Known and Inferred Distributions of Beaked Whale Species (Cetacea: Ziphiidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

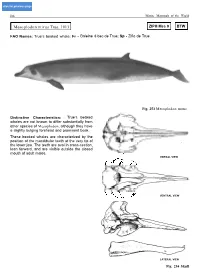

Mesoplodon Mirus True, 1913 ZIPH Mes 9 BTW

click for previous page 106 Marine Mammals of the World Mesoplodon mirus True, 1913 ZIPH Mes 9 BTW FAO Names: True’s beaked whale: Fr - Baleine à bec de True; Sp - Zifio de True. Fig. 253 Mesoplodon mirus Distinctive Characteristics: True’s beaked whales are not known to differ substantially from other species of Mesoplodon, although they have a slightly bulging forehead and prominent beak. These beaked whales are characterized by the position of the mandibular teeth at the very tip of the lower jaw. The teeth are oval in cross-section, lean forward, and are visible outside the closed mouth of adult males. DORSAL VIEW VENTRAL VIEW lLATERAL VIEWl Fig. 254 Skull Cetacea - Odontoceti - Ziphiidae 107 Can be confused with: At sea, True’s beaked whales are difficult to distinguish from other species of Mesoplodon (starting on p. 90). The only other species in which males have oval teeth at the tip of the lower jaw is Longman’s beaked whale (p. 112); whose appearance is not known. Size: Both sexes are known to reach lengths of slightly over 5 m. Weights of up to 1 400 kg have been recorded. Newborns are probably between 2 and 2.5 m. Geographical Distribution: True’s beaked whales are known only from strandings in Great Britain, from Florida to Nova Scotia in the North Atlantic, and from southeast Africa and southern Australia in the Indo-PacificcOcean. Fig. 255 Biology and Behaviour: There is almost no information available on the natural history of this species of beaked whale. Stranded animals have had squid in their stomachs. -

List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies Written by The

List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies Written by the Committee on Taxonomy The Ad-Hoc Committee on Taxonomy , chaired by Bill Perrin, has produced the first official SMM list of marine mammal species and subspecies. Consensus on some issues was not possible; this is reflected in the footnotes. This list will be revisited and possibly revised every few months reflecting the continuing flux in marine mammal taxonomy. This list can be cited as follows: “Committee on Taxonomy. 2009. List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on [date].” This list includes living and recently extinct species and subspecies. It is meant to reflect prevailing usage and recent revisions published in the peer-reviewed literature. Author(s) and year of description of the species follow the Latin species name; when these are enclosed in parentheses, the species was originally described in a different genus. Classification and scientific names follow Rice (1998), with adjustments reflecting more recent literature. Common names are arbitrary and change with time and place; one or two currently frequently used in English and/or a range language are given here. Additional English common names and common names in French, Spanish, Russian and other languages are available at www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/ . The cetaceans genetically and morphologically fall firmly within the artiodactyl clade (Geisler and Uhen, 2005), and therefore we include them in the order Cetartiodactyla, with Cetacea, Mysticeti and Odontoceti as unranked taxa (recognizing that the classification within Cetartiodactyla remains partially unresolved -- e.g., see Spaulding et al ., 2009) 1. -

Genetic Structure of the Beaked Whale Genus Berardius in the North Pacific

MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, 33(1): 96–111 (January 2017) Published 2016. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA DOI: 10.1111/mms.12345 Genetic structure of the beaked whale genus Berardius in the North Pacific, with genetic evidence for a new species PHILLIP A. MORIN1, Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Cen- ter, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 8901 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A. and Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A.; C. SCOTT BAKER Marine Mammal Institute and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, 2030 SE Marine Science Drive, Newport, Oregon 07365, U.S.A.; REID S. BREWER Fisheries Technology, University of Alaska South- east, 1332 Seward Avenue, Sitka, Alaska 99835, U.S.A.; ALEXANDER M. BURDIN Kam- chatka Branch of the Pacific Geographical Institute, Partizanskaya Str. 6, Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky, 683000 Russia; MEREL L. DALEBOUT School of Biological, Earth, and Environ- mental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia; JAMES P. DINES Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, U.S.A.; IVAN D. FEDUTIN AND OLGA A. FILATOVA Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, Moscow 119992, Russia; ERICH HOYT Whale and Dol- phin Conservation, Park House, Allington Park, Bridport, Dorset DT6 5DD, United King- dom; JEAN-LUC JUNG Laboratoire BioGEMME, Universite de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France; MORGANE LAUF Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 8901 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, California 92037, U.S.A.; CHARLES W. -

Order CETACEA Suborder MYSTICETI BALAENIDAE Eubalaena Glacialis (Müller, 1776) EUG En - Northern Right Whale; Fr - Baleine De Biscaye; Sp - Ballena Franca

click for previous page Cetacea 2041 Order CETACEA Suborder MYSTICETI BALAENIDAE Eubalaena glacialis (Müller, 1776) EUG En - Northern right whale; Fr - Baleine de Biscaye; Sp - Ballena franca. Adults common to 17 m, maximum to 18 m long.Body rotund with head to 1/3 of total length;no pleats in throat; dorsal fin absent. Mostly black or dark brown, may have white splotches on chin and belly.Commonly travel in groups of less than 12 in shallow water regions. IUCN Status: Endangered. BALAENOPTERIDAE Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacepède, 1804 MIW En - Minke whale; Fr - Petit rorqual; Sp - Rorcual enano. Adult males maximum to slightly over 9 m long, females to 10.7 m.Head extremely pointed with prominent me- dian ridge. Body dark grey to black dorsally and white ventrally with streaks and lobes of intermediate shades along sides.Commonly travel singly or in groups of 2 or 3 in coastal and shore areas;may be found in groups of several hundred on feeding grounds. IUCN Status: Lower risk, near threatened. Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828 SIW En - Sei whale; Fr - Rorqual de Rudolphi; Sp - Rorcual del norte. Adults to 18 m long. Typical rorqual body shape; dorsal fin tall and strongly curved, rises at a steep angle from back.Colour of body is mostly dark grey or blue-grey with a whitish area on belly and ventral pleats.Commonly travel in groups of 2 to 5 in open ocean waters. IUCN Status: Endangered. 2042 Marine Mammals Balaenoptera edeni Anderson, 1878 BRW En - Bryde’s whale; Fr - Rorqual de Bryde; Sp - Rorcual tropical. -

Cetaceans: Whales and Dolphins

CETACEANS: WHALES AND DOLPHINS By Anna Plattner Objective Students will explore the natural history of whales and dolphins around the world. Content will be focused on how whales and dolphins are adapted to the marine environment, the differences between toothed and baleen whales, and how whales and dolphins communicate and find food. Characteristics of specific species of whales will be presented throughout the guide. What is a cetacean? A cetacean is any marine mammal in the order Cetaceae. These animals live their entire lives in water and include whales, dolphins, and porpoises. There are 81 known species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. The two suborders of cetaceans are mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (toothed whales). Cetaceans are mammals, thus they are warm blooded, give live birth, have hair when they are born (most lose their hair soon after), and nurse their young. How are cetaceans adapted to the marine environment? Cetaceans have developed many traits that allow them to thrive in the marine environment. They have streamlined bodies that glide easily through the water and help them conserve energy while they swim. Cetaceans breathe through a blowhole, located on the top of their head. This allows them to float at the surface of the water and easily exhale and inhale. Cetaceans also have a thick layer of fat tissue called blubber that insulates their internals organs and muscles. The limbs of cetaceans have also been modified for swimming. A cetacean has a powerful tailfin called a fluke and forelimbs called flippers that help them steer through the water. Most cetaceans also have a dorsal fin that helps them stabilize while swimming. -

FC Inshore Cetacean Species Identification

Falklands Conservation PO BOX 26, Falkland Islands, FIQQ 1ZZ +500 22247 [email protected] www.falklandsconservation.com FC Inshore Cetacean Species Identification Introduction This guide outlines the key features that can be used to distinguish between the six most common cetacean species that inhabit Falklands' waters. A number of additional cetacean species may occasionally be seen in coastal waters, for example the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas) and the dusky dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obscurus). A full list of the species that have been documented to date around the Falklands can be found in Appendix 1. Note that many of these are typical of deeper, oceanic waters, and are unlikely to be encountered along the coast. The six species (or seven species, including two species of minke whale) described in this document are observed regularly in shallow, nearshore waters, and are the focus of this identification guide. Questions and further information For any questions about species identification then please contact the Cetaceans Project Officer Caroline Weir who will be happy to help you try and identify your sighting: Tel: 22247 Email: [email protected] Useful identification guides If you wish to learn more about the identification features of various species, some comprehensive field guides (which include all cetacean species globally) include: Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises by Mark Carwardine. 2019. Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification by Thomas A. Jefferson, Marc A. Webber, and Robert L. Pitman. 2015. Whales, Dolphins and Seals: A Field Guide to the Marine Mammals of the World by Hadoram Shirihai and Brett Jarrett. -

Fall12 Rare Southern California Sperm Whale Sighting

Rare Southern California Sperm Whale Sighting Dolphin/Whale Interaction Is Unique IN MAY 2011, a rare occurrence The sperm whale sighting off San of 67 minutes as the whales traveled took place off the Southern California Diego was exciting not only because slowly east and out over the edge of coast. For the first time since U.S. of its rarity, but because there were the underwater ridge. The adult Navy-funded aerial surveys began in also two species of dolphins, sperm whales undertook two long the area in 2008, a group of 20 sperm northern right whale dolphins and dives lasting about 20 minutes each; whales, including four calves, was Risso’s dolphins, interacting with the the calves surfaced earlier, usually in seen—approximately 24 nautical sperm whales in a remarkable the company of one adult whale. miles west of San Diego. manner. To the knowledge of the During these dives, the dolphins researchers who conducted this aerial remained at the surface and Operating under a National Marine survey, this type of inter-species asso- appeared to wait for the sperm Fisheries Service (NMFS) permit, the ciation has not been previously whales to re-surface. U.S. Navy has been conducting aerial reported. Video and photographs surveys of marine mammal and sea Several minutes after the sperm were taken of the group over a period turtle behavior in the near shore and whales were first seen, the Risso’s offshore waters within the Southern California Range Complex (SOCAL) since 2008. During a routine survey the morning of 14 May 2011, the sperm whales were sighted on the edge of an offshore bank near a steep drop-off. -

Passive Acoustics Survey of Cetacean Abundance Levels (PASCAL-2016) Final Report

OCS Study BOEM 2018-025 Passive Acoustics Survey of Cetacean Abundance Levels (PASCAL-2016) Final Report US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2018-025 Passive Acoustics Survey of Cetacean Abundance Levels (PASCAL-2016) Final Report June 2018 Authors: Jennifer L. Keating1, 2, Jay Barlow3, Emily T. Griffiths4, Jeffrey E. Moore3 Prepared under Interagency Agreement M16PG00011 By 1 Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1845 Wasp Boulevard Honolulu, HI 96818 2 Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research University of Hawaii 1000 Pope Road Honolulu, HI 96822 3 Marine Mammal and Turtle Division Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 8901 La Jolla Shores Drive La Jolla, CA 92037 4 Ocean Associates Inc. 4007 N Abingdon Street Arlington, VA 22207 US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M16PG00011 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Data and Information Systems webpage (https://www.boem.gov/Environmental-Studies- EnvData/), click on the link for the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS), and search on 2018-025. -

Whale Identification Posters

Whale dorsal fins Humpback whale Sperm whale Photo: Nadine Bott Photo: Whale Watch Kaikoura Blue whale Southern right whale (no dorsal) Photo: Nadine Bott Photo: Nadine Bott False killer whale Pilot whale Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar • Report all marine mammal sightings to DOC via the online sighting form (www.doc.govt.nz/marinemammalsightings) • Email photos of marine mammal sightings to [email protected] Thank you for your help! 24hr emergency hotline Orca Photo: Ailie Suzuki Keep your distance – do not approach closer than 50 m to whales Whale tail flukes Humpback whale Sperm whale Photo: Nadine Bott Photo: Nadine Bott Blue whale Southern right whale Photo: Gregory Smith (CC BY-SA 2.0) Photo: Tui De Roy False killer whale Pilot whale Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar • Report all marine mammal sightings to DOC via the online sighting form (www.doc.govt.nz/marinemammalsightings) • Email photos of marine mammal sightings to [email protected] Thank you for your help! 24hr emergency hotline Orca Photo: Nadine Bott Keep your distance – do not approach closer than 50 m to whales Whale surface behaviour Humpback whale Sperm whale Photo: Nadine Bott Photo: Whale Watch Kaikoura Blue whale Southern right whale Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar Photo: Don Goodhue False killer whale Pilot whale Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar Photo: Jochen Zaeschmar • Report all marine mammal sightings to DOC via the online sighting form (www.doc.govt.nz/marinemammalsightings) • Email photos of marine mammal sightings to [email protected] -

Navy Gulf of Alaska Testing and Training 2017 Rule Application

REQUEST FOR LETTER OF AUTHORIZATION FOR THE INCIDENTAL HARASSMENT OF MARINE MAMMALS RESULTING FROM U.S. NAVY TRAINING ACTIVITIES IN THE GULF OF ALASKA TEMPORARY MARITIME ACTIVITIES AREA Submitted to: Office of Protected Resources National Marine Fisheries Service 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-3226 Submitted by: Commander, United States Pacific Fleet 250 Makalapa Drive Pearl Harbor, Hawaii 96860-3131 Revised Revised January 21, 2015 January 21, 2015 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Request for Letters of Authorization for the Incidental Harassment of Marine Mammals Resulting from Navy Training Activities in the Gulf of Alaska Temporary Maritime Activities Area TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTION OF ACTIVITIES ......................................................................1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1-3 1.3 OVERVIEW OF TRAINING ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................1-3 1.3.1 DESCRIPTION OF CURRENT TRAINING ACTIVITIES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA .................................................. 1-3 1.3.1.1 Anti-Surface Warfare .................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3.1.2 Anti-Submarine Warfare ............................................................................................................ -

Southern Right Whale Recovery Plan 2005

SOUTHERN RIGHT WHALE RECOVERY PLAN 2005 - 2010 The southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) is listed as endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). This plan outlines the measures necessary to ensure recovery of the Australian population of southern right whales and is set out in accordance with Part 13, Division 5 of the EPBC Act. Objectives for recovery The objectives are: • the recovery of the southern right whale population utilising Australian waters so that the population can be considered secure in the wild; • a distribution of southern right whales utilising Australian waters that is similar to the pre- exploitation distribution of the species; and • to maintain the protection of southern right whales from human threats. For the purposes of this plan ‘secure in the wild’ is defined qualitatively, recognising that stricter definitions are not yet available, but will be refined and where possible quantified during the life of this plan by work currently underway and identified in the actions of this plan. ‘Secure in the wild’ with respect to southern right whales in Australian waters means: a population with sufficient geographic range and distribution, abundance, and genetic diversity to provide a stable population over long time scales. Criteria to measure performance of the plan against the objectives It is not anticipated that the objectives for recovery will be achieved during the life of this plan. However, the following criteria can be used to measure the ongoing performance of this plan against the objectives: 1. the Australian population of southern right whales continued to recover at, or close to, the optimum biological rate (understood to be approximately 7% per annum at the commencement of this plan); 2. -

Whale Watching New South Wales Australia

Whale Watching New South Wales Australia Including • About Whales • Humpback Whales • Whale Migration • Southern Right Whales • Whale Life Cycle • Blue Whales • Whales in Sydney Harbour • Minke Whales • Aboriginal People & Whales • Dolphins • Typical Whale Behaviour • Orcas • Whale Species • Other Whale Species • Whales in Australia • Other Marine Species About Whales The whale species you are most likely to see along the New South Wales Coastline are • Humpback Whale • Southern Right Whale Throughout June and July Humpback Whales head north for breading before return south with their calves from September to November. Other whale species you may see include: • Minke Whale • Blue Whale • Sei Whale • Fin Whale • False Killer Whale • Orca or Killer Whale • Sperm Whale • Pygmy Right Whale • Pygmy Sperm Whale • Bryde’s Whale Oceans cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface and this vast environment is home to some of the Earth’s most fascinating creatures: whales. Whales are complex, often highly social and intelligent creatures. They are mammals like us. They breath air, have hair on their bodies (though only very little), give birth to live young and suckle their calves through mammary glands. But unlike us, whales are perfectly adapted to the marine environment with strong, muscular and streamlined bodies insulated by thick layers of blubber to keep them warm. Whales are gentle animals that have graced the planet for over 50 million years and are present in all oceans of the world. They capture our imagination like few other animals. The largest species of whales were hunted almost to extinction in the last few hundred years and have survived only thanks to conservation and protection efforts.