Emergency Department Procedural Sedation with Propofol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement on Safe Use of Propofol 2019

Statement on Safe Use of Propofol Committee of Origin: Ambulatory Surgical Care (Approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 27, 2004, and amended on October 23, 2019) Because sedation is a continuum, it is not always possible to predict how an individual patient will respond. Due to the potential for rapid, profound changes in sedative/anesthetic depth and the lack of antagonist medications, agents such as propofol require special attention. Even if moderate sedation is intended, patients receiving propofol should receive care consistent with that required for deep sedation. The Society believes that the involvement of an anesthesiologist in the care of every patient undergoing anesthesia is optimal. However, when this is not possible, non-anesthesia personnel who administer propofol should be qualified to rescue* patients whose level of sedation becomes deeper than initially intended and who enter, if briefly, a state of general anesthesia.** • The physician responsible for the use of sedation/anesthesia should have the education and training to manage the potential medical complications of sedation/anesthesia. The physician should be proficient in airway management, have advanced life support skills appropriate for the patient population, and understand the pharmacology of the drugs used. The physician should be physically present throughout the sedation and remain immediately available until the patient is medically discharged from the post procedure recovery area. • The practitioner administering propofol for sedation/anesthesia should, at a minimum, have the education and training to identify and manage the airway and cardiovascular changes which occur in a patient who enters a state of general anesthesia, as well as the ability to assist in the management of complications. -

Intravenous Sedation and Preparing for Your Procedure

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Intravenous sedation and preparing for your procedure Information for patients Please ensure that you read this leaflet before you come to hospital for your operation What is sedation? Sedation is a way of using drugs (sedatives) to make you feel relaxed and sleepy during your procedure. We will give you your sedatives through an injection into a vein. Sedation is not a general anaesthetic and you will not be unconscious. You may not remember much of what happens during the procedure and directly afterwards. This is quite normal. Local anaesthetic will be given once you have been sedated. Do not drive, operate machinery or sign important documents for at least 24 hours after your procedure. You must make sure that you have a responsible adult with you who can stay in the department for a couple of hours and take you home by car or taxi. Someone must also stay with you for at least 24 hours after your procedure. Your procedure will be cancelled if you do not bring someone with you who can do this. Preparation for your procedure and what to bring with you • Patients having a procedure under sedation must follow the current fasting guidelines for general anaesthesia. You must not eat or drink for 6 hours before your procedure but you may have water up to 2 hours before. If you do eat or drink after these times your surgery will be cancelled. • Avoid alcohol for 24 hours before your procedure. • Bring with you a list of any medication or drugs you are taking. -

Moderate Sedation Study Guide 11-17-10

PROCEDURE RELATED SEDATION Outline I Introduction II Definitions: The 5 Levels of Sedation and Anesthesia III Emergency Procedures, Critical Care Areas and Policy Exclusions IV The Pre-Sedation Assessment V NPO: The Timing of Eating and Drinking before Sedation VI Review of Some Agents Used for Sedation VII Orders for Procedure Related Sedation VIII Environmental Requirements and Monitoring During Sedation IX Post-Procedure Monitoring and the PAR Score X Discharge Criteria and Concluding Post-Procedure Monitoring 1 PROCEDURE RELATED SEDATION Lance Brown, MD, MPH I. Introduction The purpose of this tutorial is to familiarize the reader with the Loma Linda University Medical Center Policy M-86 for Procedure Related Sedation. Procedure related sedation is used to make necessary medical procedures as comfortable as possible for patients and to facilitate the performance of necessary medical procedures by health care providers (typically physicians). It is important for health care providers performing procedure related sedation to be familiar with the pharmacologic characteristics of the agents being used, to understand the risk factors for complications related to procedure related sedation, and to individually plan the sedation for each patient. Each health care practitioner privileged to provide procedure related sedation takes responsibility for both the comfort and safety of the patients in their care. II. Definitions At Loma Linda University Medical Center, we have defined five distinct levels of sedation and anesthesia. Familiarity with the definitions of these levels of sedation is important for safely providing procedure related sedation and for complying with the policy of the Medical Center. It must be recognized, however, that sedation occurs along a continuum and that individual patients may have different degrees of sedation for a given dose and route of medication. -

Post-Intubation Analgesia and Sedation

POST-INTUBATION ANALGESIA AND SEDATION August 2012 J Pelletier Intubated patients experience pain and anxiety Mechanical ventilation, endotracheal tube Blood draws, positioning, suctioning Surgical procedures, dressing changes Awareness during neuromuscular blockade Invasive catheters Loss of control Unrelieved pain and anxiety cause adverse effects Self-injury and removal of life-sustaining devices Increased endogenous catecholamines Sleep deprivation, anxiety, and delirium Impaired post-ICU psychological recovery Emotional and posttraumatic effects Ventilator dysynchrony Immunosuppression Treating pain and anxiety improves outcomes Use of pain and sedation scales in critically ill patients allows: precise dosing reduced medication side effects reduced ICU and hospital length of stay shorter duration of mechanical ventilation Analgesics should be provided first, then anxiolysis If you were intubated, how much lorazepam or midazolam, and fentanyl would you want per hour? Intubated ED patients receive inadequate analgesia and sedation Retrospective study, tertiary ED 50% received no analgesia, 30% received no anxiolytic Of patients receiving postintubation vecuronium, 96% received either no or inadequate anxiolysis or analgesia Overall, 3 of 4 patients received no or inadequate analgesia and an equivalent number received no or inadequate anxiolysis Bonomo 2007 Analgesia: opioids Bind CNS and peripheral tissue receptors Mu-1 receptors: analgesia Mu-2 receptors: respiratory depression, vomiting, constipation, and -

The Waterloo Wellington Palliative Sedation Protocol

The Waterloo Wellington Palliative Sedation Protocol Waterloo Wellington Interdisciplinary HPC Education Committee; PST Task Force Chair: Dr. Deborah Robinson MD CCFP(F), Focused practice in Oncology and Palliative Care Co-chairs: Cathy Joy, Palliative Care Consultant, Waterloo Region Chris Bigelow, Palliative Care Consultant, Wellington County Revision due: November 2016 Last revised and activated: November 13, 2013 Committee responsible for revisions: WW Interdisciplinary HPC Education Committee Table of Contents Purpose and Definitions .................................................................................................................... 2 Indications for the use of PST .............................................................................................................. 3 Criteria for Initiation of PST ............................................................................................................... 4 Process ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Documentation for Initiation of PST .................................................................................................. 5 Medications ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1st Line (Initiating PST) ...................................................................................................................... 6 2nd Line (When 1st -

Tracheal Intubation Intubação Traqueal

0021-7557/07/83-02-Suppl/S83 Jornal de Pediatria Copyright © 2007 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria ARTIGO DE REVISÃO Tracheal intubation Intubação traqueal Toshio Matsumoto1, Werther Brunow de Carvalho2 Resumo Abstract Objetivo: Revisar os conceitos atuais relacionados ao procedimento Objective: To review current concepts related to the procedure of de intubação traqueal na criança. tracheal intubation in children. Fontes dos dados: Seleção dos principais artigos nas bases de Sources: Relevant articles published from 1968 to 2006 were dados MEDLINE, LILACS e SciELO, utilizando as palavras-chave selected from the MEDLINE, LILACS and SciELO databases, using the intubation, tracheal intubation, child, rapid sequence intubation, keywords intubation, tracheal intubation, child, rapid sequence pediatric airway, durante o período de 1968 a 2006. intubation and pediatric airway. Síntese dos dados: O manuseio da via aérea na criança está Summary of the findings: Airway management in children is relacionado à sua fisiologia e anatomia, além de fatores específicos related to their physiology and anatomy, in addition to specific factors (condições patológicas inerentes, como malformações e condições (inherent pathological conditions, such as malformations or acquired adquiridas) que influenciam decisivamente no seu sucesso. As principais conditions) which have a decisive influence on success. Principal indicações são manter permeável a aérea e controlar a ventilação. A indications are in order to maintain the airway patent and to control laringoscopia e intubação traqueal determinam alterações ventilation. Laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation cause cardiovascular cardiovasculares e reatividade de vias aéreas. O uso de tubos com alterations and affect airway reactivity. The use of tubes with cuffs is not balonete não é proibitivo, desde que respeitado o tamanho adequado prohibited, as long as the correct size for the child is chosen. -

Comparison of Propofol Alone and in Combination with Ketamine Or

Clinical Research Article pISSN 2005-6419 • eISSN 2005-7563 KJA Comparison of propofol alone and Korean Journal of Anesthesiology in combination with ketamine or fentanyl for sedation in endoscopic ultrasonography Shweta A Singh1, Kelika Prakash1, Sandeep Sharma1, Gaurav Dhakate1, and Vikram Bhatia2 Departments of 1Anaesthesiology and Critical Care and 2Hepatology, Institute of Liver & Biliary Sciences, New Delhi, India Background: We evaluated whether the addition of a small dose of ketamine or fentanyl would lead to a reduction in the total dose of propofol consumed without compromising the safety and recovery of patients having endoscopic ultraso- nography (EUS). Methods: A total of 210 adult patients undergoing elective EUS under sedation were included in the study. Patients were randomized into three groups. Patients were premedicated intravenously with normal saline in group 1, 50 µg fentanyl in group 2, and 0.5 mg/kg ketamine in group 3. All patients received intravenous propofol for sedation. Propofol consump- tion in mg/kg/h was noted. The incidence of hypotension, bradycardia, desaturation, and coughing was noted. The time to achieve a Post Anesthesia Discharge Score (PADS) of 10 was also noted. Results: There were 68 patients in group 1, 70 in group 2, and 72 in group 3. The amount of propofol consumed was significantly higher in group 1 (9.25 [7.3–13.2]) than in group 2 (8.8 [6.8–12.2]) and group 3 (7.6 [5.7–9.8]). Patient he- modynamics and oxygenation were well maintained and comparable in all groups. The time to achieve a PADS of 10 was significantly higher in group 3 compared to the other two groups. -

Inhaled Methoxyflurane (Penthrox) Sedation for Third Molar Extraction

Australian Dental Journal The official journal of the Australian Dental Association Australian Dental Journal 2011; 56: 296–301 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01350.x Inhaled methoxyflurane (Penthroxâ) sedation for third molar extraction: a comparison to nitrous oxide sedation WA Abdullah,* SA Sheta,* NS Nooh* *Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Dakahlia, Egypt. ABSTRACT Background: The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of inhaled methoxyflurane (PenthroxÒ) in the reduction of dental anxiety in patients undergoing mandibular third molar removal in a specialist surgical suite and compare it to the conventional nitrous oxide sedation. Methods: A prospective randomized, non-blinded crossover design study of 20 patients receiving two types of sedation for their third molar extraction who participated in 40 treatment sessions. At first appointment, a patient was randomly assigned to receive either nitrous oxide sedation or intermittent PenthroxÒ inhaler sedation, with the alternate regimen administered during the second appointment. Peri-procedural vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure) were recorded and any deviations from 20% from the baseline values, as well as any drop in oxygen saturation below 92% were documented. The Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS) score was recorded every five minutes. Patient cooperation during the procedure, patients’ general opinion about the sedation technique, surgeon satisfaction and the occurrence of side effects were all recorded. After the second procedure, the patient was also asked if he or she had any preference of one sedation technique over the other. -

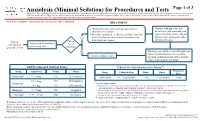

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests Page 1 of 3 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. Note: Refer to UTMDACC Institutional Policy #CLN0502 for complete information. TREATMENT ● Document mental status and vital signs prior to Continue with procedure and administering sedation document mental status and vital ● Determine appropriate medication and dose based on signs after administering sedation onset of action (see chart below) of anxiolytic for and prior to beginning procedure Yes 1 desired patient response and post-procedure Patient Patient Assess need for anxiolysis scheduled for needs prior to procedure procedure or test anxiolysis? No Discharge patient when clinically stable and follow institutional processes regarding Continue with procedure discharge instructions and criteria for both inpatient and outpatient settings 2,3 Adult Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing Pediatric Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing3,5,6 Maximum Drug Adult Dose Route Onset Drug Pediatric Dose Route Onset Dose 4 Midazolam 5 – 10 mg PO 10-30 minutes Midazolam 0.5 – 1 mg/kg/dose PO 10-20 minutes 5 mg 0.5 – 2 mg PO 30-60 minutes Lorazepam 5 Pediatric considerations: 1 – 4 mg IM 20-30 minutes ● Consider lower dosing strategies for patients with cardiac or respiratory compromise, and those who received concomitant opiates, benzodiazepines or similar synergistic sedative medications. -

Conscious Sedation of Children with Propofol Is Anything but Conscious

Conscious Sedation of Children With Propofol Is Anything but Conscious Scott T. Reeves, MD; Jeana E. Havidich, MD; and D. Patrick Tobin, CRNA ABSTRACT. Objective. To determine the depth of se- taining adequate cardiopulmonary function and the dation required for bone marrow aspiration and intrathe- ability to respond purposefully to verbal command cal injection of chemotherapeutic agents in children us- and/or to tactile stimulation.”1 Recently, the Joint ing a bispectral (BIS) index monitor and clinical Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organi- assessment by an independent observer. zations (JCAHO) revised its standards for anesthesia Methods. Sixteen children who were undergoing 19 2 intrathecal chemotherapy and bone marrow aspirations and sedation. This revision was required by changes were enrolled in the study. Their ages ranged from 23 in anesthesia and sedation practices, which have months to 190 months with a mean of 79 months. The BIS moved from the operating room setting to peripheral index was recorded every 5 minutes by an independent sites such as ambulatory care clinics. In addition, observer. The patients received only intravenous propo- potent intravenous induction anesthetics, including fol for sedation. There were no complications during the propofol, have entered the mainstream of sedation procedures. practice. Results. The mean BIS score was 62.8 ؎ 9.6. The mean -low BIS score was 29.7 ؎ 13.7, indicating a level of deep The objective of this prospective study was to de sedation and/or general anesthesia was necessary to in- termine the level of sedation (conscious vs deep), duce the desired stated of consciousness that would per- using a bispectral (BIS) index monitor, provided by mit the practitioner to perform the procedure. -

Elective Intubation

Elective Intubation Charles G Durbin Jr MD FAARC, Christopher T Bell MD, and Ashley M Shilling MD Introduction Intubation: Perioperative Versus Outside the Operating Room Patient Examination and Airway Evaluation Predictors of a Difficult Airway Mouth Opening and Dentition Oral Cavity and Neck Mobility Evaluation Physiologic Risks of Intubation Environmental Assessment and Preparation Managing Airway Risks Outside the Operating Room Monitoring Intubation: Plans A, B, and C Preparing for Intubation Physical Considerations and Time-Out Denitrogenation or Preoxygenation Intubation Using Direct Laryngoscopy Initial Plan Confirmation of Tracheal Intubation Physiologic Changes and Management Strategies Alternative Airway Plans Postintubation Plans Transfer of Care After the Difficult Intubation: A Case Review Conclusions Endotracheal intubation is a commonly performed operating room (OR) procedure that provides safe delivery of anesthetic gases and airway protection during surgery. The most common intuba- tion technique in the perioperative environment is direct laryngoscopy with orotracheal tube in- sertion. Infrequently, difficulties that require an alternative intubation technique are encountered due to patient anatomy, equipment limitations, or patient pathophysiology. Careful patient evalu- ation, advanced planning, equipment preparation, system redundancy, use of checklists, familiarity with airway algorithms, and availability of additional help when needed during OR intubations have resulted in exceptional success and safety. Airway difficulties during intubation outside the controlled environment of the OR are more frequent and more serious. Translating the intubation processes practiced in the OR to intubations outside the perioperative setting should improve patient safety. This paper considers each step in the OR intubation process in detail and proposes ways of incorporating perioperative procedures into intubations outside the OR. -

A Guide to Fast, Effective Pain Management Designed for Fast, Efficient Patient Management

NEW Advancing Acute Pain Management At last, PENTHROX® is here... A guide to Fast, effective pain management designed for fast, efficient patient management. Inhaled patient-controlled analgesia PENTHROX is indicated for the emergency relief of moderate to severe pain in conscious adult patients with trauma and associated pain What is inhaled patient-controlled analgesia? Inhaled patient-controlled analgesia allows fully conscious patients to self-administer analgesia by inhaling a gas through a facemask or mouthpiece. The patient determines the concentration of drug delivered. Although various inhalational anaesthetics have been used for inhaled patient-controlled analgesia (examples include isoflurane and sevoflurane) there are currently only two drugs licensed for this purpose in the UK: nitrous oxide 50% combined with oxygen 50% (N2O/O2) and methoxyflurane. Inhaled patient-controlled analgesia has the advantage over oral and parenteral drugs in that it is non-narcotic, with minimal side effects. It allows the patient to regulate the dose he/she receives while requiring relatively little training for the clinician. Table 1 outlines some indications for inhaled analgesia. Penthrox is indicated for the emergency relief of moderate to severe pain in conscious adult patients with Adverse events should be reported. On the other hand, inhaled patient-controlled trauma and associated pain. Please consult the Summary Reporting forms and information can be analgesia has to be used with the same caution of Product Characteristics before prescribing. Information found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard. Dr John Wright is Consultant in Emergency about this product, including adverse reactions, Adverse events should also be reported to as other forms of analgesia in some cases, such Galen Limited on 028 3833 4974 and select Medicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle- precautions, contra-indications and method of use can as patients with head injury, while it is uniquely be found at www.medicines.org.uk/emc.