Wonder in the Pedagogy of Antiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riddling at Table: Trivial Ainigmata Vs. Philosophical Problemata

Riddling at table: trivial ainigmata vs. philosophical problemata Autor(es): Beta, Simone Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra; Centro de Estudos Clássicos e Publicado por: Humanísticos URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/31982 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/978-989-8281-17-3_9 Accessed : 2-Oct-2021 03:11:33 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Symposion and Philanthropia in Plutarch Manuel Troster e Paula Barata Dias (eds.) IMPRENSA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA COIMBRA UNIVERSITY PRESS ANNABLUME Riddling at table: trivial ainigmata vs. philosophical problemata Riddling at table T RIVIAL AINIGMA T A V S . -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Wonder, Space, and Place in Pausanias' Periegesis

Axion Theas: Wonder, Space, and Place in Pausanias’ Periegesis Hellados by Jody Ellyn Cundy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Jody Ellyn Cundy 2016 Axion Theas: Wonder, Space, and Place in Pausanias’ Periegesis Hellados Jody Ellyn Cundy Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The Periegesis Hellados presents a description of the sites and sights of Roman Greece in ten carefully constructed books. These books present the fruits of author’s extensive travels and careful textual research over the course of several decades (between the 130’s and ca. AD 175-80) and compiled into a unified composite itinerary. There is no doubt that Pausanias travels through an “already written landscape,” and his travel experience is necessarily informed by and sometimes clearly motivated by his literary encounters. This project investigates Pausanias’ engagement with literary antecedents, with a particular focus on the antiquarian impulse to excerpt and compile anecdotes in thematic catalogues, which broadly resemble wonder-texts (paradoxographies). The organizing principle of these thematic catalogues contrasts with the topographical (spatial) structure of the frame narrative of the Periegesis. In part, this study aims to resolve the perceived tension between the travel account and the antiquarian mode in Pausanias’ project in order to show that they serve complementary rather than competing ends. Resolution of these competing paradigms allows in turn for a more coherent understanding of the Periegesis as unified subject. This study argues that wonder (thauma) is a unifying theme ii of Periegesis Hellados. -

Greek Word Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76517-6 - Galen: Psychological Writings Edited by P. N. Singer Index More information Greek word index Comprehensive word indexes are available in the modern editions of the Greek texts translated in this volume (though in the case of Capacities of the Soul, only in the recent edition of Bazou, not in that of Müller). The present index contains a selection of terms with their translations, referenced by page and line numbers of the edition used, and is intended to be of help in finding both the translation and the occurrences of technical or otherwise interesting terminology. For certain very commonly used terms (e.g. agathos, anthrōpos, psuchē), where no problem of translation arises, only a few passages are given by way of example; for terms of particular importance to the argument of the texts, most or all occur- rences have been listed. Compound verbs are listed under the main verbal form and adverbs under the corresponding adjective. ἀγαθός good Ind. 18,19; 20,13; 21,6 QAM ἀδιανόητος incomprehensible QAM 48,18 40,22 (Hesiod); 73,14; 74,5-11; τὰ ἀγαθά ἀδικεῖν harm QAM 74,15.17 (matters of) good Aff. Pecc. Dig. 42,11-19; ἀερώδης airy (substance) QAM 45,10 44,13 (with note); τὸ ἀγαθόν the good Ind. ἀήρ air QAM 45,11.23; 66,11 20,1.4 Aff. Pecc. Dig. 42,21; 43,9 QAM 73,17; ἀθάνατος immortal QAM 36,14; 38,4; 42,14 what someone enjoys Aff. Pecc. Dig. 24,14 ἀθυμεῖν be dispirited Aff. -

On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book Herbert Granger Wayne State University, [email protected]

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The ocS iety for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 4-24-2002 On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book Herbert Granger Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Granger, Herbert, "On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book" (2002). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 331. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/331 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THE NATURE OF HERACLITUS’ BOOK Herbert Granger Wayne State University (Comments Welcome) THE DISPUTE OYER HERACLITUS’ BOOK Antiquity credits Heraclitus with a single book (D. L. 9.5-6), but the nature, even the existence, of this ‘book’ remain disputed.1 The orthodoxy takes it to be a collection of independent aphorisms that at most Heraclitus grouped into loose associations under a few headings.2 Heraclitus did not lay out his thoughts sequentially or develop them in a continuous fashion, and thus he did not build one statement upon the other and drive steadily towards a conclusion or conclusions. Because Diels despaired of discerning any intrinsic order among Heraclitus’ fragments, he printed them largely in an alphabetical arrangement based on the names of the authors who preserved them. -

What Were Works Περὶ Βίων ?

Philologus 2016; 160(1): 59–83 Gertjan Verhasselt* What Were Works Περὶ βίων? A Study of the Extant Fragments DOI 10.1515/phil-2016-0004 Abstract: For a long time, the exact nature of Περὶ βίων literature and its relation to biography has been debated. Scholars have considered such works collections of biographies or philosophical treatises on the right way of life. This paper studies all extant fragments across various philosophical schools. Epicurus and Chrysippus seem to have given practical instructions on the right lifestyle. Clearchus, Dicaearchus and the imperial writers Timotheus and Seleucus, by contrast, took a more anecdotal approach. However, the fragments do not support a reconstruction of biographies in the sense of a description of the life of an individual from birth to death. The anecdotes in Clearchus were probably moralis- ing exempla. Moreover, not all biographical fragments of Dicaearchus necessarily belong to his work On Lives. I also argue that Περὶ βίων works were probably the ideal place for debate and polemic against competing schools. Keywords: Περὶ βίων, biography, philosophy, fragments 1 Introduction Biography emerged as a historiographical genre in the Hellenistic period. One type of work whose connection with this genre has often been debated is entitled Περὶ βίων (On Lives or On Ways of Life). Such works are attested for several Hellenistic philosophers: Xenocrates (F 2,12 Isnardi Parente), Heraclides Ponticus (F 1,87 Schütrumpf),1 Theophrastus (F 436,16 FHS&G), Strato (F 1,59 Sharples), Clearchus, Dicaearchus, Epicurus and Chrysippus (on the latter four, cf. infra). 1 Wehrli (1969a) 17–18; 72 attributed Diog. -

On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 4-24-2002 On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book Herbert Granger Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Granger, Herbert, "On the Nature of Heraclitus' Book" (2002). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 331. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/331 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THE NATURE OF HERACLITUS’ BOOK Herbert Granger Wayne State University (Comments Welcome) THE DISPUTE OYER HERACLITUS’ BOOK Antiquity credits Heraclitus with a single book (D. L. 9.5-6), but the nature, even the existence, of this ‘book’ remain disputed.1 The orthodoxy takes it to be a collection of independent aphorisms that at most Heraclitus grouped into loose associations under a few headings.2 Heraclitus did not lay out his thoughts sequentially or develop them in a continuous fashion, and thus he did not build one statement upon the other and drive steadily towards a conclusion or conclusions. Because Diels despaired of discerning any intrinsic order among Heraclitus’ fragments, he printed them largely in an alphabetical arrangement based on the names of the authors who preserved them. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

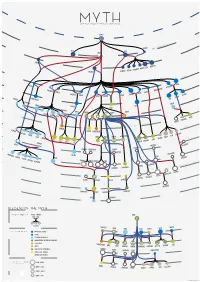

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

TSJCL Mythology

CONTEST CODE: 09 2012 TEXAS STATE JUNIOR CLASSICAL LEAGUE MYTHOLOGY TEST DIRECTIONS: Please mark the letter of the correct answer on your scantron answer sheet. 1. The myrtle and the dove are her symbols (A) Amphitrite (B) Aphrodite (C) Artemis (D) Athena 2. His wife left him and ran off to Troy with Paris; he was not happy about it and got some help (A) Agamemnon (B) Diomedes (C) Menelaus (D) Odysseus 3. This deity was the only one who worked; god of the Forge and Blacksmiths (A) Apollo (B) Hephaestus (C) Mercury (D) Neptune 4. He went searching for a bride and found Persephone (A) Aeacus (B) Hades (C) Poseidon (D) Vulcan 5. Half man, half goat, he was the patron of shepherds (A) Aeolus (B) Morpheus (C) Pan (D) Triton 6. He attempted to win the contest as Patron of Athens, but lost to Athena (A) Apollo (B) Hephaestus (C) Hermes (D) Poseidon 7. He performs Twelve Labors for his cousin as penance for crimes committed while mad (A) Aegeus (B) Heracles (C) Jason (D) Theseus 8. As punishment for opposing Zeus, he holds the Heavens on his shoulders (A) Atlas (B) Epimetheus (C) Oceanus (D) Prometheus 9. Son of Zeus, king of Crete, he ordered the Labyrinth built to house the Minotaur (A) Alpheus (B) Enipeus (C) Minos (D) Peleus 10. This wise centaur taught many heroes, including Achilles (A) Chiron (B) Eurytion (C) Nessus (D) Pholus 11. She was the Muse of Comedy (A) Amphitrite (B) Euphrosyne (C) Macaria (D) Thalia 12. She rode a white bull from her homeland to Crete and bore Zeus three sons (A) Danae (B) Europa (C) Leda (D) Semele 13.