Reshaping Hypsipyle's Narrative in Statius' Thebaid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orpheus and Mousikê in Greek Tragedy

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2016 Orpheus and mousikê in Greek Tragedy Semenzato, Camille Abstract: Much as he is famous, Orpheus is only mentioned by name fourteen times in the Greek tragedies and tragic fragments that have survived the ravages of time. Furthermore he is never shown as a protagonist, but always evoked by a dramatic character as an example, a parallel, a peculiarity, or a fantasy. This legendary singer is mentioned every time, if not explicitly, at least implicitly, in conjunction with DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/tc-2016-0016 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-171919 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Semenzato, Camille (2016). Orpheus and mousikê in Greek Tragedy. Trends in Classics, 8(2):295-316. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/tc-2016-0016 TC 2016; 8(2): 295–316 Camille Semenzato* Orpheus and mousikê in Greek Tragedy DOI 10.1515/tc-2016-0016 Abstract: Much as he is famous, Orpheus is only mentioned by name fourteen times in the Greek tragedies and tragic fragments that have survived the ravages of time. Furthermore he is never shown as a protagonist, but always evoked by a dramatic character as an example, a parallel, a peculiarity, or a fantasy. This leg- endary singer is mentioned every time, if not explicitly, at least implicitly, in con- junction with μουσική, the ‘art of the Muses’, namely ‘music’ in its fullest sense. -

Elegy with Epic Consequences: Elegiac Themes in Statius' Thebaid

Elegy with Epic Consequences: Elegiac Themes in Statius’ Thebaid A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by Carina Moss B.A. Bucknell University April 2020 Committee Chairs: Lauren D. Ginsberg, Ph.D., Kathryn J. Gutzwiller, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation examines the role of elegy in the Thebaid by Statius, from allusion at the level of words or phrases to broad thematic resonance. It argues that Statius attributes elegiac language and themes to characters throughout the epic, especially women. Statius thus activates certain women in the epic as disruptors, emphasizing the ideological conflict between the genres of Latin love elegy and epic poetry. While previous scholarship has emphasized the importance of Statius’ epic predecessors, or the prominence of tragic allusion in the plot, my dissertation centers the role of elegy in this epic. First, I argue that Statius relies on allusion to the genre of elegy to signal the true divine agent of the civil war at Thebes: Vulcan. Vulcan’s erotic jealousy over Venus’ affair with Mars leads him to create the Necklace of Harmonia. Imbued with elegiac resonance, the necklace comes to Argia with corrupted elegiac imagery. Statius characterizes Argia within the dynamic of the elegiac relicta puella and uses this framework to explain Argia’s gift of the necklace to Eriphyle and her advocacy for Argos’ involvement in the war. By observing the full weight of the elegiac imagery in these scenes, I show that Argia mistakenly causes the death of Polynices and the devastation at Thebes as the result of Vulcan’s elegiac curse. -

Download Full Text

SYMBOLIC POETICS OF BALANCE AND SPIRIT. FOUR READINGS (AND A CODA) AROUND THE WORK OF AIXA PORTERO. First Reading. The Mythological. The encounter between Aixa Portero and the mythological figure, Hypsipyle, is curious, paradoxical even. Curious, while understanding the pre-existence and persistence of a series of myths that, in their multiple variants, embody common archetypes which persist in our collective subconscious and that, as Steiner acknowledges, always return to us through art, literature or dreamlike situations, to a common, poetic terrain: “A thousand times over, blinded, aged fathers will cross waste places leaning on young, talismanic daughters. Once, the child is called Antigone; another time, Cordelia. Identical storms thunder over their wretched heads. A thousand times over, two men will fight from dawn to duck or through the night by a narrow ford or bridge and, after the struggle, bestow names on one another: be these Jacob/Israel and the Angel, Roland and Oliver, Robin Hood and Little John”1. Only rarely will the artist consciously strive to discover a myth that encapsulates their expressive needs and wherein they encounter their own reflection; time and again, the very myth reveals itself before the artist, who in turn relives it, procuring an encounter that in appearance, seems fortuitous. Passionate about literature in general and poetry in particular – whose verses she treats not as a literary resource, but rather according to their capacity to establish themselves as a mechanism of evocative detonation, once isolated from their logical narrative sequence – the creator (re)discovered one of the best known poems, Sonatina, by Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío (1867-1916). -

Breaking Boundaries: Medea As the “Barbarian” in Ovid's

BREAKING BOUNDARIES: MEDEA AS THE “BARBARIAN” IN OVID’S HEROIDES VI AND XII Chun Liu Abstract: Medea is an intriguing figure in Greek mythology who has been portrayed in a variety of ways by ancient Greek and Roman authors. One dominating feature in all her stories is her identity as an outsider who enters the mainland Greece through her marriage to Jason. In the Heroides, the Roman poet Ovid depicts Medea in two of the single letters. Taking advantage of his audience’ familiarity with the mythical tradition and possible awareness of previous literary works, Ovid plays on the idea of Medea as an outsider: in Hypsipyle’s Letter VI, Medea is represented as a barbarian, while in Letter XII Medea mocks “Greek” values and practices. Through intertextual references to each other and to the prior literary tradition, Ovid is able to portray a complicated, self-reflective figure in these two letters, whose multiple potentials are brought out when confronted with a diversity of life experiences. In creating a figure who breaks all boundaries, Ovid the poet is also breaking the boundaries of texts and genres. Of the heroines of all 15 single letters in Ovid’s Heroides, Medea takes up a little more than the average for the letters as a whole. In addition to Heroides XII which is under her name, Hypsipyle, the heroine of Heroides VI, also dwells extensively on Medea who has just replaced her by the side of Jason. It is obvious that Ovid himself is fascinated by the figure of Medea, and he gives various representations of her in different works. -

Structural Analysis of Jason and Medeia: an Interlocking Pair—Sisyphus Embodied Samuel Glaser-Nolan

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2015 A (Post) Structural Analysis of Jason and Medeia: An Interlocking Pair—Sisyphus Embodied Samuel Glaser-Nolan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Glaser-Nolan, Samuel, "A (Post) Structural Analysis of Jason and Medeia: An Interlocking Pair—Sisyphus Embodied" (2015). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 412. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A (Post) Structural Analysis of Jason and Medeia: An Interlocking Pair—Sisyphus Embodied Senior Thesis in Greek and Roman Studies Vassar College, Spring 2015 By Samuel Glaser-Nolan 1 “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” -Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus Introduction This project is concerned with the study of the myth of Jason and Medeia. Its specific aim is to analyze the myths of both protagonists in unison, as an interlocking pair, each component essential to understanding the other. Reading Jason and Medeia together reveals that they are characters perpetually struggling with the balance between the obligations of family and those of being a hero. They are structurally engaged with the tension between these two notions and can best be understood by allusion to other myths that provide precedents and parallels for their actions. The goal is to not only study both characters together but to do so across many accounts of the myth and view the myth in its totality, further unifying the separate analyses of the two characters. -

Dealing with a Massacre

DEALING WITH A MASSACRE Spectacle, Eroticism, and Unreliable Narration in the Lemnian Episode of Statius’ Thebaid by KYLE G. GERVAIS A thesis submitted to the Department of Classics in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada June, 2008 Copyright © Kyle G. Gervais, 2008 ABSTRACT I offer three readings of the Lemnian episode narrated by Hypsipyle in book five of the Thebaid, each based upon an interpretive tension created by textual, intertextual, and cultural factors and resolved by the death of Opheltes, the child nursed by Hypsipyle. In the first reading (chapter two), I suggest that Hypsipyle emphasizes the questionable nature of the evidence for the involvement of Venus and other divinities in the Lemnian massacre, which is on the surface quite obvious, as a subconscious strategy to deal with her fear of divine retribution against her and Opheltes. In the second reading (chapter three), I argue that much of the violence of the massacre is eroticized, primarily by allusions to Augustan elegy and Ovidian poetry, and that this eroticism challenges a straightforward, horrified reaction to the Lemnian episode. In the third reading (chapter four), which continues the argument of the second, I suggest that the reaction of Statius’ audience to the Lemnian massacre was influenced by familiarity with the violent entertainment offered in the Roman arena, and that this encouraged the audience to identify with the perpetrators of the massacre rather than the victims. The problematization of the audience’s reaction and of the divine involvement in the massacre is resolved by the death of Opheltes, which is portrayed as both undeniably supernatural in origin and emphatically tragic in nature. -

Thebaid' 1.1-45

A COMMENTARY ON STATIUS' 'THEBAID' 1.1-45 James Manasseh A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2017 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11354 This item is protected by original copyright A Commentary on Statius’ Thebaid 1.1-45 James Manasseh This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of MPhil at the University of St Andrews Date of Submission 22/11/16 ABSTRACT This dissertation discusses the proem of Statius’ Thebaid (1.1-45) and the analysis of the text is split between an introduction, three extended chapters and a lemmatized commentary. Statius’ acknowledgements of his literary debts, in particular Virgil, encourages, if not demands, an intertextual reading of his poetry. As such, my first chapter, Literary Models, looks at how Statius engages with his epic models, namely Homer, Virgil, Lucan and Ovid, but also how he draws upon the rich literary Theban tradition. Like all Roman poets, Statius is highly self-conscious of his craft, and draws upon Hellenistic and lyric models to enrich his epic and define himself as an exemplary poet. I will argue that the proem offers a useful lens for analysing the Thebaid and introduces his epic in exemplary fashion, in the sense that he draws attention to the concept of opening his epic with the use of traditional tropes (namely, the invocation of inspiring force; a recusatio; an imperial encomium and a synopsis of the poem’s narrative). -

Dictynna, 12 | 2015 Statius’ Nemea / Paradise Lost 2

Dictynna Revue de poétique latine 12 | 2015 Varia Statius’ Nemea / paradise lost Jörn Soerink Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1125 DOI: 10.4000/dictynna.1125 ISSN: 1765-3142 Electronic reference Jörn Soerink, « Statius’ Nemea / paradise lost », Dictynna [Online], 12 | 2015, Online since 27 January 2016, connection on 11 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1125 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/dictynna.1125 This text was automatically generated on 11 September 2020. Les contenus des la revue Dictynna sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Statius’ Nemea / paradise lost 1 Statius’ Nemea / paradise lost Jörn Soerink Introduction 1 In the fourth book of Statius’ Thebaid, the expedition of the Seven against Thebes is stranded in Nemea. Tormented by thirst – Bacchus has caused a drought in Nemea in order to delay the expedition against his favourite city – the Argives encounter Hypsipyle nursing Opheltes, son of Lycurgus and Eurydice, king and queen of Nemea. In order to guide the soldiers as fast as possible to the one remaining spring, Langia, Hypsipyle places her nurseling on the ground. When the Argives have quenched their thirst, Hypsipyle (re)tells them the story of the Lemnian massacre, which takes up most of the following book (5.49-498). In their absence, the infant Opheltes is accidentally killed by a monstrous serpent sacred to Jupiter (5.534-40). 2 The death of Opheltes nearly plunges Nemea into war. When Opheltes’ father Lycurgus hears of his son’s death (5.638-49), he wants to punish Hypsipyle for her negligence and attempts to kill her, but the Argive heroes defend their benefactress ; without the intervention of Adrastus and the seer Amphiaraus, this violent confrontation between the Argives and their Nemean allies doubtless would have ended in bloodshed (5.650-90). -

Reading Hypsipyle's Medea: Looking at the Chronology of Ovid's

Reading Hypsipyle’s Medea: Looking at the Chronology of Ovid’s Heroides 6 and 12 Until recently, scholars have viewed Ovid’s Heroides as a collection of letters that, though residing within a single collection, should be read individually, with little regard to other letters in the collection. As a result of this view, scholars have regarded the letters as, “little differentiated” (Wilkinson, 1962) and “monotonous” (Otis, 1970). More recent scholars, such as Laurel Fulkerson and Sara Lindheim, have looked at the similarities between each letter, not as “monotonous,” but instead as a way to unify the letters through the shared experiences of each heroine. Fulkerson (2005) in her introduction suggests that each letter should be read “centrally in the corpus,” suggesting that each heroine is influenced by other heroines within the Heroides, though not necessarily in any particular order. Building on Fulkerson’s idea, I suggest that, while a chronological reading of the most of the letters is unnecessary, one must read letter 6 (Hypsipyle to Jason) and letter 12 (Medea to Jason) in chronological order. This paper will analyze Medea’s letter to Jason, specifically the way in which Ovid situates Medea both in relation to the “source text” of Euripides’ Medea and within the Heroides, particularly in relation to letter 6. By analyzing Medea’s position in relation to both of these works, this paper will demonstrate that Ovid has fashioned Medea in such a way as to maximize her sympathy to the reader, both by omitting well-known episodes from her story and by surrounding her with heroines who share a similar fate. -

An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Textbooks Open Texts 2017 Mythology Unbound: An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology Jessica Mellenthin Utah State University Susan O. Shapiro Utah State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/oer_textbooks Recommended Citation Mellenthin, Jessica and Shapiro, Susan O., "Mythology Unbound: An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology" (2017). Textbooks. 5. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/oer_textbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Texts at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textbooks by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythology Unbound: An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology JESSICA MELLENTHIN AND SUSAN O. SHAPIRO Mythology Unbound by Susan Shapiro is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 Contents Map vii Aegis 1 Agamemnon and Iphigenia 5 Aphrodite 9 Apollo 15 Ares 25 The Argonauts 31 Artemis 41 Athena 49 Caduceus 61 Centaurs 63 Chthonian Deities 65 The Delphic Oracle 67 Demeter 77 Dionysus/Bacchus 85 Hades 97 Hephaestus 101 Hera 105 Heracles 111 Hermes 121 Hestia 133 Historical Myths 135 The Iliad - An Introduction 137 Jason 151 Miasma 155 The Minotaur 157 The Odyssey - An Introduction 159 The Oresteia - An Introduction 169 Origins 173 Orpheus 183 Persephone 187 Perseus 193 Poseidon 205 Prometheus 213 Psychological Myths 217 Sphinx 219 Story Pattern of the Greek Hero 225 Theseus 227 The Three Types of Myth 239 The Twelve Labors of Heracles 243 What is a myth? 257 Why are there so many versions of Greek 259 myths? Xenia 261 Zeus 263 Image Attributions 275 Map viii MAP Aegis The aegis was a goat skin (the name comes from the word for goat, αἴξ/aix) that was fringed with snakes and often had the head of Medusa fixed to it. -

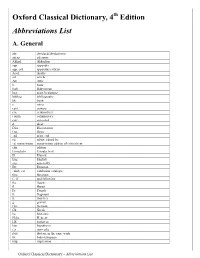

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Echoing Hylas : Metapoetics in Hellenistic and Roman Poetry Heerink, M.A.J

Echoing Hylas : metapoetics in Hellenistic and Roman poetry Heerink, M.A.J. Citation Heerink, M. A. J. (2010, December 2). Echoing Hylas : metapoetics in Hellenistic and Roman poetry. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16194 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16194 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). ECHOING HYLAS METAPOETICS IN HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN POETRY PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE UNIVERSITEIT LEIDEN , OP GEZAG VAN RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF .MR . P.F. VAN DER HEIJDEN , VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VOOR PROMOTIES TE VERDEDIGEN OP DONDERDAG 2 DECEMBER 2010 KLOKKE 15.00 UUR DOOR MARK ANTONIUS JOHANNES HEERINK GEBOREN TE OLDENZAAL IN 1978 Promotiecommissie promotor Prof.dr. J. Booth leden Prof.dr. M.A. Harder (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) Prof.dr. P.R. Hardie (Trinity College, Cambridge) Prof.dr. R.R. Nauta (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) Cover illustration: detail from J.W. Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs , 1896 (Manchester City Art Gallery). CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations ix INTRODUCTION : THE ECHO OF HYLAS 1. The myth of Hylas 1 2. The wandering echo 3 3. A metapoetical interpretation of the Hylas myth 7 4. Metapoetics in Hellenistic and Roman poetry 9 1. EPIC HYLAS : APOLLONIUS ’ ARGONAUTICA 1. Introduction 15 2. Jason vs. Heracles 16 2.1. Jason the love-hero 16 2.2. Too heavy for the Argo: Heracles in Argonautica 1 17 2.3. Jason: the best of the Argonauts 24 2.4.