4 a Regular Guy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

The Potential for Presidential Leadership

THE WHITE HOUSE TRANSITION PROJECT 1997-2021 Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power Report 2021—08 THE POTENTIAL FOR PRESIDENTIAL LEADERSHIP George C. Edwards III, Texas A&M University White House Transition Project Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power WHO WE ARE & WHAT WE DO The White House Transition Project. Begun in 1998, the White House Transition Project provides information about individual offices for staff coming into the White House to help streamline the process of transition from one administration to the next. A nonpartisan, nonprofit group, the WHTP brings together political science scholars who study the presidency and White House operations to write analytical pieces on relevant topics about presidential transitions, presidential appointments, and crisis management. Since its creation, it has participated in the 2001, 2005, 2009, 2013, 2017, and now the 2021. WHTP coordinates with government agencies and other non-profit groups, e.g., the US National Archives or the Partnership for Public Service. It also consults with foreign governments and organizations interested in improving governmental transitions, worldwide. See the project at http://whitehousetransitionproject.org The White House Transition Project produces a number of materials, including: . WHITE HOUSE OFFICE ESSAYS: Based on interviews with key personnel who have borne these unique responsibilities, including former White House Chiefs of Staff; Staff Secretaries; Counsels; Press Secretaries, etc. , WHTP produces briefing books for each of the critical White House offices. These briefs compile the best practices suggested by those who have carried out the duties of these office. With the permission of the interviewees, interviews are available on the National Archives website page dedicated to this project: . -

Henry Wallace Wallace Served Served on On

Papers of HENRY A. WALLACE 1 941-1 945 Accession Numbers: 51~145, 76-23, 77-20 The papers were left at the Commerce Department by Wallace, accessioned by the National Archives and transferred to the Library. This material is ·subject to copyright restrictions under Title 17 of the U.S. Code. Quantity: 41 feet (approximately 82,000 pages) Restrictions : The papers contain material restricted in accordance with Executive Order 12065, and material which _could be used to harass, em barrass or injure living persons has been closed. Related Materials: Papers of Paul Appleby Papers of Mordecai Ezekiel Papers of Gardner Jackson President's Official File President's Personal File President's Secretary's File Papers of Rexford G. Tugwell Henry A. Wallace Papers in the Library of Congress (mi crofi 1m) Henry A. Wallace Papers in University of Iowa (microfilm) '' Copies of the Papers of Henry A. Wallace found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, the Library of Congress and the University of Iow~ are available on microfilm. An index to the Papers has been published. Pl ease consult the archivist on duty for additional information. I THE UNIVERSITY OF lOWA LIBRAlU ES ' - - ' .·r. .- . -- ........... """"' ': ;. "'l ' i . ,' .l . .·.· :; The Henry A. Wallace Papers :and Related Materials .- - --- · --. ~ '· . -- -- .... - - ·- - ·-- -------- - - Henry A. Walla.ce Papers The principal collection of the papers of (1836-1916), first editor of Wallaces' Farmer; Henry Agard \Vallace is located in the Special his father, H enry Cantwell Wallace ( 1866- Collc:ctions Department of The University of 1924), second editor of the family periodical and Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. \ Val bee was born Secretary of Agriculture ( 1921-192-l:): and his October 7, 1888, on a farm in Adair County, uncle, Daniel Alden Wallace ( 1878-1934), editor Iowa, was graduated from Iowa State University, of- The Farmer, St. -

Leaders/Scholars Association

Selected Proceedings 1998 Annual Meeting: Leaders/Scholars Association Meeting of the Minds— between those who study leadership and those who practice it The James MacGregor Burns Center for the Advanced Study of Leadership of Study Advanced the for Center ACADEMY OF LEADERSHIP The James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership is committed to strengthening leadership of, by, and for the people.The Academy fosters responsible and ethical leadership through scholarship, education, and training in the public interest. The Center for the Advanced Study of Leadership is located in the James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership.The Center is dedicated to increasing the quantity and quality of scholarship in the field of Leadership Studies. It provides leadership scholars and reflective practitioners with a unique community, one that fosters intellectual discourse and mutual support among women and men from diverse backgrounds, disciplines, and areas of the world. For additional copies of this report, or for other publications from the Burns Academy, contact: The James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-7715 301/405-6100, voice 301/405-6402, fax [email protected] http://academy.umd.edu *The Center for the Advanced Study of Leadership thanks the W.K.Kellogg Foundation for its generous support. Cover photo: James MacGregor Burns (left), Senior Scholar at the James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership, and Warren Bennis, Founding Chairman of the Leadership Institute at the University of Southern California, at the Center for the Advanced Study of Leadership’s November 1998 conference in Los Angeles, California. Selected Proceedings 1998 Annual Meeting: Leaders/Scholars Association Meeting of the Minds— between those who study leadership and those who practice it Center for the Advanced Study of Leadership THE JAMES MACGREGOR BURNS ACADEMY OF LEADERSHIP Copyright © 1999 Copyright © 1999 by the James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership. -

Farm Security Administation Photographs in Indiana

FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION PHOTOGRAPHS IN INDIANA A STUDY GUIDE Roy Stryker Told the FSA Photographers “Show the city people what it is like to live on the farm.” TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress 1 Great Depression and Farms 1 Roosevelt and Rural America 2 Creation of the Resettlement Administration 3 Creation of the Farm Security Administration 3 Organization of the FSA 5 Historical Section of the FSA 5 Criticisms of the FSA 8 The Indiana FSA Photographers 10 The Indiana FSA Photographs 13 City and Town 14 Erosion of the Land 16 River Floods 16 Tenant Farmers 18 Wartime Stories 19 New Deal Communities 19 Photographing Indiana Communities 22 Decatur Homesteads 23 Wabash Farms 23 Deshee Farms 24 Ideal of Agrarian Life 26 Faces and Character 27 Women, Work and the Hearth 28 Houses and Farm Buildings 29 Leisure and Relaxation Activities 30 Afro-Americans 30 The Changing Face of Rural America 31 Introduction This study guide is meant to provide an overall history of the Farm Security Administration and its photographic project in Indiana. It also provides background information, which can be used by students as they carry out the curriculum activities. Along with the curriculum resources, the study guide provides a basis for studying the history of the photos taken in Indiana by the FSA photographers. The FSA - OWI Photographic Collection at the Library of Congress The photographs of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) - Office of War Information (OWI) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress form a large-scale photographic record of American life between 1935 and 1944. -

A Planners' Planner: John Friedmann's Quest for a General

A Planners’ Planner: John Friedmann’s Quest for a General Theory of Planning The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Sanyal, Bish. "A Planners’ Planner: John Friedmann’s Quest for a General Theory of Planning." Journal of the American Planning Association 84, 2 (April 2018): 179-191 As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1427616 Publisher Informa UK Limited Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124150 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Bish Sanyal A Planners’ Planner (2018) A Planners Planner: John Friedmann s Quest for a General Theory of Planning (2018). Journal of the American Planning Association, 84(2), 179-191. doi:10.1080/01944363.2018.1427616 A Planners’ Planner: John Friedmann’s quest for a general theory of planning Bish Sanyal Massachusetts Institute of Technology This paper honors the memory of Professor John Friedmann by reflecting on his professional contributions in two ways. First, the paper provides an overview of Friedmann’s career as a planner and planning academic, which spanned six decades and three continents, and highlights how a confluence of factors led to a paradigm shift in his thinking regarding the role of planning in social transformation. Second, the paper assesses Friedmann’s position on three issues of importance for practitioners—namely, problem formulation, the role of technical knowledge, and organizational learning. The paper concludes that the establishment of UCLA’s planning program is a testament to Friedmann’s critical view of planning practice, which posed fundamental challenges to conventional thinking. -

Profiles in Statesmanship: Seeking a Better World Bruce W. Jentleson

1 Profiles in Statesmanship: Seeking a Better World Bruce W. Jentleson Paper presented at the University of Virginia, International Relations Speaker Series April 12, 2013 Comments welcome; [email protected] Do not cite without permission 2 The usual metric for the world leaders’ scorecard is who has done the most to advance their own country’s national interests. The book I’m writing, Profiles in Statesmanship: Seeking a Better World, poses a different question: who has done the most to try to build peace, security and justice inclusive of, but not exclusive to, their own country’s particular national interests? There is statesmanship to make one’s own nation more successful. And there is Statesmanship to make the world a better place. This is not altruism, but it also is not just a matter of global interests as extensions of national ones as typically conceived. Both statesmanship and Statesmanship take tremendous skill and savvy strategy. The latter also takes a guiding vision beyond the way the world is to how it can and should be, as well as enormous courage entailing as it does great political and personal risk. Not surprisingly there are not a lot of nominees. Writing in 1910 and working with similar criteria --- not just “winning a brief popular fame . but to serving the great interests of modern states and, indeed, of universal humanity” --- the historian Andrew Dickson White identified Seven Great Statesmen.1 Two 19th century British historians compiled the four- volume Eminent Foreign Statesmen series, but using more the traditional small s-statesmanship criteria of just national interest. -

American Political Science Review

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000060 . POLITICAL SCIENCE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 08 Oct 2021 at 13:45:36 , on May 2018, Volume 112, Issue 2 112, Volume May 2018, University of Athens . May 2018 Volume 112, Issue 2 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-2.indd 1 21/03/18 7:36 AM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark D. -

1987 Spring – Bogue – “The History of the American Political Party System”

UN I VERS I TY OF WI SCONSIN Department of History (Sem. II - 1986-87) History 901 (The History of the American Political Party System) Mr. Bogue I APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTIES Robert R. Alford, "Class Voting in the Anglo-American Political Systems," in Seymour M. Lipsett and Stein Rokkan, PARTY SYSTEMS AND VOTER ALIGNMENTS: AN APPROACH TO COMPARATIVE POLITICS, 67-93. Gabriel W. Almond, et al., CRISIS, CHOICE AND CHANGE: HISTORICAL STUDIES OF POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT. *Richard F. Bensel, SECTIONALISM AND AMERICAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, 1880-1980. Lee Benson, et al., "Toward a Theory of Stability and Change in American Voting Patterns, New York State, 1792-1970," in Joel Silbey, et al, THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR, 78-105. Lee Benson, "Research Problems in American Political Historiography," in Mirra Komarovsky, COMMON FRONTIERS OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES, 113-83. Bernard L. Berelson, et al., VOTING: A STUDY OF OPINION FORMATION IN A PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN. Allan G. Bogue et al., "Members of the House of Representatives and the Processes of Modernization, 1789-1960," JOURNAL OF AMERICAN HISTORY, LXIII, (September 1976), 275-302. Cyril E. Black, THE DYNAMICS OF MODERNIZATION Paul F. Bourke and Donald A. DeBats, "Individuals and Aggregates: A Note on Historical Data and Assumptions," SOCIAL SCIENCE HISTORY (Spring 1980), 229-50. Paul F. Bourke and Donald A. DeBats, "Identifiable Voting in Nineteenth Century America, Toward a Comparison of Britain and the United States Before the Secret Ballot," PERSPECTIVES IN AMERICAN HISTORY, XI(l977-78), 259-288. David Brady, "A Reevaluation of Realignments in American Politics," American Political Science Review 79(March 1985), 28-49. -

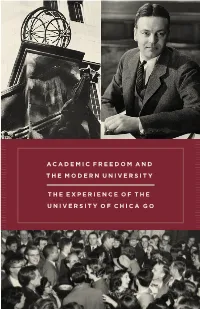

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W.