Why Medication Is So Expensive, and What You Can Do About It Breakthrough Drugs for Rare Neurologic Diseases Are Staggeringly Expensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

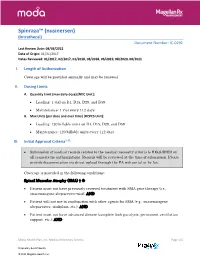

Spinraza™ (Nusinersen)

Spinraza™ (nusinersen) (Intrathecal) Document Number: IC-0291 Last Review Date: 08/03/2021 Date of Origin: 01/31/2017 Dates Reviewed: 01/2017, 02/2017, 01/2018, 08/2018, 06/2019, 08/2020, 08/2021 I. Length of Authorization Coverage will be provided annually and may be renewed. II. Dosing Limits A. Quantity Limit (max daily dose) [NDC Unit]: • Loading: 1 vial on D1, D15, D29, and D59 • Maintenance: 1 vial every 112 days B. Max Units (per dose and over time) [HCPCS Unit]: • Loading: 120 billable units on D1, D15, D29, and D59 • Maintenance: 120 billable units every 112 days III. Initial Approval Criteria1-12 • Submission of medical records related to the medical necessity criteria is REQUIRED on all requests for authorizations. Records will be reviewed at the time of submission. Please provide documentation via direct upload through the PA web portal or by fax. Coverage is provided in the following conditions: Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) † Ф • Patient must not have previously received treatment with SMA gene therapy (i.e., onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi); AND • Patient will not use in combination with other agents for SMA (e.g., onasemnogene abeparvovec, risdiplam, etc.); AND • Patient must not have advanced disease (complete limb paralysis, permanent ventilation support, etc.); AND Moda Health Plan, Inc. Medical Necessity Criteria Page 1/5 Proprietary & Confidential © 2021 Magellan Health, Inc. • Patient must have the following laboratory tests at baseline and prior to each administration*: platelet count, prothrombin time; activated -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT | Translating SCIENCE • Transforming LIVES OUR COMMITMENT Make Every Day Count at PTC, Patients Are at the Center of Everything We Do

20 YEARS OF COMMITMENT 2017 ANNUAL REPORT | Translating SCIENCE • Transforming LIVES OUR COMMITMENT Make every day count At PTC, patients are at the center of everything we do. We have the opportunity to support patients and families living with rare disorders through their journey. We know that every day matters and we are committed to making a difference. OUR SCIENCE Our scientists are finding new ways to regulate biology to control disease We have several scientific research platforms focused on modulating protein expression within the cell that we believe have the potential to address many rare genetic disorders. OUR PEOPLE Care for each other, our community, and for the needs of our patients At PTC, we are looking at drug discovery and development in a whole new light, bringing new technologies and approaches to developing medicines for patients living with rare disorders and cancer. We strive every day to be better than we were the day before. At PTC Therapeutics, it is our mission to provide access to best-in-class treatments for patients who have an unmet need. We are a science-led, global biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery, development and commercialization of clinically-differentiated medicines that provide benefits to patients with rare disorders. Founded 20 years ago, PTC Therapeutics has successfully launched two rare disorder products and has a global commercial footprint. This success is the foundation that drives investment in a robust pipeline of transformative medicines and our mission to provide access to best-in-class treatments for patients who have an unmet medical need. As we celebrate our 20th year of bringing innovative therapies to patients affected by rare disorders, we reflect on our unwavering commitment to our patients, our science and our employees. -

Spinraza® (Nusinersen)

UnitedHealthcare® Commercial Medical Benefit Drug Policy Spinraza® (Nusinersen) Policy Number: 2021D0059I Effective Date: July 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Community Plan Policy Coverage Rationale ....................................................................... 1 • Spinraza® (Nusinersen) Documentation Requirements ...................................................... 3 Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 3 Background.................................................................................... 4 Benefit Considerations .................................................................. 5 Clinical Evidence ........................................................................... 5 U.S. Food and Drug Administration ............................................. 8 References ..................................................................................... 9 Policy History/Revision Information ........................................... 10 Instructions for Use ..................................................................... 11 Coverage Rationale See Benefit Considerations Spinraza® (nusinersen) is proven and medically necessary for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in patients who meet all of the following criteria: 1-4,22,23 Initial Therapy Diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy by, or in consultation with, a neurologist with expertise in the diagnosis of SMA; and Submission of medical records (e.g., chart notes, laboratory values) -

DRUGS REQUIRING PRIOR AUTHORIZATION in the MEDICAL BENEFIT Page 1

Effective Date: 08/01/2021 DRUGS REQUIRING PRIOR AUTHORIZATION IN THE MEDICAL BENEFIT Page 1 Therapeutic Category Drug Class Trade Name Generic Name HCPCS Procedure Code HCPCS Procedure Code Description Anti-infectives Antiretrovirals, HIV CABENUVA cabotegravir-rilpivirine C9077 Injection, cabotegravir and rilpivirine, 2mg/3mg Antithrombotic Agents von Willebrand Factor-Directed Antibody CABLIVI caplacizumab-yhdp C9047 Injection, caplacizumab-yhdp, 1 mg Cardiology Antilipemic EVKEEZA evinacumab-dgnb C9079 Injection, evinacumab-dgnb, 5 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent BERINERT c1 esterase J0597 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), Berinert, 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent CINRYZE c1 esterase J0598 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), Cinryze, 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent FIRAZYR icatibant J1744 Injection, icatibant, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent HAEGARDA c1 esterase J0599 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), (Haegarda), 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent ICATIBANT (generic) icatibant J1744 Injection, icatibant, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent KALBITOR ecallantide J1290 Injection, ecallantide, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent RUCONEST c1 esterase J0596 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (recombinant), Ruconest, 10 units Injection, lanadelumab-flyo, 1 mg (code may be used for Medicare when drug administered under Cardiology Hemostatic Agent TAKHZYRO lanadelumab-flyo J0593 direct supervision of a physician, not for use when drug is self-administered) Cardiology Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension EPOPROSTENOL (generic) -

New Brunswick Drug Plans Formulary

New Brunswick Drug Plans Formulary August 2019 Administered by Medavie Blue Cross on Behalf of the Government of New Brunswick TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction.............................................................................................................................................I New Brunswick Drug Plans....................................................................................................................II Exclusions............................................................................................................................................IV Legend..................................................................................................................................................V Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification of Drugs A Alimentary Tract and Metabolism 1 B Blood and Blood Forming Organs 23 C Cardiovascular System 31 D Dermatologicals 81 G Genito Urinary System and Sex Hormones 89 H Systemic Hormonal Preparations excluding Sex Hormones 100 J Antiinfectives for Systemic Use 107 L Antineoplastic and Immunomodulating Agents 129 M Musculo-Skeletal System 147 N Nervous System 156 P Antiparasitic Products, Insecticides and Repellants 223 R Respiratory System 225 S Sensory Organs 234 V Various 240 Appendices I-A Abbreviations of Dosage forms.....................................................................A - 1 I-B Abbreviations of Routes................................................................................A - 4 I-C Abbreviations of Units...................................................................................A -

Circulating Biomarkers in Neuromuscular Disorders: What Is Known, What Is New

biomolecules Review Circulating Biomarkers in Neuromuscular Disorders: What Is Known, What Is New Andrea Barp 1,* , Amanda Ferrero 1, Silvia Casagrande 1,2 , Roberta Morini 1 and Riccardo Zuccarino 1 1 NeuroMuscular Omnicentre (NeMO) Trento, Villa Rosa Hospital, Via Spolverine 84, 38057 Pergine Valsugana, Italy; [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (R.Z.) 2 Department of Neurosciences, Drug and Child Health, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134 Florence, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The urgent need for new therapies for some devastating neuromuscular diseases (NMDs), such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has led to an intense search for new potential biomarkers. Biomarkers can be classified based on their clinical value into different categories: diagnostic biomarkers confirm the presence of a specific disease, prognostic biomarkers provide information about disease course, and therapeutic biomarkers are designed to predict or measure treatment response. Circulating biomarkers, as opposed to instrumental/invasive ones (e.g., muscle MRI or nerve ultrasound, muscle or nerve biopsy), are generally easier to access and less “time-consuming”. In addition to well-known creatine kinase, other promising molecules seem to be candidate biomarkers to improve the diagnosis, prognosis and prediction of therapeutic response, such as antibodies, neurofilaments, and microRNAs. However, there are some criticalities that can complicate their application: variability during the day, stability, and reliable performance metrics Citation: Barp, A.; Ferrero, A.; (e.g., accuracy, precision and reproducibility) across laboratories. In the present review, we discuss Casagrande, S.; Morini, R.; Zuccarino, the application of biochemical biomarkers (both validated and emerging) in the most common NMDs R. -

Corporate Medical Policy

Corporate Medical Policy Nusinersen (Spinraza™) File Name: nusinersen_spinraza Origination: 03/2017 Last CAP Review: 10/2020 Next CAP Review: 10/2021 Last Review: 10/2020 Description of Procedure or Service Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an inherited disorder caused by homozygous deletions or variants in the SMN1 gene. As a consequence of low levels of SMN1 protein, the motor neurons in spinal cord degenerate, resulting in atrophy of the voluntary muscles of the limbs and trunk. Nusinersen is a synthetic antisense oligonucleotide designed to bind to a specific sequence in exon 7 of the SMN2 transcript causing the inclusion of exon 7 in the SMN2 transcript, leading to production of full length functional SMN2 protein, which demonstrates similarity to SMN1. SPINAL MUSCULAR ATROPHY Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by homozygous deletions or variants in the SMN1 gene in chromosome 5. This gene is responsible for producing the “survival of motor neuron” protein (SMN1). As a consequence of absent or low levels of this protein, the motoneurons in the spinal cord degenerate, resulting in atrophy of the voluntary muscles of the limbs and trunk. During early development, these muscles are necessary for crawling, walking, sitting up, and head control. The more severe types of SMA can also affect muscles involved in feeding, swallowing, and breathing. The exact role of the SMN protein in motoneurons has not been completely elucidated and levels of the SMN protein required for optimal functioning are unknown. SMN2 is a nearly identical modifying gene capable of producing compensatory SMN protein. -

Outpatient Drug Services Handbook

Texas Medicaid Provider Procedures Manual December 2020 Provider Handbooks Outpatient Drug Services Handbook The Texas Medicaid & Healthcare Partnership (TMHP) is the claims administrator for Texas Medicaid under contract with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. TEXAS MEDICAID PROVIDER PROCEDURES MANUAL: VOL. 2 DECEMBER 2020 OUTPATIENT DRUG SERVICES HANDBOOK Table of Contents 1 General Information . 7 1.1 About the Vendor Drug Program. 7 1.2 Pharmacy Enrollment . 8 1.3 Program Contact Information. 8 2 Enrollment . 8 3 Services, Benefits, Limitations, and Prior Authorization. .8 3.1 Prior Authorization Requests . 9 3.2 Electronic Signatures in Prior Authorizations . 9 4 Reimbursement. .10 5 Injectable Medications as a Pharmacy Benefit. .11 6 National Drug Code (NDC) . .12 6.1 Calculating Billable HCPCS and NDC Units . .12 6.1.1 Single-Dose Vials Calculation Examples . 12 6.1.2 Multi-Dose Vials Calculation Examples . 13 6.1.3 Single and Multi-Use Vials . 13 6.1.4 Nonspecific, Unlisted, or Miscellaneous Procedure Codes . 14 7 Outpatient Drugs—Benefits and Limitations. .15 7.1 Abatacept (Orencia) . .15 7.1.1 Prior Authorization for Abatacept (Orencia) . 15 7.2 Adalimumab. .16 7.3 Ado-trastuzumab entansine (Kadcyla). .17 7.4 Alglucosidase Alfa (Myozyme) . .18 7.5 Amifostine . .18 7.6 Antibiotics and Steroids . .22 7.7 Antisense Oligonucleotides (eteplirsen, golodirsen, and nusinersen) . .22 7.7.1 Prior Authorization Requirements. 22 7.7.1.1 Initial Requests (for all Antisense Oligonucleotides) . 23 7.7.1.2 Recertification/Extension Requests (for all Antisense Oligonucleotides). 25 7.7.1.3 Exclusions . 25 7.8 Aripiprazole Lauroxil, (Aristada Initio). -

Zolgensma, INN-Onasemnogene Abeparvovec

26 March 2020 EMA/200482/2020 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) Assessment report Zolgensma International non-proprietary name: onasemnogene abeparvovec Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/004750/0000 Note The CAT Assessment report has been endorsed by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents 1. Background information on the procedure .............................................. 6 1.1. Submission of the dossier ...................................................................................... 6 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ......................................................... 9 2. Scientific discussion .............................................................................. 10 2.1. Problem statement ............................................................................................. 10 2.1.1. Disease or condition ......................................................................................... 10 2.1.2. Epidemiology .................................................................................................. 11 2.1.3. -

Virtual Posters

VIRTUAL POSTERS Poster # Title Primary Author First Name Primary Author Last Name City State Brain Tumors/OnCology 200 Clinical and Molecular Features of Atypical Pediatric Neurocytoma: A Case Series Adam Kalawi San Diego CA 201 Atypical molecular features of pediatric tectal glioma: A single institutional series Maayan Yakir San Diego CA 202 Hypercalcemia in Use of the Ketogenic Diet for Treatment of Spinal Lipoma Lila Worden Hartford CT Cognitive/Behavioral Disorders (inCluding Autism) 203 The neurodevelopmental profile of HIVEP2-related disorder Alisa Mo Boston MA 204 Burden of disease in a rare neurologic disorder: caregiver’s perspective on Aicardi Goutières Syndrome Francesco Gavazzi Philadelphia PA 205 Diagnosis delay in Aicardi Goutières Syndrome: a parents’ perspective Francesco Gavazzi Philadelphia PA 206 Validation of the telemedicine application of the Gross Motor Function Measure-88 Francesco Gavazzi Philadelphia PA 207 Altered Cerebellar White Matter in Sensory Processing Dysfunction Is Associated With Impaired Multisensory Integration and Attention Elysa Marco San Rafael CA 208 A comparison of the adaptive and autistic behavior in three developmental epileptic encephalopathies – SLC6A1, SCN2A, STXBP1 Kimberly Goodspeed Dallas TX 209 Spatial topography of cross-frequency coupling during NREM sleep is disrupted in Rett Syndrome Patrick Davis Boston MA 210 Serotonin transporter genotype predicts adaptive behavior outcomes in children with autism Kevin Shapiro Los Angeles CA 211 Clinical and Numerical presentation of Neurocognitive -

ENTRY WATCH 2016 Published by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board June 2018 Meds Entry Watch, 2016 Is Available in Electronic Format on the PMPRB Website

MEDS ENTRY WATCH 2016 Published by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board June 2018 Meds Entry Watch, 2016 is available in electronic format on the PMPRB website. Une traduction de ce document est également disponible en français sous le titre : Veille des médicaments mis en marché, 2016 Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Standard Life Centre Box L40 333 Laurier Avenue West Suite 1400 Ottawa, ON K1P 1C1 Tel.: 1-877-861-2350 TTY 613-288-9654 Email: [email protected] Web: www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca ISSN 2560-6204 Cat. No.: H79-12E-PDF © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the NPDUIS initiative of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, 2018 MEDS ENTRY WATCH 2016 About the PMPRB Acknowledgements The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board This report was prepared by the Patented (PMPRB) is a respected public agency that makes Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) a unique and valued contribution to sustainable as part of the National Prescription Drug spending on pharmaceuticals in Canada by: Utilization Information System (NPDUIS). ~ providing stakeholders with price, cost and The PMPRB would like to acknowledge the utilization information to help them make timely contributions of and knowledgeable drug pricing, purchasing and ~ The members of the NPDUIS Advisory reimbursement decisions; and Committee for their expert oversight and ~ acting as an effective check on the patent rights guidance in the preparation of this report. of pharmaceutical manufacturers through the ~ PMPRB NPDUIS staff for their contribution responsible and efficient use of its consumer to the analytical content of the report: protection powers. -

Aetna PA Info

Procedures, programs and drugs that require precertification Participating provider precertification list Starting June 1, 2021 Applies to the following plans (also see General information section #1-#4, #9-#10): Aetna® plans, except Traditional Choice® plans All health benefits and insurance plans offered and/or underwritten by Innovation Health plans, Inc., and Innovation Health Insurance Company, except indemnity plans, Foreign Service Benefit Plan, MHBP and Rural Carrier Benefit Plan All health benefits and health insurance plans offered, underwritten and/or administered by the following: Banner Health and Aetna Health Insurance Company and/or Banner Health and Aetna Health Plan Inc. (Banner|Aetna), Texas Health +Aetna Health Insurance Company and/or Texas Health+Aetna Health Plan Inc. (Texas Health Aetna), Allina Health and Aetna Health Insurance Company (Allina Health| Aetna), Sutter Health and Aetna Administrative Services LLC (Sutter Health | Aetna) Aetna.com 23.03.882.1 R (6/21) For more information, read all general precertification guidelines Providers may submit most precertification requests electronically through the secure provider website or using your Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system portal. (See #1 in the General Information section for more information on precertification.) Services that require precertification: 1. Inpatient confinements (except hospice) 18. Nonparticipating freestanding ambulatory For example, surgical and nonsurgical stays, surgical facility services, when referred by stays in a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation a participating provider facility, and maternity and newborn stays that 19. Orthognathic surgery procedures, bone exceed the standard length of stay (LOS). (See grafts, osteotomies and surgical #6 in the General Information section.) management of the temporomandibular 2. Ambulance joint Precertification required for transportation by 20.