Case Reports NSTEMI in a 28-Year-Old Female with Recent Myocarditis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiac Involvement in COVID-19 Patients: a Contemporary Review

Review Cardiac Involvement in COVID-19 Patients: A Contemporary Review Domenico Maria Carretta 1, Aline Maria Silva 2, Donato D’Agostino 2, Skender Topi 3, Roberto Lovero 4, Ioannis Alexandros Charitos 5,*, Angelika Elzbieta Wegierska 6, Monica Montagnani 7,† and Luigi Santacroce 6,*,† 1 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Coronary Unit and Electrophysiology/Pacing Unit, Cardio-Thoracic Department, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 2 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Cardiac Surgery, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (A.M.S.); [email protected] (D.D.) 3 Department of Clinical Disciplines, School of Technical Medical Sciences, University of Elbasan “A. Xhuvani”, 3001 Elbasan, Albania; [email protected] 4 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Clinical Pathology Unit, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 5 Emergency/Urgent Department, National Poisoning Center, Riuniti University Hospital of Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy 6 Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, Microbiology and Virology Unit, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Piazza G. Cesare, 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 7 Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology—Section of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, p.zza G. Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.C.); [email protected] (L.S.) † These authors equally contributed as co-last authors. Citation: Carretta, D.M.; Silva, A.M.; D’Agostino, D.; Topi, S.; Lovero, R.; Charitos, I.A.; Wegierska, A.E.; Abstract: Background: The widely variable clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV2 disease (COVID-19) Montagnani, M.; Santacroce, L. -

Myocarditis and Cardiomyopathy

CE: Tripti; HCO/330310; Total nos of Pages: 6; HCO 330310 REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy Jonathan Buggey and Chantal A. ElAmm Purpose of review The aim of this study is to summarize the literature describing the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of cardiomyopathy related to myocarditis. Recent findings Myocarditis has a variety of causes and a heterogeneous clinical presentation with potentially life- threatening complications. About one-third of patients will develop a dilated cardiomyopathy and the pathogenesis is a multiphase, mutlicompartment process that involves immune activation, including innate immune system triggered proinflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies. In recent years, diagnosis has been aided by advancements in cardiac MRI, and in particular T1 and T2 mapping sequences. In certain clinical situations, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) should be performed, with consideration of left ventricular sampling, for an accurate diagnosis that may aid treatment and prognostication. Summary Although overall myocarditis accounts for a minority of cardiomyopathy and heart failure presentations, the clinical presentation is variable and the pathophysiology of myocardial damage is unique. Cardiac MRI has significantly improved diagnostic abilities, but endomyocardial biopsy remains the gold standard. However, current treatment strategies are still focused on routine heart failure pharmacotherapies and supportive care or cardiac transplantation/mechanical support for those with end-stage heart failure. Keywords cardiac MRI, cardiomyopathy, endomyocardial biopsy, myocarditis INTRODUCTION prevalence seen in children and young adults aged Myocarditis refers to inflammation of the myocar- 20–30 years [1]. dium and may be caused by infectious agents, systemic diseases, drugs and toxins, with viral infec- CAUSE tions remaining the most common cause in the developed countries [1]. -

Myocarditis, Pericarditis and Other Pericardial Diseases

Heart 2000;84:449–454 Diagnosis is easiest during epidemics of cox- GENERAL CARDIOLOGY sackie infections but diYcult in isolated cases. Heart: first published as 10.1136/heart.84.4.449 on 1 October 2000. Downloaded from These are not seen by cardiologists unless they develop arrhythmia, collapse or suVer chest Myocarditis, pericarditis and other pain, the majority being dealt with in the primary care system. pericardial diseases Acute onset of chest pain is usual and may mimic myocardial infarction or be associated 449 Celia M Oakley with pericarditis. Arrhythmias or conduction Imperial College School of Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, disturbances may be life threatening despite London, UK only mild focal injury, whereas more wide- spread inflammation is necessary before car- diac dysfunction is suYcient to cause symp- his article discusses the diagnosis and toms. management of myocarditis and peri- Tcarditis (both acute and recurrent), as Investigations well as other pericardial diseases. The ECG may show sinus tachycardia, focal or generalised abnormality, ST segment eleva- tion, fascicular blocks or atrioventricular con- Myocarditis duction disturbances. Although the ECG abnormalities are non-specific, the ECG has Myocarditis is the term used to indicate acute the virtue of drawing attention to the heart and infective, toxic or autoimmune inflammation of leading to echocardiographic and other investi- the heart. Reversible toxic myocarditis occurs gations. Echocardiography may reveal segmen- in diphtheria and sometimes in infective endo- -

Myocarditis and Mrna Vaccines

Updated June 28, 2021 DOH 348-828 Information for Clinical Staff: Myocarditis and mRNA Vaccines This document helps clinicians understand myocarditis and its probable link to some COVID-19 vaccines. It provides talking points clinicians can use when discussing the benefits and risks of these vaccines with their patients and offers guidance on what to do if they have a patient who presents with myocarditis following vaccination. Myocarditis information What are myocarditis and pericarditis? • Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle. • Pericarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle covering. • The body’s immune system can cause inflammation often in response to an infection. The body’s immune system can cause inflammation after other things as well. What is the connection to COVID-19 vaccination? • A CDC safety panel has determined there is a “probable association” between myocarditis and pericarditis and the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, made by Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, in some vaccine recipients. • Reports of myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination are rare. • Cases have mostly occurred in adolescents and young adults under the age of 30 years and mostly in males. • Most patients who developed myocarditis after vaccination responded well to rest and minimal treatment. Talking Points for Clinicians The risk of myocarditis is low, especially compared to the strong benefits of vaccination. • Hundreds of millions of vaccine doses have safely been given to people in the U.S. To request this document in another format, call 1-800-525-0127. Deaf or hard of hearing customers, please call 711 (Washington Relay) or email [email protected]. -

Heart Valve Disease: Mitral and Tricuspid Valves

Heart Valve Disease: Mitral and Tricuspid Valves Heart anatomy The heart has two sides, separated by an inner wall called the septum. The right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen. The left side of the heart receives the oxygen- rich blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body. The heart has four chambers and four valves that regulate blood flow. The upper chambers are called the left and right atria, and the lower chambers are called the left and right ventricles. The mitral valve is located on the left side of the heart, between the left atrium and the left ventricle. This valve has two leaflets that allow blood to flow from the lungs to the heart. The tricuspid valve is located on the right side of the heart, between the right atrium and the right ventricle. This valve has three leaflets and its function is to Cardiac Surgery-MATRIx Program -1- prevent blood from leaking back into the right atrium. What is heart valve disease? In heart valve disease, one or more of the valves in your heart does not open or close properly. Heart valve problems may include: • Regurgitation (also called insufficiency)- In this condition, the valve leaflets don't close properly, causing blood to leak backward in your heart. • Stenosis- In valve stenosis, your valve leaflets become thick or stiff, and do not open wide enough. This reduces blood flow through the valve. Blausen.com staff-Own work, CC BY 3.0 Mitral valve disease The most common problems affecting the mitral valve are the inability for the valve to completely open (stenosis) or close (regurgitation). -

Currentstateofknowledgeonaetiol

European Heart Journal (2013) 34, 2636–2648 ESC REPORT doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht210 Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases Downloaded from Alida L. P. Caforio1†*, Sabine Pankuweit2†, Eloisa Arbustini3, Cristina Basso4, Juan Gimeno-Blanes5,StephanB.Felix6,MichaelFu7,TiinaHelio¨ 8, Stephane Heymans9, http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ Roland Jahns10,KarinKlingel11, Ales Linhart12, Bernhard Maisch2, William McKenna13, Jens Mogensen14, Yigal M. Pinto15,ArsenRistic16, Heinz-Peter Schultheiss17, Hubert Seggewiss18, Luigi Tavazzi19,GaetanoThiene4,AliYilmaz20, Philippe Charron21,andPerryM.Elliott13 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Cardiological Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy; 2Universita¨tsklinikum Gießen und Marburg GmbH, Standort Marburg, Klinik fu¨r Kardiologie, Marburg, Germany; 3Academic Hospital IRCCS Foundation Policlinico, San Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 4Cardiovascular Pathology, Department of Cardiological Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy; 5Servicio de Cardiologia, Hospital U. Virgen de Arrixaca Ctra. Murcia-Cartagena s/n, El Palmar, Spain; 6Medizinische Klinik B, University of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; 7Department of Medicine, Heart Failure Unit, Sahlgrenska Hospital, University of Go¨teborg, Go¨teborg, Sweden; 8Division of Cardiology, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Heart & Lung Centre, -

Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary Artery Disease INFORMATION GUIDE Other names: Atherosclerosis CAD Coronary heart disease (CHD) Hardening of the arteries Heart disease Ischemic (is-KE-mik) heart disease Narrowing of the arteries The purpose of this guide is to help patients and families find sources of information and support. This list is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide starting points for information seeking. The resources may be obtained at the Mardigian Wellness Resource Center located off the Atrium on Floor 2 of the Cardiovascular Center. Visit our website at http://www.umcvc.org/mardigian-wellness-resource-center and online Information guides at http://infoguides.med.umich.edu/home Books, Brochures, Fact Sheets Michigan Medicine. What is Ischemic Heart Disease and Stroke. http://www.med.umich.edu/1libr/CCG/IHDshort.pdf National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). In Brief: Your Guide to Living Well with Heart Disease. A four-page fact sheet. Available online at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/other/your_guide/living_hd_f s.pdf National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Your Guide to Living Well with Heart Disease. A 68-page booklet is a step-by-step guide to helping people with heart disease make decisions that will protect and improve their lives A printer- friendly version is available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/other/your_guide/living_well. pdf Coronary Artery Disease Page 1 Mardigian Wellness Resource Center Coronary Artery Disease INFORMATION GUIDE Books Bale, Bradley. Beat the Heart Attack Gene: A Revolutionary Plan to Prevent Heart Disease, Stroke and Diabetes. New York, NY: Turner Publishing, 2014. -

Association of Cardiomegaly with Coronary Artery Histopathology and Its Relationship to Atheroma

32 Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis Vol.18, No.1 Coronary Histopathology in Cardiomegaly 33 Original Article Association of Cardiomegaly with Coronary Artery Histopathology and its Relationship to Atheroma Richard Everett Tracy Department of Pathology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, USA Aims: Hypertrophied hearts at autopsy often display excessive coronary artery atherosclerosis, but the histopathology of coronary arteries in hearts with and without cardiomegaly has rarely been com- pared. Methods: In this study, forensic autopsies provided hearts with unexplained enlargement plus com- parison specimens. Right coronary artery was opened longitudinally and flattened for formalin fixa- tion and H&E-stained paraffin sections were cut perpendicular to the endothelial surface. The mi- croscopically observed presence or absence of a necrotic atheroma in the specimen was recorded. At multiple sites far removed from any form of atherosclerosis, measurements were taken of intimal thickness, numbers of smooth muscle cells (SMC) and their ratio, the thickness per SMC, averaged over the entire nonatheromatous arterial length. When the mean thickness per SMC exceeded a cer- tain cutoff point, the artery was declared likely to contain a necrotic atheroma. Results: The prevalence of specimens with necrotic atheromas increased stepwise with increasing heart weight, equally with fatal or with incidental cardiomegaly, and equally with hypertension- or obesity-related hypertrophy, rejecting further inclusion of appreciable age, race, or gender effects. The prevalence of specimens with thickness per SMC exceeding the cutoff point was almost always nearly identical to the prevalence of observed necrotic atheroma, showing the two variables to be tightly linked to each other with quantitative consistency across group comparisons of every form. -

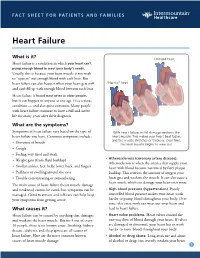

Heart Failure

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Heart Failure What is it? Enlarged heart Heart failure is a condition in which your heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Usually, this is because your heart muscle is too weak to “squeeze” out enough blood with each beat. But heart failure can also happen when your heart gets stiff “Normal” heart and can’t fill up with enough blood between each beat. Heart failure is found most often in older people, but it can happen to anyone at any age. It’s a serious condition — and also quite common. Many people with heart failure continue to have a full and active life for many years after their diagnosis. What are the symptoms? Symptoms of heart failure vary based on the type of With heart failure, initial damage weakens the heart failure you have. Common symptoms include: heart muscle. This makes your heart beat faster, and the muscle stretches or thickens. Over time, • Shortness of breath the heart muscle begins to wear out. • Cough • Feeling very tired and weak • Atherosclerosis (coronary artery disease). • Weight gain (from fluid buildup) Atherosclerosis is when the arteries that supply your • Swollen ankles, feet, belly, lower back, and fingers heart with blood become narrowed by fatty plaque • Puffiness or swelling around the eyes buildup. This restricts the amount of oxygen your • Trouble concentrating or remembering heart gets and weakens the muscle. It can also cause a heart attack, which can damage your heart even more. The main cause of heart failure (heart muscle damage and weakness) cannot be cured, but symptoms can be • High blood pressure (hypertension). -

Severe Acute Mitral Valve Regurgitation in a COVID-19-Infected Patient

Case report BMJ Case Rep: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2020-239782 on 18 January 2021. Downloaded from Severe acute mitral valve regurgitation in a COVID- 19- infected patient Ayesha Khanduri, Usha Anand, Maged Doss, Louis Lovett Graduate Medical Education, SUMMARY damage leading to pulmonary oedema and respira- WellStar Health System, The ongoing SARS- CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has tory failure secondary to congestive heart failure. In Marietta, Georgia, USA presented many difficult and unique challenges to the these patients, a broader differential for pulmonary medical community. We describe a case of a middle- aged oedema and respiratory failure must be considered Correspondence to to ensure timely and appropriate treatment. Dr Ayesha Khanduri; COVID-19- positive man who presented with pulmonary ayesha. khanduri@ wellstar. org oedema and acute respiratory failure. He was initially diagnosed with acute respiratory distress syndrome. CASE PRESENTATION Accepted 3 December 2020 Later in the hospital course, his pulmonary oedema and A middle-aged man presented to the emergency respiratory failure worsened as result of severe acute department with progressively worsening short- mitral valve regurgitation secondary to direct valvular ness of breath, a non-productive cough and hypox- damage from COVID-19 infection. The patient underwent emia. His medical history was significant for atrial emergent surgical mitral valve replacement. Pathological flutter status post ablation in 2017. The patient evaluation of the damaged valve was confirmed to be is a lifelong non- smoker who bikes 2 miles daily. secondary to COVID-19 infection. The histopathological At that time in 2017, an echocardiogram revealed findings were consistent with prior cardiopulmonary mild mitral valve regurgitation with a normal left autopsy sections of patients with COVID-19 described ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF >55%). -

COVID 19 Vaccine for Adolescents. Concern About Myocarditis and Pericarditis

Opinion COVID 19 Vaccine for Adolescents. Concern about Myocarditis and Pericarditis Giuseppe Calcaterra 1, Jawahar Lal Mehta 2 , Cesare de Gregorio 3 , Gianfranco Butera 4, Paola Neroni 5, Vassilios Fanos 5 and Pier Paolo Bassareo 6,* 1 Department of Cardiology, Postgraduate Medical School of Cardiology, University of Palermo, 90127 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy; [email protected] 4 Cardiology, Cardiac Surgery, and Heart Lung Transplantation Department, ERN, GUAR HEART, Bambino Gesu’ Hospital and Research Institute, IRCCS Rome, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 5 Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Department of Surgical Sciences, Policlinico Universitario di Monserrato, University of Cagliari, 09042 Monserrato, Italy; [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (V.F.) 6 Department of Cardiology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital and Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin, University College of Dublin, School of Medicine, D07R2WY Dublin, Ireland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +353-1409-6083 Abstract: The alarming onset of some cases of myocarditis and pericarditis following the adminis- tration of Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines in adolescent males has recently been highlighted. All occurred after the second dose of the vaccine. Fortunately, none of Citation: Calcaterra, G.; Mehta, J.L.; patients were critically ill and each was discharged home. Owing to the possible link between these de Gregorio, C.; Butera, G.; Neroni, P.; cases and vaccine administration, the US and European health regulators decided to continue to Fanos, V.; Bassareo, P.P. -

Basic Mechanisms of Myocarditis KIRK U

Basic Mechanisms of Myocarditis KIRK U. KNOWLTON, M.D. INTERMOUNTAIN MEDICAL CENTER, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Major mechanisms that contribute to myocarditis Infection Virus Bacteria Parasites Immune activation against infectious pathogens Innate immunity Adaptive immunity Primary immune mechanisms Myocyte injury Antigen mimicry Hypersensitivity reactions Causes of Myocarditis Checkpoint inhibitors Are there common questions between viral myocarditis and checkpoint-inhibitor mediated myocarditis? Low incidence of myocarditis in patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors A very small percentage of patients that receive checkpoint inhibitors develop myocarditis- 0.09% or 0.27% of patients treated single checkpoint inhibitors or combination checkpoint inhibitors, respectively. Low incidence of myocarditis in patients infected with viruses that are known to cause myocarditis While many patients are infected with common viruses such as Coxsackievirus, adenovirus, parvovirus, herpes virus, Epstein-Barr virus, only a very small percentage actually develop myocarditis Why? Potential genetic variants/ mutations Innate immunity Adaptive immunity Sarcolemmal membrane integrity Other factors Underlying infection Nutrition Age Pregnancy Hormones The incidence of disease is likely affected by a combination of multiple influences Therefore, Review mechanisms that have been shown to cause myocarditis And, those that increase susceptibility to myocarditis SCIENCE VOL 291 12 JANUARY 2001 Nature