Policing Issues in Garrison Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAZILIAN Military Culture

BRAZILIAN Military Culture 2018 Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy | Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center By Luis Bitencourt The FIU-USSOUTHCOM Academic Partnership Military Culture Series Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy (FIU-JGI) and FIU’s Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (FIU-LACC), in collaboration with the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), formed the FIU-SOUTHCOM Academic Partnership. The partnership entails FIU providing research-based knowledge to further USSOUTHCOM’s understanding of the political, strategic, and cultural dimensions that shape military behavior in Latin America and the Caribbean. This goal is accomplished by employing a military culture approach. This initial phase of military culture consisted of a yearlong research program that focused on developing a standard analytical framework to identify and assess the military culture of three countries. FIU facilitated professional presentations of two countries (Cuba and Venezuela) and conducted field research for one country (Honduras). The overarching purpose of the project is two-fold: to generate a rich and dynamic base of knowledge pertaining to political, social, and strategic factors that influence military behavior; and to contribute to USSOUTHCOM’s Socio-Cultural Analysis (SCD) Program. Utilizing the notion of military culture, USSOUTHCOM has commissioned FIU-JGI to conduct country-studies in order to explain how Latin American militaries will behave in the context -

Amnesty International

amnesty international BRAZIL Extrajudicial execution of prisoner in Corumbá July 1993 AI Index: AMR 19/16/93 Distr: SC/CO/GR INTERNATIONAL SECRETARIAT, 1 EASTON STREET, LONDON WC1X 8DJ, UNITED KINGDOM £BRAZIL @Extrajudicial execution of prisoner in Corumbá Amnesty International is concerned at reports that indicate that Reinaldo Silva, a Paraguayan citizen, was extrajudicially executed on 20 March 1993, by members of the military police while in custody at the Hospital de Caridade, Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. According to the information received by Amnesty International, Reinaldo Silva, age 18, was being sought by the police accused of killing an off-duty police officer, on 19 March, in Corumbá, during a failed attempt at assaulting a taxi driver. During the exchange of fire with the off-duty police officer Reinaldo Silva was wounded in the cheek. The following day he gave himself up to the police under the protection of the Paraguayan consul in Corumbá, to whom the authorities had given assurances for Reinaldo Silva's physical safety. Reinaldo Silva was taken under police custody to the local hospital, Hospital de Caridade, to be treated for his wound. While he was undergoing treatment, the hospital was reportedly invaded by over 40 uniformed military police officers, who stormed the hospital's emergency treatment room and, overcoming the resistance of the hospital staff and the police guard, shot Reinaldo Silva dead. After killing Reinaldo Silva the police officers reportedly celebrated in the street by firing their weapons to the air. After the killing, the general command of the Mato Grosso do Sul military police ordered the removal of the commander of the Corumbá military police force from his post and the detention of the police officers involved in the assassination. -

NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book

NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book 2020 Amendments On January 4, 2020, the NRA Board of Directors approved the Law Enforcement Assistance Committees request to amend the NRA Police Pistol Combat Rule Book. These amendments have been incorporated into this web based printable PPC Rule Book. The 2020 amendments are as follows: Amendment 1 is in response to competitor requests concerning team matches at the National Police Shooting Championships. Current rules require that team match membership be comprised of members from the same law enforcement agency. A large percentage of competitors who attend the Championships are solo shooters, meaning they are the only member of their agency in attendance. The amendment allows the Championships to offer a stand-alone NPSC State Team Match so that solo competitors from the same state can compete as a team. The Match will be fired at the same time as regular team matches so no additional range time is needed, and State Team scores will only be used to determine placement in the State Team Match. NPSC State Team Match scores will not be used in determining National Team Champions, however they are eligible for National Records for NPSC State Team Matches. The amendment allows solo shooters the opportunity to fire additional sanctioned matches at the Championships and enhance team participation. 2.9 National Police Shooting Championships State Team Matches: The Tournament Director of the National Police Shooting Championships may offer two officer Open Class and Duty Gun Division NPSC Team Matches where team membership is comprised of competitors from the same state. For a team to be considered a NPSC State Team; 1. -

NATO ARMIES and THEIR TRADITIONS the Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION

NATO ARMIES AND THEIR TRADITIONS The Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION The Ancient Corps of the Royal Carabinieri was instituted in Turin by the King of Sardinia, Vittorio Emanuele 1st by Royal Warranty on 13th of July 1814. The Carabinieri Force was Issued with a distinctive uniform in dark blue with silver braid around the collar and cuffs, edges trimmed in scarlet and epaulets in silver, with white fringes for the mounted division and light blue for infantry. The characteristic hat with two points was popularly known as the “Lucerna”. A version of this uniform is still used today for important ceremonies. Since its foundation Carabinieri had both Military and Police functions. In addition they were the King Guards in charge for security and honour escorts, in 1868 this task has been given to a selected Regiment of Carabinieri (height not less than 1.92 mt.) called Corazzieri and since 1946 this task is performed in favour of the President of the Italian Republic. The Carabinieri Force took part to all Italian Military history events starting from the three independence wars (1848) passing through the Crimean and Eritrean Campaigns up to the First and Second World Wars, between these was also involved in the East African military Operation and many other Military Operations. During many of these military operations and other recorded episodes and bravery acts, several honour medals were awarded to the flag. The participation in Military Operations abroad (some of them other than war) began with the first Carabinieri Deployment to Crimea and to the Red Sea and continued with the presence of the Force in Crete, Macedonia, Greece, Anatolia, Albania, Palestine, these operations, where the basis leading to the acquirement of an international dimension of the Force and in some of them Carabinieri supported the built up of the local Police Forces. -

Mental Health and Physical Activity Level in Military Police Officers from Sergipe, Brazil

Motricidade © Edições Sílabas Didáticas 2020, vol. 16, n. S1, pp. 136-143 http://dx.doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.22334 Mental Health and Physical Activity Level in Military Police Officers from Sergipe, Brazil Victor Matheus Santos do Nascimento 1*, Levy Anthony Souza de Oliveira1, Luan Lopes Teles1, Davi Pereira Monte Oliveira1, Nara Michelle Moura Soares1 , Roberto Jerônimo dos Santos Silva1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE ABSTRACT The objective of the present study was to analyse the association between the level of physical activity and mental health indicators in this population. A total of 254 military police officers, male and female, aged between 21 and 55, participated in military battleships and police companies in the metropolitan region of Aracaju, Sergipe. They responded to an assessment form, available online, on Google Forms, containing questions about socio-demographic, anthropometric and occupational characteristics, quality of sleep (Pittsburgh scale), stress (EPS-10), anxiety and depression (HAD scale), Exhaustion syndrome (MBI - GS), suicidal ideation (YRBSS - adapted), and Physical Activity level (IPAQ-short). Officers classified as "insufficiently active" had a higher risk for "burnout syndrome" (OR = 2.49; CI: 95% 1.42-4.43) and a greater feeling of "deep sadness" (OR = 1.85; CI: 95% 1.03-3.33) compared with physically active colleagues. In addition, longer service time was a protective factor against anxiety (OR = 0.30; CI: 95% 0.13-0.68), burnout syndrome (OR = 0.28; CI: 95% 0.12 -0.67) and deep sadness (OR = 0.25; CI: 95% 0.11-0.57). Older officers are more likely to be affected by "deep sadness" (OR = 2.80; CI: 95% 1.37-5.71). -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew Its Government

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew its Government Samuel Gaspar Rodrigues Senior Honors History Thesis Professor Temma Kaplan April 20, 2012 Rodrigues 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................................................3 Before the War .....................................................................................................................9 The War .............................................................................................................................19 The April Captains .............................................................................................................33 Remembering the Past .......................................................................................................44 The Legacy of Colonial Portugal .......................................................................................53 Bibliography ......................................................................................................................60 Rodrigues 3 Introduction When the Portuguese people elected António Oliveira de Salazar to the office of Prime Minister in 1932, they believed they were electing the right man for the job. He appealed to the masses. He was a far-right conservative Christian, but he was less radical than the Portuguese Fascist Party of the time. His campaign speeches appeased the syndicalists as well as the wealthy landowners in Portugal. However, he never was -

CADETS in PORTUGUESE MILITARY ACADEMIES a Sociological Portrait

CADETS IN PORTUGUESE MILITARY ACADEMIES A sociological portrait Helena Carreiras Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte), Lisboa, Portugal Fernando Bessa Military University Institute, Centre for Research in Security and Defence (CISD), Lisboa, Portugal Patrícia Ávila Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte), Lisboa, Portugal Luís Malheiro Military University Institute, Centre for Research in Security and Defence (CISD), Lisboa, Portugal Abstract The aim of this article is to revisit the question of the social origins of the armed forces officer corps, using data drawn from a survey to all cadets following military training at the three Portuguese service academies in 2016. It puts forward the question of whether the sociological characteristics of the future military elite reveal a pattern of convergence with society or depart from it, in terms of geographical origins, gender and social origins. The article offers a sociological portrait of the cadets and compares it with previous studies, identifying trends of change and continuity. The results show that there is a diversified and convergent recruitment pattern: cadets are coming from a greater variety of regions in the country than in the past; there is a still an asymmetric but improving gender balance; self-recruitment patterns are rather stable, and there is a segmented social origin pointing to the dominance of the more qualified and affluent social classes. In the conclusion questions are raised regarding future civil-military convergence patterns as well as possible growing differences between ranks. Keywords: military cadets, officer corps, social origins, civil-military relations. -

ATP 3-39.10. Police Operations

ATP 3-39.10 POLICE OPERATIONS AUGUST 2021 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes ATP 3-39.10, 26 January 2015. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https:// armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *ATP 3-39.10 Army Techniques Publication Headquarters No. 3-39.10 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 24 August 2021 Police Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 POLICE OPERATIONS SUPPORT TO ARMY OPERATIONS ............................... 1-1 The Police Operations Discipline .............................................................................. 1-1 Principles of Police Operations ................................................................................. 1-4 Rule of Law ................................................................................................................ 1-6 Command and Control of Army Law Enforcement .................................................... 1-7 Operational Environment ........................................................................................... 1-9 Unified Action ......................................................................................................... -

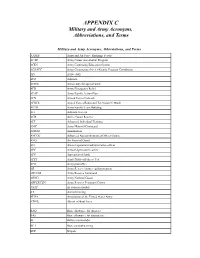

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

International Intervention and the Use of Force: Military and Police Roles

004SSRpaperFRONT_16pt.ai4SSRpaperFRONT_16pt.ai 1 331.05.20121.05.2012 117:27:167:27:16 SSR PAPER 4 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K International Intervention and the Use of Force: Military and Police Roles Cornelius Friesendorf DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law SSR PAPER 4 International Intervention and the Use of Force Military and Police Roles Cornelius Friesendorf DCAF The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) is an international foundation whose mission is to assist the international community in pursuing good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre develops and promotes norms and standards, conducts tailored policy research, identifies good practices and recommendations to promote democratic security sector governance, and provides in‐country advisory support and practical assistance programmes. SSR Papers is a flagship DCAF publication series intended to contribute innovative thinking on important themes and approaches relating to Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the broader context of Security Sector Governance (SSG). Papers provide original and provocative analysis on topics that are directly linked to the challenges of a governance‐driven security sector reform agenda. SSR Papers are intended for researchers, policy‐makers and practitioners involved in this field. ISBN 978‐92‐9222‐202‐4 © 2012 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces EDITORS Alan Bryden & Heiner Hänggi PRODUCTION Yury Korobovsky COPY EDITOR Cherry Ekins COVER IMAGE © isafmedia The views expressed are those of the author(s) alone and do not in any way reflect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper. -

Public Safety Policy in the State of Minas Gerais (2003-2016): Agenda Problems and Path Dependence

International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2018, 7, 121-134 121 Public Safety Policy in the State of Minas Gerais (2003-2016): Agenda Problems and Path Dependence Ludmila Mendonça Lopes Ribeiro1,* and Ariane Gontijo Lopes2 1Department of Sociology (DSO) and Researcher of the Center for Studies on Criminality and Public Safety (CRISP), Brazil at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil 2Ph.D Candidate at the Department of Sociology (DSO), Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil Abstract: In this paper, we reconstitute the Minas Gerais state public safety policy with regard to its agenda and discontinuity over thirteen years (2003-2016). Our purpose is to present reflections that help understand the impasses which ultimately led to the burial of a reputedly successful public policy and to a return to the old way public safety has historically been managed by Brazilian federative states. Our findings inform that the priority agenda of integration promoted by the State Secretariat of Social Defense did manage to institutionalize itself for some time. Nonetheless, as the office goes through political transformations, priorities in the agenda also change, denoting path dependence, given the resumption of the institutional arrangement that existed prior to 2003, with police institutions on one side and the prison system on the other. In this context, the novelty is the permanence of prevention actions. Keywords: Public Safety, Discontinuity, Agenda Problem, Path dependence, Minas Gerais. I. INTRODUCTION The result from this historical conception on the causes of crime in Brazil was a reduction of public In national and international imaginary, Brazil safety to an excessive surveillance over certain layers stands as a nation marked by violence.