Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

The Systematic Identification and Articulation of Content Standards and Benchmarks. Update. INSTITUTION Mid-Continent Regional Educational Lab., Aurora, CO

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 403 308 TM 026 040 AUTHOR Kendall, John S.; Marzano, Robert J. TITLE The Systematic Identification and Articulation of Content Standards and Benchmarks. Update. INSTITUTION Mid-Continent Regional Educational Lab., Aurora, CO. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Mar 95 CONTRACT RP91002005 NOTE 598p. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art; *Course Content; *Educational Improvement; Elementary Secondary Education; Geography Instruction; Health Education; History Instruction; *Identification; Language Arts; Mathematics Education; Science Education; *Standards; Thinking Skills IDENTIFIERS *Benchmarking; *Subject Content Knowledge ABSTRACT The project described in this paper addresses the major issues surrounding content standards, provides a model for their identification, and applies this model to identify standards and benchmarks in subject areas. This update includes a revision of content standards and benchmarks published in, earlier updates and the synthesis and identification of standards in new areas. Standards and benchmarks are provided for science, mathematics, history, geography, the arts, the language arts, and health. Also included are standards in thinking and reasoning and an analysis and description of knowledge and skills considered important for the workplace. Following an introduction, the second section presents an overview of the current efforts towards standards in each of these subject areas. Section 3 describes the technical and conceptual differences that have been apparent in the standards movement and the model adopted for this study. Section 4 presents key questions that should be addressed by schools and districts interested in a standards-based strategy. -

Univer^ Micrèïilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

The U.S. Homeland Security Role in the Mexican War Against Drug Cartels

THE U.S. HOMELAND SECURITY ROLE IN THE MEXICAN WAR AGAINST DRUG CARTELS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 31, 2011 Serial No. 112–14 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–224 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia VACANCY BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director/Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT MICHAEL T. -

Sandspur, Vol. 78 No. 17, March 06, 1972

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 3-6-1972 Sandspur, Vol. 78 No. 17, March 06, 1972 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol. 78 No. 17, March 06, 1972" (1972). The Rollins Sandspur. 1417. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1417 >- COLLECT^ *EMf TRADE. 9EM-' BUT m DON'T VOTE ^ FOR /* •EM' In This Week's Issue: National Takes - p. 2 & 3 From Above Ground - p. 4 Letters - p. 5 The Music Corner - p. 6 Mr. Alphonse Carlo - p. 7 Institutional Self-Study - p. 8 A Look At Three Pols - p. 9 Student Center Concerns - p. 10 Presidential & Vice-Presidential Candidates - p. 11 & 12 An Open Letter To All Students - p. 13 Assembly Notes - p. 13 Who Is Lilian Harvey? - p. 14 William Kunstler - p. 15 Something Different - p. 16 & 17 National Takes SUNY BUFFALO CAMPUS COPS ACCUSED OF VANDALISM BUFFALO (CPS) - The campus security officers at the State University of New York at Buffalo have been accused of conducting an un authorized search of an alternative campus news paper, The Undercurrent. The Undercurrent staff accused Campus Secu rity of conducting an unauthorized search of their office in the early morning of January 27. -

Secret Honor – Illustrated Screenplay

Secret Honor – Illustrated Screenplay directed by Robert Altman © Sandcastle 5 Productions, Inc., 1984 © 2004 The Criterion Collection [Transcribed from the movie by Tara Carreon] YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS. This work is a fictional meditation concerning the character of and events in the history of Richard M. Nixon, who is impersonated in this film. The dramatist’s imagination has created some fictional events in an effort to illuminate the character of President Nixon. This film is not a work of history or a historical recreation. It is a work of fiction, using as a fictional character a real person, President Richard M. Nixon – in an attempt to understand. [Clock Chiming] SANDCASTLE 5 PRODUCTIONS, INC. in cooperation with UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION and the LOS ANGELES ACTORS’ THEATRE presents PHILIP BAKER HALL in SECRET HONOR A Political Myth [Door Lock Unlocking] Musical Score by GEORGE BURT Art Director STEPHEN ALTMAN Editor JULIET WEBER Director of Photography PIERRE MIGNOT Associate Director ROBERT HARDERS Executive Producer SCOTT BUSHNELL Written by DONALD FREED and ARNOLD M. STONE Produced and Directed by ROBERT ALTMAN [President Richard Nixon] Um, testing. -

April 16-30, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/26/1972 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/28/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/29/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/30/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/20/1972 A Appendix “C” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/24/1972 A Appendix “A” 7 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 4/27/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary April 16, 1972 – April 30, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) 1H£ WHITE: HOUS£ PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Trani Record for Trani ActivilY) I'LACE DAY BEGAN DATIl (Mo., Day, Yr.) APRIL 16, 1972 THE WHITE HOUSE TIMll DAY WASHINGTON. -

Crooked Kaleidoscope Organized Crime in the Balkans

CrookedCrooked KaleidoscopeKaleidoscope OrganizedOrganized CrimeCrime inin thethe BalkansBalkans June 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS Crooked Kaleidoscope Organized Crime in the Balkans June 2017 © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgements The author would like to thank, among others, Erhard Busek, Tim Del Vecchio, Odd Berner Malme, Goran Svilanovic, Ivan Krastev, Guy Vinet and colleagues in the OSCE Strategic Police Matters Unit, Gerald Tatzgern, Robert Hampshire, Christian Jechoutek, Norbert Mappes-Niediek, Thomas Pietschmann, Svein Eriksen, Ugi Zvekic, as well as colleagues at EUROPOL, the OSCE, UNHCR and UNODC. A big thank you to Sharon Wilson for layout, Sebastian Ballard for the maps, and to Ray Bartkus as always for a fantastic cover. A special tribute to the many brave journalists and members of civil society, particularly in Macedonia and Montenegro, who would prefer to remain anonymous. Thanks to Mark Shaw and Tuesday Reitano at the Global Initiative for their support and encouragement to make this paper possible. The Global Initiative would like to thank the Government of Norway for the funding provided for catalytic research on illicit flows and zones of fragility that made this study possible. About the Author Walter Kemp is a Senior Fellow at the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. -

President Nixon's Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar's Mayoral Years

President Nixon’s Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar’s Mayoral Years and Rise to National Politics By Kelsey Green University of Indianapolis Undergraduate History Program, Spring 2021 Undergraduate Status: Senior [email protected] Green 1 A WARM HOOSIER WELCOME On February 5th, 1970 at 12:20 in the afternoon, President Richard Milhous Nixon landed in Indianapolis, Indiana. Nixon was accompanied in Air Force One by First Lady Pat Nixon, Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary George W. Romney, and his top aides H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman among others. His other advisor, Daniel P. Moynihan, would rendezvous with the presidential entourage later that day.i Awaiting his arrival on the tarmac, Governor Edgar Whitcomb and Mayor Richard Lugar led the local reception committee. Donning winter overcoats, the president and Mayor Lugar are seen cordially greeting one another in a striking black and white photo. On the left, the young Lugar extends his hand to a much older and harried Nixon. Both men are smiling and framed by a large camera and microphone to record this historic moment.ii Nixon would later remark that he was received with a “warm Hoosier welcome on a rather cold day.”iii This was the first time Nixon had visited Indianapolis as president and was his first publicized meeting with Mayor Lugar, the up-and-coming politician who now represented the revitalized Republican Party in Indianapolis. After exchanging pleasantries and traveling to Indianapolis City Hall, Nixon and Lugar spoke to the crowd of approximately 1,000 Hoosiers before -

Cold War Rivalry and the Perception of the American West

COLD WAR RIVALRY AND THE PERCEPTION OF THE AMERICAN WEST: WHY BOTH WESTERNERS AND EASTERNERS BECAME COWBOYS AND INDIANS by PAWEL GORAL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2012 Copyright © by Pawel Goral 2012 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members: Drs. Thomas Adam (Chair), Joyce Goldberg, Sam W. Haynes, Meredith McClain, and Steven G. Reinhardt. I would also like to thank other professors who also influenced my work along the way: Eric Bolsterli, Kim Breuer, Stephanie Cole, Imre Demhardt, Marvin Dulaney, Robert Fairbanks, John Garrigus, George Green, Donald Kyle, Stephen Maizlish, Christopher C. Morris, Stanley H. Palmer, Dennis Reinhartz, Stephen Stillwell, Jr. Our departmental staff have been priceless in helping me navigate through the program. I thank Robin Deeslie, Ami Keller, Wanda Stafford, and James Cotton. I thank the staff at the Central Library, especially those in charge of interlibrary loan processing. I thank for the invaluable help I received at the archives at Textarchiv des Deutschen Filminstituts / Deutschen Filmmuseums, Frankfurt, Archiv der Berlin- Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ABBAW), and Bundesarchiv, Berlin. My now three year old daughter, Anna, provided helpful entertainment as I progressed through the writing process. My parents, although thousands of miles away, have stood by me all this time. But the person who made it all possible was my wife, Andrea. I hereby postulate that the spouses of doctoral students should be awarded an iii honorary degree for all the sacrifice it requires to endure. -

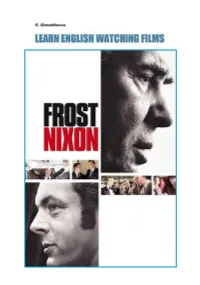

FROST Vs NIXON LEARN ENGLISH WATCHING FILMS Практикум По Английскому Языку

Е.Г. Гиматдинова FROST vs NIXON LEARN ENGLISH WATCHING FILMS Практикум по английскому языку Москва 2019 Факультет журналистики Московского государственного университета имени М. В. Ломоносова Предлагаемая книга является практикумом по английскому языку для аудиторной и самостоятельной работы с художественным фильмом «Фрост против Никсона» режиссѐра Рона Ховарда. Фильм снят в 2008 году по одноимѐнной пьесе Питера Моргана и рассказывает о серии знаменитых телевизионных интервью. Практикум предназначен для студентов факультета журналистики МГУ имени М.В. Ломоносова, а также для широкого круга людей, изучающих английский язык и увлекающихся киноискусством. Материал издания ориентирован на учащихся, владеющих английским языком на уровне B2 - C1 в соответствии с общеевропейской классификацией. Студентам предлагаются лексико-грамматические упражнения и задания, направленные на расширение словарного запаса, развитие и совершенствование навыков аудирования и разговорной речи. Кроме того, практикум содержит статьи, которые знакомят учащихся с героями фильма и историческими событиями, описанными в нем. 3 От автора Предлагаемая книга является практикумом по английскому языку для аудиторной и самостоятельной работы с художественным фильмом «Фрост против Никсона» режиссёра Рона Ховарда. Фильм снят в 2008 году по одноимённой пьесе Питера Моргана и рассказывает о серии знаменитых телевизионных интервью. Практикум предназначен для студентов факультета журналистики МГУ имени М.В. Ломоносова, а также для широкого круга людей, изучающих английский язык и