Creativity & Religion: a Self-Study of Mormon Mindset in the Art Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Kirk Richards

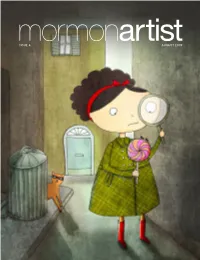

mormonartist Issue 1 September 2008 inthisissue Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray J. Kirk Richards Aaron Martin New Play Project editor.in.chief mormonartist Benjamin Crowder covering the Latter-day Saint arts world proofreaders Katherine Morris Bethany Deardeuff Mormon Artist is a bimonthly magazine Haley Hegstrom published online at mormonartist.net and in print through MagCloud.com. Copyright © 2008 Benjamin Crowder. want to help? All rights reserved. Send us an email saying what you’d be Front cover paper texture by bittbox interested in helping with and what at flickr.com/photos/31124107@N00. experience you have. Keep in mind that Mormon Artist is primarily a Photographs pages 4–9 courtesy labor of love at this point, so we don’t Margaret Blair Young and Darius Gray. (yet) have any money to pay those who help. We hope that’ll change Paintings on pages 12, 14, 17–19, and back cover reprinted soon, though. with permission from J. Kirk Richards. Back cover is “Pearl of Great Price.” Photographs on pages 2, 28, and 39 courtesy New Play Project. Photograph on pages 1 and 26 courtesy Vilo Elisabeth Photography, 2005. Photograph on page 34 courtesy Melissa Leilani Larson. Photograph on page 35 courtesy Gary Elmore. Photograph on page 37 courtesy Katherine Gee. contact us Web: mormonartist.net Email: [email protected] tableof contents Editor’s Note v essay Towards a Mormon Renaissance 1 by James Goldberg interviews Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray 3 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder J. Kirk Richards 11 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder Aaron Martin 21 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder New Play Project 27 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder editor’snote elcome to the pilot issue of what will hope- fully become a longstanding love affair with the Mormon arts world. -

A Study of the Effect of Color in the Utah Temple Murals

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Study of the Effect of Color in the Utah Temple Murals Terry John O'Brien Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation O'Brien, Terry John, "A Study of the Effect of Color in the Utah Temple Murals" (1968). Theses and Dissertations. 4990. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4990 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF COLOR INTHEIN THE UTAH TEMPLE MMALSMURALS 41k V A thesisthes is presented to the department of art brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for thedegreethe degree master of arts by terryjohnterry john obrien may 19196868 m TABLE OF CONTENTS page LIST OF TABLES e 0 9 0 0 0 0 0 19 0 0 0 vi chapter I1 introduction 0 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 statement of the problem questions and data inherent to the problem justificationustifaustif icationmication and signifsigniasignificance3 cance of the study sourcsourasourceses of information delimitations of thestathestuthe studydy organization oftheodtheof the material basic assumptions definition of terms II11 THE FOUR UTAH TEMPLES AND THEIR ARTISTS 0 0 11 temple beginnings -

Wise Or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 4 2018 Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Champoux, Jennifer (2018) "Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol57/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Champoux: Wise or Foolish Wise or Foolish Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux isual imagery is an inescapable element of religion. Even those Vgroups that generally avoid figural imagery, such as those in Juda- ism and Islam, have visual objects with religious significance.1 In fact, as David Morgan, professor of religious studies and art history at Duke University, has argued, it is often the religions that avoid figurative imag- ery that end up with the richest material culture.2 To some extent, this is true for Mormonism. Although Mormons believe art can beautify a space, visual art is not tied to actual ritual practice. Chapels, for exam- ple, where the sacrament ordinance is performed, are built with plain walls and simple lines and typically have no paintings or sculptures. Yet, outside chapels, Mormons enjoy a vast culture of art, which includes traditional visual arts, texts, music, finely constructed temples, clothing, historical sites, and even personal devotional objects. -

THESIS a REASON to BELIEVE: a RHETORICAL ANALYSIS of MORMON MISSIONARY FILMS Submitted by Sky L. Anderson Department of Communic

THESIS A REASON TO BELIEVE: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF MORMON MISSIONARY FILMS Submitted by Sky L. Anderson Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2012 Master’s Committee Advisor: Carl Burgchardt Eric Aoki Kathleen Kiefer ABSTRACT A REASON TO BELIEVE: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF MORMON MISSIONARY FILMS In this analysis, I examine Mormon cinema and how it functions on a rhetorical level. I specifically focus on missionary films, or movies that are framed by LDS missionary narratives. Through an analysis of two LDS missionary films, namely Richard Dutcher’s God’s Army (2000) and Mitch Davis’ The Other Side of Heaven (2001), I uncover two rhetorical approaches to fostering spirituality. In my first analysis, I argue that God’s Army presents two pathways to spirituality: one which produces positive consequences for the characters, and the other which produces negative consequences. I call these pathways, respectively, ascending and descending spirituality, and I explore the rhetorical implications of this framing. In my second analysis, I contend that The Other Side of Heaven creates a rhetorical space wherein the audience may transform. Specifically, the film constructs a “Zion,” or a heaven on earth, with three necessary components, which coincide perfectly with established LDS teachings: God, people, and place. These three elements invite the audience to accept that they are imperfect, yet they can improve if they so desire. Ultimately, by comparing my findings from both films, I argue that the films’ rhetorical strategies are well constructed to potentially reinforce beliefs for Mormon audiences, and they also may invite non-Mormons to think more positively about LDS teachings. -

Mormon Abstract

Abstract http://www.mormonartistsgroup.com/Mormon_Artists_Group/Abstract.html Welcome What's New Works Glimpses Events Freebies About MAG Contact Mormon Abstract by Stephanie K. Northrup January 2010 [i] When you think of Mormons “pushing the envelope,” what comes to mind? Deacons at the door collecting fast offerings? Try Bethanne Andersen’s The Last Supper (Place Setting). Many beautiful renditions of the Last Supper already exist, telling the story through dramatic lighting, facial expressions, and body language. Andersen tries a new perspective. She paints the dishes from which Christ eats His last mortal meal. That’s it. No people. Just us – invited to put ourselves in His shoes. The dishes are painted in soft pastel, as if on the verge of fading. This is a fleeting moment, like mortality, as He sits with His friends before making the ultimate sacrifice. By pushing the envelope, by throwing a new image at us that makes us consider the story in a new way, Andersen invites viewer participation. What a great approach to “likening the scriptures.” While Greg Olsen, Del Parson, and Simon Dewey are household names, ask most Mormons to name an abstract artist in the Church and you’ll probably get blank stares. Do Mormons make abstract art? We do. And we have been for a long time. In 1890, the church sent John Hafen and other “art missionaries” to Paris. Their assignment was to improve their skill so that they could create art for the Salt Lake Temple. What did these artists return with? Impressionism! Bright, thick brush strokes replaced traditional refined detail. -

The Cloning of Mormon Architecture

THE CLONING OF MORMON ARCHITECTURE MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY THOUGH BRIGHAM YOUNGS SERMONS were often full of exaggerations, he was right on the mark when he said, To accomplish this work there will have to be not only one temple but thousands of them, and thousands of ten thousands of men and women will go into those temples and officiate.1 Brigham clearly envisioned the 6,500 church buildings the Latter-day Saints would have erected by 1980. The architectural history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reflects an industrious, proud and diversified tradition in style, technology and objective. Mormon architecture, always responsive to the changing environment, has expressed changes in church membership, tastes, philosophy and the organizational structure of the Church itself. Historically, Latter-day Saints have had three distinct forms of ecclesiasti- cal architecture: the temple, the tabernacle and the ward meetinghouse. In the nineteenth century, these three types were clearly distinguishable in size, style and function. In the mid-twentieth century, however, when tab- ernacles were no longer built by the Church, temples and ward meeting- houses drew closer in style and character. Even in pioneer times, Mormon architecture expressed little that was truly indigenous. Most styles and forms, like the castellated Gothic style of the Salt Lake Temple, were adapted from other historical periods and applied to Mormon culture. The period beginning in 1920 became identified with a growing conservatism and historicity in architectural attitudes and practice, MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY is currently completing her master's thesis at BYU. She presented this paper at the Mosaic of Mormon Culture Sesquicentennial Symposium 1980 at BYU. -

Mormon Recruitment of Christian Young People

How Mormons Recruit Christian Young People for the LDS Church By the Mother of a Mormon who has a Heart for the Lost “Go, therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19). Most Christians will recognize the words above as the Great Commission where Jesus Christ commanded His disciples and followers (that’s us!) to share the good news of salvation with all people. Many Christians take these words very seriously. But, others do not. Some Christian who do not take the Great Commission seriously may not feel equipped to share their faith. Others may be afraid to share their faith. And still others may be babes in Christ. We should pray that the Lord would strengthen their faith and encourage them to grow spiritually. But the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter‐day Saints (LDS/Mormons) do take these words seriously. Mormons are knocking on doors, sharing their false teachings and beliefs, and convincing the uninformed Christian and those with no faith that they have the true church. In particular the Mormons are reaching out to your children and youth who may be Biblically uninformed. How do they reach out to your children, youth, and young adults? First, LDS children are trained starting at age 2 or 3 to give their testimony of their faith. They receive training in their faith at church, Sunday school, Family home night (Mondays), Boy Scouts or young Women Activities and camping, classes at Seminaries (high school) or Institutes (colleges). -

August 2004 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • AUGUST 2004 Love of Mother and Father, p. 8 Welcome to Relief Society, p. 14 Move More, Stress Less, p. 58 Seed of Faith, by Jay Ward Young mothers such as this one were among the Anti-Nephi-Lehies who, the scriptures say, believed the gospel and “never did fall away” (Alma 23:6). Their testimonies of Christ would lead their sons who fought with the 2,000 stripling warriors to say, “We do not doubt our mothers knew it” (Alma 56:48). AUGUST 2004 • VOLUME 34, NUMBER 8 2 FIRST PRESIDENCY MESSAGE Fathers, Mothers, Marriage President James E. Faust 8 GOSPEL CLASSICS Love of Mother and Father President Joseph F. Smith 11 Walking with Richard Eugene I. Freedman 14 Welcome to Relief Society LaRene Porter Gaunt 18 My Answer in a Hymn Rena N. Evers 20 BOOK OF MORMON PRINCIPLES Welcome to Be Strong and of a Good Courage 14 Relief Society Elder John R. Gibson 24 Worshiping at Sacrament Meeting Elder Russell M. Nelson 29 An Unexpected Healing Mary Whaley 32 Carry On! Carry On! Janet Peterson 38 Exceedingly Great Faith 42 Book of Mormon before Breakfast Betty Jan Murphy 44 Forgiveness: Our Challenge and Our Blessing Steve F. Gilliland An Unexpected 49 At Home with Missionary Work Healing Jane Forsgren 29 52 When Your Child Is Depressed Sean E. Brotherson 58 Move More, Stress Less! Larry A. Tucker 60 Knowing My Eternal Self Sheila Olsen 64 BOOK OF MORMON PRINCIPLES They Think They Are Wise Elder Richard D. -

The Improvement Era Welcomes Contributions but Is Not Responsible for Unsolicited Manuscripts

/ "^«»*• t% .**-i ^wss^ ^^i*' \n '-!#** .-•^- mL j%Ji 1^: 'Ml*'-' .mm^%-. ix i^' :!f^^te"--. ^^- W"«t On the Cover: This month we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the First Vision, which was experienced by the boy prophet, Joseph Smith, in the spring of 1820 in western New York. There, after gaining The Voice of the Church April 1970 Volume 73, Number 4 confidence in the declaration of James —"If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God"—the 14-year-old youth Special Features turned to prayer in his quest to know 2 Editor's Page: "For Thus Shall My Church Be Called," President Joseph "which of all the sects was right." The Fielding Smith beautiful painting reproduced on our 4 Eight Contemporary Accounts of Joseph Smith's First Vision: What Do front cover is used widely by the We Learn from Them? Dr. James B. Allen Church Information Service in visitors 16 The House Where the Church Was Organized, Dr. Richard Lloyd centers throughout the world. The Anderson Historian, M. artist is Ken Riley. 26 Elder Howard W. Hunter, Church Jay Todd Of special interest is the photograph 28 A Festival of Mormon Art H. Greenhaigh below of President Joseph F. Smith, 31 How Far Is Heaven? Sadie nephew of the Prophet and father of 38 I Knew Courage, Jean Hart 2: Marriage Dr. J. Joel President Joseph Fielding Smith, as he 64 A Happier Marriage, Part Enjoy Your Moments, Call visited the Sacred Grove in the early and Audra Moss 1900s. 68 The Message, Dwane J. -

Mormons and the Visual Arts.” Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol

James L. Haseltine, “Mormons and the Visual Arts.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 1 No. 2 (1966): 17–34. Copyright © 2012 Dialogue Foundation. All Rights Reserved • A JOURNAL OF dialogue• MORMON THOUGHT MORMONS AND THE VISUAL ARTS James L. Haseltine This essay is the third in a continuing series, "An Assessment of Mormon Culture." The author, himself not a Mormon, examines the influence of the L.D.S. Church on the visual arts in Utah from pioneer times. Mr. Haseltine is Director of the Salt Lake Art Center and the author of numerous reviews and articles for professional journals; he recently produced a retrospective exhibit of Utah painting at the Art Center and did much of the research used in this essay in preparing the exhibition catalogue, "100 Years of Utah Painting." It seems curious to ask, "What support has the C h u r c h of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints given to the v i s u a l arts in Utah?" One would hardly consider as fields for fruitful exploration Baptist sup- port of the a r t s in Mississippi, Lutheran encouragement in Oregon, or Methodist patronage in Kansas. Yet in Utah perhaps such a ques- tion can b e asked, for seldom has o n e religion been so intertwined with other aspects of life. There is little doubt that Brigham Young felt a need for artists in the Salt Lake Valley very soon after the arrival of t h e first pioneers. By the mid-1850's he was instructing missionaries in foreign lands to devote special attention to t h e conversion of s k i l l e d artists, artisans, and architects. -

ART and the CHURCH Maida Rust Withers

ART AND THE CHURCH Maida Rust Withers It is through the performance of creative arts, in art, in thought in personal relationships that the city can be identified as something more than a purely functional organization . —Lewis Mumford Perhaps it is presumptuous to discuss the relationship of the arts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Some would question that there need be a relationship, but due to the personal nature of religious experience and the personal nature of art, there is a natural relationship. Religious ex- perience involves the same senses as artistic experience and they both involve a level of communication that can exceed the verbal form. It might appear overdramatic to discuss the need for emotional experience in our religious services in this 20th century. I do not speak of emotional exper- ience in a therapeutic context. For example, weekly religious experience is directly related to the environment in which we worship. The depth of in- volvement and attitude is affected by the church setting. In Arlington, Vir- ginia, there is a simple and yet magnificent Unitarian church. As you sit in beautiful, austere space, you look up and out. The structure itself demands that you lift yourself up to the space in which you reside. You look into a beautiful wooded area with long thin straight trees. This church, architectur- ally, gives you a feeling of eternity and a feeling of oneness with the universe. It is a religious experience in itself merely to be in that place. 94/DIALOGUE: A Journal of Mormon Thought There has recently been a rebirth of interest in the arts by other religious groups. -

ISSUE 6 Artistaugust 2009 Editor-In-Chief Mormonartist Ben Crowder Covering the Latter-Day Saint Arts World Managing Editor Katherine Morris

mormonISSUE 6 artistAUGUST 2009 EDitOR-IN-CHieF mormonartist Ben Crowder COVERING THE LatteR-DAY saiNT ARts WORLD MANagiNG EDitOR Katherine Morris seCtiON EDitORS Mormon Artist is a quarterly magazine Literature: Katherine Morris published online at MORMONARtist.Net Visual Arts: Megan Welton Music & Dance: Meridith Jackman issn 1946-1232. Copyright © 2009 Mormon Artist. Film: Meagan Brady Theatre: Annie Mangelson All rights reserved. COPY EDitORS All reprinted pieces of artwork copyright their respective owners. Annie Mangelson Jennifer McDaniel Front cover artwork courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. Katherine Morris Back cover photograph courtesy Greg Deakins. Meagan Brady Megan Welton Paintings on pages vii, viii courtesy J. Kirk Richards. Meridith Jackman Photographs on pages 1–4, 6–9 courtesy Greg Deakins. Photographs on pages 10, 11, 15 courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. THis issue Artwork on pages 12–14 courtesy Cambria Evans Christensen. WRiteRS Amelia Chesley Photographs on pages 16, 18–21 courtesy Perla Antoniak. Amy Baugher David Layton Photographs on pages 22–24 courtesy Debra Fotheringham. Mahonri Stewart Menachem Wecker Photographs on pages 26, 27, 29 courtesy April Bladh. PHOTOGRAPHERS Greg Deakins “Catch” reprinted with permission from Patrick Madden. Want to help out? See: Design by Ben Crowder. http://mormonartist.net/volunteer CONtaCT us WEB MORMONARtist.Net EMaiL [email protected] taBLE OF CONteNts Editor’s Note iv Submission Guidelines v ARtiCLE Are Scholars and Museums vi Ignoring Mormon Artists? BY MENACHEM WECKER LiteRatuRE Patrick Madden 1 BY AMELia CHesLEY Catch 5 BY PatRICK MADDEN Rick Walton 6 BY DAVID LAYTON VisuaL & APPLieD ARts Cambria Evans Christensen 10 BY MAHONRI steWART Perla Antoniak 18 BY AMY BaugHER MusiC & DANCE Debra Fotheringham 24 BY DAVID LAYTON FILM & THeatRE Danor Gerald 28 BY MAHONRI steWART EDitOR’S NOte t’s hard to believe, but Mormon Artist is now one year old.