Artemisia Gentileschi's Revolutionary Self-Portrait As The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI E Il Suo Tempo

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI e il suo tempo Attraverso un arco temporale che va dal 1593 al 1653, questo volume svela gli aspetti più autentici di Artemisia Gentileschi, pittrice di raro talento e straordinaria personalità artistica. Trenta opere autografe – tra cui magnifici capolavori come l’Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto del Wadsworth Atheneum di Hartford, la Giuditta decapita Oloferne del Museo di Capodimonte e l’Ester e As- suero del Metropolitan Museum di New York – offrono un’indagine sulla sua carriera e sulla sua progressiva ascesa che la vide affermarsi a Firenze (dal 1613 al 1620), Roma (dal 1620 al 1626), Venezia (dalla fine del 1626 al 1630) e, infine, a Napoli, dove visse fino alla morte. Per capire il ruolo di Artemisia Gentileschi nel panorama del Seicento, le sue opere sono messe a confronto con quelle di altri grandi protagonisti della sua epoca, come Cristofano Allori, Simon Vouet, Giovanni Baglione, Antiveduto Gramatica e Jusepe de Ribera. e il suo tempo Skira € 38,00 Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo Roma, Palazzo Braschi 30 novembre 2016 - 7 maggio 2017 In copertina Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta che decapita Oloferne, 1620-1621 circa Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1597 Virginia Raggi Direzione Musei, Presidente e Capo Ufficio Stampa Albino Ruberti (cat. 28) Sindaca Ville e Parchi storici Amministratore Adele Della Sala Amministratore Delegato Claudio Parisi Presicce, Iole Siena Luca Bergamo Ufficio Stampa Roberta Biglino Art Director Direttore Marcello Francone Assessore alla Crescita -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

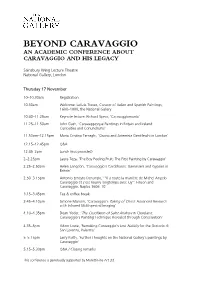

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

Artemisia Gentileschi : the Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-13-2010 Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar Deborah Anderson Silvers University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Silvers, Deborah Anderson, "Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3588 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Artemisia Gentileschi : The Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar by Deborah Anderson Silvers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Naomi Yavneh, Ph.D. Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 13, 2010 Keywords: Baroque, Susanna and the Elders, self referential Copyright © 2010, Deborah Anderson Silvers DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Fon Silvers. Nearly seven years ago, on my birthday, he told me to fulfill my long held dream of going back to school to complete a graduate degree. He promised to support me in every way that he possibly could, and to be my biggest cheerleader along the way. -

March 30, 2021 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Getty Museum Acquires

DATE: March 30, 2021 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Getty Museum Acquires Recently Rediscovered Painting by Artemisia Gentileschi Lucretia, About 1627, Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593- c.1654) Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Museum today announced the acquisition of a major work by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1654), the most celebrated woman painter of 17th-century Italy. Recently rediscovered after having been in private collections for centuries, the painting represents the artist at the height of her expressive powers, and demonstrates her ambition for depicting historical subjects, something that was virtually unprecedented for a female artist in her day. The subject, which Gentileschi painted several times over the course of her career, no doubt had very personal significance for her: like Lucretia, the Roman heroine who took her own life after having been raped, Artemisia had experienced sexual violence as a young woman. In this painting Lucretia emerges from the shadows, eyes cast heavenward, head tilted back, breasts bare, at the moment before she plunges a dagger into her chest. “Although renowned in her day as a painter of outstanding ability, Artemisia suffered from the long shadow cast by her more famous and celebrated father Orazio Gentileschi (of whom the Getty has two major works, Lot and His Daughters and the recently acquired Danaë and the Shower of Gold),” said Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “A thorough reassessment of her place in baroque art had to wait until the late 20th century, since when she has become one of the most sought-after painters of the 17th century. -

Preti-Cananea Dossier

Gallerie Nazionali Barberini Corsini Direttrice Flaminia Gennari Santori LA CANANEA RESTAURATA Nuove scoperte su Mattia e Gregorio Preti Roma, Palazzo Barberini 19 novembre 2020 – 2 maggio 2021 Mostra a cura di Alessandro Cosma, Yuri Primarosa DUE CALABRESI A ROMA Nella primavera del 1632, quando guida e di “procacciatore di commesse”, introducendo Mattia è documentato per la prima volta a Roma assieme a suo fratello nei circuiti del mercato e dei collezionisti, e nelle grazie di po- Gregorio (1603-1672), Mattia Preti (1613-1699) era un giovane tenti famiglie romane come i Barberini, i Rospigliosi e i Colonna. di belle speranze e qualche fortuna, innamorato dei grandi del Ricorda a questo proposito Sebastiano Resta (1635-1714) che suo tempo: Caravaggio, Ribera, Lanfranco e Guercino. Probabil- Gregorio «per tirarlo avanti e mantenerlo alla pittura si mise mente i due calabresi erano giunti nella città papale dalla natia anche a lavorare per bottegari, che allora erano ricchi»: una Taverna – piccolo borgo alle pendici della Sila – già nel 1624, testimonianza importante che mette in evidenza l’attenzione in tempo per assistere agli ultimi bagliori della pittura cara- riservata dal fratello maggiore alla formazione di Mattia. vaggesca e ai primi fuochi di quella barocca. Nei due decenni successivi, del resto, il linguaggio caravaggesco e i suoi temi IL TALENTO E IL MESTIERE Del resto, quella di Gregorio è una tipici (concerti, buone venture, scene di osteria...) continuarono pittura discontinua nei risultati che mostra spesso inclinazioni a ispirare i due artisti: uno sguardo “retrospettivo” che, eviden- culturalmente attardate e che ripropone in più occasioni schemi temente, trovava ancora degli estimatori nella Roma di quegli e modelli precedenti. -

The Twentieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia” Britiany Daugherty University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, Art, Art History and Design, School of School of Art, Art History and Design Spring 4-20-2015 Between Historical Truth and Story-Telling: The Twentieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia” Britiany Daugherty University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Design Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Daugherty, Britiany, "Between Historical Truth and Story-Telling: The wT entieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia”" (2015). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 55. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BETWEEN HISTORICAL TRUTH AND STORY-TELLING: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FABRICATION OF “ARTEMISIA” by Britiany Lynn Daugherty A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Marissa Vigneault Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2015 BETWEEN HISTORICAL TRUTH AND STORY-TELLING: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FABRICATION OF “ARTEMISIA” Britiany Lynn Daugherty, M.A. -

Press Release

PRESS Press Contact Rachel Eggers Associate Director of Public Relations [email protected] RELEASE 206.654.3151 AUGUST 19, 2019 FLESH AND BLOOD: ITALIAN MASTERPIECES FROM THE CAPODIMONTE MUSEUM OPENS AT SEATTLE ART MUSEUM OCTOBER 17, 2019 Rare opportunity to see major artworks by Artemisia Gentileschi, El Greco, Raphael, Jusepe de Ribera, Titian, and more SEATTLE, WA – The Seattle Art Museum presents Flesh and Blood: Italian Masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum (October 17, 2019–January 26, 2020), featuring 40 Renaissance and Baroque works of art (39 paintings and one sculpture) drawn from the collection of one of the largest museums in Italy. Traveling from the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples, the exhibition offers a rare opportunity to see works by significant Italian, French, and Spanish artists who worked in Italy including Artemisia Gentileschi, El Greco, Parmigianino, Raphael, Guido Reni, Jusepe de Ribera, Titian, and more. The Capodimonte Museum is a royal palace built in 1738 by Charles of Bourbon, King of Naples and Sicily (later King Charles III of Spain). The core of the collection is the illustrious Farnese collection of antiquities, painting, and sculpture, formed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and inherited by Charles of Bourbon. Italian and Spanish masterpieces of the Baroque period, grounded in realism and produced in Naples, build on this foundation. The Farnese collection traces a century of creativity, inspiration, and a constant search for beauty, followed by masterpieces of the Baroque era characterized by grandeur, dramatic realism, and theatricality. This exhibition marks the first time that this many works from the Capodimonte Museum will travel together at the same time. -

Newly Discovered Artemisia Gentileschi Painting Sells for €2.4M

AiA Art News-service Newly discovered Artemisia Gentileschi painting sells for €2.4m at auction in Paris Self-portrait as Saint Catherine, another woman who resisted, achieves record price for the artist SARAH P. HANSON 19th December 2017 23:28 GMT Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine by Artemisia Gentileschi sold at Drouot in Paris on 19 December for €2,360,600, an artist record A previously unknown Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine by the Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi sold at Drouot in Paris on 19 December for an artist record of €2,360,600 (€1.850m at the hammer, against an estimate of €300,000-€400,000). The work, which dates from the same period (1614-16) as another Saint Catherine picture by the artist held by the Uffizi, was discovered by auctioneer Christophe Joron-Derem and presented in his sale of European paintings. Lionised as an icon of feminist empowerment and artistic accomplishment since the 1970s, Gentileschi’s acclaim is now second only to that of Caravaggio among 17th-century Italian artists. A recent mini-survey of work at the Museo di Roma situating her among other painters of the era was a great success, but it also demonstrated that her existing works are inconsistent in quality. Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine, however, is easily the finest of several recently rediscovered paintings by Gentileschi, including Magdalen in Ecstasy, which was also found in France and sold at Sotheby's Paris in 2014 for $1,179,832, the artist’s previous record. Gentileschi was canny enough to exploit her singular fame as a female painter in the form of self-portraits in the guise of religious or allegorical figures (her most notable depiction by another artist is by her friend Simon Vouet, who portrayed her with her brushes and palette and a wonderfully commanding swagger). -

“The Lord Struck Him Down by the Hand of a Female!”: Seventeenth Century Artists Depicting Judith in the Renaissance

Journal of Mason Graduate Research Volume 3 Number 3 Year 2016 © George Mason University, Fairfax, VA ISSN: 2327-0764 Pages: 143-163 “The Lord Struck Him Down by the Hand of a Female!”: Seventeenth Century Artists Depicting Judith in the Renaissance TINA M. DELIS George Mason University This paper explores seventeenth century artists’ interpretation of Judith and Holofernes, a story about a female who subverted the contemporary norms by defeating a male. Focusing on the Baroque artists Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Orazio Gentileschi, and Artemisia Gentileschi, the paper explores, through visual analysis, how each artist addressed the story’s reversal of gender roles their artwork. The Catholic Bible narrative of Judith is discussed along with two primary sources about gender roles that were widely read in the period. Additionally, the paper discusses how the Counter-Reformation and the Catholic Church’s assertive stance for the purpose of art affects how images of Judith are painted. The Story of Judith A woman wields a sword to behead a man to save her people. This event is at the heart of the story of Judith as told in the Catholic Bible. A virtuous woman goes against the male elders of her community to save her people from destruction. The repeated portrayals of the story of Judith in several mediums—prints, textiles, engravings, sculpture, and paintings—point to the story’s popularity. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many artists chose to portray the heroine, even though patriarchal hierarchy defined Renaissance society (Varriano 94). Reading the story of Judith and Holofernes in the context of the Renaissance era, the text clearly discloses intrinsic tensions of gender norms of the time. -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI: Baroque Trail Blazer by Mario Rapisarda

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI: Baroque Trail Blazer By Mario Rapisarda The first woman ever to achieve both fame and fortune as an artist, Artemisia Gentileschi overcame many hardships, including a violent rape and a shot-gun marriage, to become a respected 17th century Baroque painter and the darling of European royalty. HER EARLY LIFE She was born in Rome on July 8, 1593, the daughter of a popular Tuscan painter, Orazio Gentileschi and his wife, Prudentia Montone. The first of five children and the only daughter, Artemisia lost two brothers and her mother by the age of 12. Her father decided to train Artemisia and her surviving brothers in his studio where he taught them to draw and mix paints. He also introduced them into his circle of working artists in Rome where Artemisia met the famed Baroque painter Michelangelo Caravaggio, whose dramatic use of light and shadow, the so-called chiaroscuro style, greatly influenced her work. By the time she was seventeen, Artemisia had already produced one of her most famous works, Susanna and the Elders (1610). A popular if racy subject with Renaissance and Baroque painters, it is based on an Old Testament story in the Book of Daniel in which Susanna, a young Jewish wife, is falsely accused of adultery by two old men because she refuses their sexual advances. Brought to trial, she is condemned to death, but saved by the young prophet Daniel (of the lions’ den fame), who exposes the two old men as liars, resulting in their execution. The painting’s subject is eerily prophetic because in 1612, two years after Artemisia completed it, her father accused Agostino Tassi, another painter, of raping her.