The Merlot Ticino Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have Some Madera, M'dear

HAVE SOME MADERA, M’DEAR Story and photos by John Blanchette Quiet lanes flow through the Madera Wine Trail It was the July 4th weekend and I was headed into the Central Valley to visit Madera County and one of California’s oldest wine growing areas. The San Joaquin Valley can be blistering hot this time of year and I certainly wasn’t disappointed. Temperatures soared to 105 degrees. As my car drove on Route 99, slicing through this wide, flat and fertile plane that stretches over 200 miles between Bakersfield and Stockton, crops and livestock passed my window like an expanded grocery market. Table grapes, sugar cane, corn, tomatoes, citrus, peaches, plums, apricots, strawberries, watermelons, pistachio, pecan, Cattle range in the shadow of Giant Eucalyptus www.aiwf.org SAVOR THIS • OCTOBER 2010 15 almond, pomegranate and walnut trees, pigs, cattle, sheep, and dairy cows, etc. in abundance. One farmer told me that the topsoil is unlimited and all they need is water to grow their crops. And that’s a major problem. The current draught has caused some farmers to let their fields go fallow. The city of Madera, located 38 miles from the geographic center of California, derives its name from the Spanish word for wood, which was harvested in the Yosemite Valley foothills and shipped from Madera to build San Francisco and other area communities in the 1800s. The Madeira wine produced on the Portuguese Vineyards run to the mountains island made famous by the bawdy English tune I was off to confirm this as I explored the Madera “Have Some Madeira, m’Dear” is just a coincidence. -

Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 1 Article 7 2020 Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California Tony Quinn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Quinn, Tony (2020) "Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quinn: Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California by Tony Quinn “The southernmost of Switzerland’s twenty-six cantons, the Ticino, may speak Italian, sing Italian, eat Italian, drink Italian and rival any Italian region in scenic beauty—but it isn’t Italy,” so writes author Paul Hofmann1 describing the one Swiss canton where Italian is the required language and the cultural tie is to Italy to the south, not to the rest of Switzerland to the north. Unlike the German and French speaking parts of Switzerland with an identity distinct from Germany and France, Italian Switzerland, which accounts for only five percent of the country, clings strongly to its Italian heritage. But at the same time, the Ticinese2 are fully Swiss, very proud of being part of Switzerland, and with an air of disapproval of Italy’s ever present government crises and its tie to the European Union and the Euro zone, neither of which Ticino has the slightest interest in joining. -

The Italian Swiss DNA

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 52 Number 1 Article 2 2-2016 The Italian Swiss DNA Tony Quinn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Quinn, Tony (2016) "The Italian Swiss DNA," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 52 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol52/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quinn: The Italian Swiss DNA The Italian Swiss DNA by Tony Quinn* DNA testing is the new frontier in genealogical research. While the paper records of American and European churches and civil bodies are now generally available on line, DNA opens a new avenue of research into the period well before the advent of written records. And it is allowing people to make connections heretofore impossible to make. Recent historical examples are nothing short of amazing. When the bodies thought to be the last Russian Czar and his family, murdered in 1918, were discovered, a 1998 test using the DNA of Prince Philip proved conclusively that the bodies were indeed the Czar and his family. That is because Prince Philip and the Czarina Alexandra shared the same maternal line, and thus the same mitochondrial DNA. Even more remarkable was the "king in the car park," a body found under a parking lot in England thought to be King Richard III, killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. -

PCP Forum 31/2018: Viticulture and Protection of Cultural Property

PCP Forum 31/2018: Viticulture and Protection of Cultural Property Jeanne Berthoud: Editorial. Viticulture and Protection of cultural property ......................................... 2 Anne-France Jaccottet: Dionysus – the God of wine… and more besides .............................................. 3 Debora Schmid: Viticulture in ancient Roman provinces – evidence from Augusta Raurica ................. 4 Heidi Lüdi Pfister: Viticulture in Switzerland .......................................................................................... 4 Peter Schumacher: Professional viticulture and winemaking qualifications .......................................... 4 Sabine Carruzzo-Frey, Isabelle Raboud-Schüle: The Fête des Vignerons – a Swiss living tradition ....... 5 Gilbert Coutaz: The Fête des Vignerons becomes a work of literature .................................................. 5 David Vitali: The Fête des Vignerons: the first Swiss entry on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Oliver Martin: The Lavaux vineyards – a UNESCO world heritage site ................................................... 6 Marcia Haldemann: Characteristic and typological winegrowing areas on the ISOS ............................. 6 Hanspeter Schneider: Along the ViaValtellina ........................................................................................ 7 Hans Schüpbach: A new life for the "Bergtrotte" -

Beverages Our Recommendations

BEVERAGES OUR RECOMMENDATIONS WHITE WINES FÉCHY GRAND CRU AOC A classic Chasselas: soft, well-rounded and very popular with our guests. PRODUCER: DOMAINE DE FISCHER-HAMMEL, ROLLE – LA CÔTE – VAUD – SWITZERLAND GRAPE VARIETY: CHASSELAS 7.5DL: CHF 45.– PINOT GRIGIO DELLE VENEZIE DOC Mineral notes, pleasant acidity, intense yellow fruit. Popular as a meal accompaniment or an aperitif. PRODUCER: TERRE VENETE, ORMELLE – VENETIEN – ITALY GRAPE VARIETY: PINOT GRIGIO 7.5DL: CHF 43.– RED WINES MERLOT TI DOC MERLOT A typical Merlot from canton Ticino – soft with a fresh finish. PRODUCER: CANTINA LUISONI, CAPOLAGO – SOTTOCENERI – TESSIN – SWITZERLAND GRAPE VARIETY: MERLOT 7.5DL: CHF 46.– TEMPRANILLO VDT Elegant and ripe fruit with well-incorporated tannins and a pleasantly spicy, medium finish. PRODUCER: DEL CAMPO, CORRAL DE ALMAGUER – CASTILLA – SPAIN GRAPE VARIETY: TEMPRANILLO 7.5DL: CHF 44.– All prices are in Swiss francs (CHF) and include VAT. 2 SPARKLING WINES CHAMPAGNES ORIGIN 7.5 DL PREMIER BRUT CHARDONNAY/PINOT NOIR/PINOT MEUNIER France 109 Roederer, Reims BLANC DE BLANCS VINTAGE BRUT CHARDONNAY France 140 Roederer, Reims CHAMPAGNES ROSÉ ROSÉ VINTAGE BRUT PINOT NOIR/CHARDONNAY France 139 Roederer, Reims FRANCIACORTA & PROSECCO FRANCIACORTA BRUT DOCG CHARDONNAY/PINOT NOIR Italy 80 La Montina, Monticelli Brusati – Brescia PROSECCO CASA DEI FARIVE BRUT DOC GLERA Italy 49 Cantine Vedova, Valdobbiadene – Treviso All prices are in Swiss francs (CHF) and include VAT. 3 WHITE WINES SWITZERLAND 7.5 DL DÉZALEY AOC CHASSELAS 62 Dizerens, Lutry – Lavaux – Vaud Intense aroma structure that is typical of the variety. This wine excels with mineral and fruit notes on the palate. PETITE ARVINE AOC 51 Rouvinez, Sierre – Valais An autochthonous grape variety from canton Valais. -

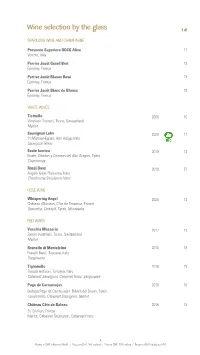

1 Dl SPARKLING WINE and CHAMPAGNE Prosecco Superiore

1 dl SPARKLING WINE AND CHAMPAGNE Prosecco Superiore DOCG Alice 11 Veneto, Italy Perrier Jouët Grand Brut 19 Épernay, France Perrier Jouët Blason Rosé 23 Épernay, France Perrier Jouët Blanc de Blancs 33 Épernay, France WHITE WINES Ticinello 2020 10 Vinattieri Ticinesi, Ticino, Switzerland Merlot Sauvignon Lahn 2020 11 St.Michael-Eppan, Alto Adige, Italy Sauvignon Blanc Enate barrica 2019 12 Enate, Viñedos y Crianzas del Alto Aragon, Spain Chardonnay Rossj Bass 2019 27 Angelo Gaja, Piemonte, Italy Chardonnay,Sauvignon blanc ROSÉ WINE Whispering Angel 2020 12 Château d’Esclans, Côte de Provence, France Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah, Mourvèdre RED WINES Vecchia Masseria 2017 13 Zanini-Vinattieri, Ticino, Switzerland Merlot Brunello di Montalcino 2015 16 Fratelli Banfi, Toscana, Italy Sangiovese Tignanello 2018 29 Tenuta Antinori, Toscana, Italy Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet franc, Sangiovese Pago de Carraovejas 2018 16 Bodega Pago de Carraovejas, Ribera del Duero, Spain Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot Château Côte de Baleau 2016 15 St. Emilion, France Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc A Preise in CHF inklusive MwSt / Prezzi in CHF, IVA inclusa / Prix en CHF, TVA inclue / Prices in CHF including VAT 3.75 dl 7.5 dl 45 Prosecco Superiore DOCG Alice 69 Veneto, Italy 32 Donatsch Crémant 95 Malans,Switzerland 8 Ferrari Perlè Brut 122 Trentino, Italy 21 Villa Emozioni DOCG 2015 97 Franciacorta, Italy 6 Noir Spumante 72 Ticino, Switzerland 3 Donna Cara Satèn 95 Franciacorta,M.Antinori, Lombardia, Italy 7.5 dl 9 Perrier Jouët Grand Brut -

Canada-EU Wine and Spirits Agreement

6.2.2004 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 35/3 AGREEMENT between the European Community and Canada on trade in wines and spirit drinks THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, hereafter referred to as ‘the Community', and CANADA, hereafter jointly referred to as ‘the Contracting Parties', RECOGNISING that the Contracting Parties desire to establish closer links in the wine and spirits sector, DESIROUS of creating more favourable conditions for the harmonious development of trade in wine and spirit drinks on the basis of equality and mutual benefit, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: TITLE I — ‘labelling' shall mean any tag, brand, mark, pictorial or other descriptive matter, written, printed, stencilled, marked, embossed or impressed on, or attached to, a INITIAL PROVISIONS container of wine or a spirit drink, Article 1 — ‘WTO Agreement' refers to the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organisation, Objectives 1. The Contracting Parties shall, on the basis of — ‘TRIPs Agreement' refers to the Agreement on trade-related non-discrimination and reciprocity, facilitate and promote aspects of intellectual property rights, which is contained trade in wines and spirit drinks produced in Canada and the in Annex 1C to the WTO Agreement, Community, on the conditions provided for in this Agreement. 2. The Contracting Parties shall take all reasonable measures — ‘1989 Agreement' refers to the Agreement between the to ensure that the obligations laid down in this Agreement are European Economic Community and Canada concerning fulfilled and that the objectives set out in this Agreement are trade and commerce in alcoholic beverages concluded on attained. 28 February 1989. Article 2 2. -

Cut Wine List Wines by the Glass

CUT WINE LIST WINES BY THE GLASS WINES MADE WITH PASSION AND SOURCED WITH CARE. Our new selection of wines is focused on handcrafted boutique wineries from all around England. Our goal is to support energetic and devoted wine makers, discovering hidden gems with a sustainable approach. 125ML CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING Davenport, Limney Estate, Kent, UK, 2014 19 Furleigh Estate, Classic Cuvée, Dorset, UK, 2014 15 R de Ruinart, Brut, Champagne, France, NV 28 Ruinart Blanc de Blancs, Champagne, France, NV 32 CHAMPAGNE ROSÉ Furleigh Estate, Rosé, Dorset, UK, NV 19 Tillingham Wines, Rosé Pet Nat, East Sussex, UK, 2018 17 Ruinart Rosé, Champagne, France, NV 36 175ML WHITE Bacchus, Davenport Horsmoden, Kent, UK, 2018 17 Chenin Blanc, Testalonga Baby Bandito, South Africa, 2019 16 Altesse Blend, Domaines des 13 Lunes, Ami-Amis, Savoie, France, 2018 22 Chardonnay, Domaine Langoureau, Saint-Aubin 1er Cru Le Champlot, Burgundy, 34 France, 2015 WOLFGANG PUCK SELECTION Chardonnay, Wolfgang Puck, California, USA, 2016 18 ROSÉ Pinot Noir, Family Shiner, Woodchester Valley, Cotswolds, UK, 2018 14 Grenache Blend, Domaine de Cala Préstige, Provence, France, 2018 19 RED Pinot Noir, Davenport Estate, Diamonds Fields, Kent, UK, 2018 19 Syrah, Yves Cuilleron, Les Vignes D’a Côté, Rhône Valley, France, 2018 18 Merlot, Moulin de Duhart, Pauillac, Bordeaux, France, 2016 30 WOLFGANG PUCK SELECTION Pinot Noir, Wolfgang Puck, Master Lot Blend, California, USA, 2016 17 Cabernet Sauvignon, Wolfgang Puck, Master Lot Blend, California, USA, 2017 18 SOMMELIER RECOMMENDATIONS -

Ticino Wine-Growing Area

Rhône WINE AND Léman CULTURAL EVENING TICINO th Locarno Monday, July 15 2019 Bellinzona Lugano TICINO WINE-GROWING AREA During this evening, you will be able to discover the six Swiss wine-growing regions. Through their local products and their emblematic wines, you will be immersed in the heart of Swiss wine-growing. Speeches and folk entertainments are also on the agenda. 19:00 Welcome Drink Traditional alphorns’ show 19:15 Welcoming words 19:30 Eliana Bürki’s show Opening of wine tasting 20:15 Opening of terroir products degustation 21:00 Eliana Bürki’s show TICINO TERROIR Fresh goat cheese, olive tapenade and sundried tomatoes on olive bread Burrata and tomato tartar verrine Vitello tonato skewer Polenta gratin in pistou sauce Saffron risotto from Ticino served in a Grana Padano cheese loaf Sweet chestnut vermicelli with meringues and double cream TICINO WINES Chardonnay Merlot Merlot Agra Collina d’oro, Carato - 2016 La Trosa - 2016 Cantina Pelossi, Vini & Distillati Angelo Cantina Sociale Lugano (TI) Delea, Losone (TI) Mendrisio (TI) Merlot Merlot Bucaneve - 2018 Moncucchetto - 2016 CAGI Giubiasco (TI) Lugano (TI) Ticinowine was born in 1984 as «Proviti». Since 1° January 2005 Ticinowine has been integrated into the «Interprofession of Ticino Vine and Wine (IVVT)», which includes all the actors of the cantonal production chain. Over the time it has grown up and has been able to gain enviable visibility in the national and foreign market, often in close collaboration with similar and complementary sectors. Ticinowine mainly focuses on the promotion of Ticino’s wine production and its image. The association has about 250 members, who are responsible for the production of over 2’700 skilled and passionate wine growers. -

Monsecco – Alto Piemonte; Uva Rara, Vespolina & Croaɵna

Monsecco – Alto Piemonte; Uva Rara, Vespolina & CroaƟna Monsecco is one of the best kept secrets of Neal Rosenthal's very strong porolio. Neal has been a long‐me champion of Piedmont's hinterlands: Ferrando's legendary Carema is a monument to his passion for the area and Neal’s new involvement with the family with vineyard purchases. It also underscores his ability to discover great producers in obscure places. Though it's worth remembering that what's obscure today might not have been obscure in the past; wine writers are quick to point out that in the 19th century Ganara enjoyed greater renown than Barolo or Barbaresco. In other words: This is very serious terroir for Nebbiolo. Monsecco was an old estate that made great wine in the 1960s and then became defunct. Happily, a new generaon descended from Lorenzo Zanea has revived the estate and now cras the finest wines in the Colline Novaresi, and Ganara DOCs using the same tradional methods. This region is defined by Nebbiolo, but the supporng players are what our focus is here. In “A Trip to Alto Piemonte” ‐ Eric Asimov in The New York Times recently had a great write‐up on Nebbiolo from the “other” parts of Piedmont (meaning not Barolo or Barbaresco), the vast majority of the wines covered by the arcle are from a region called Alto Piemonte, which is basically higher up in the foothills of the Alps north of Barolo/Barbaresco. It is one of the most interesng wine regions in the world. We are fascinated by it, and have a selecon of wines from the region. -

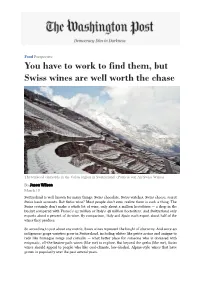

You Have to Work to Find Them, but Swiss Wines Are Well Worth the Chase

Food Perspective You have to work to find them, but Swiss wines are well worth the chase The terraced vineyards in the Valais region in Switzerland. (Patricia von Ah/Swiss Wines) By Jason Wilson March 15 Switzerland is well known for many things: Swiss chocolate, Swiss watches, Swiss cheese, secret Swiss bank accounts. But Swiss wine? Most people don’t even realize there is such a thing. The Swiss certainly don’t make a whole lot of wine, only about a million hectoliters — a drop in the bucket compared with France’s 42 million or Italy’s 48 million hectoliters. And Switzerland only exports about 2 percent of its wine. By comparison, Italy and Spain each export about half of the wines they produce. So according to just about any metric, Swiss wines represent the height of obscurity. And since 40 indigenous grape varieties grow in Switzerland, including whites like petite arvine and amigne to reds like humagne rouge and cornalin — what better place for someone who is obsessed with enigmatic, off-the-beaten-path wines (like me) to explore. But beyond the geeks (like me), Swiss wines should appeal to people who like cool-climate, low-alcohol, Alpine-style wines that have grown in popularity over the past several years. “It’s a good time for alternative wine countries like Switzerland. There is a curiosity that I’ve never seen before,” said Gilles Besse, winemaker at Jean-René Germanier in the mountainous Valais region, where grapes grow close to some of the world’s best skiing, often at more than 2,000 feet above sea level. -

Swiss Wood in Wine Maturation in Switzerland & Ticino

MASTERCLASS: SWISS WOOD IN WINE MATURATION IN SWITZERLAND & TICINO With Gerhard Benninger of Tonnellerie Schuler, Alfred de Martin of Gialdi & Brivio and Gianfranco Chiesa of Vini Rovio TONNELLERIE SCHULER ▪ Located in Canton Schwyz ▪ One of 4 cooperages in Switzerland – the 3rd largest (2nd smallest) ▪ Started producing barrels in 2000 - French & American oak from Seguin-Moreau, Swiss oak in 2003, mélèze (from Valais), chestnut, and acacia in 2007, Ticino oak production in 2015 ▪ 550 barrels produced/yr – 50% Swiss oak, 30% French oak, 20% others (chestnut, acacia, American oak, mélèze) ▪ 70% is 228L, 30% is 225L and 300L + vats up to 5,000 litres ▪ Schuler is the only producer in CH of Ticino oak and Ticino chestnut barrels ▪ Schuler also produces wine and buys other producers’ wines which are then matured and bottled at own facility and under own label SHORT HISTORY OF WOOD AGEING IN EUROPE & SWITZERLAND ▪ Wine was stored and transported in wood in Europe since the time of the Celts (circa 700 B.C.). Vessels looked very much like our present barrel ▪ Only local wood was used (it was impossible to transport ”foreign” wood at that time) ▪ Softer woods were used (spruce, fir, pine) – greater ease in handling. But in19th century, people realised that hard woods (e.g. oak) were more durable & improved the wine more ▪ In Austria, Germany and Switzerland, producers used large wooden casks of up to 250,000 L (90,000 L in CH) rather than small barrels ▪ Wood was not chosen for flavour components but for practicality/locality Hiedelberg Tun of 219,000 L ▪ In 1980s, French barriques started to be imported into Switzerland – the majority of producers now use them (Germany), circa 1751 ▪ More producers are now rediscovering local woods and experimenting with barrels of different toast levels WHERE SWISS OAK COMES FROM 5 Regions (lgt-smallest): 1) Neuenberg/Biel (Neuchâtel) 2) Schaffhausen (Aargau) - 30 km are 3) Romanshorn - (Constance/St.