Castle, the English-speaking Guide Siegessäule, the Government district (Regierungsviertel), the Day 7 B Brandenburg Gate, the Holocaust Memorial, the remains of MUNICH Breakfast at the hotel. -

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017

Designed by Professor Misty Sabol | 7 Days | June 2017 College Study Tour s BERLIN: THE CITY EXPERIENCE INCLUDED ON TOUR Round-trip flights on major carriers; Full-time Tour Director; Air-conditioned motorcoaches and internal transportation; Superior tourist-class hotels with private bathrooms; Breakfast daily; Select meals with a mix of local cuisine. Sightseeing: Berlin Alternative Berlin Guided Walking Tour Entrances: Business Visit KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlinische Galerie (Museum of Modern Art) Topography of Terror Museum 3-Day Museum Pass BMW Motorcycle Plant Tour Reichstag Jewish Holocaust Memorial Overnight Stays: Berlin (5) NOT INCLUDED ON TOUR Optional excursions; Insurance coverage; Beverages and lunches (unless otherwise noted); Transportation to free-time activities; Customary gratuities (for your Tour Director, bus driver and local guide); Porterage; Adult supplement (if applicable); Weekend supplement; Shore excursion on cruises; Any applicable baggage-handing fee imposed by the airlines SIGN UP TODAY (see efcollegestudytours.com/baggage for details); Expenses caused by airline rescheduling, cancellations or delays caused by the airlines, bad efcst.com/1868186WR weather or events beyond EF’s control; Passports, visa and reciprocity fees YOUR ITINERARY Day 1: Board Your Overnight Flight to Berlin! Day 4: Berlin Day 2: Berlin Visit a Local Business Berlin's outstanding infrastructure and highly qualified and educated Arrive in Berlin workforce make it a competitive location for business. Today you will Arrive in historic Berlin, once again the German capital. For many visit a local business. (Please note this visit is pending confirmation years the city was defined by the wall that separated its residents. In and will be confirmed closer to departure.) the last decade, since the monumental events that ended Communist rule in the East, Berlin has once again emerged as a treasure of arts Receive a 3 Day Museum Pass and architecture with a vibrant heart. -

TOP10 Sehenswürdigkeiten in Berlin Sightseeing-Tour Mit Dem Berliner Nahverkehr

TOP10 Sehenswürdigkeiten in Berlin Sightseeing-Tour mit dem Berliner Nahverkehr Wegbeschreibung für Bus & Bahn Reine Fahrtzeit: 54 Minuten Anzahl genutzte Haltestellen: 30 1 East Side Gallery und Oberbaumbrücke Lage: Warschauer Straße, Ecke Mühlenstraße Station: S + U Bhf. Warschauer Straße Bahnen: S5, S7, S75, U1 Die Oberbaumbrücke bildet den Übergang von Warschauer Str. zu Skalitzer Str. Die East Side Gallery beginnt Warschauer Str. / Ecke Mühlenstr. Wegbeschreibung zum Alexanderplatz: - S-Bahn S5, S7, S75 Richtung Spandau / Potsdam / Olympiastadion - 3 Stationen bis Zielbahnhof Alexanderplatz fahren © 2017 leinwandfoto.de 1 4 Fernsehturm und Weltzeituhr Lage: Alexanderplatz, Panoramastraße Station: S+U Alexanderplatz Bahnen: S5, S7, S75, U2, U5, U8 Busse: TXL, 100, 200, M48 Der Fernsehturm befindet sich in Fahrtrichtung links. Die Weltzeituhr steht direkt auf dem Alexanderplatz auf der anderen Seite des Bahnhofs. Wegbeschreibung zum Berliner Dom: - Bus 100 oder 200 Richtung Zoologischer Garten - 2 Stationen bis Zielbahnhof Lustgarten fahren 23 Berliner Dom und Berliner Stadtschloss Lage: Am Lustgarten Station: Lustgarten Busse: TXL, 100, 200 Der Berliner Dom ist in Fahrtrichtung rechts gelegen, das Stadtschloss linker Hand. Wegbeschreibung zur Museumsinsel: - Zu Fuß am Berliner Dom vorbei und Straße Am Lustgarten folgen - In die Bodestraße einbiegen 7 Museumsinsel Lage: Am Lustgarten Station: Lustgarten Busse: TXL, 100, 200 Die Museumsinsel mit Neuem Museum, Pergamonmuseum, Alte Nationalgalerie etc. befindet sich vor dem Betrachter! -

Marking the 20Th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall Responsible Leadership in a Globalized World

A publication of the Contributors include: President Barack Obama | James L. Jones Chuck Hagel | Horst Teltschik | Condoleezza Rice | Zbigniew Brzezinski [ Helmut Kohl | Colin Powell | Frederick Forsyth | Brent Scowcroft ] Freedom’s Challenge Marking the 20th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall Responsible Leadership in a Globalized World The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, not only years, there have been differences in opinion on important led to the unifi cation of Germany, thus ending decades of issues, but the shared interests continue to predominate. division and immeasurable human suffering; it also ended It is important that, in the future, we do not forget what binds the division of Europe and changed the world. us together and that we defi ne our common interests and responsibilities. The deepening of personal relations between Today, twenty years after this event, we are in a position to young Germans and Americans in particular should be dear gauge which distance we have covered since. We are able to to our hearts. observe that in spite of continuing problems and justifi ed as well as unjustifi ed complaints, the unifi cation of Germany and For this reason the BMW Foundation accounts the Europe has been crowned with success. transatlantic relationship as a focus of its activity. The Transatlantic Forum for example is the “veteran“ of the It is being emphasized again and again, and rightly so, that it BMW Foundation’s Young Leaders Forums. The aim of was the people in the former GDR that started the peaceful these Young Leaders Forums is to establish a network, revolution. -

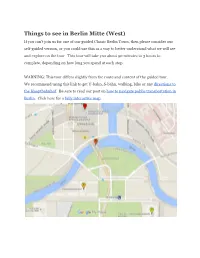

Things to See in Berlin Mitte (West)

Things to see in Berlin Mitte (West) If you can't join us for one of our guided Classic Berlin Tours, then please consider our self-guided version, or you could use this as a way to better understand what we will see and explore on the tour. This tour will take you about 90 minutes to 3 hours to complete, depending on how long you spend at each stop. WARNING: This tour differs slightly from the route and content of the guided tour. We recommend using this link to get U-bahn, S-bahn, walking, bike or any directions to the Hauptbahnhof. Be sure to read our post on how to navigate public transportation in Berlin. Click here for a fully interactive map. A - Berlin Central Station The huge glass building from 2006 is Europe’s biggest railroad junction – the elevated rails are for the East-West-connection and underground is North-South. Inside it looks more like a shopping mall with food court and this comes in handy, as Germany’s rather strict rules about Sunday business hours do not apply to shops at railroad stations. B - River Spree Cross Washington Platz outside the station and Rahel-Hirsch-Straße, turn right and use the red bridge with the many sculptures, to cross the River Spree. Berlin has five rivers and several canals. In the city center of Berlin, the Spree is 44 km (27 ml) and its banks are very popular for recreation. Look at the beer garden “Capital Beach” on your left! C - German Chancellery (Bundeskanzleramt) Crossing the bridge, you already see the German Chancellery (Bundeskanzleramt) from 2001, where the German chancellor works.