Jharkhand - Past, Present & Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Jharkhand Movement: Regional Aspiration Has Fulfilled Yet

Indian J. Soc. & Pol. 06 (02):33-36 : 2019 ISSN: 2348-0084(P) ISSN: 2455-2127(O) HISTORY OF JHARKHAND MOVEMENT: REGIONAL ASPIRATION HAS FULFILLED YET AMIYA KUMAR SARKAR1 1Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, Adamas University Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA ABSTRACT This paper attempts to analyze the creation of Jharkhand as a separate state through the long developmental struggle of tribal people and the condition of tribal‟s in the post Jharkhand periods. This paper also highlights the tribal movements against the unequal development and mismatch of Government policies and its poor implementations. It is true that when the Jharkhand Movement gaining ground these non-tribal groups too became part of the struggle. Thus, Jharkhandi came to be known as „the land of the destitute” comprising of all the deprived sections of Jharkhand society. Hence, development of Jharkhand means the development of the destitute of this region. In reality Jharkhand state is in the grip of the problems of low income, poor health and industrial growth. No qualitative change has been found in the condition of tribal people as the newly born state containing the Bihar legacy of its non-performance on the development front. KEYWORDS: Regionalism, State Reconstruction, Jharkhand Movement INTRODUCTION 1859, large scale transference of tribal land into the hands of the outsiders, the absentee landlords has taken place in the The term Jharkhand literally means the land of forest, entire Jharkhand region, especially in Chotanagpur hill area. geographically known as the Chhotanagpur Plateau; the region is often referred to as the Rurh of India. Jharkhand was earlier The main concern of East India Company and the a part of Bihar. -

Development of Regional Politics in India: a Study of Coalition of Political Partib in Uhar Pradesh

DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL POLITICS IN INDIA: A STUDY OF COALITION OF POLITICAL PARTIB IN UHAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THB8IS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of ^IHloKoplip IN POLITICAL SaENCE BY TABRBZ AbAM Un<l«r tht SupMvMon of PBOP. N. SUBSAHNANYAN DEPARTMENT Of POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALI6ARH (INDIA) The thesis "Development of Regional Politics in India : A Study of Coalition of Political Parties in Uttar Pradesh" is an attempt to analyse the multifarious dimensions, actions and interactions of the politics of regionalism in India and the coalition politics in Uttar Pradesh. The study in general tries to comprehend regional awareness and consciousness in its content and form in the Indian sub-continent, with a special study of coalition politics in UP., which of late has presented a picture of chaos, conflict and crise-cross, syndrome of democracy. Regionalism is a manifestation of socio-economic and cultural forces in a large setup. It is a psychic phenomenon where a particular part faces a psyche of relative deprivation. It also involves a quest for identity projecting one's own language, religion and culture. In the economic context, it is a search for an intermediate control system between the centre and the peripheries for gains in the national arena. The study begins with the analysis of conceptual aspect of regionalism in India. It also traces its historical roots and examine the role played by Indian National Congress. The phenomenon of regionalism is a pre-independence problem which has got many manifestation after independence. It is also asserted that regionalism is a complex amalgam of geo-cultural, economic, historical and psychic factors. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Unrecognized Political Parties- Allotment of Common Symbol Under Para 1OB of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment)

JJuRGENTjJ ~-Bi?-1 fa! cl f=q cil Q G I f£I cb IJ.1, esc=cft -l-1 JI a,• ~ II a1 ifl cb., ~-lIcit I a-i 51 Icl i!.I q R-c1 -l., -lI i!.1 ~-l ~- 2236685- ~q~- 0771-2236684 email :- [email protected] w. a 9 ,ffl"R:"112 a 1 1 -2 a 1 4/ FJ9-3eo ~, RePafa 1 3ITT.1cf51 ~, -2.-i-2.-t en e1 Pai c1 re o1 ~, -l-f cH M (30 cJT O ) P.jq1S1~:-c11cf5-2-ta-rr "' 3na, ti!ailcl-2 o 1 4, 3HcirJI"' m ........-liui~-2."S<-r-cb~c.--.-a(::,,..., 3-lcf1l~a, "Q"Tl<f ~ cffi" 3il csi IB<i \.I cfl cf5 3il csi Cai cf5T \.I fa~ j ~ al Icl tj_ I c1"' 1 cb-2.-13-IT 3na=f ti!ai , c1- 2 o 1 4 cf.> ~ -lM -2."S<c{?a 3-t a-i 1~ a , "!l"l1<f ~ cffi" 3TI"-lcf Pai a f=q ai 3-11 ci, J, m \.I cfl cf5 3-11 csi cai cBT vT$ ~ , \.I cfl cf5 3-11 csi cai cf.> ~a -a1" 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. I, rec:iiicf5 2 7 R-2.-tcMJ-l, 2 o 1 3, "Q?I" -2-i&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. II, Rc:iiicf5 o 3 o16-ic1:fl, 2 o 1 4, "Q?I" -2-1&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. Ill, Raiicf5 1 o o1aic1:fl, 2 o 1 4"Q?I" -2-i&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. -

Agenda LTOA and Connectivity

Agenda for Connectivity and Long Term (Open) Access of IPP Generation Projects in Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal of Eastern Region 1.0 Applications for Connectivity and Long Term (Open) Access. Applications for grant of Connectivity and Long Term (Open) Access (LTOA / LTA) have been received by POWERGRID from the following applicants in Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal of Eastern Region. IPP generation projects in Jharkhand Complex. Sl. Project/Applicant Unit Size Ins. LTOA Time Applied for No. Capacity (MW)/Con Frame (MW) nectivity 1 Dumka (CESC) 2x300+1x600 1200 1100 2014-15 LTOA 2 ESSAR St-II 1x600 600 550 2013-14 LTOA Jindal Steel and 3 2x660 1320 1320 Jan,2015 Connectivity Power Ltd. (JSPL) Inland Power Mar’13 to 4 2x63+2x135 396 360 Connectivity Limited Mar‘16 Total 3516 3330 IPP generation projects in Bihar Complex. Sl. Project/Applicant Unit Size Ins. LTA/LTOA/C Time Applied for No. Capacity onnectivity Frame (MW) (MW) JAS Infrastructure Connectivity 1 2x660 1320 1200 Jan'14 Capital Pvt Ltd. & LTA Adhunik Power and 2 2x660 1320 1000 Dec' 14 Connectivity Natural Resources 3 Arissan Power Ltd 2x660 1320 1320 May’14 Connectivity Kanti Bijlee Connectivity 4 Utpadan Nigam 2x195 395 121.6 Nov’12 & LTA Limited India Power 5 2x660 1320 1320 Jul’15 Connectivity Corporation (Bihar)Ltd Total 5675 4961.6 IPP generation projects/Load Centre in West Bengal Complex. Sl. Project/Applicant Unit Size Ins. LTA/Conne Time Applied for No. Capacity ctivity Frame (MW) (MW) Himachal EMTA 1 2x250 500 500 Mar' 14 Connectivity Power Ltd 2 DPSC Ltd. -

State Fact Sheet Jharkhand

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16 State Fact Sheet Jharkhand International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) Mumbai 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the fourth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health and nutrition for India and each State / Union territory. NFHS-4, for the first time, provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of previous rounds of NFHS are generally retained and additional components are added from one round to another. In this round, information on malaria prevention, migration in the context of HIV, abortion, violence during pregnancy etc. have been added. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) or Biomarker component has been expanded to include measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose levels. NFHS-4 sample has been designed to provide district and higher level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour, husband’s background and woman’s work, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, and, domestic violence will be available at State and national level only. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India designated International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-4. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide essential data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. NFHS-4 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress in health sector the country has made over time. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Ramgarh District, Jharkhand State

भूजल सूचना पस्ु तिका रामगढ़ स्जला, झारखंड Ground Water Information Booklet Ramgarh District, Jharkhand State Open cast mines at Ramgarh district केन्द्रीय भसू िजल बो셍ड Central Ground water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल िंिाधन िंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) State Unit Office,Ranchi रा煍य एकक कायाालय, रााँची Mid-Eastern Region म鵍य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र Patna पटना सितंबर 2013 September 2013 भूजल सूचना पस्ु तिका रामगढ़ स्जला, झारखंड Ground Water Information Booklet Ramgarh District, Jharkhand State Prepared By रोज अनीता कू जूर (वैज्ञाननक ग ) Rose Anita Kujur (Scientist C) रा煍य एकक कायाालय, रााँची म鵍य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र,पटना State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid Eastern Region, Patna GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF RAMGARH DISTRICT, JHARKHAND STATE CONTENTS Sl.No. Details Page No. RAMGARH DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Administration 1 1.2 Drainage 4 1.3 Studies/Activities Carried Out By CGWB 4 2.0 HYDROMETEROLOGY 2.1 Rainfall 4 2.2 Climate 4 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES 3.1 Geomorphology 4 3.2 Soil 5 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO 4.1 Hydrogeology 5 4.2 Depth to Water Level 5 4.3 Water Level Trend 6 4.4 Aquifer Parameters 10 4.5 Ground Water Quality 10 4.6 Ground Water Resource 10 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 5.1 Ground Water Development 15 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS 15 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY 7.1 Mass Awareness Program(MAP) & Water 16 Management Programme(WMTP) by CGWB 8.0 AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWB / CGWA 16 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 16 Figure.No. -

District Survey Report of Stone District- Ramgarh

District Survey Report of Stone District- Ramgarh Prepared in accordance with Para 7 (iii) a of S.O.3611 (E) Dated 25th July 2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Notification August 2018 District Survey Report (Stone), Ramgarh District, Jharkhand CONTENT CHAPTER NO. Description Page No. Preamble 1 1. Introduction 2-3 2. Overview of mining activity in the district 4-5 3. General profile of the District 6-13 4. Geology of the district 14-15 5. Drainage of Irrigation pattern 16 6. Land Utilization Pattern of the District: Forest, Agricultural, 17 Horticultural, Mining etc. 7. Surface water and Ground water Scenario of the district 18-21 8. Rainfall of the District and Climatic Condition 22 9. Details of Mining leases in the district 23-30 10. Detail of Royalty or Revenue received in last 3 years 31 11. Detail of production of minor mineral in last 3 years 31 12. Mineral Map of the District 32 13. List of Letter of Intent(LOI) Holders in the District 33 14. Total Mineral Reserves Available in the District 33-34 15. Quality / Grade of Mineral Available in the District 34 16. Use of Mineral 34-35 17. Demand and Supply of the Mineral in the last three years 35 18. Mining Leases Marked on the Map of the District 36 19. Details of the area where there is a cluster of mining leases 36 20. Details of Eco-Sensitive Area in the District 37 21. Impact on the Environment due to mining activity 37-38 22. Remedial Measures to mitigate the impact of mining on the 39 Environment 23. -

Unit 20 National and Regional Parties

UNIT 20 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL PARTIES Structure 20.0 Objectives 20.1 Introduction 20.2 Meanings of a National and a Regional Party 20.3 National Parties 20.3.1 The Congress (I) 20.3.2 The Bharatiya ~anataParty 20.3.3 The Communist Parties 20.3.4 The Bahujan Samaj Party 20.4 The Regional Parties 20.4.1 The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and The All lndia Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) 20.4.2 The Shiromani Akali Dal 20.4.3 The National Conference 20.4.4 The Telugu Desam Party 20.4.5 The Assam Gana Parishad 20.4.6 The Jharkhand Party 20.5 Let Us Sum Up 20.6 Some Useful Books 20.7 Answers to Clieck Your Progress Exercises 20.0 OBJECTIVES 'This unit deals with the national and regional political parties in India. After going through this unit, you will be able to: Know tlie meanings of the regional and national political parties; Understand tlieir ideologies, social bases and the organisational structures; and Their significance in the politics and society of our country. 20.1 INTRODUCTION Political parties play cruciaT role in the functioning of Indian democracy. Democratic systems can not fulictioli in the absence of political parties. They work as link between state and people. Political parties contest elections and aim at capturing political power. They function as a link between people and government in a repre- sentative democracy. If a political party fails to form government, it sits in opposition. The role of the opposition party is to expose the weaknesses of the ruling party in order to strengthen tlie democratic processes. -

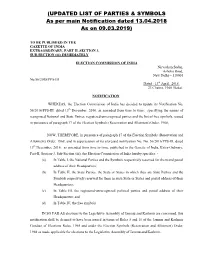

UPDATED LIST of PARTIES & SYMBOLS As Per Main Notification Dated 13.04.2018 As on 09.03.2019

(UPDATED LIST OF PARTIES & SYMBOLS As per main Notification dated 13.04.2018 As on 09.03.2019) TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY, PART II, SECTION 3, SUB-SECTION (iii) IMMEDIATELY ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 No.56/2018/PPS-III Dated : 13th April, 2018. 23 Chaitra, 1940 (Saka). NOTIFICATION WHEREAS, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2016/PPS-III, dated 13th December, 2016, as amended from time to time, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968; NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid notification No. No. 56/2016/PPS-III, dated 13th December, 2016, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extra-Ordinary, Part-II, Section-3, Sub-Section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies: - (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. IN SO FAR AS elections to the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir are concerned, this notification shall be deemed to have been issued in terms of Rules 5 and 10 of the Jammu and Kashmir Conduct of Elections Rules, 1965 and under the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968 as made applicable for elections to the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. -

The Legislative Assembly of Bihar

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1990 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF BIHAR ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 - 2 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 13 -14 6. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters 15 Votes Polled and Polling Stations 7. Woman Candidates 16 - 23 8. Constituency Data Summary 24 - 347 9. Detailed Result 348 - 496 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 1990 to the Legislative Assembly of BIHAR LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP BHARTIYA JANATA PARTY 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 4 . ICS(SCS) INDIAN CONGRESS (SOCIALIST-SARAT CHANDRA SINHA) 5 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 6 . JD JANATA DAL 7 . JNP(JP) JANATA PARTY (JP) 8 . LKD(B) LOK DAL (B) STATE PARTIES 9 . BSP BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY 10 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOC 11 . IML INDIAN UNION MUSLIM LEAGUE 12 . JMM JHARKHAND MUKTI MORCHA 13 . MUL MUSLIM LEAGUE REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 14 . ABSP AKHIL BAHARTIYA SOCIALIST PARTY 15 . AMB AMRA BANGALEE 16 . AVM ANTHARRASTRIYA ABHIMANYU VICHAR MANCH 17 . AZP AZAD PARTY 18 . BBP BHARATIYA BACKWARD PARTY 19 . BDC BHARAT DESHAM CONGRESS 20 . BJS AKHIL BHARATIYA JANA SANGH 21 . BKUS BHARATIYA KRISHI UDYOG SANGH 22 . CPI(ML) COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST-LENINIST) 23 . DBM AKHIL BHARATIYA DESH BHAKT MORCHA 24 .