Screen Sound Journal N5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

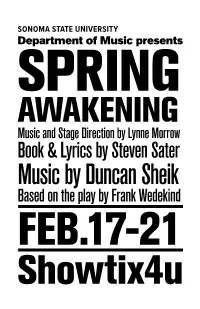

2020 Spring Awakening Program

SONOMA STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Music presents SPRING AWAKENING Music and Stage Direction by Lynne Morrow Book & Lyrics by Steven Sater Music by Duncan Sheik Based on the play by Frank Wedekind FEB.17-21 Showtix4u SPRING AWAKENING Is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supported by MTI. www.MTIShows.com The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Book & Lyrics by Steven Sater Music by Duncan Sheik Based on the play by Frank Wedekind Orchestrations Duncan Sheik Vocal Arrangements AnnMarie Milazzo String Orchestrations Simon Hale Original Broadway Production produced by, IRA PITTELMAN, TOM HULCE, JEFFREY RICHARDS, JERRY FRANKEL, ATLANTIC THEATER COMPANY, Jeffrey Sine, Freddy DeMann, Max Cooper, Mort Swinsky/Cindy and Jay Gutterman/Joe McGinnis/Judith Ann Abrams, ZenDog Productions/CarJac Productions, Aron Bergson Productions/ Jennifer Manocherian/Ted Snowdon, Harold Thau/Terry E. Schnuck/Cold Spring Pro- ductions, Amanda Dubois/Elizabeth Eynon Wetherell, Jennifer Maloney/Tamara Tunie/ Joe Cilibrasi/StyleFour Productions. The world premiere of “SPRING AWAKENING” was produced by the Atlantic Theater Company by special arrangement with Tom Hulce & Ira Pittelman. Artistic TEAMS MUSIC DIRECTOR Lynne Morrow STAGE DIRECTOR Lynne Morrow SET & PROP DESIGN Maliyah Jones (w/Theo Bridant) SCENIC DESIGN ASSISTANTS The Cast with Maliyah Jones COSTUME DESIGN Martha J. Clarke SOUND DESIGN Theo Bridant CHOREOGRAPHER -

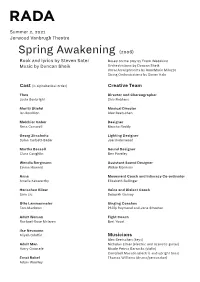

Spring Awakening

Summer 2, 2021 Jerwood Vanbrugh Theatre (2006) Spring Awakening Book and lyrics by Steven Sater Based on the play by Frank Wedekind Music by Duncan Sheik Orchestrations by Duncan Sheik Vocal Arrangements by AnneMarie Milazzo String Orchestrations by Simon Hale Cast (in alphabetical order) Creative Team Thea Director and Choreographer Lucia Bonbright Shiv Rabheru Moritz Stiefel Musical Director Ian Bouillion Alex Beetschen Melchior Gabor Designer Ross Carswell Marsha Roddy Georg Zirschnitz Lighting Designer Dylan Corbett-Bader Joe Underwood Martha Bessell Sound Designer Ciara Coughlin Ben Paveley Wendla Bergmann Assistant Sound Designer Emma Howard Wilkie Morrison Anna Movement Coach and Intimacy Co-ordinator Amelia Kenworthy Elizabeth Ballinger Hanschen Rilow Voice and Dialect Coach Sam Liu Deborah Garvey Otto Lammermeier Singing Coaches Tom Mackean Philip Raymond and Jane Streeton Adult Woman Fight Coach Rachael-Rose Mclaren Bret Yount Ilse Neumann Aliyah Odoffin Musicians Alex Beetschen (keys) Adult Man Nicholas Elmer (electric and acoustic guitar) Harry Omosele Nicole Petrus Barracks (violin) Campbell Masson (electric and upright bass) Ernst Robel Thomas Williams (drums/percussion) Adam Woolley Student Production Team Production Manager Chief Production Sound Scenic Art Head of Department Jemima De Marco Engineer Seda Sokmen Altindag Kieran Dye Technical Manager Scenic Art Assistants Jack Hollingsworth Deputy Chief Production Alice Boxer Sound Engineer India Day Stage Manager James Breedon Aidan O’Sullivan Daisy Jones Sylvia Wan Sound -

SPRING AWAKENING Is Presented by Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

This production contains mature adult content including profanity and violence. It employs the use of chemical fog and includes the smoking of non-tobacco cigarettes. Before the performance begins, please note the exit closest to your seat. Kindly silence your cell phone, pager and other electronic devices. Photography, as well as the videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production, is strictly prohibited. Food and drink are not permitted in the theater. Thank you for your cooperation. SPRING AWAKENING is presented by special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 421 West 54th Street, New York, NY 10019. Phone (212)541.4684. Fax (212)397.4684. www.MTIShows.com. Spring Awakening About the Director Stafford Arima was nominated for an Olivier Award as Best Director for his West End production of Ragtime. He recently directed, Carrie (Off-Broadway), Allegiance (The Old Globe) and Bare (Off-Broadway). Sacramento Music Circus productions include: The King and I, Miss Saigon, Ragtime and A Little Night Music. Other works: Altar Boyz (Off-Broadway); Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris (Stratford Shakespeare Festival), Total Eclipse (Toronto); The Secret Garden (World AIDS Day benefit concert, NYC);The Tin Pan Alley Rag (Off-Broadway); Bowfire (PBS television special); Candide (San Francisco Symphony); A Tribute to Sondheim (Boston Pops); Guys and Dolls (Paper Mill Playhouse); and Bright Lights, Big City (Prince Music Theater, PA). Arima served as associate director for the Broadway productions of Seussical and A Class Act. He studied at York University in Toronto, Canada where he received the Dean’s Prize for Excellence in Creative Work. -

Spring Awakening School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Theatre and Dance Programs Theatre and Dance Fall 2013 Spring Awakening School of Music Illinois State University School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Music and School of Theatre and Dance, "Spring Awakening" (2013). School of Theatre and Dance Programs. 44. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp/44 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Dance at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theatre and Dance Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. steve-o from MTV's Jackass October 5th Donnie Baker & [hick McGee from The Bob & Tom Show October 11th - 12th Ryan Stout from Chelsea Lately ,___.....______ _J October 18th - 19th Al Jackson from Comedy Central October 24th - 26th Adam Ray from the hit movie "The Heat" November 14th - 16th Drew uastines from The Bob and Tom Show November 22nd - 23rd Jamie Kennedy from Malibu's Most Wanted December 5th - 7th 108 E Market Street Bloomington, IL I Phone: 309-287-7698 www.laughbloomington.com ONE WI E ... SCHOOL OF TH 5'l@~ t ::: Illinois5tnw Unii>t,:rity AN~•\ D.fll§ Center for the Performing Arts - Illinois State University September 27 - 28 & October 1 - 5, 7:30 p.m. -

16, 2019 • Merrill Auditorium

PRESENTS MAY 15 - 16, 2019 • MERRILL AUDITORIUM BAKER NEWMAN NOYES AD Best of luck with your 2019 season JS MCCARTHY AD You dream it we print it. jsmccarthy.com 888 465 6241 JSM_Portland Ovation_Neverland Ad.indd 1 4/30/19 10:04 AM NETworks Presentations LLC presents BOOK BY MUSIC AND LYRICS BY James Graham Gary Barlow & Eliot Kennedy Based on the Miramax Motion Picture written by David Magee and the play The Man Who Was Peter Pan by Allan Knee STARRING Jeff Sullivan Ruby Gibbs WITH Conor McGiffin Emmanuelle Zeesman Brody Bett Seth Erdley Caleb Reese Paul Paul Schoeller Josiah Smothers Ethan Stokes AND Emilia Brown Marie Choate Josh Dunn Ashley Edler Joshua William Green Daniel S. Hayward Benjamin Henley Elizabeth Lester Michael Luongo André Malcolm Spenser Micetich Melody Rose Kelsey Seaman Adrien Swenson Josh McWhortor SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER PROJECTION DESIGNER Scott Pask Suttirat Anne Larlarb Kenneth Posner Shannon Slaton Jon Driscoll HAIR & MAKE UP DESIGNER ILLUSIONS AIR SCULPTOR FLYING EFFECTS Bernie Ardia Paul Kieve Daniel Wurtzel Hudson Scenic Studio ORIGINAL MUSIC SUPERVISION VOCAL DESIGNER MUSIC DIRECTOR MUSIC COORDINATOR AND DANCE AND INCIDENTAL MUSICAL ARRANGER AnnMarie Milazzo Patrick Hoagland John Mezzio David Chase ANIMAL DIRECTOR CASTING TOUR BOOKING TOUR PRESS & MARKETING William Berloni Stewart/Whitley The Booking Group Anita Dloniak & Meredith Blair Associates, Inc. GENERAL MANAGER COMPANY MANAGER PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER PRODUCTION MANAGER GENTRY & ASSOCIATES NETWORKS PRESENTATIONS LLC Jamey Jennings Heather Moss David D’Agostino Evan Rooney EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ASSOCIATE CHOREOGRAPHER Trinity Wheeler Camden Loeser ORCHESTRATIONS Simon Hale MUSIC SUPERVISION Fred Lassen CHOREOGRAPHY Mia Michaels DIRECTION RECREATED BY Mia Walker ORIGINAL DIRECTION Diane Paulus Finding Neverland was developed and premiered at The American Repertory Theater at Harvard University, Diane Paulus, Artistic Director, Diane Borger, Producer. -

The Rockstar Newswire

PRECAUTIONS PAN EUROPEAN GAMES INFORMATION (PEGI) AGE RATING SYSTEM • This disc contains software for the PlayStation®3 system. Never use this disc on any other system, as it could damage it. • This disc The PEGI age rating system protects minors from games unsuitable for their particular age group. PLEASE NOTE it is not a guide to gaming conforms to PlayStation®3 specifications for the PAL market only. It cannot be used on other specification versions of PlayStation®3. • Read difficulty. For further information visit www.pegi.info. the PlayStation®3 system Instruction Manual carefully to ensure correct usage. • When inserting this disc in the PlayStation®3 system always Comprising three parts, PEGI allows parents and those purchasing games for children to make an informed choice appropriate to the age of place it with the required playback side facing down. • When handling the disc, do not touch the surface. Hold it by the edge. • Keep the disc the intended player. The first part is an age rating: clean and free of scratches. Should the surface become dirty, wipe it gently with a soft dry cloth. • Do not leave the disc near heat sources or in direct sunlight or excessive moisture. • Do not use an irregularly shaped disc, a cracked or warped disc, or one that has been repaired with adhesives, as it could lead to malfunction. The second part of the rating may consist of one or more descriptors indicating the type of content in the game. Depending on the game, there HEALTH WARNING may be a number of such descriptors. -

Department of Theatre Frank and Joan Dawson DANCING at LUGHNASA by Brian Friel Michael J

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Theatre UAB 2015-2016 Season Department of Theatre Frank and Joan Dawson DANCING AT LUGHNASA by Brian Friel Michael J. and Mary Anne Freeman Directed by Jack Cannon Mary and Kyle Hulcher The Sirote Theatre and October 14 - 17 at 7:30pm & October 18 at 2:00pm l W.B. Philips, Jr. present STUPID F***ING BIRD by Aaron Posner Directed by Dennis McLemon The Odess Theatre November 11 - 14 & 18- 20 at 7 :30pm & November 21 at 2 :00pm BURIED CHILD by Sam Shepard Directed by Karla Koskinen The Sirote Theatre February 24-27 at 7:30pm & February 28 at 2:00pm THEATRE UAB THIRTEENTH ANNUAL FESTIVAL OF TEN MINUTE PLAYS Produced by Lee Shackleford The Odess Theatre March 13 at 2:00pm & March 14 - 17 at 7:30pm SPRING AWAKENING Music by Duncan Sheik. Book & Lyrics by Steven S ater Directed by Valerie Accetta Musical Direction by Carolyn Violi The Sirote Theatre April 13 - 16 at 7:30pm & April 17 at 2:00pm l ASC Box Office: 975-ARTS. Show information at http://www.uab.edu/cas/theatre/productions The Sirote Theatre J in the Alys Robinson Stephens Performing Arts Center OVATION THEARE UAB Theatre UAB Faculty and Administrative Staff (Sponsored by Theatre Advisory Committee) Kelly De an Allison, Professor .................................. ................... .... ..... .. Chair Openin g nights a l Thea tre UAB are OVATION nights. OVATION UAB featu res refr shme nts and conver ation wit h the director and designers before the show, as well a a p L-performance meet & gre the cast· t with and crew. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Lan Xb1 Digital Manual G

WARNUNG Lesen Sie vor dem Spielen dieses Spiels die wichtigen Sicherheits- und Gesundheitsinformationen in den Handbüchern zum Xbox One System sowie in den Handbüchern des verwendeten Zubehörs. www.xbox.com/support. Wichtige Gesundheitsinformationen: Photosensitive Anfälle (Anfälle durch Lichtempfindlichkeit) Bei einer sehr kleinen Anzahl von Personen können bestimmte visuelle Einflüsse (beispielsweise aufflackernde Lichter oder visuelle Muster, wie sie in Videospielen vorkommen) zu photosensitiven Anfällen führen. Diese können auch bei Personen auftreten, in deren Krankheitsgeschichte keine Anzeichen für Epilepsie o. Ä. vorhanden sind, bei denen jedoch ein nicht diagnostizierter medizinischer Sachverhalt vorliegt, der diese so genannten „photosensitiven epileptischen Anfälle“ während der Nutzung von Videospielen hervorrufen kann. Zu den Symptomen gehören Schwindel, Veränderungen der Sehleistung, Zuckungen im Auge oder Gesicht, Zuckungen oder Schüttelbewegungen der Arme und Beine, Orientierungsverlust, Verwirrung oder vorübergehender Bewusstseinsverlust und Bewusstseinsverlust oder Schüttelkrämpfe, die zu Verletzungen durch Hinfallen oder das Stoßen gegen in der Nähe befindliche Gegenstände führen können. Falls beim Spielen ein derartiges Symptom auftritt, müssen Sie das Spiel sofort abbrechen und ärztliche Hilfe anfordern. Eltern sollten ihre Kinder beobachten und diese nach den oben genannten Symptomen fragen. Die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass derartige Anfälle auftreten, ist bei Kindern und Teenagern größer als bei Erwachsenen. Die Gefahr -

To Read the Program Online

The Artistic Director’s Circle Season Sponsors Gail & Ralph Bryan Una K. Davis Brian & Silvija Devine Joan & Irwin Jacobs Sheri L. Jamieson Frank Marshall & Kathy Kennedy Becky Moores Jordan Ressler Charitable Fund of the The William Hall Tippett and Ruth Rathell Tippett Foundation, Jewish Community Foundation David C. Copley Foundation, Mandell Weiss Charitable Trust, Gary & Marlene Cohen, The Rich Family Foundation The Dow Divas, Foster Family Fund of the Jewish Community Foundation, The Fredman Family, Wendy Gillespie & Karen Tanz, Lynn Gorguze & The Honorable Dr. Seuss Fund at The San Diego Scott Peters, Kay & Bill Gurtin, Debby & Hal Jacobs, Lynelle & William Lynch, Foundation and Molli Wagner Steven Strauss & Lise Wilson SEPTEMBER 3 – OCTOBER 13 PRODUCTION SPONSOR Una K. Davis Dear Friends, LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE PRESENTS Christopher Ashley Debby Buchholz There’s a moment in tonight’s musical The Rich Family Artistic Director of La Jolla Playhouse Managing Director of La Jolla Playhouse – don’t worry, no spoilers here – where IN ASSOCIATION WITH a power-mad viceroy, overseeing BERKELEY REPERTORY THEATRE Spain’s colonization of the Americas, MISSION STATEMENT: envisions a glorious future in which most of the towns along the western La Jolla Playhouse advances coast of North America will eventually theatre as an art form and as a vital be named after Catholic saints. San Diego, regardless of the social, moral and political platform thoughts or opinions of our area’s Native population at the by providing unfettered creative time, would indeed become one of those towns; the Spanish opportunities for the leading artists explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo christened it San Miguel in BOOK BY of today and tomorrow. -

Interrogation

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox One system, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. BACKSTORY In the years after World War II, while many struggled to rebuild their lives in a devastated economy, Los Angeles embraced an era of unprecedented growth and prosperity, and Hollywood became a shining beacon of the American Dream to the rest of the world. Yet beneath the glitz and glamour lay a darker reality: a burgeoning drug trade, a movie industry relentlessly preying on naïve young girls, rampant corruption at every level of police and government, and thousands of demobilized troops trying to readjust to civilian life and leave the horrors of war behind them. -

Chaosandcruelty

ERDOGAN’S The showgirl Britain’s ASSAULT ON who married greatest ever THE PRESS Frank Sinatra swimmer BEST EUROPEAN OBITUARIES P43 SPORT P24 ARTICLES P17 5THAUGUST 2017 | ISSUE 1136 | £3.30EWTHE BEST OF THE BRITISHEEK AND INTERNATIONAL MEDIA Chaos and cruelty Inside the court of King Donald Page 4 ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS www.theweek.co.uk There are other ways to travel Transatlantic 4 NEWS The main stories… What happened What the editorials said Any lingering hopes that President Trump “might grow into Trump’s worst week his role as commander-in-chief evaporated this week”, said the A chaotic week in Donald Trump’s White FT – “a chaotic and self-destructive one even House culminated in the firing of both his by the dismal standards of this presidency”. chief of staff, Reince Priebus, and his Trump is “testing the constitutional system to controversial new communications director, destruction”. The president was elected to tear Anthony Scaramucci, a mere ten days after up the Washington rule book, said The Times, his appointment. During an exceptionally “and he is entitled to try”. But he has not turbulent few days, Trump was criticised by managed to advance his agenda, because he Republicans for repeatedly lashing out at his hasn’t convinced Republicans to back it. own attorney general, Jeff Sessions; and by Without discipline this administration will the Pentagon, for announcing a ban on all “fail on the legislative front and may also fail transgender service personnel on Twitter. the most basic test of all – that of survival”.