The Silent Side of Sponsorship: an Explorative Study of Relational Determinants for Shared Value Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Godkendt Årsrapport for FC Midtjylland 2017/2018

FC Midtjylland A/S Kaj Zartows Vej 5, DK-7400 Herning Årsrapport for 1. juli 2017 - 30. juni 2018 Annual Report for 1 July 2017 - 30 June 2018 CVR-nr. 31 57 61 56 Årsrapporten er fremlagt og godkendt på selskabets ordi- nære generalforsamling den 29/10 2018 The Annual Report was presented and adopted at the Annual General Meeting of the Company on 29/10 2018 Penneo document key: K2L7L-5G3PS-8A3SQ-DBTDV-S2ZEG-E7P0M Albert Kusk Dirigent Chairman of the General Meeting Indholdsfortegnelse Contents Side Page Påtegninger Management’s Statement and Auditor’s Report Ledelsespåtegning 1 Management’s Statement Den uafhængige revisors revisionspåtegning 2 Independent Auditor’s Report Ledelsesberetning Management’s Review Selskabsoplysninger 7 Company Information Hoved- og nøgletal 8 Financial Highlights Ledelsesberetning 10 Management’s Review Årsregnskab Financial Statements Resultatopgørelse 1. juli - 30. juni 25 Income Statement 1 July - 30 June Balance 30. juni 26 Balance Sheet 30 June Egenkapitalopgørelse 30 Statement of Changes in Equity Pengestrømsopgørelse 1. juli - 30. juni 31 Cash Flow Statement 1 July - 30 June Noter til årsregnskabet 33 Penneo document key: K2L7L-5G3PS-8A3SQ-DBTDV-S2ZEG-E7P0M Notes to the Financial Statements Translation of the Danish original. In case of discrepancy, the Danish version shall prevail. Ledelsespåtegning Management’s Statement Bestyrelse og direktion har dags dato behandlet og The Executive Board and Board of Directors have godkendt årsrapporten for regnskabsåret 1. juli 2017 today considered and adopted the Annual Report of - 30. juni 2018 for FC Midtjylland A/S. FC Midtjylland A/S for the financial year 1 July 2017 - 30 June 2018. -

Fra Amatørisme Til Professionalisme

Fra amatørisme til professionalisme Rasmus Troels Krarup Hjortshøj Speciale Historie, Aalborg Universitet September 2007 Titelblad 1. Dansk titel: Fra amatørisme til professionalisme 2. English title: From amateurism to professionalism 3. Vejleder: Knud Knudsen 2 Forord Jeg vil gerne rette en tak til vejleder Knud Knudsen for god og konstruktivt vejledning. Endvidere skal der lyde tak til Tommy Poulsen og Lynge Jacobsen for at afse tid til interviews. Tak skal der ligeledes lyde til personalet ved sportsarkivet i Horsens og på Horsens Bibliotek, hvor jeg begge steder er blevet mødt med stor hjælpsomhed og interesse. ___________________________ Rasmus Troels Krarup Hjortshøj 3 Indholdsfortegnelse 1. Indledning ................................................................................................................................. 7 2. Problemformulering.................................................................................................................. 8 2.1. Temabeskrivelse ................................................................................................................. 8 3. Specialets opbygning .............................................................................................................. 9 3.1. Metode............................................................................................................................ 9 3.2. Analyseramme................................................................................................................ 9 3.3. Fra amatørisme til professionalisme -

Års Beretning 2011

ÅRSBERETNING 2011 ÅRS BERETNING 2011 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Mikkel Minor Petersen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Carl Herup Høgnesen Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk m.fl. Redaktion slut 16. februar 2012 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 31,00 i forsendelse 320752_Omslag_2011.indd 1 14/02/12 15.10 ÅRSBERETNING 2011 ÅRS BERETNING 2011 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Mikkel Minor Petersen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Carl Herup Høgnesen Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk m.fl. Redaktion slut 16. februar 2012 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 31,00 i forsendelse 320752_Omslag_2011.indd 1 14/02/12 15.10 Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2011 Indhold Dansk Boldspil-Union U20-landsholdet . 56 Dansk Boldspil-Union 2011 . 4 U19-landsholdet . 57 UEFA U21 EM 2011 Danmark . 8 U18-landsholdet . 58 Nationale relationer . 10 U17-landsholdet . 60 Internationale relationer . 12 U16-landsholdet . 62 Medlemstal . 14 Old Boys-landsholdet . 63 Organisationsplan 2011 . 16 Kvindelandsholdet . 64 Administrationen . 18 U23-kvindelandsholdet . 66 Bestyrelsen og forretningsudvalget . 19 U19-kvindelandsholdet . 67 Udvalg . 20 U17-pigelandsholdet . 68 Repræsentantskabet . 22 U16-pigelandsholdet . -

Årsskrift 2009 200 9 Vejle Boldklub

Årsskrift 2009 VEJLE BOLDKLUB 2009 Vejle BoldkluB ÅRSSkRIFT 2009 56. årgang På gensyn i: Spar Nord Vejle Havneparken 4, tlf. 76 41 41 00 www.sparnord.dk/vejle Den direkte vej mod målet... - en sikker Topscorer! Vestergade 28 B · 7100 Vejle Tlf. 75 72 04 44 · Fax 75 72 16 18 Vejlevej 29 · 7300 Jelling · Tlf 75 87 18 43 www.petrowsky.dk 2 Vejle BoldkluB ÅRSSkRIFT 2009 56. årgang 3 LEVERANDØR TIL VEJLE BOLDKLUB VB Shoppen er fyldt med originale spillebluser · originale shorts/strømper halstørklæder · caps · penalhuse · støvleposer · nøglebånd · drikkedunke huer · svedbånd · VB armbånd - hele tiden nyheder! Vi har klædt VB på i mange år sammen med hummel - fra miniputter over damer til veteraner og divisionsholdet. HC SPORT - VEJLE Torvegade 9 - 7100 Vejle - Tlf. 75 82 15 99 4 Forord VB’s Årsskrift udkom første gang i 1954 Vi håber, at alle medlemmer, forældre, med følgende indledning: sponsorer og alle øvrige interessenter i og omkring klubben vil få glæde af dette flotte En tradition skabes… årsskrift endnu engang. ”de seneste år i Vejle Boldklubs historie har stået i den sportslige fremgangs tegn, Året 2009 blev også et år med væsentlige således som alle i VB og VB`s Venner helst begivenheder i VB`s historie: ser udviklingen forme sig for deres gamle - Sidste kamp på Nordre Stadion blev spillet klub. Men denne side af klubbens udvikling 25. juni. er ikke tilstrækkelig. den skal følges med - VB Parkens etablering blev endelig sat initiativ og fremskridt inden for ledelsen, i gang 29. juni med første spadestik til det være sig bestyrelsen eller udvalgene. -

Værdiansættelse Af Brøndby If

INFORMATION Dato: 06‐05‐2020 Anslag ekskl. forside, referencer, bilag figur & tabelliste: 123.078. Antal normalsider: 54. Vejleder: Jesper Storm. Simon Ersgaard Studie nr.: S108781 Afgangsprojekt HD(R) VÆRDIANSÆTTELSE AF BRØNDBY IF Strategisk‐ og regnskabsanalyse af Brøndby IF Simon Ersgaard HD(R) 06‐05‐2020 Afgangsprojekt Indholdsfortegnelse 1. Indledning ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Problemfelt ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Problemformulering ........................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Afgrænsning ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Metode og fremgangsmåde .................................................................................................... 7 1.4.1 Projektet ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.2 Empiri/Metodevalg – Teori og modeller ........................................................................... 7 1.4.3 Fremgangsmåden ............................................................................................................. 9 1.4.3 Kilder ................................................................................................................................ -

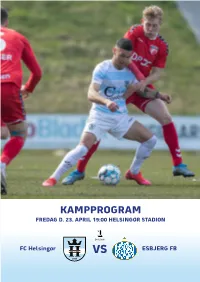

Kampprogram Fredag D

KAMPPROGRAM FREDAG D. 23. APRIL 19:00 HELSINGØR STADION FC Helsingør VS ESBJERG FB Erhvervs Partner LOKAL TOLK Murermester Egon Geertsen Helsingør Golf Club Krone Partner Tribune Partner Hovedsponsor Guld Partner Sølv Partner 3000 Partner Ajour Nordsjællands Brandskole Fredensborg Vinimport ApS Næsby - Den Søde Bager Helsingør Ventilation Oasen Kebab Mama Rosa Popcornmanden.dk Rib house Ralphs Cykler Baktotal Restaurant Strandborg Trolle Company Rico Mens Wear 12’er Pubben Riva Pizza & Steak House 360 Business Tool MP Enterprise Blomsterhjørnet Nordsjællands Proviant Landinspektørkontoret Kamppartner Kampboldpartner TRÆNERE Morten Eskesen Mikkel Thygesen ANGREB 77 10 8 Lucas Haren Jeppe Kjær Callum McCowatt 98 12 Liam Jordan Sebastian Czajkowski MIDTBANE 30 2 42 Tonni Adamsen Nicklas Mihkel Ainsalu Mouritsen 21 11 88 Carl Lange David Boysen Daniel Norouzi 7 27 17 Anders Holst Elijah Just Oliver Kjærgaard 23 19 28 Frederik Matias Philip Rejnhold Christensen Christensen FORSVAR 33 6 3 Hans Bonnesen Nikolaj Hansen Frederik Bay 20 25 Jonas Henriksen Dalton Wilkins 14 5 Nicolai Geertsen Brandon Onkony MÅLMÆND 31 97 1 Frederik Christoffer Kevin Stuhr Rosenqvist Petersen Ellegaard Tøj Partner Vi har virkelig glædet Begge vores to tidligere kampe mod Esbjerg har været underholdende. I os til at være sammen Esbjerg var der både flotte mål, et med jer tilskuere straffespark, en udvisning og generelt flot spil fra begge hold. På Tilskuere på stadion er den bedste hjemmebane var det et tæt opgør hvor nyhed vi har fået i 2021. Vi har virkelig Esbjerg var lidt skarpere på dagen set frem til denne dag hvor vi i end vi var. Esbjerg har kæmpet om fællesskab kan opleve en oprykning til superligaen fra runde 1 fodboldkamp sammen. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2014/15 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadio Olimpico - Turin Thursday 2 October 2014 21.05CET (21.05 local time) Torino FC Group B - Matchday 2 FC København Last updated 30/09/2014 12:21CET Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Team facts 4 Squad list 6 Fixtures and results 8 Match-by-match lineups 11 Match officials 13 Legend 14 1 Torino FC - FC København Thursday 2 October 2014 - 21.05CET (21.05 local time) Match press kit Stadio Olimpico, Turin Previous meetings Head to Head No UEFA competition matches have been played between these two teams Torino FC - Record versus clubs from opponents' country Torino FC have not played against a club from their opponents' country FC København - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Vidal 29 (P), 61 (P), 27/11/2013 GS Juventus - FC København 3-1 Turin 63; Mellberg 56 N. Jørgensen 14; 17/09/2013 GS FC København - Juventus 1-1 Copenhagen Quagliarella 54 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Crespo 48, 63, 4-1 21/08/2001 QR3 SS Lazio - FC København Rome Claudio López 64, agg: 5-3 Fiore 90; Zuma 81 Laursen 73 (P), 08/08/2001 QR3 FC København - SS Lazio 2-1 Copenhagen Fernandez 85; Crespo 56 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 1-0 03/11/1993 R2 AC Milan - FC København Milan Papin 44 agg: 7-0 Papin 1, 72, Simone 20/10/1993 R2 FC København - AC Milan 0-6 Copenhagen 5, 15, B. -

Annual Review 2020 Central Business Registration No

Orifarm Group A/S Energivej 15 5260 Odense S Denmark ÆR NEM KET VA Phone +45 63 95 27 00 S Annual Review 2020 Central Business Registration no. 27347282 www.orifarm.com Tryksag 5041 0826 Scandinavian Print Group CONTENTS Letter from the CEO 03 An incredible year The business 04 Orifarm in brief 06 Our business 12 2020 highlights The foundation 14 25th anniversary 15 Ambitious ownership 16 Who we are 18 New ways of working 20 Supporting talents outside Orifarm 21 Donations and charity 22 Integrating sustainability 24 A game-changing acquisition 28 Room for growth Executive Management 30 Orifarm’s Executive Management 32 More bright years ahead of us Company details and key figures 33 Company details 34 Key figures Annual Review 2020 1 Letter from the CEO An incredible year 2020 is a year we will never forget. Whether we • In August, Hans Bøgh-Sørensen took over as focus on the COVID-19 pandemic and its conse- Chairman of the Board of Directors quences worldwide, on Orifarm and our business primarily in Europe, or on each and every one of • In April, Orifarm signed and announced the big- us as individuals, we learned during the year that gest acquisition in the history of the company. things we took for granted when entering 2020 An acquisition from Takeda including more than were suddenly changed or simply not possible 100 products, two production facilities and more anymore. than 600 employees. This acquisition is a major milestone and will be a true game changer for 2020 will always be linked to the COVID-19 virus, Orifarm going forward and it is impossible to do a 2020 review without touching upon the pandemic and its many unfor- We also expect 2021 to be a bright year for Ori- tunate consequences. -

First Division Clubs in Europe 2016/17

Address List - Liste d’adresses - Adressverzeichnis 2016/17 First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs de première division en Europe Klubs der ersten Divisionen in Europa WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES | INHALTSVERZEICHNIS UEFA CLUB COMPETITIONS CALENDAR – 2016/17 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 3 CALENDAR – 2016/17 UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 4 UEFA MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS Albania | Albanie | Albanien 5 Andorra | Andorre | Andorra 7 Armenia | Arménie | Armenien 9 Austria | Autriche | Österreich 11 Azerbaijan | Azerbaïdjan | Aserbaidschan 13 Belarus | Belarus | Belarus 15 Belgium | Belgique | Belgien 17 Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bosnie-Herzégovine | Bosnien-Herzegowina 19 Bulgaria | Bulgarie | Bulgarien 21 Croatia | Croatie | Kroatien 23 Cyprus | Chypre | Zypern 25 Czech Republic | République tchèque | Tschechische Republik 27 Denmark | Danemark | Dänemark 29 England | Angleterre | England 31 Estonia | Estonie | Estland 33 Faroe Islands | Îles Féroé | Färöer-Inseln 35 Finland | Finlande | Finnland 37 France | France | Frankreich 39 Georgia | Géorgie | Georgien 41 Germany | Allemagne | Deutschland 43 Gibraltar | Gibraltar | Gibraltar 45 Greece | Grèce | Griechenland 47 Hungary | Hongrie | Ungarn 49 Iceland | Islande | Island 51 Israel | Israël | Israel 53 Italy | Italie | Italien 55 Kazakhstan | Kazakhstan | Kasachstan 57 Kosovo | Kosovo | Kosovo 59 Latvia | Lettonie | Lettland 61 Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein 63 Lithuania | Lituanie | Litauen 65 Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Luxemburg 67 Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | ARY -

F.C. København–Vejle Boldklub | 13

F.C. København–Vejle Boldklub | 13. april 2009 | klokken 17.30 | PARKEN Tre udvisninger Carsten Hemmingsen har fået F.C. København–Vejle to udvisninger mod Vejle, mens Kim Madsen en enkelt gang er 24. kamp mod Vejle os vinde 3–0. Den tidligere blevet præsenteret for det røde Det er 24. gang at vi møder rekord var fra maj 2002, hvor kort. Vi har endvidere fået 38 Vejle og alle hidtidige møder har 17.269 tilskuere så os vinde gule kort. været superligakampe. 11 af 2–1. Tilskuerrekorden i Vejle kampene er spillet i København, er på 8.545 og er fra efteråret Sidste nederlag mens vi 12 gange har været på 2008. Vores sidste nederlag mod besøg i Vejle. Vejle fandt sted i april 2000 og Velkommen tilbage det var en sprudlende Erik Bo 13 sejre i PARKEN … Andersen (Røde Romario!), De 23 kampe mod Vejle er endt der drev gæk med os, da han med 13 sejre, fire uafgjorte og Vi kan i dag sige goddag og scorede hattrick i Vejles 4–1 seks nederlag. De resultater velkommen til nogle gamle sejr. Siden da er der spillet otte giver et pointgennemsnit på kendinge. Udover vores udle- kampe og de er endt med seks 1,87 point pr. kamp. Vi har sco- jede Rasmus Würtz, finder vi sejre og to uafgjorte. ret 43 gange, mens det er ble- vores gamle forsvarsspiller vet til 23 mål til Vejle. Bora Zivkovic. Bora var med Tre mål i samme kamp til at vinde guld for os i 2003 Harald Brattbakk scorede tre Nu i hvide trøjer … og 2004 og nåede 57 kampe gange i 7–2 sejren i 2000. -

Merlin's Danish Faxe Kondi Ligaen 2000

www.soccercardindex.com Merlin’s Danish Faxe Kondi Ligaen 2000 checklist AB Akademisk Boldklub FC København Silkeborg INSERTS □1 Jan Bjur □46 Donatas Vencevicius □89 Morten Bruun □2 Nicolai Stokholm □47 Niclas Jensen □90 Lars Brøgger Klub Logo (Club Logos) □ □3 Jan Hoffmann □48 Todi Jónsson □91 Nocko Jokovic A1 AB Akademisk Boldklub □ □4 Lars Bo Larsen □49 Christian Lønstrup □92 Peter Kjær A2 AGF Aarhus □ □5 Jan Michaelsen □50 Kim Madsen □93 Thomas Røll Larsen A3 Brøndby □ □6 Alex Nielsen □51 Michael ‘Mio’ Nielsen □94 Peter Lassen A4 Esbjerg □ □7 Brian Steen Nielsen □52 David Nielsen □95 Henrik ‘Tømrer’ Pedersen A5 FC København □ □8 Allan Olsen □53 Thomas Rytter □96 Thomas Poulsen A6 Herfølge □ □9 Peter Rasmussen □54 Michael Stensgaard □97 Peter Sørensen A7 Lyngby □ □10 Peter Frank □55 Bo Svensson □98 Bora Zivkovic A8 OB Odense Boldklub □ □11 Abdul Sule □56 Thomas Thorninger A9 Silkeborg Vejle □A10 Vejle AGF Aarhus Herfølge □99 Erik Boye □A11 Viborg □12 Anders Bjerre □57 Thomas Høyer □100 Jens Madsen □A12 AAB Aalborg □13 Kenneth Christiansen □58 Lars Jakobsen □101 Kaspar Dalgas □14 Mads Jørgensen □59 John ‘Faxe’ Jensen □102 Calle Facius Faxe Kondi Superstars (Superstars) □15 Ken Martin □60 Kenneth Jensen □103 Jerry Brown □B1 Brian Steen Nielsen □16 Johnny Mølby □61 Kenneth Kastrup □104 Jesper Mikkelsen □B2 Peter Madsen □17 Bo Nielsen □62 Jesper Falck □105 Henrik Risom □B3 Kenneth Jensen □18 Michael Nonbo □63 Steven Lustü □106 Kent Scholz □B4 Søren Andersen □19 Mads Rieper □64 Henrik Lykke □107 Jesper Ljung □B5 Peter Lassen □20 Kenny Thorup -

Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2009

D ansk Boldspil-Union ansk · Årsberetning Årsberetning 2009 Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2009 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Henrik Vick Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk, Lise Fabricius m.fl. Redaktion slut 1. februar 2010 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 26,00 i forsendelse D ansk Boldspil-Union ansk · Årsberetning Årsberetning 2009 Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2009 Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Pia Schou Nielsen Layout/dtp DBU Grafisk Bettina Emcken Lise Fabricius Henrik Vick Fotos Anders & Per Kjærbye/Fodboldbilleder.dk, Lise Fabricius m.fl. Redaktion slut 1. februar 2010 Tryk og distribution Kailow Graphic Oplag 2.500 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 26,00 i forsendelse Dansk Boldspil-Union Årsberetning 2009 Indhold Dansk Boldspil-Union U/20-landsholdet . 53 Dansk Boldspil-Union 2009 . 4 U/19-landsholdet . 54 UEFA U21 – EM 2011 Danmark . 6 U/18-landsholdet . 56 Nationale relationer . 8 U/17-landsholdet . 58 Internationale relationer . 11 U/16-landsholdet . 60 Medlemstal . 14 Kvindelandsholdet . 62 Administrationen . 15 U/23-kvindelandsholdet . 63 Organisationsplan 2009 . 16 U/19-kvindelandsholdet . 64 Bestyrelsen og forretningsudvalget . 18 U/17-pigelandsholdet . 65 Udvalg . 19 U/16-pigelandsholdet .